2.4 Membrane Potentials and Nerve Impulses

Introduction

The amazing cloud-to-surface lightning shown in Figure 1 occurred when a difference in electrical charge built up in a cloud relative to the ground. When the charge buildup was great enough, a sudden electricity discharge occurred. Interestingly, a nerve impulse, which is an important way to communicate in the nervous system, is like a lightning strike because both occur due to differences in electrical charge and result in an electric current.

All nervous system functions — from a simple motor reflex to more advanced functions (e.g., making a memory or a decision) — require neurons to communicate with one another. While humans communicate through words and body language, neurons use electrical and chemical signals. Like a person in a committee, one neuron usually receives and synthesizes messages from multiple other neurons before “making the decision” to send the message to other neurons.

For the nervous system to function, neurons must be able to send and receive signals. These signals are possible because each neuron has a charged cellular membrane, also termed the membrane potential (a voltage difference between the inside and the outside). The charge of this membrane can change in response to chemicals called neurotransmitters released from other neurons and environmental stimuli. Understanding the baseline, or resting membrane potential, is critical for understanding how neurons communicate.

Unit 2, Topic 4 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 2, Topic 4, you will be able to:

- Describe the membrane components that establish the resting membrane potential.

- Explain how electrochemical gradients affect ions during a nerve impulse.

- Describe the changes that occur to the membrane that result in the action potential, applying the terms polarized, depolarized, and repolarized.

- Compare the process of action potential propagation in a myelinated neuron and an unmyelinated neuron.

- Explain how neurotransmitters are used in neuronal communication.

- Explain the similarities and differences between chemical and electrical synapses.

| Unit 2, Topic 4—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 2, Topic 4 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane Potential. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Action Potential. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Parts of the Neuron. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Nerve Fibers. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neuron Action Potential. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neuronal Structure. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Synaptic clefts. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neurotransmitter release. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neurotransmitter-Receptor Interactions. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: GABA. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neural Control. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Electrical Activity in Neurons. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Neural Transmission. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Myelinated Neuron Model. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Visualizing Neuronal activity. | 10 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 2 Quiz. | 12 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 2 Assignment. | 100 |

Electrically Active Cell Membranes

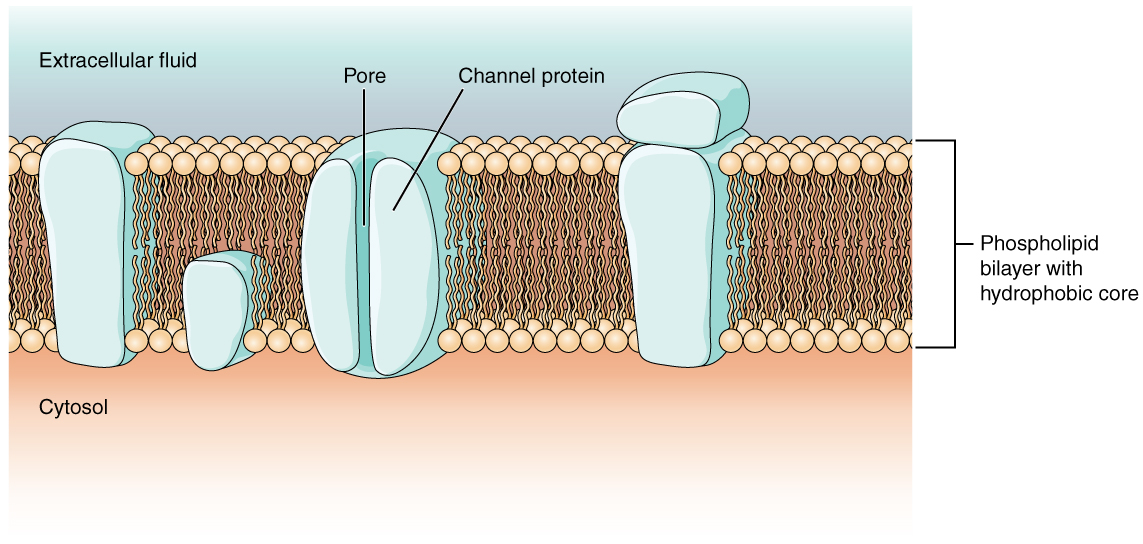

Most cells in the body use charged particles (ions) to build up a charge across the cell membrane. As previously mentioned in the topic on cells, the cell membrane is primarily responsible for regulating what can cross the membrane and what stays on only one side. The cell membrane is a phospholipid bilayer, so only substances that can pass directly through the hydrophobic core can diffuse through unaided. Charged particles, which are hydrophilic, cannot pass through the cell membrane without assistance (Figure 2). Transmembrane proteins, specifically channel proteins, make this possible. Several passive transport channels, as well as active transport pumps, are necessary to generate a transmembrane potential and an action potential. Of special interest is the carrier protein referred to as the sodium/potassium pump that moves sodium ions (Na+) out of a cell and potassium ions (K+) into a cell, thus regulating ion concentration on both sides of the cell membrane.

Since the sodium/potassium pump requires energy from adenosine triphosphate (ATP), it is also known as an ATPase. As explained in Unit 2, Topic 3, the Na+ concentration is higher outside the cell than inside, and the K+ concentration is higher inside the cell than outside. That means this pump moves the ions against the concentration gradients for sodium and potassium, which is why it requires energy. In fact, the pump basically maintains those concentration gradients.

Ion channels are pores that allow specific charged particles to cross the membrane in response to an existing concentration gradient. Proteins can span the cell membrane, including their hydrophobic core, and interact with the ion charges due to amino acids with varied properties within specific domains or regions in the protein channel. Specifically, the domains apposed to the phospholipid hydrocarbon tails have hydrophobic amino acids exposed to the fluid environments that make up extracellular fluid and cytosol. Additionally, the ions interact with the hydrophilic amino acids, which are specific to the ion’s charge. Channels for cations (positive ions) have negatively charged side chains in the pore, while channels for anions (negative ions) have positively charged side chains. This is called electrochemical exclusion, meaning that the channel pore is charge-specific.

Ion channels can also be defined by the diameter of the pore. The distance between the amino acids will be specific to the diameter of the ion when it dissociates from the water molecules surrounding it. Due to the surrounding water molecules, larger pores are not ideal for smaller ions because the water molecules will interact, by hydrogen bonds, more readily than the amino acid side chains. This is called size exclusion. Some ion channels are selective for charge but not necessarily for size and thus are called nonspecific channels. These nonspecific channels allow cations — particularly Na+, K+, and Ca2+ — to cross the membrane but exclude anions. These anions are organic anions present in the interior of the cell. Often, these anions are the negatively charged amino acid side chains making up large, bulky proteins that remain trapped inside the cell. Thus, organic anions generally cannot cross the membrane like Na+ and K+.

Ion channels do not always freely allow ions to diffuse across the membrane. Some are opened by certain events, meaning the channels are gated. Therefore, another way that channels can be categorized is by how they are gated. Although these classes of ion channels are found primarily in the cells of nervous or muscular tissue, they also can be in epithelial and connective tissue cells.

