3.3 The Endomembrane System II — Vesicular Transport and Membrane Fusion

Introduction

As discussed in previous topics, eukaryotic cells contain many distinct membranous compartments. Unique molecules on compartment membranes keep compartments distinct by acting as recognition cues. Trafficking vesicles in animal cells involves moving cargo from packaging and sorting locations in the Golgi body to specific release locations either within or outside the cell. Golgi membrane-bound vesicles use the recognition cues or “coats” to ensure they only fuse with the correct target. This process, known as vesicular trafficking, is highly regulated so that the correct molecules are delivered to their destinations, ensuring the functionality of each intracellular membranous compartment.

This topic will cover the molecular mechanisms involved in vesicle packaging, targeting, budding and fusion.

Unit 3, Topic 3 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 3, Topic 3, you will be able to:

- Describe the origin and paths of intracellular vesicles.

- Summarize and draw the processes of vesicle budding and cargo selection.

- Compare the functions of the various coat proteins involved in vesicle-mediated trafficking.

- Describe the mechanism of clathrin-based, receptor-mediated endocytosis and its relation to human health.

- Describe the mechanism by which secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane.

- Describe the functions of lysosomes and how vesicles are targeted to them.

| Unit 3, Topic 3—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 3, Topic 3 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Coat proteins control the direction of vesicle trafficking. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Vesicle budding of various coat proteins 1. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Clathrin coat formation. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Receptor-mediated endocytosis. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How viruses highjack receptor-mediated endocytosis. | 10 |

| ✮ Complete Learning Activity: Biology of SARS-CoV-2. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Vesicle docking and fusion. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Vesicle budding of various coat proteins 2. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane fusion and neurotransmitter release. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Botulinum B toxin. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Lysosomal targeting. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Protein Trafficking Summary. | 30 |

✮ Important: Please document your work (generate reports, save online work, take pictures and videos, use illustrations, etc.), since you will be asked to present evidence of having done at least one of these activities later on in the course as part of your Unit 3 Assignment.

Vesicles in the Endomembrane System

Path of a Vesicle

In addition to protein processing, the ER and Golgi handle some protein transport types involving vesicles. A vesicle (essentially a membrane-bound bubble) consists of a membrane of phospholipids and cholesterol, first generated in the smooth ER, with a cargo of secretory proteins translated via the RER. Vesicles pinch off from the ER, Golgi, and other membranous organelles, carrying soluble molecules inside the enclosed fluid and any glycosylated molecules embedded in that section of the membrane. These vesicles then catch a ride on a molecular motor (e.g., kinesin or myosin), travel along the cytoskeleton, dock at the appropriate destination, and fuse with the target membrane or organelle. The latter will be the subject of Unit 3, Topic 4.

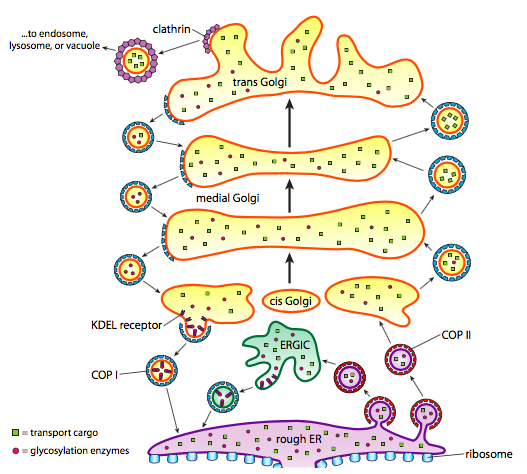

As discussed in the previous topic, vesicles move from the ER to the cis-Golgi, from the cis– to the medial-Golgi, from the medial- to the trans-Golgi, and from the trans-Golgi to the plasma membrane for secretion or to other intracellular compartments. Although most movement occurs in this direction, specific vesicles move back from the Golgi to the ER, carrying proteins that were supposed to stay in the ER (e.g., protein disulfide isomerase and binding immunoglobulin protein) but accidentally end up within a vesicle (Figure 1).

Career Connection: Geneticist

Many diseases arise from genetic mutations that prevent critical proteins from synthesizing. One example is Lowe disease (or oculocerebrorenal syndrome because it affects the eyes, brain, and kidneys), where the Golgi apparatus has an enzyme deficiency. Children with Lowe disease are born with cataracts, typically develop kidney disease after the first year of life, and may have impaired mental abilities.

Lowe disease results from a mutation on the X chromosome. The X chromosome is one of the two human sex chromosomes, as these chromosomes determine a person’s sex. Females possess two X chromosomes, while males possess one X and one Y chromosome. The female body expresses the genes on only one of the two X chromosomes. Females who carry the Lowe disease gene on one of their X chromosomes are carriers and do not show symptoms. However, males only have one X chromosome and the genes on this chromosome are always expressed. Therefore, males will always have Lowe disease if their X chromosome carries the Lowe disease gene. Geneticists have identified the mutated gene’s location and many other mutation locations that cause genetic diseases. Through prenatal testing, a woman can find out if the fetus she is carrying may be afflicted with one of several genetic diseases.

Geneticists analyze prenatal genetic test results and may counsel pregnant women on their options. They may also perform DNA analyses for forensic investigations or conduct genetic research that leads to new drugs or foods.

How Vesicles Form

Vesicles are lipid bilayers organized as spherical droplets that contain substances for shuttling among cellular compartments and secreting into the extracellular space. Vesicle formation depends on coat proteins that will, under proper conditions, assemble into spherical cages. Coat proteins can pull the attached membrane into a spherical shape when associated with transmembrane proteins. The main types of coat proteins used in vesicle formation are the coat protein complex (COP) II, COPI and clathrin. COPII coat proteins form the vesicles that move from ER to the cis-Golgi, called anterograde transport. Anterograde transport is the movement of molecules, organelles, or vesicles toward the cell membrane. COPI coat proteins are used between parts of the Golgi apparatus as well as to form vesicles going from the Golgi back to ERGIC and the ER, called retrograde transport. Retrograde transport is the movement of molecules, organelles, or vesicles away from the cell membrane. Finally, clathrin forms the vesicles, leaving the Golgi for the plasma membrane and the plasma membrane for endocytosis.

COPII, COPI, and clathrin have similar mechanisms for coat protein assembly. A guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) residing on the membrane recruits a small GTPase to the cytosolic face of the lipid bilayer. The inactive GTPase binds to GDP, and the GEF exchanging GDP for GTP activates the GTPase. The active GTPase undergoes a conformation change to reveal an amphiphilic helix that inserts into the lipid bilayer outer leaflet as an anchored foundation for assembling coat and adaptor proteins. The coat proteins induce curvature in the lipid bilayer to form a vesicle and spontaneously (i.e., without any requirement for energy expenditure) self-assemble into cage-like spherical structures around the vesicle. Adaptor proteins bind directly to cargo receptor proteins in the membrane and form the link between the cage and the lipid vesicle. All coat proteins have the common characteristic of the vesicle being held securely within the cage and detaching from the lipid bilayer. One of the proteins bound to the cage structure is a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that causes the small GTPase to hydrolyze the bound GTP into GDP. GTP hydrolysis destabilizes the cage. The vesicle uncoats as the cage disintegrates. Residual proteins bound to the vesicle identify and dock with the destination membrane as the vesicle moves in the cytosol.

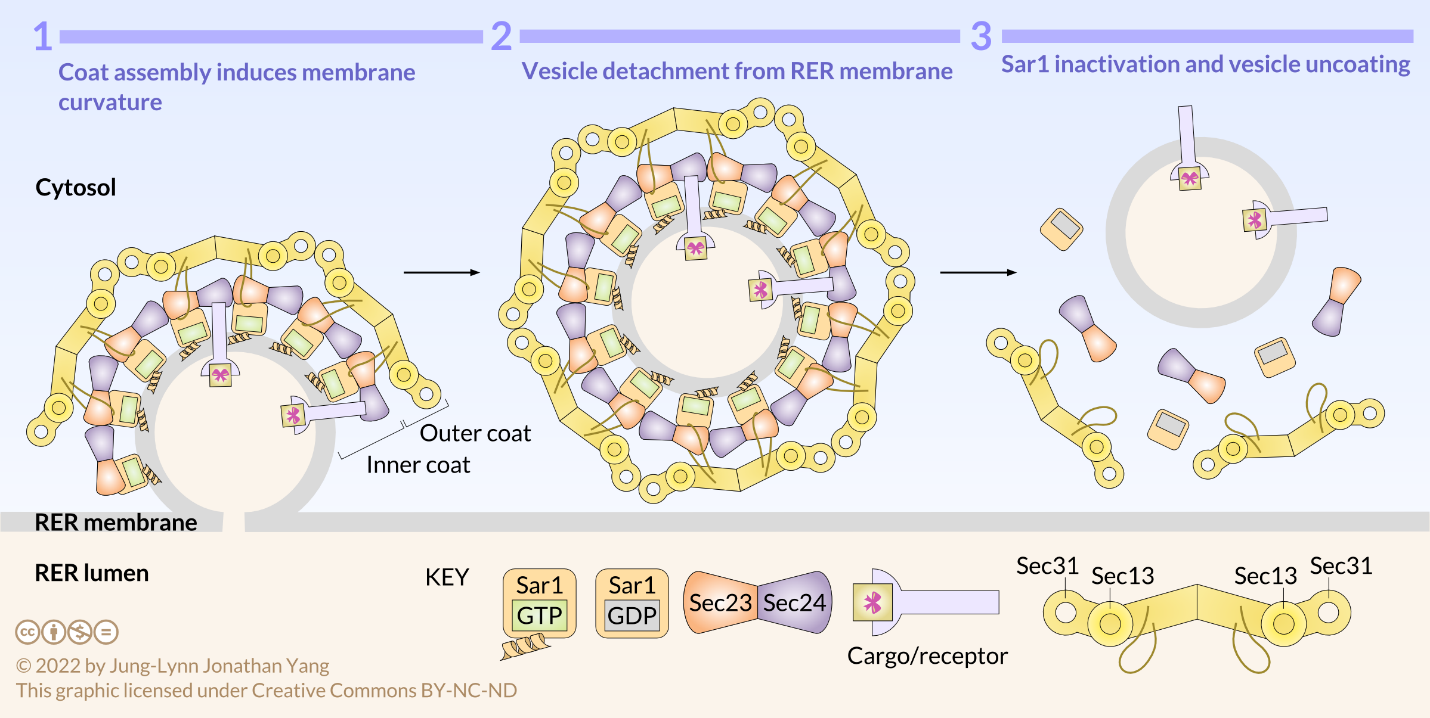

COPII-coated vesicles carry molecules in an anterograde direction from the RER to the ERGIC, if present, and to the cis-Golgi. Vesicle assembly occurs in specialized zones of the RER called ER exit sites. Sec12, the RER-resident GEF, activates Sar1 GTPase by guanine nucleotide exchange (Figure 2). The conformationally active Sar1 anchors into the RER membrane by an amphiphilic helix and recruits heterodimers of Sec23 and Sec24 as the adaptors that form the inner coat of COPII. Sec23 binds to Sar1, and Sec24 binds to ER exit amino acid sequences in the cytosolic tails of membrane-bound cargo proteins. Receptors in the RER membrane sequester soluble cargo proteins in the RER lumen. The cytosolic tails of these receptors bind to Sec24, thereby packaging soluble cargo into export vesicles. Moreover, Sec23 recruits heterotetramers of Sec13 and Sec31 that form the outer coat and the characteristic polyhedral cage of COPII-coated vesicles. The polymerization of adaptor and coat proteins forces the lipid bilayer into a spherical structure that detaches from the RER membrane. Sec23 is also the GAP that causes Sar1 to hydrolyze the bound GTP to GDP and the vesicle to uncoat. Hydrolysis of the GTP on Sar1 appears to weaken the coat protein affinity for the adaptors.