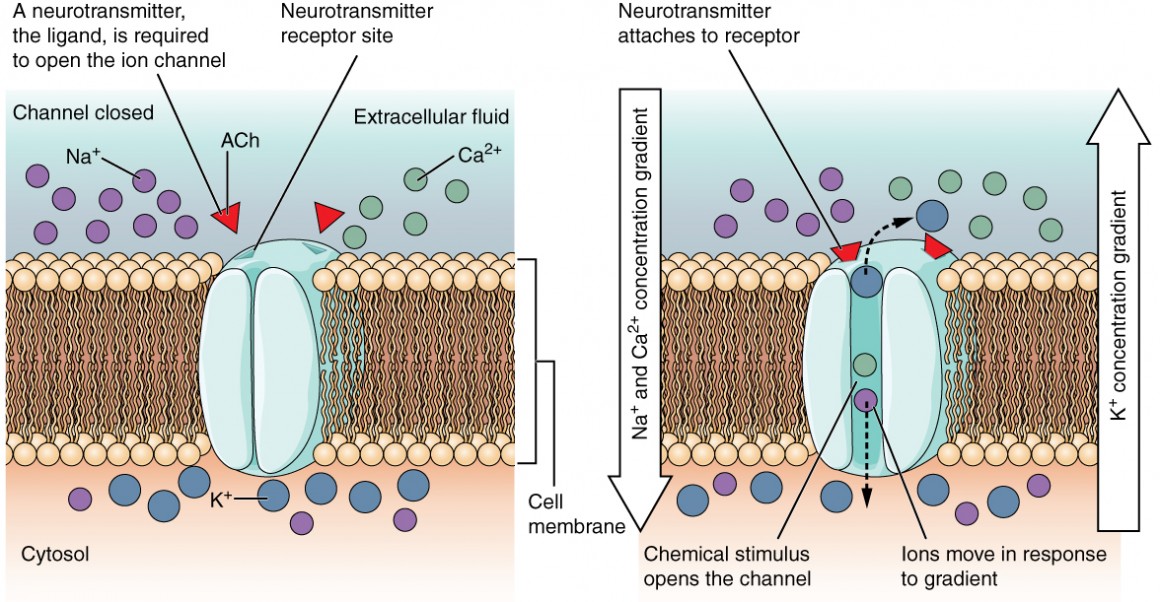

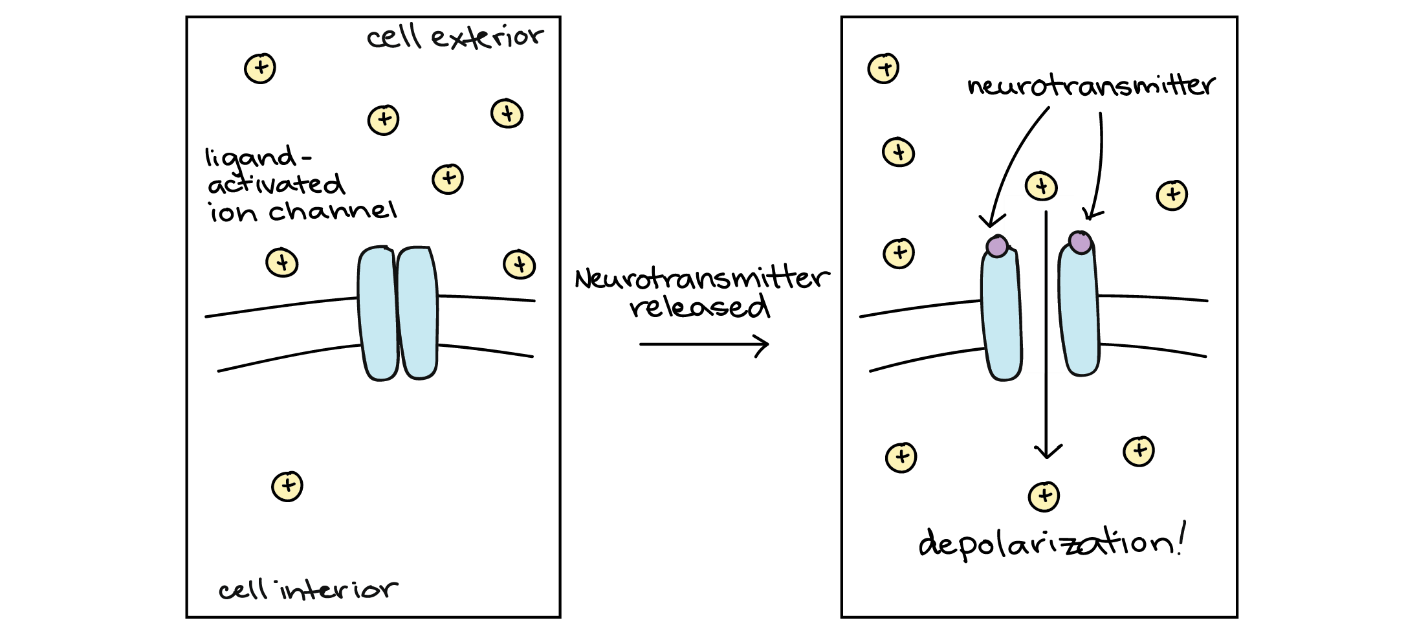

A ligand-gated channel opens because a signalling molecule (ligand) binds to the extracellular region of the channel. For example, ionotropic receptors, a receptor class in the nervous system, allow cations to cross the cell membrane only when the receptor is bound to a neurotransmitter as the ligand (Figure 3).

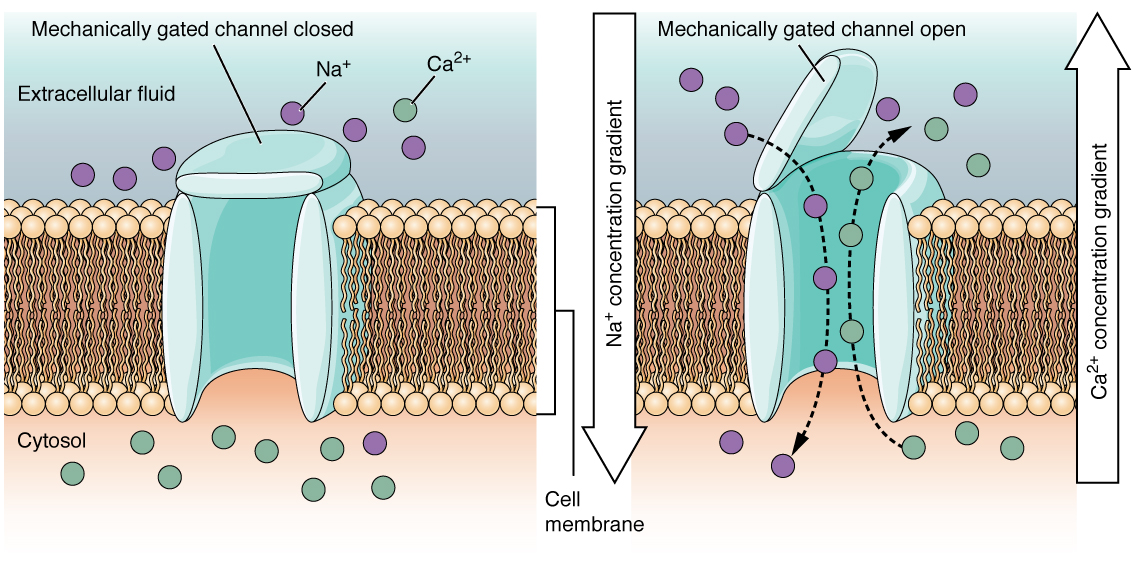

A mechanically gated channel opens due to a physical distortion in the cell membrane. Many channels associated with the sense of touch (somatosensation) are mechanically gated. For example, pressure applied to the skin causes these channels to open, which allows ions to enter the cell. Similar to this type of channel would be the channel that opens when the temperature changes, as in testing the water in the shower (Figure 4).

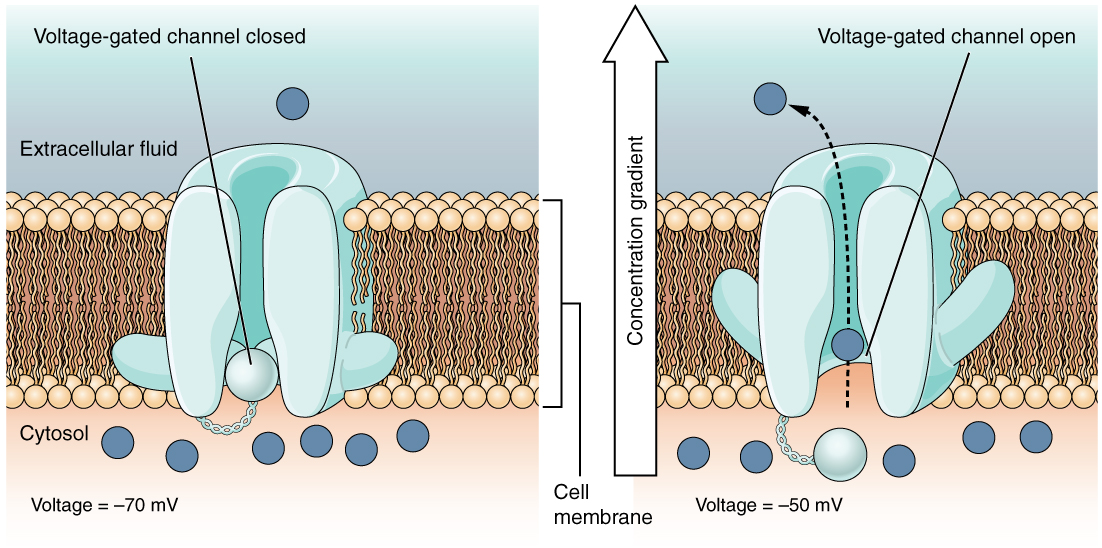

A voltage-gated channel is a channel embedded in the membrane that responds to changes in the electrical properties of the membrane. Normally, the inner portion of the membrane is at a negative voltage. When that voltage becomes less negative, the channel allows ions to cross the membrane (Figure 5).

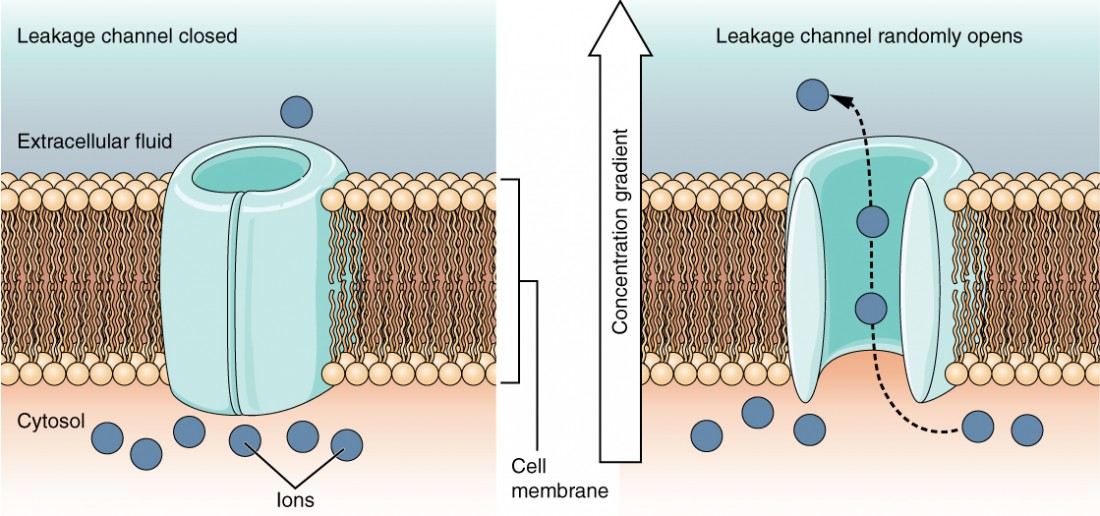

A leakage channel is randomly gated, meaning that it opens and closes at random (hence the reference to leaking). There is no actual event that opens the channel; instead, it has an intrinsic switching rate between the open and closed states. Leakage channels contribute to the resting transmembrane voltage in the excitable membrane (Figure 6).

Resting Membrane Potential

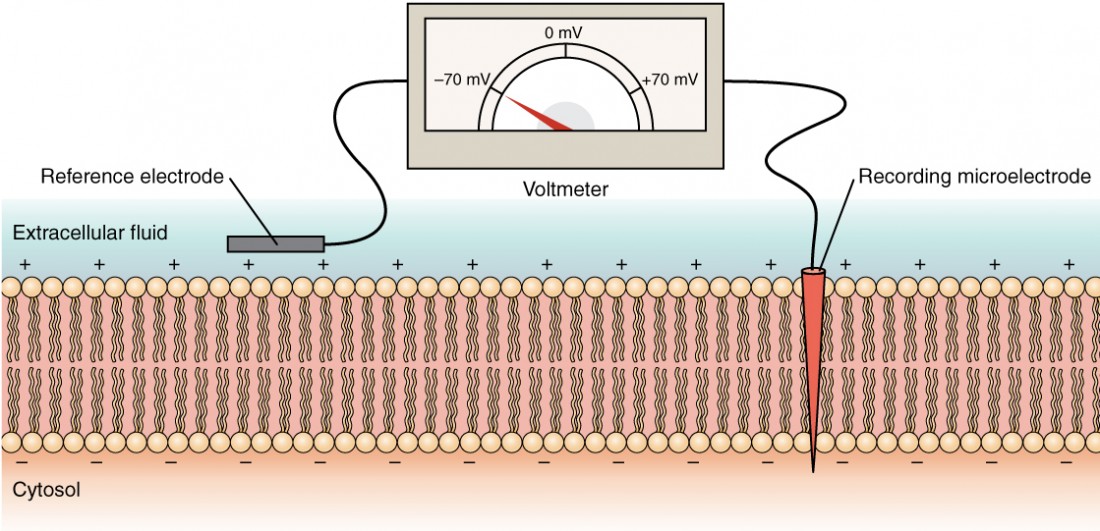

In neurons, the resting membrane potential depends mainly on K+ ions moving through potassium leak channels. How does this work? Cell membranes have several variations in their electrical state. These are all variations in the membrane potential. A potential is a charge distribution across the cell membrane, measured in millivolts (mV). The standard is to compare the inside of the cell relative to the outside. As such, the membrane potential is a value representing the charge on the intracellular side of the membrane based on the outside being zero, relatively speaking (Figure 7).