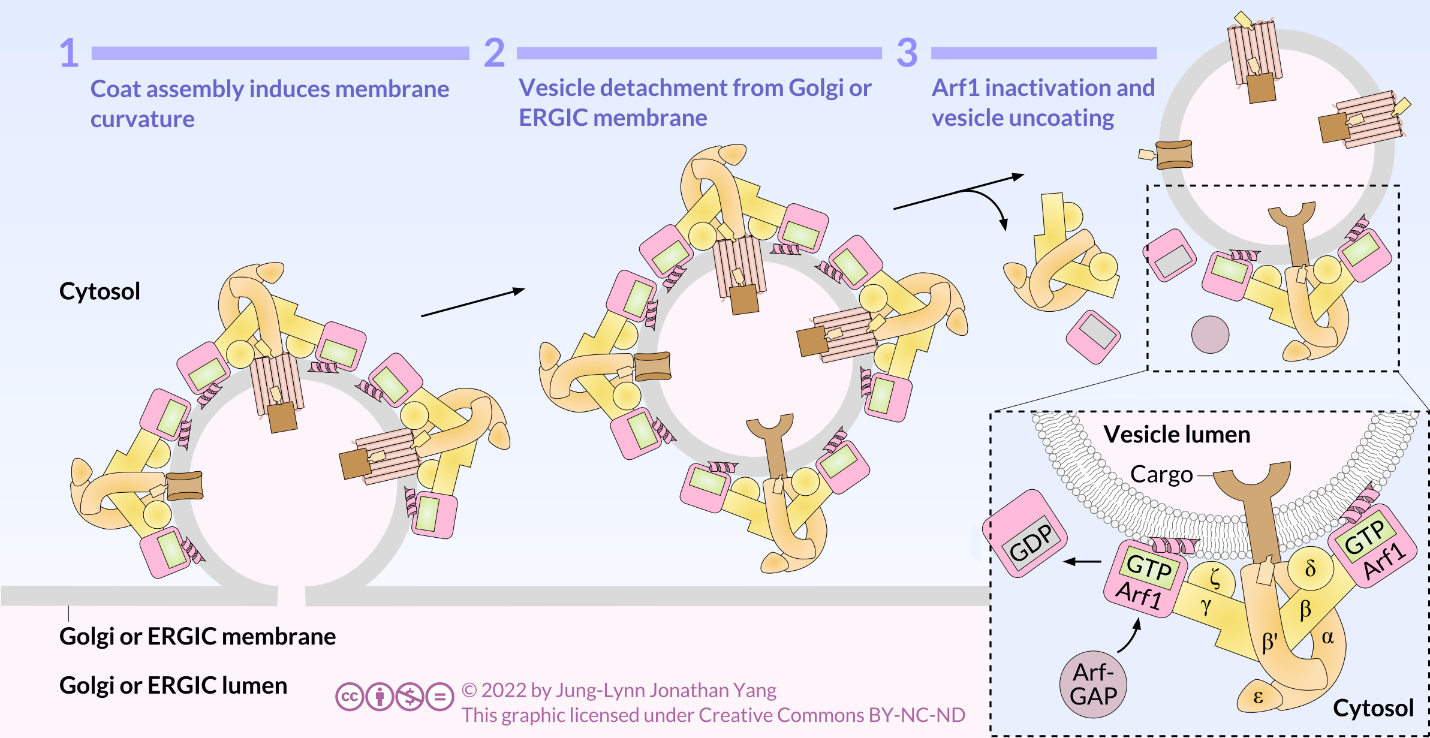

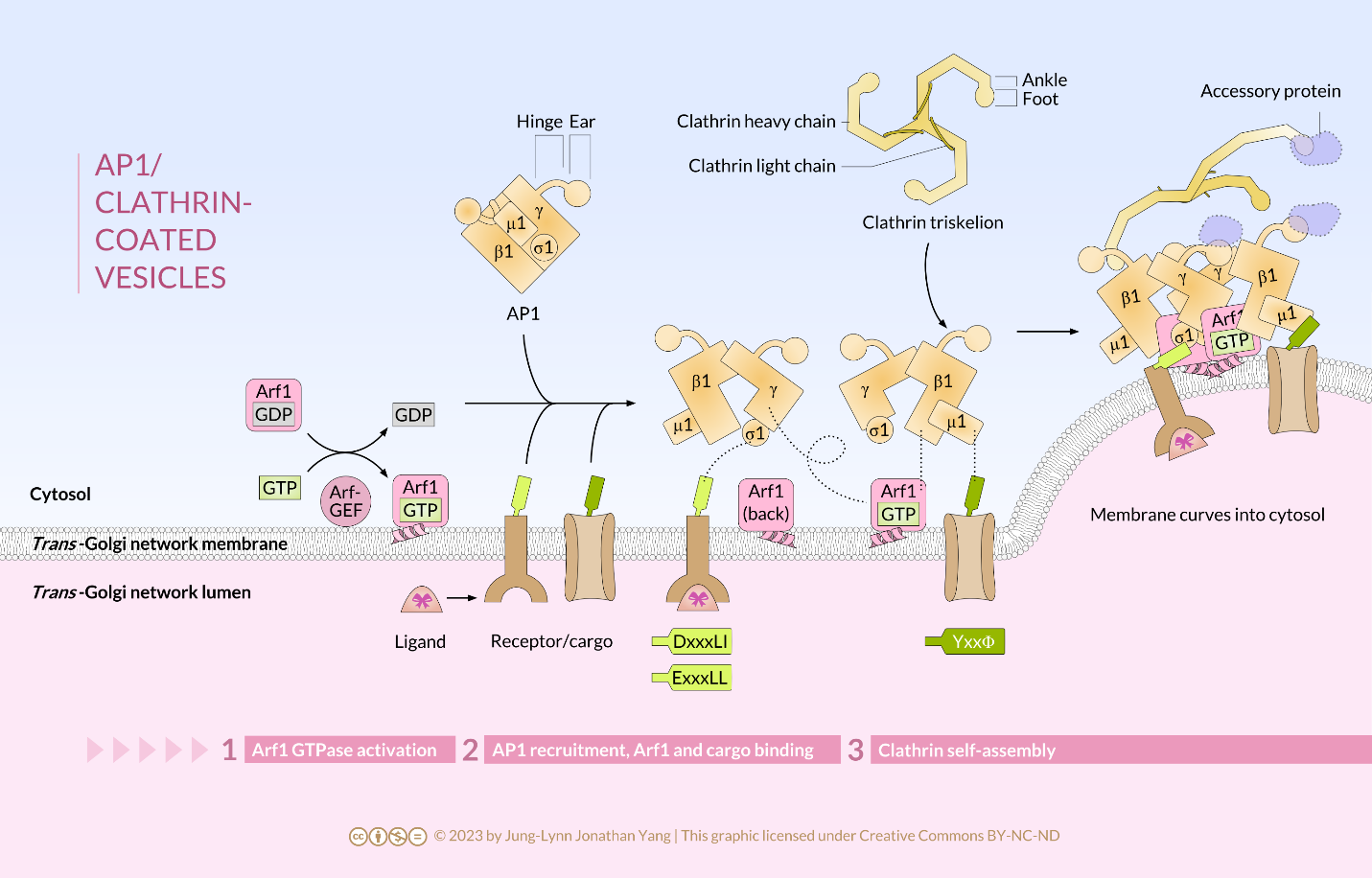

COPI-coated vesicles are responsible for retrograde transport from the Golgi to the RER and among Golgi cisternae. Retrograde transport retrieves substances, such as resident proteins of the RER and specific Golgi cisterna, caught in anterograde vesicles and moved into an inappropriate cellular compartment. COPI assembly begins by recruiting ARF1 (ARF stands for ADP ribosylation factor, which has nothing to do with its function here) to the membrane (Figure 3). This recruitment requires an ARF nucleotide binding site opener (ARNO) to facilitate the exchange of a GTP for the GDP bound by ARF1. Once ARF1 has bound GTP, the conformational change reveals an N-terminal myristoyl group that inserts into the membrane. COPI adaptor (F-subcomplex) consists of the coat promoter (coatomer) subunits β-, γ-, δ-, and ζ- COP. The α-, β′-, and ε-COP coatomer subunits form the outer layer of COPI, the B- subcomplex. Cargo is bound to α- and β′-COP and ARF1 is bound to β- and γ-COP. A triad forms from the heptamer of coatomers. This triad is the repeating unit that forms the cage around the vesicle. ARF-GAP regulates GTP hydrolysis by ARF1. GDP-bound ARF1 dissociates from the surface of the vesicle along with the coatomers, and the vesicle uncoats.

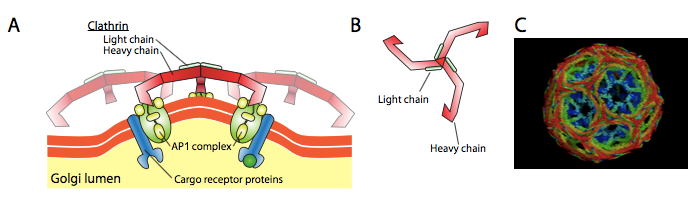

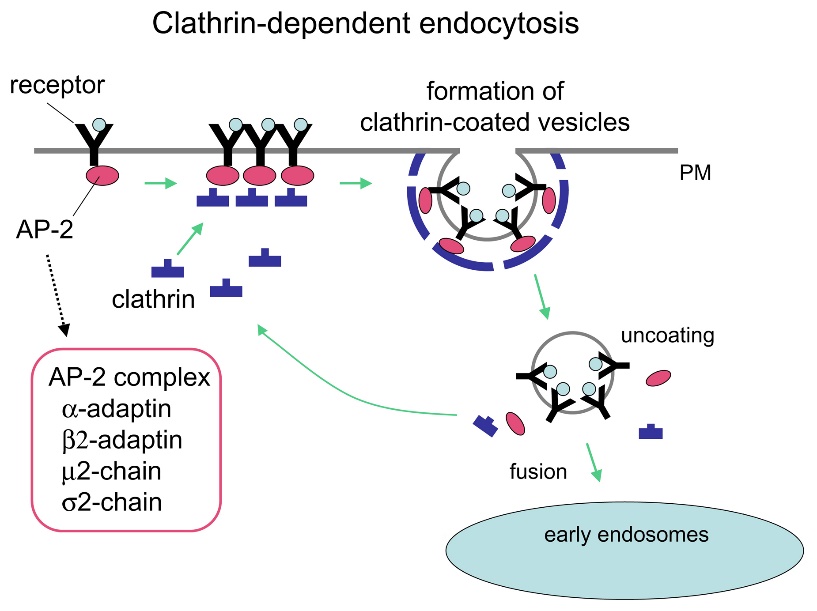

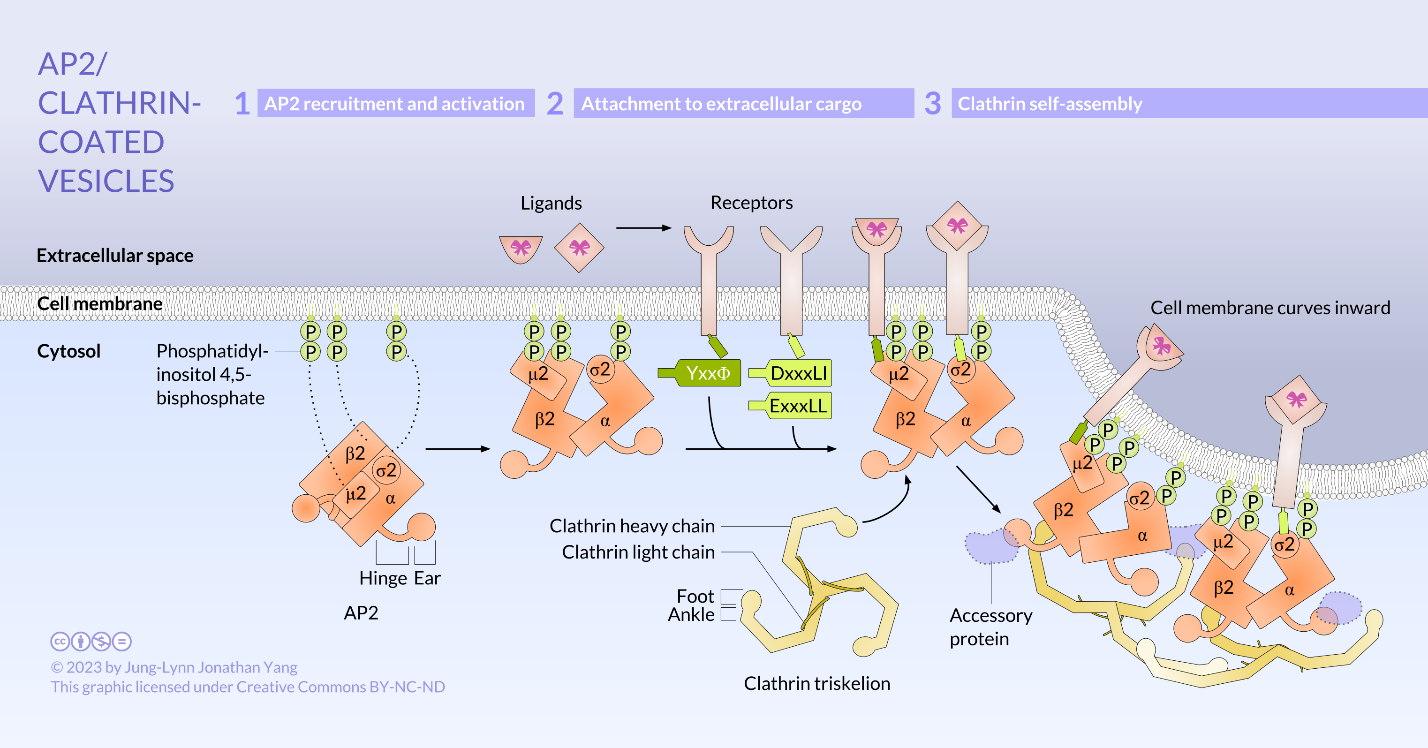

Clathrin is the best described of the three coat proteins, and the arrangement of clathrin triskelions (from Greek, meaning three-legged) generates the vesicular coats (Figure 4). Each triskelion consists of three heavy chains joined at the C-terminus and three light chains, one associated with each heavy chain. The heavy chains of different triskelions interact along the length of their heavy chain “legs” to create a very sturdy construct. The light chains are unnecessary for vesicle formation but may help prevent accidental interactions of clathrin molecules in the cytoplasm. The adaptor protein complexes consist of two large adaptin subunits, a medium subunit μ, and a small subunit σ and act as the link between the membrane (through the receptors) and the coat proteins. Clathrin-coated vesicles transport molecules from the trans-Golgi to endosomes; they also transport molecules from the plasma membrane so they can undergo exocytosis. Endocytic vesicles that carry extracellular substances into cells are also clathrin-coated. The difference among these clathrin-coated vesicles is in the composition of the adaptor protein (AP) complexes: AP2 for endocytic vesicles (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and AP1 for trans-Golgi-derived vesicles (Figure 7). The hexagonal and pentagonal shapes bounded by the clathrin subunits give the vesicle a “soccer ball” look. In contrast, COP coatomer-coated vesicles appear much fuzzier under the electron microscope.

Learning Activity: Coat Proteins Control the Direction of Vesicle Trafficking

- Use the information in your Unit 3, Topic 3 readings to fill in the following table. Include the general term for the direction of each vesicle movement.

- Draw your own figure showing the information summarized in your table and label each component from the nucleus to the plasma membrane. Label each vesicle with the correct coat protein.

You may download the table to fill in by hand or electronically.

|

Coat protein |

Direction of vesicle movement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learning Activity: Vesicle Budding of Various Coat Proteins 1

- Watch the video “Vesicle Budding (Vesicle Transport and Formation)” (6:00 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2019).

- Answer the following questions:

- When does Sar1-GTP act during vesicle budding, and what does it do? What causes coat disassembly?

- When does ARF1 act during vesicle budding, and what does it do? What causes coat disassembly?

Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis

The major endocytosis route in most cells, and the best understood, is the one mediated by clathrin. Receptor-mediated endocytosis, also called clathrin-mediated endocytosis, is a process by which cells absorb metabolites, hormones, and proteins (and, in some cases, viruses) through the inward budding (invagination) of the plasma membrane. This process forms vesicles containing the absorbed substances. Receptors on the surface of the cell strictly mediated it. Recall from Unit 2, Topic 3 that only receptor-specific substances can enter the cell through this process (Figure 5).

As vesicular traffic occurs towards the plasma membrane, either for secretion or incorporation of membrane lipids or proteins, vesicular traffic also occurs from the plasma membrane. Endocytosis is the process by which a coat protein, usually clathrin, on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane, begins to polymerize a coat that draws the membrane with it into a vesicle containing material from outside of the cell. Sometimes, endocytosis initiates internally, such as to remove a particular protein from the cell surface (e.g., trailing edge dynamics in cell motility). Other times, endocytosis results from a cell surface receptor binding a ligand from the external environment, leading to receptor activation and subsequent nucleation of clathrin assembly and vesicle formation.

Click on the images to download the full-size infographics about the assembly of clathrin-coated vesicles at the cell membrane (Figure 6) andat the trans-Golgi membrane (Figure 7).

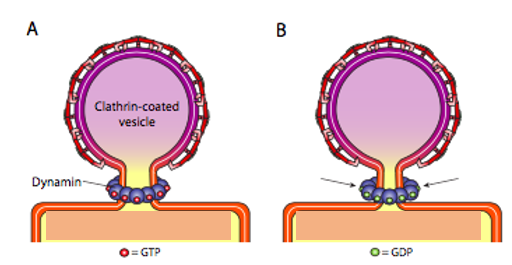

First, extracellular cargo molecules bind to a specific membrane-bound receptor on the cell surface. The AP2 adaptin subunits bind to the intracellular end of membrane-bound receptor proteins, acting as the link between the membrane (through the receptors) and the clathrin coat proteins (Figure 5). Then, clathrin attaches to the adaptin proteins where they spontaneously (i.e., without any requirement for energy expenditure) self-assemble into cage-like spherical structures (Figure 4C). Clathrin-coated invaginations are known as “coated pits.” Next, the plasma membrane containing receptors undergoes inward budding to turn into clathrin-coated vesicles. Finally, the dynamin protein pinches off the membrane (Figure 8), releasing the coated vesicle into the cytoplasm. Dynamin molecules are globular GTPases that contract upon GTP hydrolysis. When associated around the vesicle stalk, the combined effect of each dynamin protein contracting constricts the stalk enough that the membrane pinches together, sealing off and releasing the vesicle from the originating membrane. The coat proteins come off shortly after vesicular release in the cytoplasm. For clathrin, the uncoating process involves the ATPase Hsc70.

Learning Activity: Clathrin Coat Formation

- Watch the video “Clathrin Full Rendering” (2:20 min) by Biology Help (2017).

- Answer the following questions:

- What cellular structure is the dark black line observed in the transmission electron micrograph of the coated pit forming at the beginning of this video? This sample was stained with osmium tetroxide. Why is it dark (recall Unit 1, Topic 3)?

- What is the name of the proteins that connect the receptors with the clathrin coat?