Measuring charge across a membrane involves inserting a recording electrode into the cell and placing a reference electrode outside the cell. Comparing the charges measured by these two electrodes determines the transmembrane voltage. It is conventional to express the cytosol value relative to the outside.

The ion concentration in extracellular and intracellular fluids is largely balanced, with a net neutral charge. However, a slight difference in charge occurs right at the membrane surface, both internally and externally. The difference in this very limited region in neurons and muscle cells holds all the power they use to generate electrical signals, including action potentials.

Before describing these electrical signals, the resting state of the membrane must be explained. A resting neuron has a negatively charged cytoplasm. A cell’s interior is approximately 70 millivolts more negative than the outside (−70 mV, but this number varies by neuron type and species). The negative charge within the cell is created by increased permeability in the cell membrane to potassium ion movement compared to sodium ion movement. In neurons, potassium ions are maintained at high concentrations within the cell, while sodium ions are at high concentrations outside the cell. The cell possesses potassium and sodium leakage channels that allow the two cations to diffuse down their concentration gradients. However, neurons have far more potassium leakage channels than sodium leakage channels. Therefore, potassium diffuses out of the cell much faster than sodium leaks inside. Because more cations leave the cell than enter, the interior of the cell becomes negatively charged relative to the outside of the cell. This difference in voltage is the resting membrane potential (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Consider how K+ ions move down their concentration gradient to cross the membrane and move from inside to outside the cell. For ions (as for magnets), like charges repel each other while unlike charges attract. Therefore, the established electrical potential difference across the membrane makes it harder for the remaining K+ inside the cell to leave the cell. The positively charged K+ ions remaining inside the cell will be attracted to the free negative charges inside the cell membrane and repelled by the positive charges on the outside, opposing their movement down the concentration gradient. Therefore, the electrical and diffusional forces influencing K+ ion movement across the membrane jointly form its electrochemical gradient (the gradient of potential energy that determines in which direction K+ will flow spontaneously).

Eventually, the electrical potential difference across the cell membrane builds up to a high enough level that the electrical force driving K+ back into the cell equals the chemical force driving K+ out of the cell. When the potential difference across the cell membrane reaches this point, there is no net movement of K+ in either direction. The system is in equilibrium, which means every time one K+ leaves the cell, another K+ will enter it. The electrical potential difference across the cell membrane that exactly balances the concentration gradient for an ion is known as the equilibrium potential. Because the system is in equilibrium, the membrane potential will tend to stay at the equilibrium potential.

Therefore, the negative resting membrane potential is created and maintained by increasing the cation concentration outside the cell (in the extracellular fluid) relative to inside the cell (in the cytoplasm). Alternatively, if the membrane were equally permeable to all ions and there was no way to pump ions against their concentration gradient, each ion type would flow across the membrane, and the system would reach equilibrium (0 mV). Because ions cannot simply cross the membrane at will, there are different concentrations for several ions inside and outside the cell.

The sodium-potassium pump helps maintain the resting potential once established. Recall that the sodium-potassium pump transports two K+ ions into the cell while removing three Na+ ions per ATP consumed. As the cell expels more cations than it takes in, the inside of the cell becomes more negatively charged relative to the extracellular fluid.

As stated above, the sodium-potassium pump moves sodium and potassium ions against their concentration gradients. This results in a higher sodium concentration outside the cell (extracellular space) and a higher potassium concentration inside the cell (cytoplasm). There is usually approximately 145 mM Na+ outside the cell and 155 mM K+ concentration inside the cell. Other ions also have unequal concentrations inside the cell (cytoplasm) and outside the cell (extracellular space). For example, chloride ions (Cl–) tend to accumulate outside rather than inside the cell, typically at approximately 120 mM. Meanwhile, calcium ions (Ca2+) typically have a higher concentration outside the cell than inside. The difference in ions facilitates molecule transport, like glucose moving into the epithelial cells in the small intestine, and sends a signal through a nerve cell. Interestingly, organelles such as the lysosome and ER have a unique ion environment maintained by their organelle membrane that differs from that in the cytoplasm; this difference helps these organelles in their specialized functions.

Self-Check

- The Na+ and K+ concentration gradients across the membrane of a neuron (and thus, the resting membrane potential) are maintained by the activity of a protein called the Na+/K+ ATPase. Can you explain why this pump is needed to maintain the Na+ and K+ concentration gradients?

Show/Hide answer.

At the resting membrane potential of a neuron, neither Na+ nor K+ is at its equilibrium potential. The membrane potential is less negative than the K+ equilibrium potential but less positive than the Na+ equilibrium potential. Thus, there will be a steady leak of K+ out of the cell and of Na+ into the cell. The activity of the pump opposes these leaks and maintains the ions’ concentration gradients.

- How does the sodium-potassium pump affect water balance of a cell? Try to explain in the context of what would happen to water flow if there was no pump.

Show/Hide answer.

A cell’s osmolarity is the sum of the concentrations of the various ion species and many proteins and other organic compounds inside the cell. The sodium-potassium pump plays a crucial role in maintaining the osmotic balance of the cell. Without the pump, intracellular osmolarity would exceed extracellular osmolarity at electrochemical equilibrium. When this is higher than the osmolarity outside the cell, water flows into the cell through osmosis. This movement can cause the cell to swell and burst (lyse).

Learning Activity: Membrane Potential

Membrane potential refers to the difference in charge between the inside and outside of a neuron created from unequal ion distribution on both sides of the cell membrane. This unequal distribution results from membrane permeability due to leak channels and electrochemical gradients. Specific mechanisms maintain membrane potential, like the sodium-potassium pump. Understanding membrane potential is crucial to understanding what happens during an action potential.

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Membrane Potential” (2:01 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2014). Make your own notes, and keep a copy for study purposes.

Action Potential

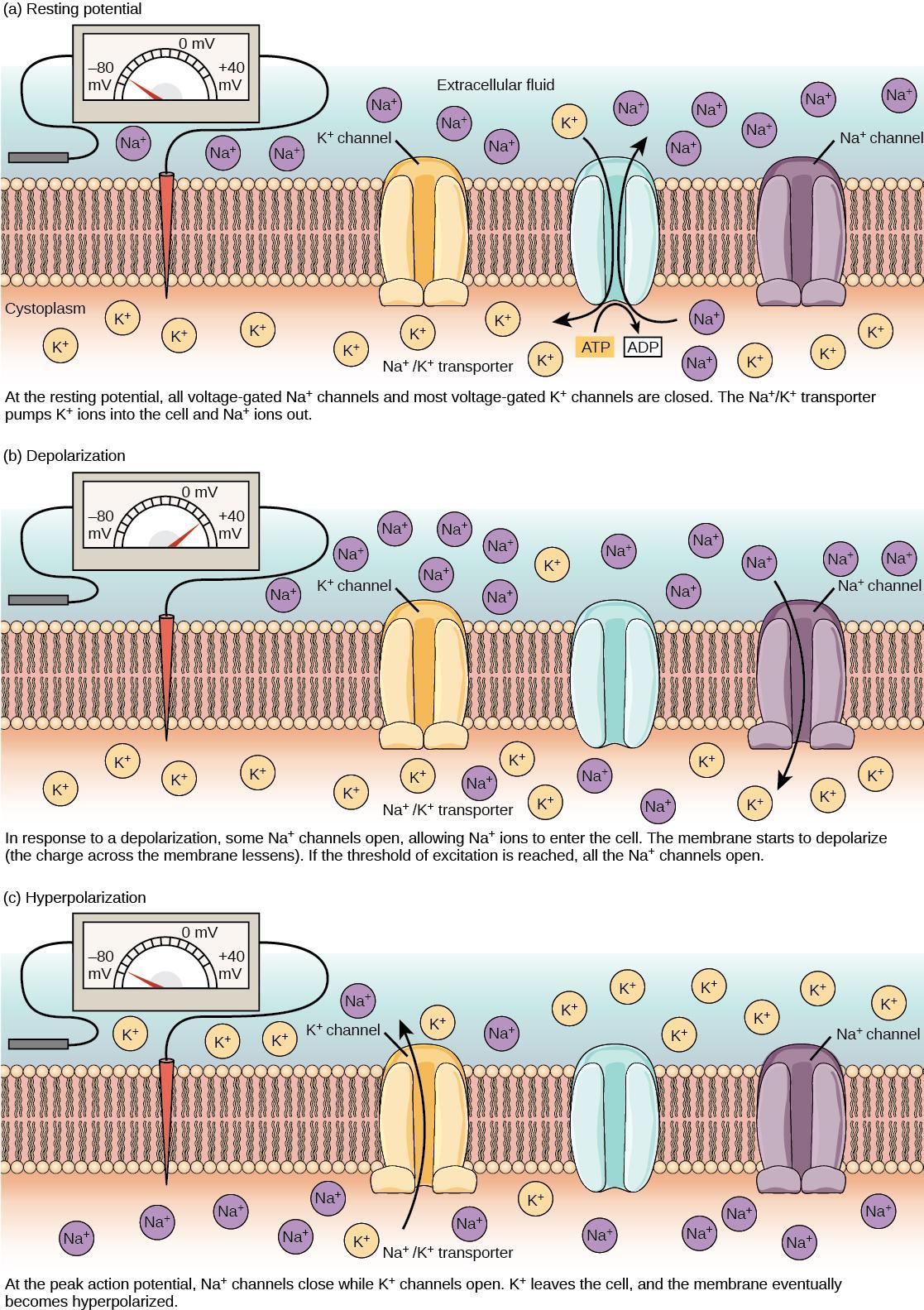

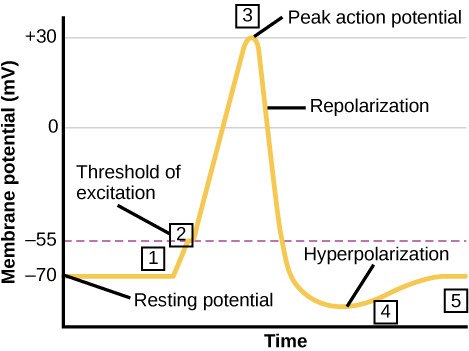

A neuron can receive input from other neurons and, if this input is strong enough, send the signal to downstream neurons. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that carry out signal transmission between neurons. When the resting membrane potential briefly reverses, an action potential occurs, carrying the electrical signal transmission within a neuron (from dendrite to axon terminal). The action potential involves the depolarization of the membrane potential as the interior face of the membrane becomes more positive and a recovery phase called hyperpolarization to restore the resting potential (Figure 9). When neurotransmitter molecules bind to receptors on a neuron’s dendrites, the chemical signal (neurotransmitter) converts to an electrical signal and ligand-gated ion channels open. At excitatory synapses, ion channel open to allow positive ions to enter the neuron, which results in membrane depolarization and decreases the difference in voltage between the inside and outside of the neuron. A stimulus from a sensory cell or another neuron depolarizes the target neuron to its threshold of excitation (–55 mV). Reaching this threshold causes Na+ channels in the axon hillock to open, allowing positive ions to enter the cell (Figure 9). Once the sodium channels open, the neuron completely depolarizes to a membrane potential of about +40 mV.