- What is the name of the shape formed by individual clathrin molecules in an electron microscope? How many chains does it have? What domains bind to adaptins?

- How do numerous clathrin proteins come together?

Clathrin-Based, Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis of the Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Receptor

Cholesterol is an essential component of all cell membranes. Human cells get much of their cholesterol from the liver and, assuming your diet is not strictly “100% cholesterol-free,” by absorption from the intestine. Most cells can, as needed, either synthesize cholesterol or acquire it from the extracellular fluid using receptor-mediated endocytosis. There are many types of ligands in addition to cholesterol: a nutrient molecule (usually on a carrier protein, as in the examples below) or even an attacking virus which has co-opted the endocytic mechanism to facilitate entry into the cell. The example depicted here is a classic example: cholesterol endocytosis via low-density lipoprotein (LDL). This example illustrates one potential pathway the receptors and their cargo may take.

Cholesterol is a hydrophobic molecule that is pretty insoluble in water. Thus, it cannot pass on its own from the liver and/or the intestine to the cells dissolved in blood and extracellular fluid. Instead, a lipoprotein transports it. The most abundant cholesterol carriers in humans are the LDLs.

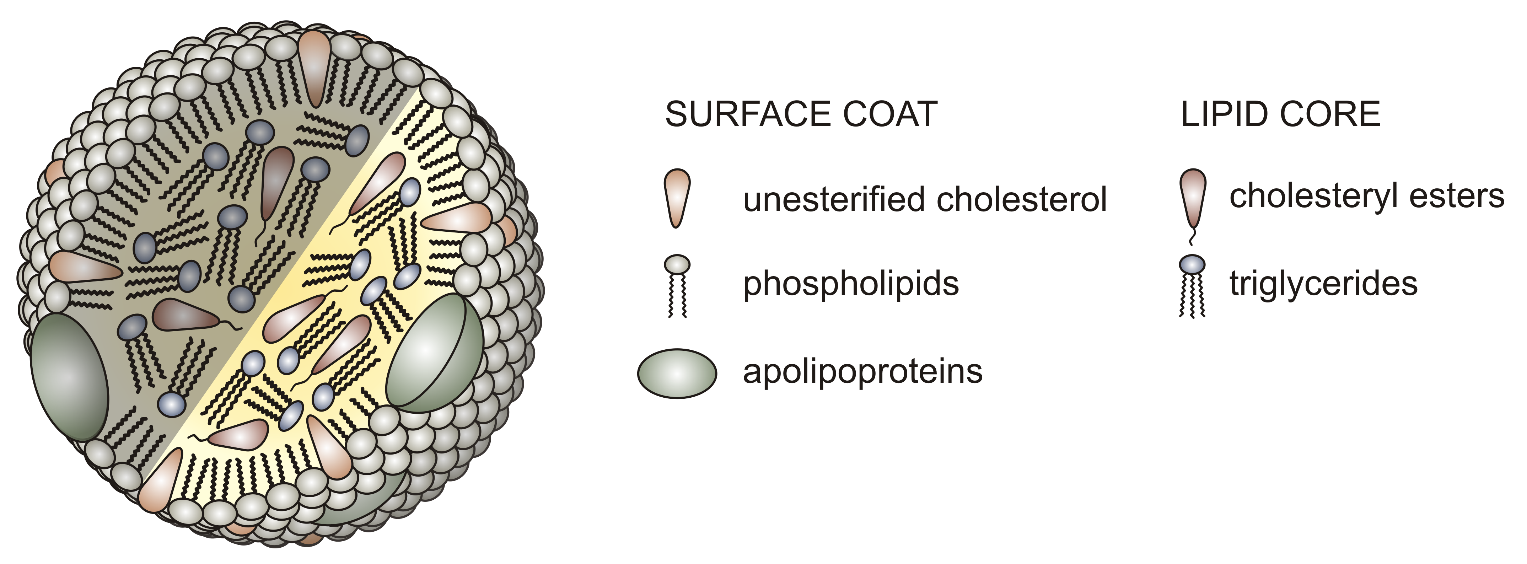

LDL particles are spheres covered with a single phospholipid layer, with hydrophilic heads exposed to the watery fluid (e.g., blood) and hydrophobic tails directed into the interior. Some 1,500 molecules of cholesterol (each bound to a fatty acid) occupy the hydrophobic interior of LDL particles. Each LDL particle has one protein molecule called apolipoprotein B exposed at its surface (Figure 9).

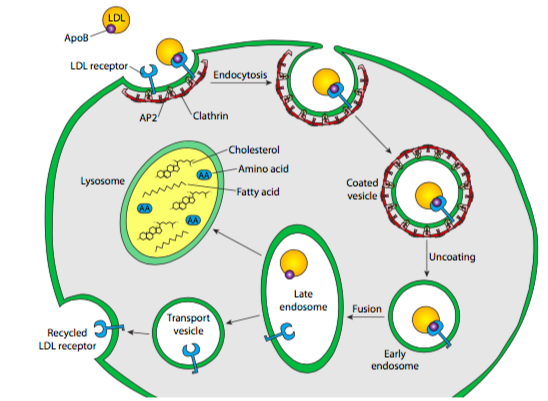

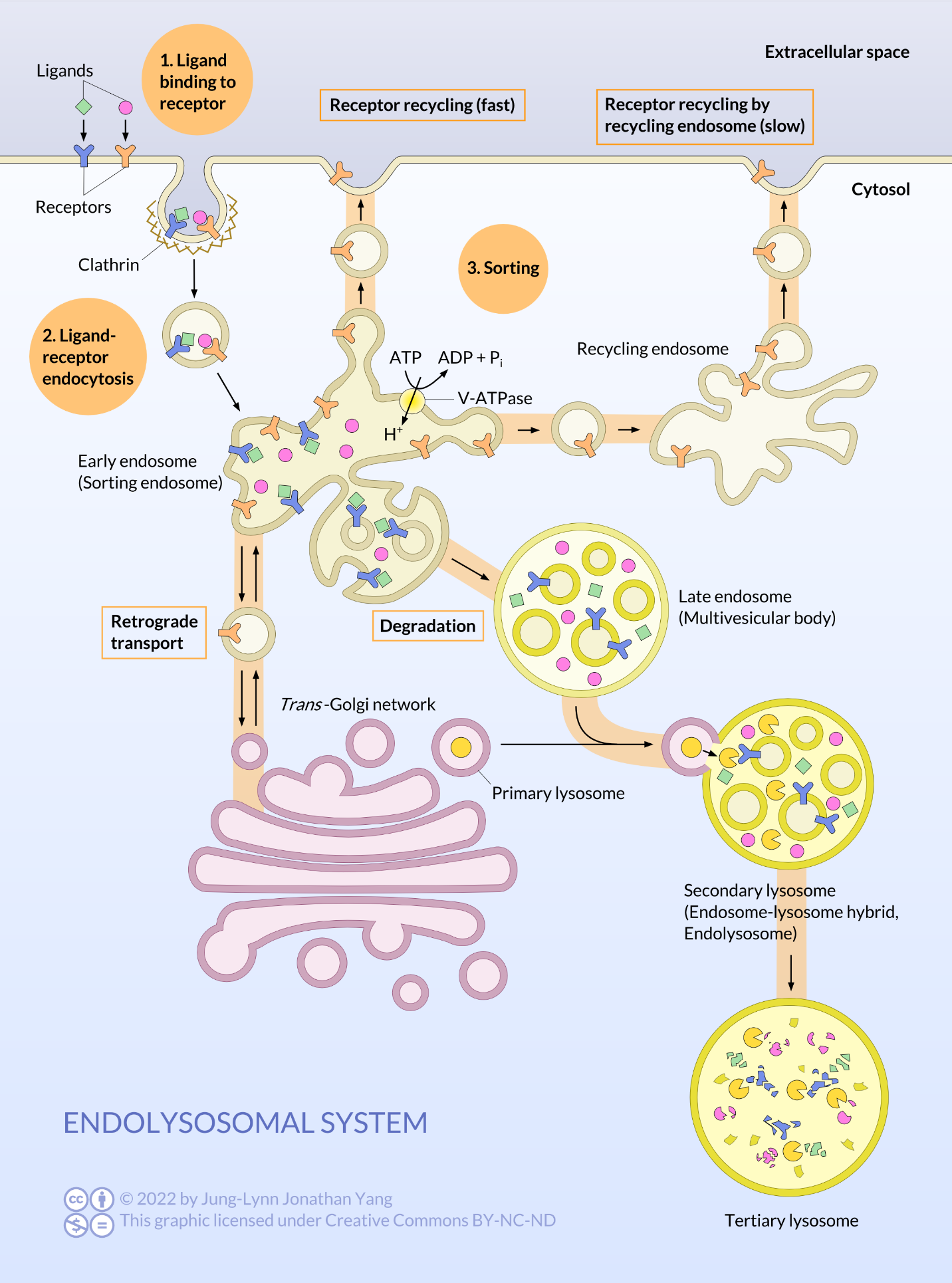

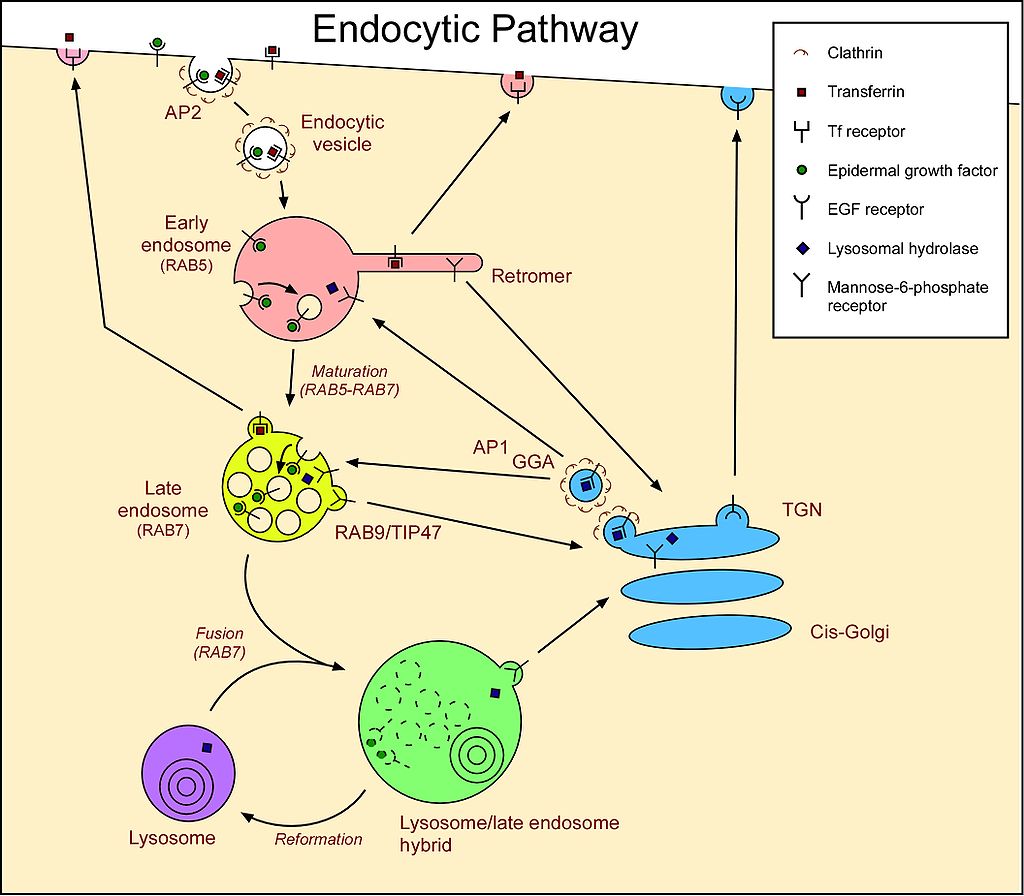

Cells acquire LDL particles by first binding them noncovalently to LDL receptors exposed at the cell surface. These transmembrane proteins have a site that recognises and binds to the apolipoprotein B on the surface of the LDL. LDL receptors tend to aggregate in clathrin-coated pits that already have a small number of polymerized clathrin molecules. The portion of the plasma membrane with bound LDL uses endocytosis to internalize the vesicle via a clathrin-dependent process. The vesicle forms as described previously for Golgi-derived clathrin vesicles: the clathrin self-assembles into a spherical vesicle, and dynamin pinches the vesicle off the cell membrane. This is the beginning of the endocytic pathway of vesicles. Internalized material from endocytosis passes through a structure called an endosome. The exception is material engulfed via phagocytosis, which only the lysosome processes. Endosomes are membrane-bound structures inside eukaryotic cells that play a role in endocytosis. They have a sorting function for material internalized into the cell, providing a spot to retrieve materials not destined to be destroyed in the lysosomes. For example, LDL molecules are targeted after endocytosis to the endosomes for processing before part of them is delivered to the lysosome.

In the early endosome, a pump moves H+ into the endosome against the concentration gradient. Endosomal proton pumps are ATP-driven, Mg2+-V-type pumps (as opposed to F-type pumps in the mitochondrial inner membrane). The increase in H+ reduces the pH (~pH 7.0 to pH 5.0) in the early endosome, which breaks the noncovalent bonds between the LDL cargo and the receptor. The early endosome then pinches apart into two smaller vesicles: one containing free LDL cargo molecules and the other now-empty receptors. The vesicle with the LDL cargo fuses with a primary lysosome to form a secondary lysosome. A hydrogen ion pump in the lysosome membrane decreases the pH even further (~pH 2.0-3.0). Then, enzymes in the lysosome release free cholesterol into the cytosol. The vesicle with unoccupied receptors returns to and fuses with the plasma membrane, turning inside out as it does so (exocytosis). In this way, recycling LDL receptors to the cell surface allows for reuse (Figure 10).

People who inherit two defective (mutant) genes for the LDL receptor have receptors that function poorly or not at all. This dysfunction creates excessively high LDL levels in their blood and predisposes them to atherosclerosis and heart attacks. Hypercholesterolemia is inherited. Mutations in the apolipoprotein B gene cause another form of inherited hypercholesterolemia.

Learning Activity: Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

- Watch the video “Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis Overview (Process of Endocytosis and Maturation of Endosomes)” (6:00 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2019).

- Answer the following questions:

- List the four steps in receptor-mediated endocytosis.

- Where do endocytic vesicles form in the membrane?

- What marks the beginning of vesicle formation?

- What causes the vesicle to pinch off the membrane?

- With what structure do all incoming vesicles fuse? What are two destinations for endocytosed materials?

- What happens in early endosomes?

- What is the next destination of cargo in the early endosome?

- What protects the endosome membrane from lysosomal enzyme degradation?

- What is the last destination of the late endosome? What is the end product?

Learning Activity: How Viruses Highjack Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

The following simulation demonstrates how the SARS-CoV-2 virus infects cells and how this response differs in the presence or absence of vaccination.

- Go to the LabXchange simulation “COVID infection with and without vaccination” by BioDigital (2020).

- Click on ‘Start interactive’ and give the interactive time to load. Please note that there is a speaker with which you can play audio on the top left of the image.

- Read through page 1 on COVID-19 infection without vaccination.

- Click on each element noted with a plus sign.

- Make your own notes.

- Click the arrow at the bottom of the screen to advance to page 2 on the immune response.

- Click on each element noted with a plus sign.

- Scroll in with your mouse to get a close-up view.

- Click on the explore arrow to investigate each element of the virus.

- Click isolate to see each structure.

- Make your own notes.

- Repeat c to e with the ACE-2 membrane receptor.

✮Learning Activity: Biology of SARS-CoV-2

This series explores the biology of the virus SARS‑CoV‑2, which has caused a global pandemic of the disease.

COVID‑19. SARS‑CoV‑2 is part of a family of viruses called coronaviruses. The animations describe the structure of coronaviruses like SARS‑CoV‑2, how they infect humans and replicate inside cells, how the viruses evolve, methods used to detect active and past SARS‑CoV‑2 infections, and how different types of vaccinations for SARS‑CoV‑2 prevent disease.

- Go to the “Biology of SARS-CoV-2” interactive website by BioInteractive (2021) and scroll through the four-part animation series.

- Select the “Start” button to view the first animation, or use the navigation menu on the top to select one of the four animations: Infection, Evolution, Detection, and Vaccination. These animations are also a great introduction to antigens and antibodies. Please make notes, as you need a portion of this information to complete the Unit 3 Assignment.

Vesicle Fusion and Cargo Release

Vesicles carry two types of cargo: soluble proteins and transmembrane proteins. Vesicles take up some soluble proteins when they bind to a receptor. Other proteins that happen to be in the vicinity get scooped up as the vesicle forms. Occasionally, a vesicle takes up a protein that was not supposed to be. For example, protein disulfide isomerase or binding immunoglobulin protein may become enclosed in a vesicle forming from the RER; it has little function in the Golgi, and the RER needs it, so what happens to it? Fortunately, protein disulfide isomerase, binding immunoglobulin protein, and many other RER proteins have a C-terminal signal sequence, KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu), that screams, “I belong in the ER.” KDEL receptors inside the Golgi recognise these sequences, and KDEL proteins binding to the receptors trigger COPI vesicle formation to send them back to the RER. KDEL is known as a retrieval tag and is one of the cell’s many backup mechanisms.

Secretory vesicles have a specific problem with soluble cargo. If the vesicle relies on enclosing proteins within it during the formation process, achieving high concentrations of those proteins would be difficult. The organism needs many secreted proteins quickly and in significant amounts, so there is a mechanism in the trans-Golgi for aggregating secretory proteins. The mechanism uses aggregating proteins (e.g., secretogranin II and chromogranin B) to assemble target proteins in large, concentrated granules. These granins work best in the trans-Golgi milieu of low pH and high [Ca2+], so when the vesicle releases its contents outside of the cell, the higher pH and lower [Ca2+] break apart the aggregates to release the individual proteins. A consistent pH change occurs during Golgi maturation, resulting in each compartment going from the RER to the Golgi having a progressively lower, more acidic luminal pH.

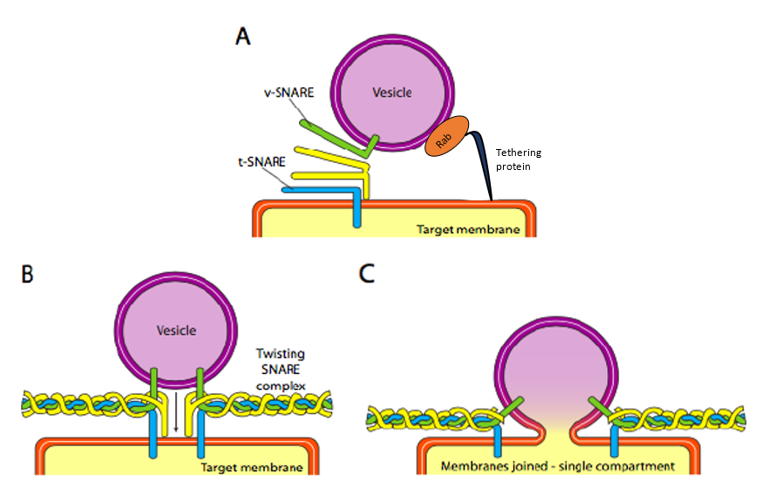

Finally, the vesicles need targeting. The vesicles are much less helpful when tossed on a molecular freight train and dropped off at a random station. Therefore, specific protein interactions need to happen for vesicle contents to be delivered, also called vesicle fusion. Vesicle docking and fusion require two sets of proteins: Rab-GTP on the vesicle surface and tethering proteins on the target membrane. Additionally, the vesicle fusion requires matching the v-SNARE protein on the vesicle’s surface and the t-SNARE on the surface of the target membrane. SNARE stands for soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor. The tethering proteins, which initially contact an incoming vesicle by interacting with Rab-GTP, will draw the vesicle close enough to the target membrane to test for SNARE protein interaction. More specifically, as a vesicle approaches the target membrane, the tethering protein (linked to the target membrane) loosely associates with the vesicle by binding Rab-GTP and holds it in the vicinity of the target membrane to give the SNARES a chance to bind to each other. The v-SNAREs and t-SNAREs can now interact and test for a match (Figure 11).

Vesicle fusion to the membrane only proceeds if there is a match. Otherwise, the vesicle cannot fuse and will attach to another molecular motor to head to another, hopefully correct, destination. Other proteins on the vesicle and target membranes then interact, and if the SNAREs match, it can help to “winch” the vesicle into the target membrane. Then, the membranes fuse. In membrane fusion, the v-SNAREs of a secretory vesicle (upper left) interact with two t-SNAREs of a target membrane (Figure 11A). The v- and t-SNAREs “zipper” themselves together to bring the membrane vesicle and the target membrane closer together (Figures 11B and 11C).