Action potentials are considered an “all-or-nothing” event because once it reaches threshold potential, the neuron always completely depolarizes (reaches +40 mV). When a given neuron fires, the action potential always depolarizes to the same magnitude and always travels at the same speed along the axon. There is no such thing as a bigger or faster action potential. The parameter that can vary is the frequency of action potentials, which is how many action potentials occur in a given amount of time. Once depolarization is complete, the cell must “reset” its membrane voltage to the resting potential. This reset means the Na+ channels close and cannot reopen for a short time, which begins the neuron’s refractory period. It cannot produce another action potential during this time because its sodium channels will not open. At the same time, voltage-gated K+ channels open, allowing K+ to leave the cell. As K+ ions leave the cell, the membrane potential once again becomes negative. Diffusing K+ out of the cell hyperpolarizes the cell, which means the membrane potential becomes more negative than the cell’s normal resting potential. At this point, the sodium channels will return to their resting state, meaning they are ready to open again if the membrane potential exceeds the threshold potential. Eventually, the extra K+ ions diffuse into the cell through the potassium leakage channels. This diffusion brings the cell from its hyperpolarized state to its resting membrane potential.

Figure 9 illustrates the membrane potential in millivolts versus time. The membrane remains at the resting potential of –70 millivolts until a nerve impulse occurs in step 1. Ligand-gated sodium channels open, and the potential begins to rapidly climb past the threshold of excitation at –55 millivolts, where signals voltage-gated sodium channels open. At the peak action potential, the potential begins to drop as voltage-gated potassium channels open and sodium channels close rapidly. As a result, the membrane repolarizes past the resting membrane potential and becomes hyperpolarized. The membrane potential then gradually returns to normal.

Self-Check

Potassium channel blockers impede the movement of K+ through voltage-gated K+ channels. Examples include amiodarone and procainamide, used to treat abnormal electrical activity in the heart, called cardiac dysrhythmia.

Which part of the action potential would you expect potassium channels to affect?

Show/Hide answer.

Potassium channel blockers slow the repolarization phase but do not affect depolarization.

Learning Activity: Action Potential

The term “action potential” refers to the electrical signalling that occurs within neurons. This electrical signalling leads to the release of neurotransmitters and, therefore, is important to the chemical communication that occurs between neurons. Thus, understanding action potential is important to understanding how neurons communicate.

- Watch this video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Action Potential” (2:01 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2014). Make your own notes, and keep a copy for study purposes.

Propagation of the Action Potential

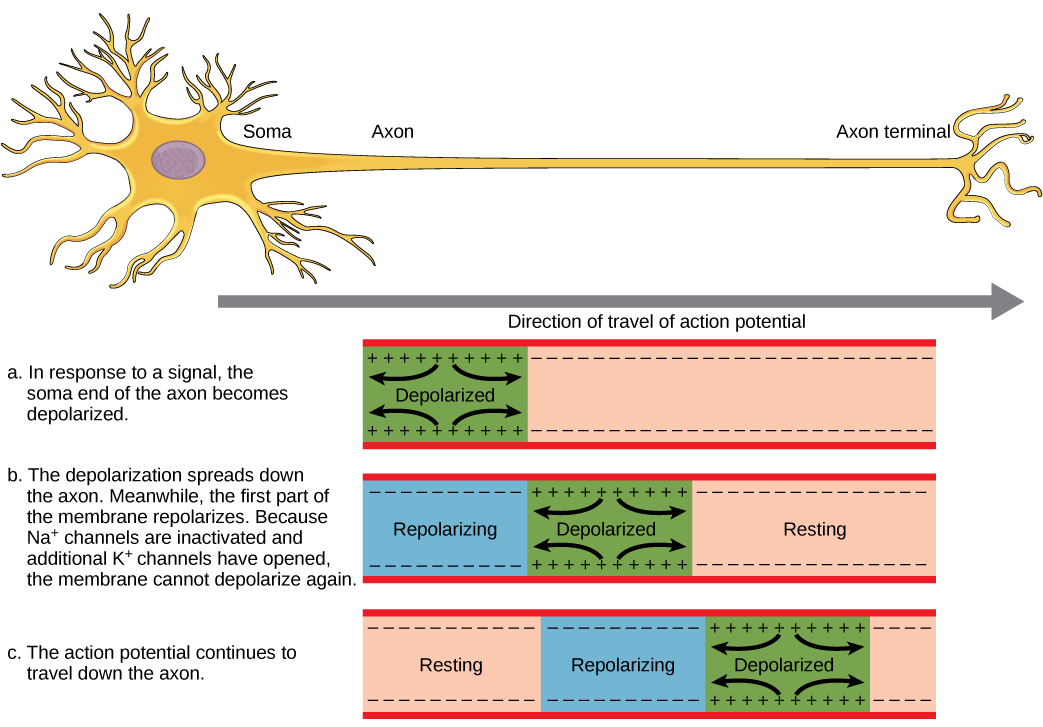

The action potential initiates at the beginning of the axon, at what is called the initial segment. The initial segment has a high density of voltage-gated Na+ channels, allowing for rapid depolarization (Figure 10). As the action potential goes down the length of the axon, it is propagated because more voltage-gated Na+ channels open as the depolarization spreads. This spreading occurs because Na+ enters through the channel and moves along the inside of the cell membrane. As the Na+ moves, or flows, a short distance along the cell membrane, its positive charge depolarizes a little more of the cell membrane. As that depolarization spreads, new voltage-gated Na+ channels open and more ions rush into the cell; this spreads the depolarization a little further.

Because voltage-gated Na+ channels inactivate at the peak of the depolarization, they cannot open again for a brief time — the absolute refractory period. Because of this, depolarization spreading back toward previously opened channels has no effect. The action potential must propagate toward the axon terminals; this maintains the polarity of the neuron, as mentioned above.

As seen previously, action potential depolarization and repolarization depend on two types of channels (the voltage-gated Na+ channel and the voltage-gated K+ channel). The voltage-gated Na+ channel actually has two gates. One is the activation gate, which opens when the membrane potential crosses –55 mV. The other gate is the inactivation gate, which closes after a specific period of time — on the order of a fraction of a millisecond. When a cell is at rest, the activation gate is closed while the inactivation gate is open. However, when the membrane potential reaches its threshold, it causes the activation gate to open, allowing Na+ to rush into the cell. As soon as depolarization peaks, the inactivation gate closes. During repolarization, no more sodium can enter the cell. When the membrane potential passes –55 mV again, the activation gate closes. After that, the inactivation gate re-opens, making the channel ready to start the whole process over again.

The voltage-gated K+ channel has only one gate sensitive to a membrane voltage of –50 mV. However, it does not open as quickly as the voltage-gated Na+ channel. It may take the channel a fraction of a millisecond to open once it reaches that voltage. This timing coincides exactly with when the Na+ flow peaks, so voltage-gated K+ channels open just as the voltage-gated Na+ channels inactivate. As the membrane potential repolarizes and the voltage passes –50 mV again, the channel closes — again, with a little delay. For a short while, potassium continues to leave the cell, and the membrane potential becomes more negative, resulting in the hyperpolarizing overshoot. Then, the channel closes again, and the membrane can return to its resting potential due to ongoing activity in the non-gated channels and the Na+/K+ pump.

Action potentials always proceed in only one direction, from the cell body (soma) to the synapse(s) at the end of the axon. Action potentials never go backward due to the refractory period of voltage-gated ion channels, where the channels cannot re-open for a period of 1-2 milliseconds after they have closed. The refractory period forces the action potential to travel in only one direction.

Self-Check

Voltage-gated ion channels are essential for producing an action potential and returning a neuron to its resting state. Why would triggering an action potential without voltage-gated ion channels be impossible?

Show/Hide answer.

The cell would not undergo depolarization, repolarization, and hyperpolarization, which are necessary to fire an action potential and then return the cell to its resting state.

Learning Activity: Parts of the Neuron

Briefly review the parts of a neuron and relevant terminology, including the dendrites, soma, axon hillock, axon, and axon terminals (or synaptic boutons). It is important to understand how a signal travels from the dendrites of a neuron, down the axon, and to the axon terminals to communicate with another neuron through the release of neurotransmitters.

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: The Neuron” (1:47 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2014). Make your own notes, and keep a copy for study purposes.