Zippering also causes flattening and lateral tension in the curved membrane surfaces, favouring hemifusion in the outer layers of each membrane. Continued tension results in subsequent fusion of the inner membranes, causing the vesicle chamber to open its contents to its target (usually outside the cell). Eventually, the hexameric ATPase (of the AAA type) called N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) catalyzes the ATP-dependent unfolding of the SNARE proteins and releases them into the cytosol for recycling.

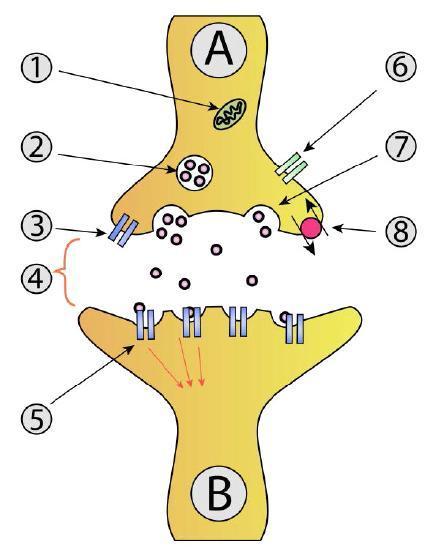

The SNARE pathway in neurotransmitter release involves vesicles filled with neurotransmitters. Motor proteins position these vesicles at the axon terminals. The process where secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane at only one end of a cell is known as polarized secretion. Once an action potential is received, the vesicle fuses using SNARE proteins to release the neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. This part happens upon the influx of calcium into the axon terminus (Figure 12).

Learning Activity: Vesicle Docking and Fusion

- Watch the video “Vesicle Fusion (Membrane Docking and Cargo Release)” (5:05 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2019).

- Answer the following questions:

- Which GTPase plays a role in docking and vesicle fusion?

- How does this GTPase help in vesicle docking? What is vesicle docking?

- Which proteins provide further target specificity and fusion?

- What is the rate-limiting step of vesicle fusion?

- How are Rab-GTPs released from the target membrane?

- How do the v-SNAREs and t-SNAREs become untangled from the membrane after the vesicle fuses and cargo releases into the cell? What happens to them?

Learning Activity: Vesicle Budding of Various Coat Proteins 2 (Draw It to Know It!)

- Watch the video “Cell and Molecular Biology: Vesicular Budding and Fusion” (7:40 min) by Ditki – Medical & Biological Sciences (2016). Make your own notes.

- Draw the process by following the instructions in this tutorial. Compare these to your answers in the previous Unit 3, Topic 3 Learning Activity Coat proteins control the direction of vesicle trafficking.

Interruption of Vesicle Fusion

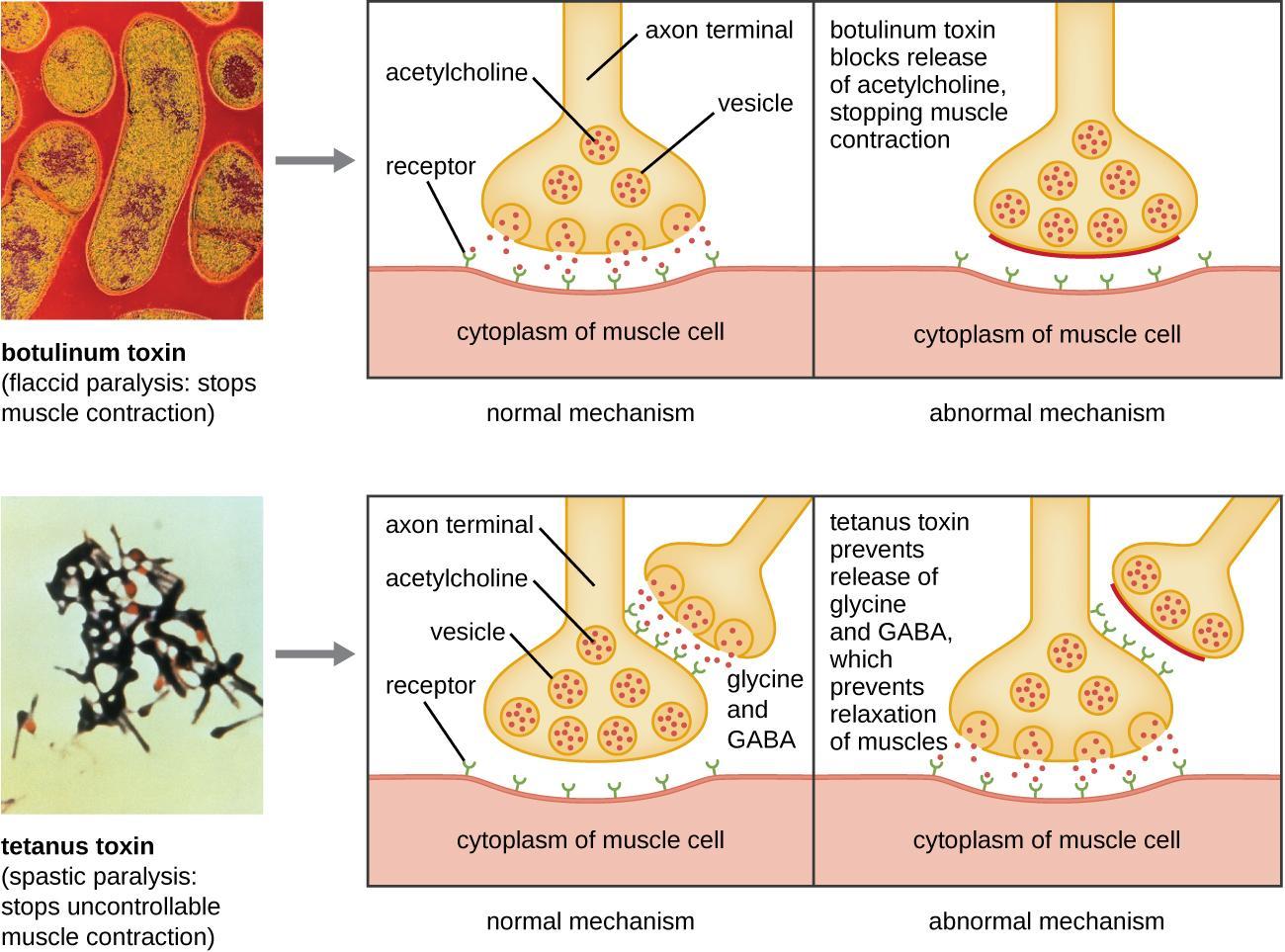

Some toxins have been shown to act directly on the pathway of vesicle fusion. For example, the tetanus toxin, tetanospasmin, released by Clostridium tetani bacteria, causes spasms by acting on nerve cells and preventing neurotransmitter release. Tetanus toxin cleaves synaptobrevin (a SNARE protein), so synaptic vesicles cannot fuse with the cell membrane. Interneurons usually release the inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) that signal neurons at neuromuscular junctions to downregulate acetylcholine release. Tetanus toxin stops this release of glycine and GABA, resulting in permanent muscle contraction. The first symptom is typically stiffness in the jaw (lockjaw). Violent muscle spasms in other parts of the body follow, typically culminating in respiratory failure and death.

Botulinum toxin, from Clostridium botulinum, also acts on SNAREs to prevent vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release. However, it targets different neurons than tetanus toxin, resulting in the opposite effect: tetanus is caused by preventing the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, while botulism is by preventing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters (Figure 13).

Botulinum toxin, one form sold under the brand name BOTOX, can be used to treat several disorders involving excessive muscle contraction, including migraines and cervical dystonia. Cervical dystonia causes abnormal, involuntary muscle contractions of the neck. This results in jerky head and neck movements and/or a sustained abnormal tilt of the head. It is often painful and can significantly interfere with a person’s life. For cosmetic purposes, botulinum toxin can be injected into the facial muscles to relax them, reducing the appearance of wrinkles. When used to treat cervical dystonia, it is injected into the neck muscles to inhibit excessive muscle contractions. Botulinum toxin does this by cleaving SNARE proteins to prevent neurotransmitters from being released. For many patients, this injection helps relieve the abnormal positioning, movements, and pain associated with the disorder. However, the effect is temporary. Patients must repeat injections every three to four months to keep the symptoms under control.

Learning Activity: Membrane Fusion and Neurotransmitter Release

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Neurotransmitter Release” (2:00 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2018).

- Answer the following questions:

- How do neurotransmitters get transferred from the pre-synaptic to the post-synaptic membrane?

- Describe the events that activate vesicle movement and the molecules involved until neurotransmitter release in the synaptic cleft.

Learning Activity: Botulinum B Toxin

- Watch the video “BOTOX Mechanism of Action – JS Muscle Science” (1:33 min) by JS Muscle Science (2020).

- Answer the following questions:

- Why is acetylcholine not released into the synaptic cleft upon BOTOX injection?

- How does this prevent wrinkles?

Vesicle Targeting to Lysosomes

Vesicles containing substances taken up by receptor-mediated endocytosis first undergo sorting at the early endosome (Figure 14). The acidic environment in the early endosome dissociates ligands from their receptors. The unoccupied receptors may be sorted quickly back to the cell surface or, more slowly, via a recycling endosome. Unoccupied receptors may also move toward the Golgi apparatus. Ligands and other receptors get packaged into a late endosome, which is a large vesicle with many small vesicles inside. The late endosome fuses with a primary lysosome to digest the endosomal contents.

Lysosomes are roughly spherical organelles enclosed by a single membrane. The Golgi apparatus manufactures them as a primary lysosome, which can fuse with a late endosome to form either a secondary lysosome or endolysosome. Lysosomes contain over 50 different hydrolytic enzymes, including proteases, lipases, nucleases, and polysaccharidases. All enzymes in the lysosome are collectively known as acid hydrolases because they work best at an acidic pH. This pH reduces the risk of them digesting their own cell should they escape from the lysosome. The pH within the secondary lysosome is about pH 5.0, substantially less than that of the cytosol (~pH 7.2). In addition to having proton pumps to acidify the internal environment, the lysosomal membrane incorporates many transporter proteins to aid in moving products digested by acid hydrolases out of the lysosome so that the cell can make use of the resulting amino acids, sugars, nucleotides, and lipids. Interestingly, lysosomal proteases do not digest these transporter proteins because heavy glycosylation shields potential proteolytic sites from the proteases.

Self-Check

Why do lysosomes not digest themselves?