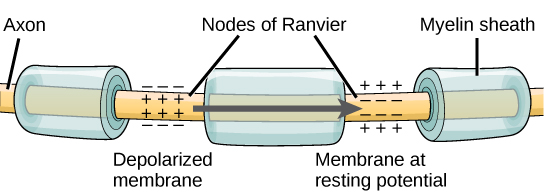

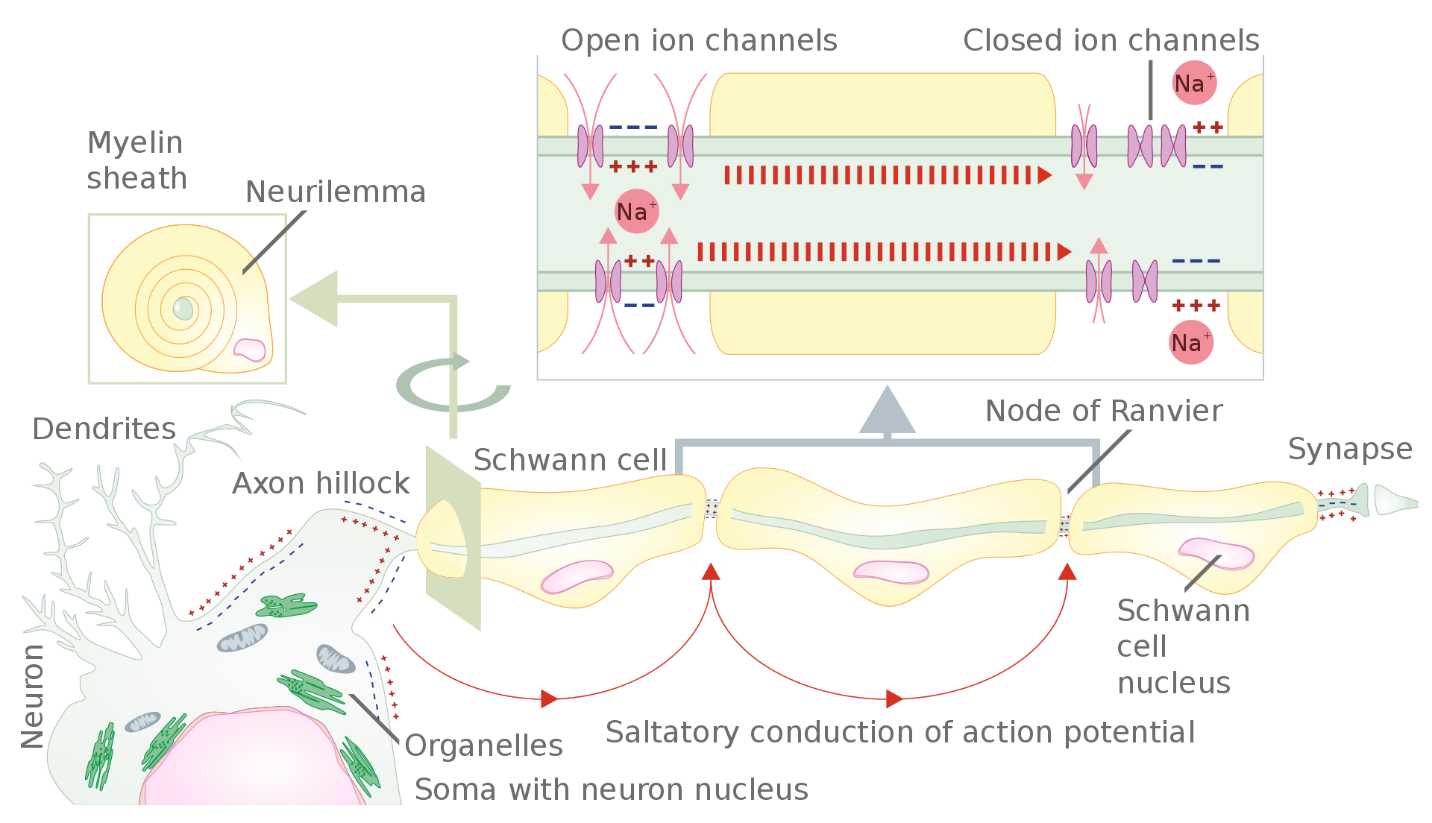

Myelin and the Propagation of the Action Potential

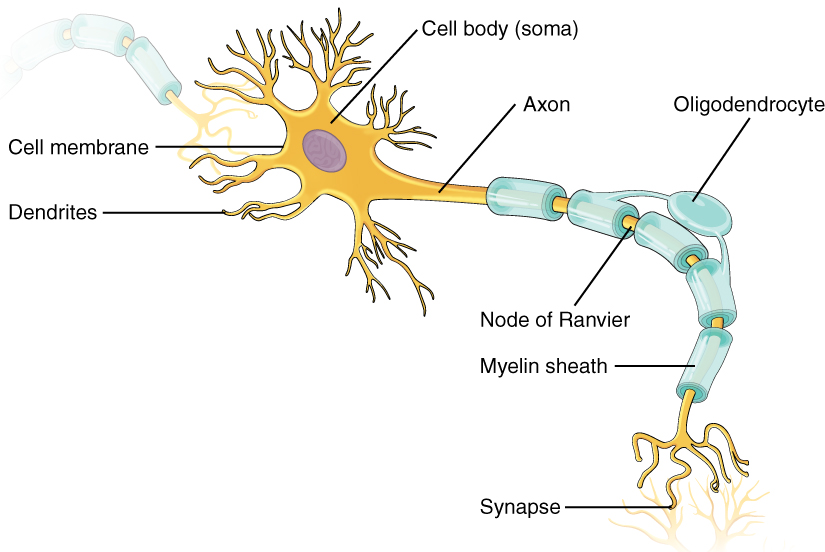

Communicating information to another neuron requires an action potential to travel along the axon and reach the axon terminals, where it can initiate neurotransmitter release. Propagation, as described above, applies to unmyelinated axons, and it is referred to as continuous conduction. When myelination is present, the action potential propagates differently. Myelin acts as an insulator that prevents current from leaving the axon; this increases the speed of action potential conduction (Figure 11). In demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis, action potential conduction slows because current leaks from previously insulated axon areas.

Glial cells provide insulation for axons in the nervous system: oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. Although the manner glial cells use to insulate their corresponding axon segments differs, how an axon segment is myelinated is mostly the same. Myelin is a lipid-rich sheath that surrounds the axon to create a myelin sheath that facilitates electrical signal transmission along the axon. The lipids are essentially the phospholipids in the glial cell membrane. Myelin, however, is more than just the membrane of the glial cell. It also includes important proteins integral to that membrane. Some of the proteins help hold the layers of the glial cell membrane closely together.

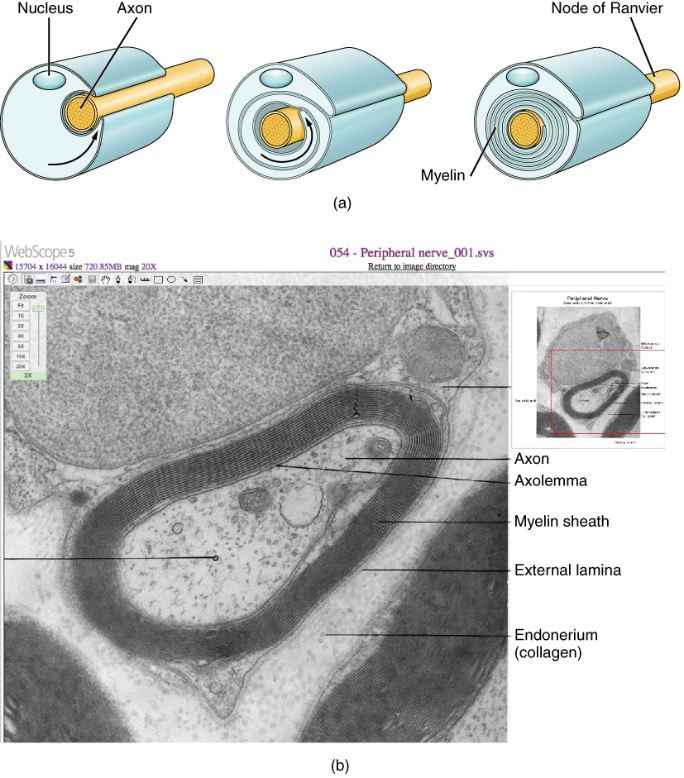

A myelin sheath looks similar to the pastry wrapped around a hot dog called “pigs in a blanket” or in similar foods (Figure 12a). The glial cell wraps around the axon several times with little to no cytoplasm between the glial cell layers. For oligodendrocytes, the rest of the cell is separate from the myelin sheath, and a cell process extends back toward the cell body. A few other processes provide the same insulation for other axon segments in the area. For Schwann cells, the outermost cell membrane layer contains cytoplasm, and the nucleus appears as a bulge on one side of the myelin sheath. During development, the glial cell loosely or incompletely wraps around the axon (Figure 12a). The edges of this loose enclosure extend toward each other, and one end tucks under the other. The inner edge wraps around the axon, creating several layers, and the other edge closes around the outside so that the axon is completely enclosed. A plasma membrane called the axolemma surrounds the axon and gives it its excitability (Figure 12b). (Figure 12b).

Myelin sheaths can extend for one or two millimetres, depending on the axon’s diameter. Axon diameters can be as small as one to 20 micrometres. Because a micrometre is 1/1000 of a millimetre, a myelin sheath can have a length 100 to 1000 times the diameter of the axon.

Learning Activity: Nerve Fibers

Figure 12 shows an electron micrograph with a cross-section of a myelinated nerve fiber in the peripheral nervous system. This axon contains microtubules and neurofilaments bound by a plasma membrane known as the axolemma. Outside the axon’s plasma membrane is the myelin sheath, which is composed of the Schwann cell’s tightly wrapped plasma membrane. This activity allows you to integrate what you learned about microscopy in Unit 1, Topic 3.

- In this image, what aspects of the cells react with the stain that makes them the deep, dark, black colour?

The nodes of Ranvier, further illustrated in Figure 13 and Figure 14, are gaps in the myelin sheath along the axon. These unmyelinated spaces are about one micrometre long and contain voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels. Sodium ions entering the cell at the initial segment start to spread along the length of the axon segment, but no voltage-gated Na+ channels exist until the first node of Ranvier. Ions flowing through these channels, particularly the Na+ channels, regenerate the action potential repeatedly along the axon. Because these channels along the axon segment are not constantly opening, depolarization spreads at an optimal speed. The distance between nodes is the optimal distance to keep the membrane depolarized above the threshold at the next node. As Na+ spreads along inside the axon segment’s membrane, the charge dissipates. Nodes any farther down the axon would have depolarization fall off too much for voltage-gated Na+ channels to activate at the next node of Ranvier. Nodes any closer together would have a slower propagation speed. This “jumping” (saltare = “to leap”) of the action potential from one node to the next is called saltatory conduction. Nodes of Ranvier also save energy for the neuron since the channels only need to be present at the nodes and not along the entire axon.

Along with the axon myelination, the axon’s diameter can influence the conduction speed. Similar to water running faster in a wide river than in a narrow creek, Na+-based depolarization spreads faster down a wide axon than a narrow one. This concept is known as resistance. Resistance generally applies to electrical wires or plumbing as much as it does to axons; however, specific conditions vary between electrons or ions and water in a river due to scale.

Self-Check

Learning Activity: Neuron Action Potential

What happens across the membrane of an electrically active cell is a dynamic process that is hard to visualize with static images or through text descriptions. View the animation below to learn more about this process.

- Watch this video “Action Potential – Physiology” (10 min) by Osmosis from Elsevier (2016).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the difference between the driving force for Na+ and K+?

- What is similar about the movement of these two ions?

- Complete the following activity:

Learning Activity: Neuronal Structure

Reinforce your knowledge of the neuronal structure and action potential.

- Label the parts of the axon in areas marked by the lines in Figure 15. Is it myelinated or not?

- Where are the voltage-gated K+ and Na+ channels located?

- Write a figure legend with an appropriate title that incorporates the direction of propagation of the action potential.

- Watch the video “Action Potential in the Neuron” (13:11 min) by Harvard Extension School (2018). Make your own notes, and keep a copy. Attempt to write your own description of the following processes:

This animation demonstrates the behaviour of a typical neuron at its resting membrane potential and when it reaches an action potential and fires, transmitting an electrochemical signal along the axon. It shows how the various components work in concert: Dendrites, cell body, axon, sodium and potassium ions, voltage-gated ion channels, the sodium-potassium pump, and myelin sheaths. It also shows the stages of an action potential: polarization, depolarization, and hyperpolarization.

Disorders of the Nervous Tissue

Several diseases can result from axon demyelination. These diseases do not have the same causes; causes can range from genetics to pathogens to autoimmune disorders. Though the causes vary, the results are largely similar. The myelin insulation of axons is compromised, making electrical signalling slower.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one such disease. It is an autoimmune disease where antibodies produced by lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) mark myelin as something that should not be in the body. This error causes inflammation and myelin destruction in the central nervous system. As the disease destroys insulation around the axons, scarring becomes obvious. This scarring is where the disease’s name comes from; sclerosis means hardening of tissue, which is what a scar is. Multiple scars are found in white matter in the brain and spinal cord. MS symptoms include both somatic and autonomic deficits. Musculature control is compromised, as is control of organs such as the bladder.

Guillain-Barré (pronounced gee-YAN bah-RAY) syndrome is a demyelinating disease affecting the peripheral nervous system. Like MS, it is caused by an autoimmune reaction; however, the inflammation is in peripheral nerves. Sensory symptoms or motor deficits are common, and autonomic failures can lead to changes in the heart rhythm or a drop in blood pressure, especially when standing, which causes dizziness.

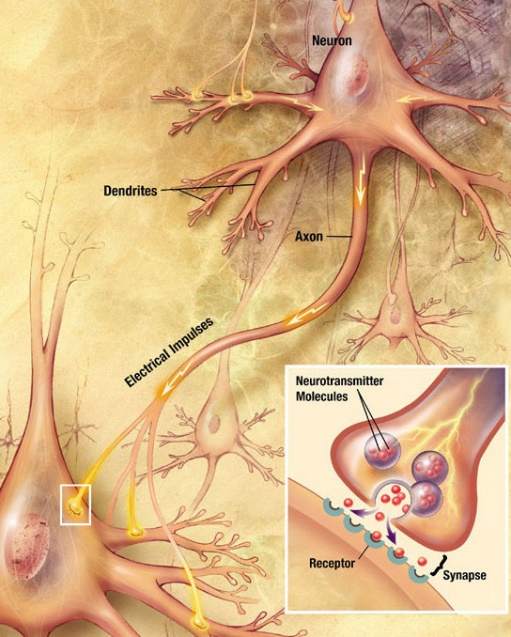

Synaptic Transmission

Communicating information to another neuron requires the action potential to travel along the axon and reach the axon terminals, where it can initiate neurotransmitter release. Transmission from one neuron to another occurs in the synapse. Synapses usually form between axon terminals and dendritic spines, but this is not universally true. There are also axon-to-axon, dendrite-to-dendrite, and axon-to-cell body synapses. The neuron transmitting the signal is called the presynaptic neuron, and the neuron receiving the signal is called the postsynaptic neuron. Note that these designations are relative to a particular synapse. Most neurons are both presynaptic and/or postsynaptic, depending on the location in the neural pathway. There are two types of synapses: chemical and electrical.

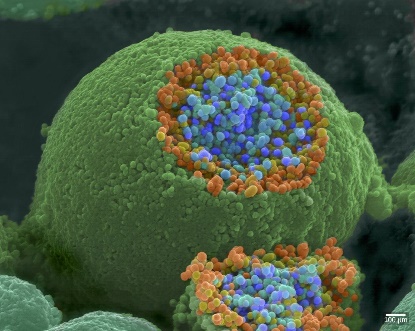

Chemical Synapse

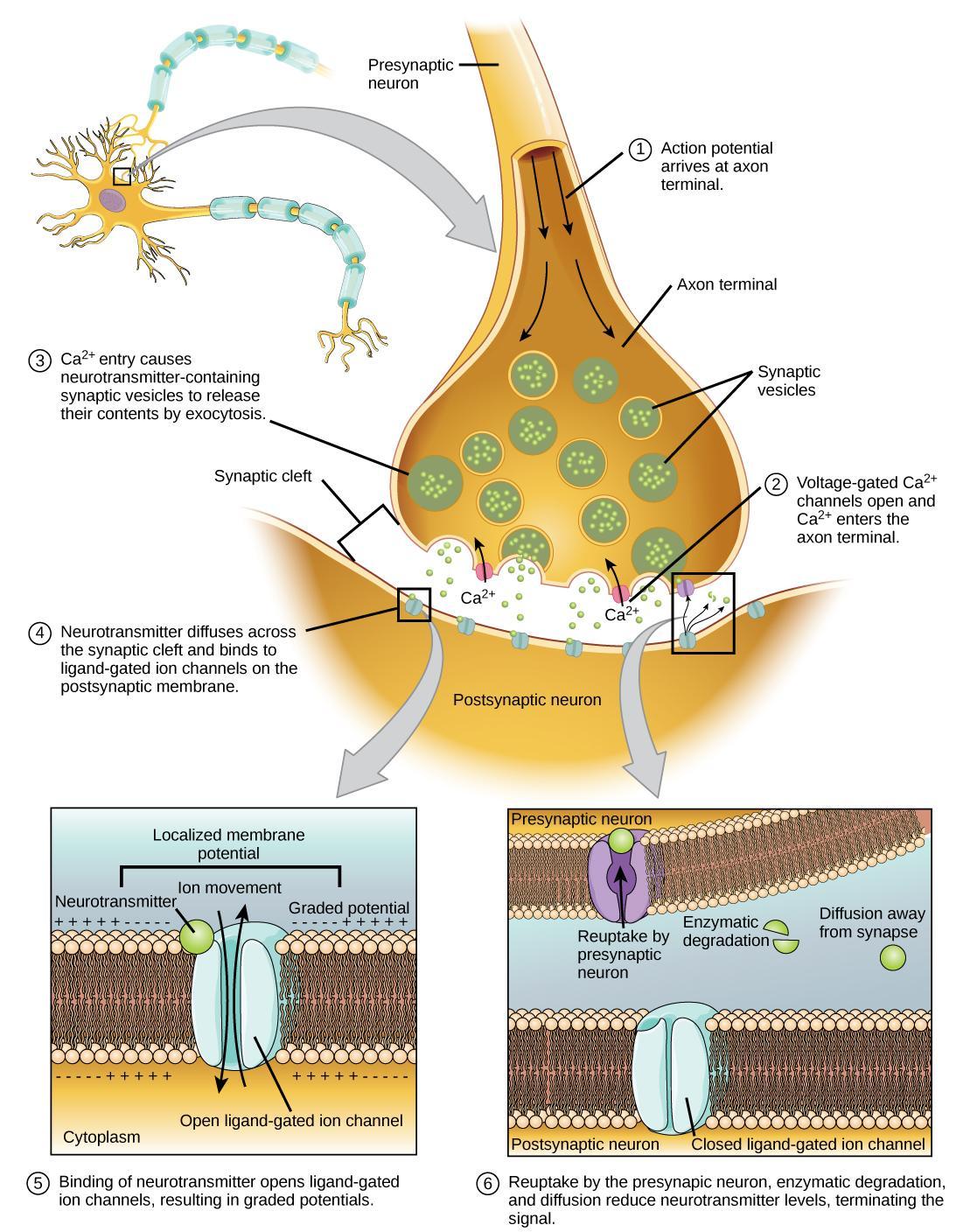

When an action potential reaches the axon terminal, it depolarizes the membrane and opens voltage-gated Na+ channels. Na+ ions enter the cell, further depolarizing the presynaptic membrane. This depolarization causes voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to open. Calcium ions entering the cell initiate a signalling cascade that causes small membrane-bound vesicles, called synaptic vesicles, containing neurotransmitter molecules to fuse with the presynaptic membrane. Figure 16 shows synaptic vesicles using a scanning electron microscope. The axon terminal is spherical, and a sliced-off section reveals small blue and orange vesicles inside.

A vesicle fusing with the presynaptic membrane causes it to release neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. The synaptic cleft is the extracellular space between the presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes (Figure 17). The neurotransmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to receptor proteins on the postsynaptic membrane. In this way, the electrical signal (change in voltage) from the presynaptic neuron converts into a chemical signal (release of neurotransmitter) in the synaptic cleft.

Figure 17 shows the narrow axon of a presynaptic cell widening into a bulb-like axon terminal. A narrow synaptic cleft separates the axon terminal of the presynaptic cell from the postsynaptic cell. In step 1, an action potential arrives at the axon terminal (electrical signal). In step 2, the action potential causes voltage-gated calcium channels in the axon terminal to open, allowing calcium to enter. In step 3, calcium influx causes neurotransmitter-containing synaptic vesicles to fuse with the plasma membrane. The vesicles’ contents are released into the synaptic cleft by exocytosis (chemical signal). In step 4, the neurotransmitter diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds ligand-gated ion channels on the postsynaptic membrane, causing the channels to open. In step 5, the open channels cause ion movement in or out of the cell, resulting in a localized change in membrane potential (electrical signal). In step 6, reuptake by the presynaptic neuron, enzymatic degradation, and diffusion reduce neurotransmitter levels and terminate the signal.

Self-Check

Learning Activity: Synaptic clefts

In this activity, you will review an animation of the synapse, synaptic cleft, release of neurotransmitter and its interaction with receptors, and the ways the neurotransmitter is cleared from the synaptic cleft.

- Watch this video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Synaptic Transmission” (1:51 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2014). Make your own notes, and keep a copy for study purposes.

- Answer the following question:

- Recall the exocytosis steps from Unit 2, Topic 3. How is exocytosis involved in synaptic transmission?

Optional additional resources:

- “The Synapse” (7:08 min) by Bozeman Science (2017).

- “Synapse structure” (6:50 min) by Khan Academy (2014).

Learning Activity: Neurotransmitter Release

The following video describes the mechanisms underlying neurotransmitter release. Calcium influx is thought to play a role in mobilizing and preparing synaptic vesicles for neurotransmitter release.

The hypothesized mechanism by which vesicles fuse with the neuron’s cell membrane to empty their contents into the synaptic cleft reinforces the Unit 2, Topic 3 Learning Objective: Describe the changes that occur to the membrane that result in the action potential, applying the terms polarized, depolarized, and repolarized. Unit 3 will cover additional aspects of membrane fusion.

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Neurotransmitter Release” (2:00 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2018). Make your own notes, and keep a copy for study purposes.

Receptor proteins on the postsynaptic neuron activated by neurotransmitters fall into the following two broad classes:

- Ligand-activated ion channels are membrane-spanning ion channel proteins that open directly in response to ligand binding.

- Metabotropic receptors are not ion channels. Neurotransmitter binding triggers a signalling pathway, which may indirectly open or close channels (or have some other effect entirely).

These two classes are described in more detail below.