Show/Hide answer.

Most proteins found in the lysosome membrane have an unusually large number of carbohydrate — sugar — groups attached to them. These sugar groups protect the membrane proteins by preventing the digestive enzymes inside the lysosome from breaking them down.

How do hydrolytic enzymes target primary lysosomes after the Golgi processes them? Proteins are targeted to primary lysosomes by the presence of a mannose-6-phosphate tag first added in the cis-Golgi, and the presence of these tags is essential for trafficking to the lysosome. These tags get recognised by mannose-6-phosphate receptors present in the trans-Golgi network, which are transmembrane glycoproteins (acquired in the RER) that target enzymes to lysosomes in vertebrates.

Adding the lysosomal targeting tag is a two-step process in which N-acetylglucosamine phosphotransferase adds a phospho-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), connecting via the phosphate group, to mannose residue(s) of the N-linked oligosaccharide precursor. Mannosidase then trims the mannose. This process only targets lysosomal enzymes because they all have a specific protein recognition sequence that the phosphotransferase binds to before transferring the phospho-GlcNAc. Then, a trans-Golgi phosphodiesterase (the uncovering enzyme) removes the GlcNAc, leaving the mannose-6-phosphate. Although the cis-Golgi tags the lysosomal enzymes, they do not get sorted until the trans-Golgi. The trans-Golgi is where the mannose-6-phosphate membrane receptors bind to the lysosomal enzymes to form clathrin-coated vesicles that bud off and travel to late endosomes to deliver their acid hydrolase payload. Again, the pH change is crucial. The receptor binds the mannose-6-phosphate-tagged enzymes in the somewhat acidic (pH 6.5) environment of the trans-Golgi. However, in the more acidic secondary lysosome, the acid hydrolases are released to do their work and the receptors are shipped back in vesicles to the trans-Golgi. The released enzymes remain in the endosome during maturation and subsequent fusion with a lysosome (Figure 15). If the Golgi does not properly tag a lysosomal enzyme, it goes down the default pathway and gets continually secreted from the cell. This process is known as constitutive secretion and occurs in I-cell disease, which results from a mutation in the gene encoding N-acetylglucosamine phosphotransferase. A reduction or loss of phosphotransferase function disrupts the phosphorylation of the lysosomal enzyme’s mannose and its subsequent targeting to the lysosome.

Materials within the cell scheduled for digestion first get deposited within lysosomes. These materials can include:

- Other organelles (e.g., mitochondria) that have ceased proper functioning and become engulfed in autophagosomes

- Food molecules or, in some cases, food particles are taken into the cell by endocytosis

- Foreign particles (e.g., bacteria) that have become engulfed by neutrophils

- Antigens that are taken up by “professional” antigen-presenting cells like dendritic cells (by phagocytosis)

- B-cells by binding to their antigen receptors, followed by receptor-mediated endocytosis

Lysosome Function

At one time, it was thought that lysosomes were responsible for killing cells scheduled for removal from a tissue. For example, a tadpole that reabsorbs its tails as it metamorphoses into a frog.

However, this is incorrect. These examples of programmed cell death (PCD) or apoptosis take place by an entirely different mechanism.

In some cells, lysosomes have a secretory function — releasing their contents by exocytosis as follows:

- Cytotoxic T-cells secrete perforin from lysosomes.

- Mast cells secrete some of their many mediators of inflammation from modified lysosomes.

- Melanocytes secrete melanin from modified lysosomes.

- Lysosome exocytosis provides the additional membrane needed to quickly seal wounds in the plasma membrane.

Finally, note that the large vacuoles in plant cells are in fact specialized lysosomes. Recall that vacuoles help maintain the turgor, or outward water pressure on the cell walls that causes a plant part to be rigid rather than limp and wilted. One way this occurs is that the acid hydrolases inside the vacuole alter the osmotic pressure to regulate water moving either in or out.

Self-Check

The mannose 6-phosphate residue is important, as it is required to target soluble enzymes to the lysosome. The phosphotransferase responsible for attaching the GlcNAc-1-phosphate residue onto the mannose of lysosomal enzymes resides in the:

- RER

- Cis-Golgi

- Medial-Golgi

- Trans-Golgi

Show/Hide answer.

b. Cis-Golgi

Lysosomal Storage Diseases

When one or more acid hydrolases do not function properly or do not make it to the lysosome due to faulty targeting, the lysosomal contents do not get properly digested. Lack of proper digestation leads to large partially-digested material forming inside lysosomes. This material accumulation can be cytotoxic. Genetic disorders affecting lysosomal hydrolase expression and sorting are collectively known as lysosomal storage diseases. These disorders fall into several categories depending on the types of molecules that accumulate. Approximately fifty of these disorders exist, and each one may affect different parts of the body. Neurons of the central nervous system are particularly susceptible to damage. Most of these diseases are caused by inheriting two defective alleles of the gene encoding one of the hydrolytic enzymes.

Lysosomal storage disease examples include the following:

- Tay-Sachs disease and Gaucher’s disease result from a failure to produce an enzyme needed to break down sphingolipids (fatty acid derivatives found in all cell membranes).

- Mucopolysaccharidosis I (MPS-I) results from a failure to synthesize the enzyme α-L-iduronidase needed to break down proteoglycans like heparan sulfate. In April 2003, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a synthetic version of the enzyme called laronidase (Aldurazyme®) as a possible treatment. Manufacturing this enzyme (containing 628 amino acids) involves recombinant DNA technology.

- Inclusion-cell (I-cell) disease results from the Golgi failing to “tag” (by phosphorylation) all hydrolytic enzymes that need to move from the Golgi apparatus to the lysosomes. The lysosomal enzymes lacking the mannose 6-phosphate tag are secreted from the cell instead. This secretion results in all the macromolecules incorporated in lysosomes remaining undegraded and forming “inclusion bodies” in the cell.

Learning Activity: Lysosomal Targeting

- Watch the video “Lysosomal Storage Diseases, Cell Introduction” (2:16 min) by Charlie Williams (2011). Review the general path of a protein destined for the lysosome.

- Watch the video “Lysosomal Storage Diseases, Lysosome Development” (4:38 min) by Charlie Williams (2011) to learn how hydrolytic enzymes get targeted to the lysosome.

- Answer the following questions:

- What tag targets a hydrolytic enzyme to the lysosome? In what organelle does this tag first get added?

- What happens after the lysosomal enzyme is tagged with mannose-6-phosphate?

- What happens if a lysosomal enzyme is not targeted to the lysosome?

Learning Activity: Protein Trafficking Summary

- Watch the video “Protein Trafficking, I-Cell Disease, Clathrin, Vesicular Transport & Protein Modifications” (19:41 min) by Med-Ace (2020) to review protein targeting for Unit 3.

- Make your own notes summarizing the five destinations of proteins translated in the ER compared to those translated on cytosolic ribosomes.

Self-Check

Label the following:

Key Concepts and Summary

The following three major vesicular transport pathways can occur after cargo is tagged and sorted in the Golgi complex:

- The secretory pathway in which vesicles transport cargo to the plasma membrane. Transport vesicles budded from the ER and carry cargo to the cis-Golgi, where budding and fusion push cargo through the Golgi stacks to the trans-side. Cargo exits the trans-Golgi, and transport vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane.

- The endocytic pathway in which vesicles containing cargo enter the cell from the plasma membrane. Early endosomes form from the plasma membrane and target cargo to late endosomes, which deliver cargo to lysosomes.

- Recycling and retrieval pathways in which vesicles transport cargo within the cell.

- Endosomes can return cargo (such as cell surface receptors) to the plasma membrane by recycling endosomes.

- Early and late endosomes can also return cargo to the Golgi.

- Vesicles deliver Golgi-resident proteins back from the trans– to the cis-Golgi.

- Vesicles return ER-resident proteins from the Golgi to the ER.

Vesicular Transport — Cargo Selection, Vesicular Budding, Vesicular Targeting and Membrane Fusion

- Cargo selection is highly regulated by sorting receptors to ensure proteins reach the correct destination within or outside the cell.

- The lipid bilayer must rearrange during vesicle formation so that it can invaginate and eventually pinch off to form the vesicle, which involves a process called budding.

- The assembly of coat proteins controls the budding of vesicles containing their cargo from the donor membrane. There are three well-characterized types of coated vesicles that have different coat proteins. Each coated vesicle is used in a different step of vesicular transport as follows:

- COPI-coated vesicles are involved in the retrograde transport of proteins from the cis-Golgi towards the ER. This ensures that ER-resident proteins, such as binding immunoglobulin protein, are retrieved by the ER where their function is required. This also returns Golgi-resident enzymes from the trans– to the cis-Golgi. COPI coats are composed of seven different coat protein subunits.

- COPII-coated vesicles are involved in the anterograde transport of proteins from the ER towards the Golgi. COPII coats are composed of four different coat protein subunits.

- Clathrin-coated vesicles have protein clathrin surrounding them, which forms a cage-like structure. Individual clathrin units have a shape called a triskelion. Adaptin proteins connect the cargo-bound membrane receptors to the clathrin triskelions, which induce a curvature in the membrane. Clathrin coats are found on vesicles transporting materials from the Golgi to endosomes and from the plasma membrane to endosomes.

- Small GTP-binding proteins ARF1 (clathrin and COPI) and Sar1 (COPII) regulate the formation of coated vesicles by recruiting adaptor proteins that link the coat proteins to the target membrane.

- It is important that transport vesicles first recognise the correct target membrane. Then, the donor and target membranes must fuse to deliver the cargo. Tethering proteins and small GTP-binding proteins called Rabs mediate this specificity. Tethering gets followed by interactions between SNAREs on the vesicle and target membranes.

- Rab-GTP on the vesicle surface binds to tethering proteins on the target membrane. This brings the vesicle and target membrane close enough for SNARE proteins to match.

- Each type of transport vesicle contains a specific v-SNARE that binds to the corresponding t-SNARE on the target membrane. If a match is made, the helical domains of the SNARE proteins coil around each other to allow the membranes to fuse.

- The SNARE complexes at neuron terminals are the targets of powerful neurotoxins secreted by the bacteria that cause tetanus and botulism. These toxins are highly specific proteases that enter specific neurons and cleave SNARE proteins in the nerve terminals, thereby blocking synaptic transmissions, often fatally.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis is an extremely selective process of importing materials into the cell. Receptor proteins located on specific areas of the cell membrane provide this specificity. Material brought into the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis occurs after the formation and budding off of clathrin-coated pits with the aid of the dynamin GTPase.