Ligand-Activated Ion Channels

The first neurotransmitter receptor class is ligand-activated ion channels, also known as ionotropic receptors. Ionotropic receptors change shape when a neurotransmitter binds, causing the channel to open (Figure 18). This opening may have either an excitatory or an inhibitory effect, depending on the ions that can pass through the channel and their concentrations inside and outside the cell. Ligand-activated ion channels are large protein complexes with certain regions acting as binding sites for the neurotransmitter and others as membrane-spanning segments that make up the channel.

Ligand-activated ion channels typically produce very quick physiological responses. Current starts to flow (ions start to cross the membrane) within tens of microseconds after neurotransmitter binding, and the current stops as soon as the neurotransmitter is no longer bound to its receptors. In most cases, the neurotransmitter is removed from the synapse very rapidly, thanks to enzymes that break it down or neighbouring cells that take it up.

Neurotransmitters can either have excitatory or inhibitory effects on the postsynaptic membrane. For example, a presynaptic neuron releasing acetylcholine at the synapse between a nerve and muscle (called the neuromuscular junction) causes postsynaptic Na+ channels to open. Na+ enters the postsynaptic cell and causes the postsynaptic membrane to depolarize. This depolarization is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) and makes the postsynaptic neuron more likely to fire an action potential. Releasing a neurotransmitter at inhibitory synapses causes inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), hyperpolarizing the presynaptic membrane. For example, when a presynaptic neuron releases the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), GABA binds to and opens Cl– channels. Cl– ions enter the cell and hyperpolarize the membrane, making the neuron less likely to fire an action potential.

Once neurotransmission has occurred, the neurotransmitter must be removed from the synaptic cleft so the postsynaptic membrane can “reset” and be ready to receive another signal. Removing neurotransmitters can occur in three ways: The neurotransmitter diffuses away from the synaptic cleft, enzymes degrade it in the synaptic cleft, or transporter proteins recycle (sometimes called reuptake) it in the presynaptic neuron. Several drugs act at this neurotransmission step. For example, some Alzheimer’s medications inhibit acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that degrades acetylcholine. This enzyme inhibition essentially increases neurotransmission at synapses that release acetylcholine. Once released, the acetylcholine stays in the cleft longer, where it can continually bind and unbind to postsynaptic receptors.

How a neurotransmitter affects a postsynaptic cell mainly depends on the type of receptors it activates, making it possible for a particular neurotransmitter to have different effects on various target cells. A neurotransmitter might excite one set of target cells, inhibit others, and have complex modulatory effects on still others, depending on the type of receptors. However, some neurotransmitters have relatively consistent effects on other cells. Consider the two most widely used neurotransmitters, glutamate and GABA. Glutamate receptors are either excitatory or modulatory in their effects, whereas GABA receptors are all inhibitory in their effects in adults.

Metabotropic Receptors

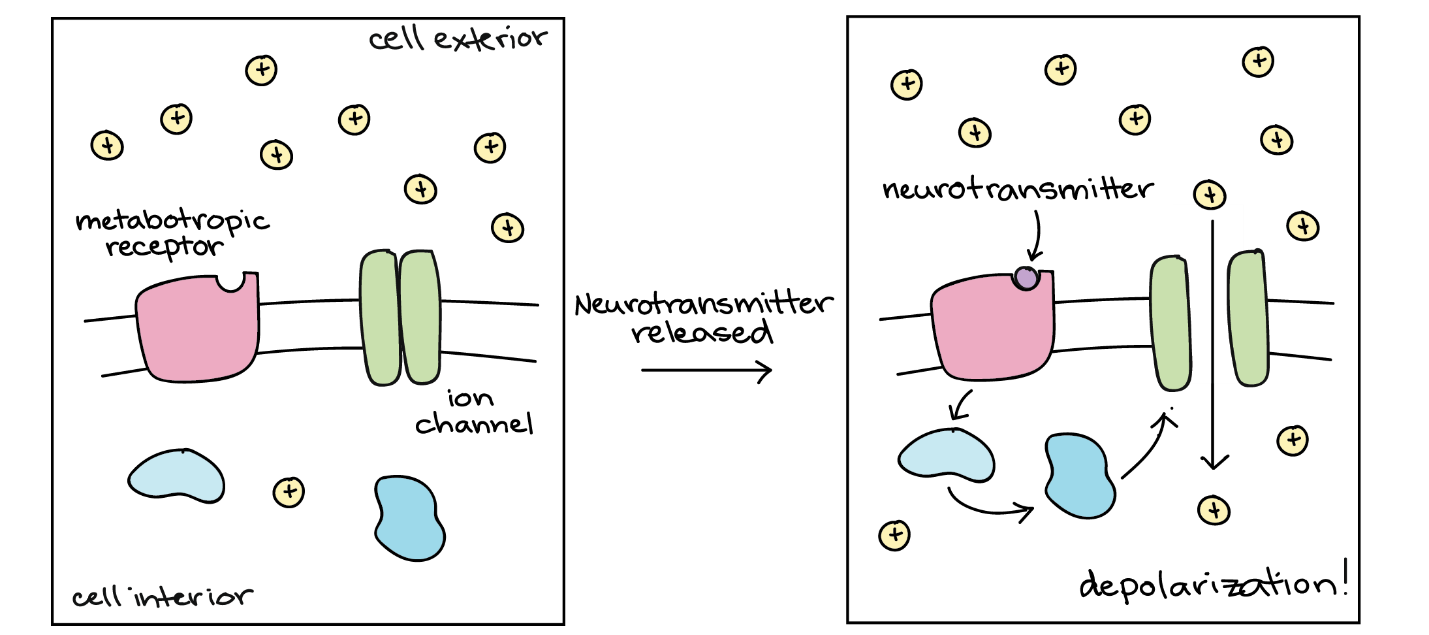

Metabotropic receptors are a neurotransmitter receptor class whose activation only indirectly affects ion channel opening and closing. In this case, the protein to which the neurotransmitter binds — the neurotransmitter receptor — is not an ion channel. Signalling through these metabotropic receptors depends on several molecules activating inside the cell and often involves a second messenger pathway (Figure 19). Because it involves more steps, signalling through metabotropic receptors happens much slower than through ligand-activated ion channels.

Some metabotropic receptors have excitatory effects when activated (make the cell more likely to fire an action potential), while others have inhibitory effects. Often, these effects occur because the metabotropic receptor triggers a signalling pathway that opens or closes an ion channel. Alternatively, a neurotransmitter that binds to a metabotropic receptor may change how the cell responds to a second neurotransmitter acting through a ligand-activated channel. Signalling through metabotropic receptors can also affect the postsynaptic cell that does not involve ion channels at all.

Learning Activity: Neurotransmitter-Receptor Interactions

This activity explores more about acetylcholine, the first neurotransmitter ever discovered. The topics covered in the resources below include the locations of acetylcholine neurons in the brain, acetylcholine receptors, and some functions of acetylcholine. This activity revisits the concept of ligand-receptor interactions, which will continue throughout this course.

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: Acetylcholine” (1:59 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2018). Make your own notes.

- Answer the following questions:

- What type of neurotransmitter is acetylcholine?

- What receptors do acetylcholine act on? What happens after acetylcholine binds to its receptors?

- How is the action of acetylcholine terminated?

- Watch the video “Cone Snail Toxins and Paralysis | HHMI BioInteractive Video” (3:28 min) by BioInteractive (2018) on sea cone snail toxins and paralysis.

- How do these toxins cause muscle paralysis? What did you love learning in this video?

- Watch the video “Calcium Channel Blockers and Paralysis | HHMI BioInteractive Video” (2:30 min) by BioInteractive (2018). This animation shows how the drug Prialt suppresses signals from the nervous system, which can paralyze certain organisms. Prialt was originally derived from the venom of predatory cone snails, which use the venom to paralyze fish, their prey. Provide your own description of how Prialt paralyzes fish.

- Comment on how biological processes occurring in organisms are exploited to aid in human health.

- What did you love learning in this video?

Learning Activity: GABA

The video below discusses the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid, GABA. GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the human nervous system; its effects generally involve making neurons less likely to fire action potentials or release neurotransmitters. GABA acts at both ionotropic (GABAa) and metabotropic (GABAb) receptors, and its action is terminated by a transporter called the GABA transporter. Several drugs, like alcohol and benzodiazepines, cause increased GABA activity, which is associated with sedative effects.

- Watch the video “2-Minute Neuroscience: GABA” (1:59 min) by Neuroscientifically Challenged (2018). Make your own notes.

- Answer the following question:

How does GABA inhibit synaptic transmission? - For extra practice, please visit the Biology Corner’s “The Anatomy of a Synapse” webpage (Muskopf [date unknown]) and complete the exercises.

Electrical Synapse

While electrical synapses are fewer in number than chemical synapses, they are found in all nervous systems where they play important and unique roles. Neurotransmission in electrical synapses is quite different from that in chemical synapses. In an electrical synapse, the presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes sit very close together; they connect physically via channel proteins, forming gap junctions. Gap junctions allow current to pass directly from one cell to the next.

There are key differences between chemical and electrical synapses. Because chemical synapses depend on neurotransmitter molecules being released from synaptic vesicles to pass on their signal, there is an approximately one-millisecond delay between when the axon potential reaches the presynaptic terminal and when the neurotransmitter causes the postsynaptic ion channels to open. Additionally, this signalling is unidirectional. In contrast, signalling in electrical synapses is virtually instantaneous, which is important for synapses involved in key reflexes, and some electrical synapses are bidirectional. Electrical synapses are also more reliable as they are less likely to be blocked. Furthermore, they are important for synchronizing the electrical activity in a group of neurons. For example, recent research suggests electrical synapses in the thalamus regulate slow-wave sleep; disrupting these synapses can cause seizures.

A neuron stimulates muscle contraction by sending signals across the neuromuscular junction, or the point of contact between a neuron and a muscle cell. The signalling process begins when membrane-bound structures inside the neuron fuse with the cell membrane, releasing signalling molecules into the neuromuscular junction. These molecules then diffuse through the junction and bind to receptors on the surface of the muscle cell, leading to muscle contraction.

One good way to learn about this process is to understand what happens when it goes wrong. Botulism is a rare illness caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. This toxin, called botulinum toxin, inhibits the process that releases signalling molecules from neurons at the neuromuscular junction. Specifically, it disrupts the ability of neurotransmitter vesicles to fuse with the membrane. This disruption affects the neuron-muscle cell signalling pathway, resulting in temporary paralysis. Botulinum toxin is the major ingredient in Botox used in cosmetic procedures. Unit 3 will explore membrane fusion mechanisms further.