- Uncoating of vesicles occurs by ATP hydrolysis for clathrin coats and by GTP hydrolysis for COPI and COPII vesicles.

Vesicle targeting to lysosomes

- Lysosomes contain acidic hydrolytic enzymes that break down macromolecules.

- Lysosomal enzymes are tagged with mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) in the cis-Golgi and sorted into vesicles containing M6P receptors in the trans-Golgi that get delivered to lysosomes.

- I-cell disease results from a mutation in the enzyme catalyzing the addition of the M6P tag.

- Untagged proteins follow the default pathway and end up secreted from the cell. This is an example of a lysosomal storage disease resulting in the accumulation of undigested macromolecules.

Key Terms

ADP ribosylation factor (ARF)

a small GTPase that initiates the assembly of COPI- and Golgi-derived clathrin-coated vesicles

anterograde transport

movement of a vesicle away from the cell body

binding immunoglobulin protein

member of the hsp70 family of chaperones that functions in the RER to help with protein folding

cisterna (plural cisternae)

membranous flattened sac found in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus

cis-Golgi network

region adjacent to the Golgi cis-cisterna and contains membranous tubules that receives cargo from the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC)

clathrin

a protein that assembles into a polyhedral cage on the cytosolic side of a membrane. Clathrin-coated pits are visible by transmission electron microscopy when they bud off by endocytosis to form clathrin-coated vesicles

coated vesicle

a small membrane-bound vesicle that is active in the endomembrane system. They are surrounded by a coat of proteins on their cytosolic surface. The coats include either clathrin, COPI, or COPII or caveolin

COPI

a coat protein surrounding vesicles involved in retrograde transport from the Golgi back to the RER and between Golgi cisternae

COPII

a coat protein surrounding vesicles involved in anterograde transport from the RER to the cis-Golgi apparatus

dynamin

a cytosolic GTPase that plays a role in the pinching off of clathrin-coated vesicles

early endosome

formed from vesicles budding from the trans-Golgi network that sort and recycle extracellular material brought into the cell by endocytosis

ER cisterna (plural cisternae)

flattened sac of the endoplasmic reticulum

Golgi apparatus

stacks of flattened membrane cisternae in eukaryotic cells that processes and packages secretory proteins and contributes to the synthesis of complex carbohydrates

late endosome

vesicle containing acid hydrolases and cellular components for digestion

LDL receptor

an integral membrane protein that binds to extracellular low-density lipoprotein (LDL) entering the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis

ligand

a substance that binds to a receptor

lysosomal storage disease

a disease that results from the malfunctioning or absence of lysosomal enzymes resulting in the accumulation of undigested cellular material

lysosome

an organelle in an animal cell that functions as the cell’s digestive component; it breaks down proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles

medial cisternae

flattened membranous sacs of the Golgi apparatus that are located between the cis-Golgi and trans-Golgi cisternae

neurosecretory vesicle

a vesicle containing neurotransmitters that is secreted from the terminal axon region

Rab GTPase

a protein involved in hydrolyzing GTP and interlocking v-SNAREs with t-SNAREs to help a vesicle fuse with a target membrane

retrograde transport

movement of a vesicle toward the cell body

secretory pathway

the route by which newly synthesized proteins move from the RER through the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane for exocytosis

soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins

two groups of proteins located on vesicles (v-SNAREs) and on target membranes (t-SNAREs) that are involved in the fusion and sorting of vesicles

trans-Golgi network (TGN)

region adjacent to the Golgi trans-cisterna and contains membranous tubules that sort cargo into vesicles for intracellular use or for exocytosis

transport vesicle

small, membrane-bound sac that functions in cellular storage and transport; its membrane is capable of fusing with the plasma membrane and the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, endosomes and lysosomes

vacuole

membrane-bound sac, somewhat larger than a vesicle, which functions in cellular storage and transport

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 11.6.16 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 2: COPII coat by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: COPI coat by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 6.6.17 from Reyna Cell Biology (Wong 2021) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 5: Itrafig2 by B. D. Grant and M. Sato (Grant and Sato 2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 2.5 license.

- Figure 6: The assembly of clathrin-coated vesicles… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Clathrin-coated vesicles from the membrane… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 10-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 10-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 11.7.22 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

- Figure 11: Figure 10-7 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 10-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 10-9 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: The binding of ligands to… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Figure 3.8.1, by Matthew R G Russell is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

BioDigital. 2020. COVID infection with and without vaccination [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:52c3fd7e:lx_simulation:1.

BioInteractive. 2021. Biology of SARS-CoV-2 [interactive animation]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://media.hhmi.org/biointeractive/click/covid/.

Biology Help. Clathrin full rendering [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Dec 20, 2:10 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ycp4hmaYEGc.

Cell Bio Clips. Vesicle budding (vesicle transport and formation) [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Mar 1, 6:10 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ecw1xYInizs.

Cell Bio Clips. Vesicle fusion (membrane docking and cargo release) [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Mar 1, 5:05 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cP7g4TLSgrI.

Cell Bio Clips. Receptor-mediated endocytosis overview (process of endocytosis and maturation of endosomes) [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Apr 3, 6:00 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0xAOmxWWfM.

Charlie Williams. Lysosomal storage diseases, cell introduction [Video]. YouTube. 2011 Aug 21, 2:16 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTIxkXyMhzY.

Charlie Williams. Lysosomal storage diseases, lysosome development [Video]. YouTube. 2011 Aug 21, 4:38 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-q8voqiXmF8.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Chapter 4.4: the endomembrane system and proteins. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/4-4-the-endomembrane-system-and-proteins.

Ditki – Medical & Biological Sciences. Cell and molecular biologyvesicular budding and fusion [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Jan 27, 7:40 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OE82CDxjwHI.

Grant BD, Sato M. 2006. Itrafig2 [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2012 Jan 8, accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Itrafig2.jpg.

JS Muscle Science. BOTOX mechanism of action – JS Muscle Science [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Aug 1, 1:33 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GG4mAqEZOE4.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 10: vesicles in the endomembrane system. Figures 10-4, 10-5, 10-7 to 10-9. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/adfe0fac-6ce5-44dd-a1a0-3cc273db147f.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. The endomembrane system. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jul 23]. AP®︎/college biology, Lesson 8: cell compartmentalization and its origins. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/cell-compartmentalization-and-its-origins/a/the-endomembrane-system.

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball).

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 3.8: lysosomes and peroxisomes. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball)/03%3A_The_Cellular_Basis_of_Life/3.08%3A_Lysosomes_and_Peroxisomes.

Med-Ace. Protein trafficking, I-cell disease, clathrin, vesicular transport & protein modifications [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Mar 7, 19:41 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4sWnK7OqK-k.

Neuroscientifically Challenged. 2-minute neuroscience: neurotransmitter release [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Mar 30, 2:00 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIIK2Gp5WzU.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2024. Membrane vesicle trafficking. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2024 Jan 20; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Membrane_vesicle_trafficking&oldid=1197403998.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Receptor-mediated endocytosis. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Dec 3; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Receptor-mediated_endocytosis&oldid=1188107980.

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 11.7: receptor-mediated endocytosis. Figures 11.6.16, 11.7.22. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong)/11%3A_Protein_Modification_and_Trafficking/11.07%3A_Receptor-mediated_Endocytosis.

Wong EV. 2021. Reyna cell biology. Arkadelphia (AR): Ouachita Baptist University; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Ouachita_Baptist_University/Reyna_Cell_Biology.

Wong EV. 2021. Reyna cell biology. Arkadelphia (AR): Ouachita Baptist University; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 6.6: vesicular transport. Figure 6.6.17. https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Ouachita_Baptist_University/Reyna_Cell_Biology/06%3A_(T2)_Protein_Modification_and_Trafficking/6.06%3A_Vesicular_Transport.

Zedalis J, Eggebrecht J. 2018. Biology for AP ® courses. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction.

Zedalis J, Eggebrecht J. 2018. Biology for AP ® courses. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 5.4: bulk transport. https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/5-4-bulk-transport.

Yang J-L J. 2022. Figures 2, 3, 6, 7, 14 (created for this course).

small, membrane-bound sac that functions in cellular storage and transport; its membrane is capable of fusing with the plasma membrane and the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, endosomes and lysosomes

stacks of flattened membrane cisternae in eukaryotic cells that processes and packages secretory proteins and contributes to the synthesis of complex carbohydrates

flattened membranous sacs of the Golgi apparatus that are located between the cis-Golgi and trans-Golgi cisternae

member of the hsp70 family of chaperones that functions in the RER to help with protein folding

a coat protein surrounding vesicles involved in anterograde transport from the RER to the cis-Golgi apparatus

a coat protein surrounding vesicles involved in retrograde transport from the Golgi back to the RER and between Golgi cisternae

protein that coats the inward-facing surface of the plasma membrane and assists in the formation of specialized structures, like coated pits, for phagocytosis

movement of a vesicle away from the cell body

movement of a vesicle toward the cell body

a small membrane-bound vesicle that is active in the endomembrane system. They are surrounded by a coat of proteins on their cytosolic surface. The coats include either clathrin, COPI, or COPII or caveolin

membranous flattened sac found in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus

a small GTPase that initiates the assembly of COPI- and Golgi-derived clathrin-coated vesicles

molecule that binds with specificity to a specific receptor molecule

a cytosolic GTPase that plays a role in the pinching off of clathrin-coated vesicles

an integral membrane protein that binds to extracellular low-density lipoprotein (LDL) entering the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis

an organelle in an animal cell that functions as the cell’s digestive component; it breaks down proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles

formed from vesicles budding from the trans-Golgi network that sort and recycle extracellular material brought into the cell by endocytosis

a protein involved in hydrolyzing GTP and interlocking v-SNAREs with t-SNAREs to help a vesicle fuse with a target membrane

two groups of proteins located on vesicles (v-SNAREs) and on target membranes (t-SNAREs) that are involved in the fusion and sorting of vesicles

vesicle containing acid hydrolases and cellular components for digestion

region adjacent to the Golgi trans-cisterna and contains membranous tubules that sort cargo into vesicles for intracellular use or for exocytosis

membrane-bound sac, somewhat larger than a vesicle, which functions in cellular storage and transport

a disease that results from the malfunctioning or absence of lysosomal enzymes resulting in the accumulation of undigested cellular material

the route by which newly synthesized proteins move from the RER through the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane for exocytosis