Brain-Computer Interface

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also called Lou Gehrig’s Disease) is a neurological disease characterized by degeneration in motor neurons that control voluntary movements. The disease begins with muscle weakening and a lack of coordination. Eventually, it destroys the neurons that control speech, breathing, and swallowing; in the end, the disease can lead to paralysis. At that point, patients require assistance from machines to breathe and communicate. Several special technologies have been developed to allow “locked-in” patients to communicate with the rest of the world. For example, one technology allows patients to twitch their cheek to type out sentences. These sentences can then be read aloud by a computer.

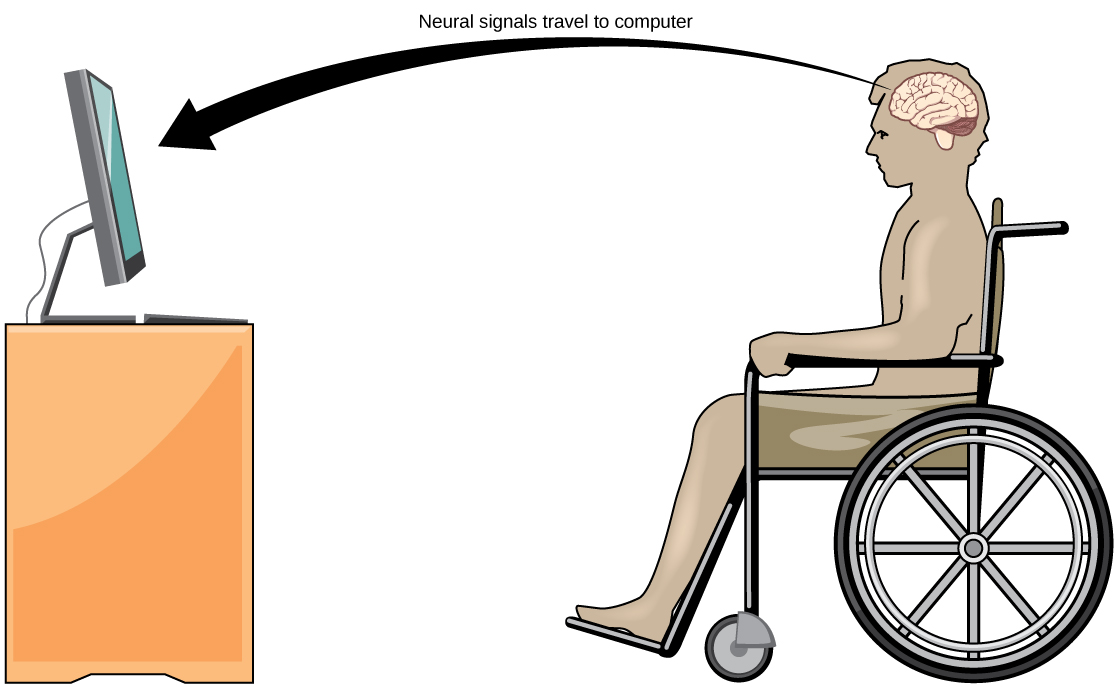

A relatively new line of research for helping paralyzed patients, including those with ALS, communicate and retain a degree of self-sufficiency is called brain-computer interface (BCI) technology (illustrated in Figure 20). This technology sounds like something out of science fiction in that it allows paralyzed patients to control a computer using only their thoughts. BCI comes in several forms. Some forms use electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings from electrodes taped onto the skull. These recordings contain information from large neuron populations that a computer can decode. Other BCI forms require implanting an array of electrodes smaller than a postage stamp in the arm and hand area in the motor cortex. This BCI form, while more invasive, is very powerful as each electrode can record actual action potentials from one or more neurons. These electrodes send the signals to a computer trained to decode the signal and feed it to a tool, such as a cursor on a computer screen. As a result, a patient with ALS can use e-mail and the internet while also communicating with others by thinking about moving their hand or arm (even though the paralyzed patient cannot make that bodily movement). Recent advances have allowed a paralyzed locked-in patient who suffered a stroke 15 years ago to control a robotic arm and even feed herself coffee using BCI technology.

Despite the amazing advancements in BCI technology, it also has limitations. The technology can require many hours of training and long periods of intense concentration for the patient; it can also require brain surgery to implant the devices.

Learning Activity: Neural Control

Cathy Hutchinson has been unable to move her own arms or legs for 15 years. However, using the most advanced brain-machine interface ever developed, she can steer a robotic arm towards a bottle, pick it up, and drink her morning coffee. The interface includes a sensor implanted in Cathy’s brain, which ‘reads’ her thoughts, and a decoder, which turns her thoughts into instructions for the robotic arm. Watch the video below to see Cathy control the arm and hear from the team behind the pioneering study.

The original research paper is “Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm” by Hochberg et al. (2012).

- Watch the video “Paralysed woman moves robot with her mind – by Nature Video” (4:29 min) by Nature Video (2012), where Cathy Hutchinson uses a sophisticated brain-machine interface to move a robot arm.

Learning Activity: Electrical Activity in Neurons

Part 1

Neurons encode information with electrical signals, such as action potentials. They transmit that information to other neurons through synapses. This HHMI Click & Learn activity describes these processes in more detail, shows how they can be measured using microelectrodes, and displays experimental results using neuron potential or voltage graphs.

The interactive will show how single cultured sensory neurons from Aplysia measure electrical activity. It will also introduce you to the transmission of action potentials from sensory to motor neurons. This knowledge will also help you to complete the experimental section of the Unit 2 Assignment.

- Visit the “Electrical Activity of Neurons” interactive simulation by BioInteractive (2008). Click on the “Start Interactive” button. Progress through various aspects to measure neuronal activity at your own pace.

Make sure to watch the short video clips of researchers describing the transmission of electrical impulses, recording the voltage after stimulation of action potentials, stimulation of a motor neuron by a sensory neuron, and the effects of serotonin on the strength of synaptic connections.

- Answer the following questions, and document your work for later.

- What is the name of the device used to measure the electrical activity of a neuron? Why is it easier to use this device using Aplysia?

- Describe the graph used to visualize neuronal activity.

- Why is an electrode placed on the sensory neuron? What does it take the place of?

- How does the voltage of the cell change after electrode stimulation?

- Why does it take multiple stimulations of the neuron in the movie on page 5?

Part 2

This next HHMI interactive modular lab explores techniques for identifying and recording the electrical activities of neurons, using the leech as a model organism. Therefore, it will build on the knowledge you learned from the first Click & Learn activity you just completed.

In this lab, you will investigate and map how neurons in the leech’s nervous system respond to different touch sensations. The lab includes sections on dissecting a leech specimen, measuring the voltage (potential) of a neuron responding to various stimuli, and injecting fluorescent dyes into neurons to visualize their morphology. You will engage in key science practices, including collecting data and interpreting graphs, using appropriate controls and identifying individual neurons based on the results.

The lab contains an interactive lab space, an informational notebook, and embedded questions. It also includes supplementary resources, such as background on the anatomy of a neuron, a review of the resting and action potential, and a glossary of scientific terms. This activity will reinforce your knowledge of cell culture and fluorescence microscopy learned in Unit 1, Topic 4. This knowledge will help you to complete the Unit 2 Assignment.

- Visit BioInteractive’s “Neurophysiology Virtual Lab” interactive simulation by BioInteractive (1997) and click on the “Start Interactive” button. Scroll through the “Click & Learn” section to familiarize yourself with the site.

- Click through all three tabs, including ‘Neurophysiology Virtual Lab,’ ‘Leech Dissection,’ and ‘Probe & Identify.’

- Click on ‘Background’ at any time to refresh your knowledge.

- Probe each neuronal type to generate your data.

- Once complete, click ‘Conclusion’ and then ‘Report’ to view your data.

- Do not forget to document your work for later. Print or screenshot your report to document your work.

Learning Activity: Neural Transmission

This activity will help you reinforce your knowledge from the readings about neural transmission and integral membrane proteins.

Using proper terminology, try to answer each of the following without looking up the answers. Then, fill in any missing details by reviewing the Unit 2, Topic 4 readings.

- Define nerve impulse.

- What is the resting potential of a neuron, and how is it maintained?

- Explain how and why an action potential occurs.

- Outline how a signal is transmitted from a presynaptic cell to a postsynaptic cell at a chemical synapse.

- What generally determines the effects of a neurotransmitter on a postsynaptic cell?

- Identify three general types of effects that neurotransmitters may have on postsynaptic cells.

- Explain how an electrical signal in a presynaptic neuron causes chemical signal transmission at the synapse.

- The flow of which type of ion into a neuron results in an action potential? How do these ions get into the cell? What does this flow of ions do to the relative charge inside the neuron compared to the outside?

- Name two neurotransmitters. What is the difference between an electrical and chemical synapse?

- Figure 21 shows how an action potential transmits a signal across a synapse to another cell by neurotransmitter molecules. The inset diagram shows in detail the structures and processes occurring at a single-axon terminal and synapse.

- Write your own figure legend to describe this process. Labelling the figure may be helpful.

- Use a red pen and place arrows that illustrate the direction of a nerve impulse between the two neurons.

Figure 21: How an action potential transmits a signal across a synapse to another cell by neurotransmitter molecules. The inset diagram shows in detail the structures and processes occurring at a single axon terminal and synapse. (US National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging 2010/Wikimedia Commons) Public domain

Learning Activity: Myelinated Neuron Model

Being able to create a visual representation of complex nervous systems is important for describing/explaining how these systems detect external and internal signals, transmit and integrate information, and produce responses.

- Create a myelinated neuron model using any suitable items (e.g., household or dollar store). Do not forget to document your work for later.

- Take a picture of your model and/or make a video explaining the parts and chemical transmission.

Learning Activity: Visualizing Neuronal Activity

In neurons, action potentials induce neurotransmitter release at axon terminals by opening voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, allowing for Ca2+ influx. As a result, GCaMP is commonly used to measure increases in intracellular Ca2+ in neurons as a proxy for neuronal activity in multiple animal models, including Caenorhabditis elegans, zebrafish, Drosophila melanogaster, and mice. GCaMP has played a vital role in establishing large-scale neural recordings in animals to investigate how activity patterns in neuronal networks influence behaviour. For example, Nguyen et al. (2016) used GCaMP in whole-brain imaging during free movement of C. elegans to identify neurons and groups of neurons whose activity correlated with specific locomotor behaviours.1

GCaMP is a genetically encoded calcium indicator (GECI) initially developed in 2001 by Junichi Nakai.2,3,4 It is a synthetic fusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP), calmodulin (CaM), and M13, a peptide sequence from myosin light-chain kinase.5 When bound to Ca2+, GCaMP fluoresces green with a peak excitation wavelength of 480 nm and a peak emission wavelength of 510 nm.6 It is used in biological research to measure intracellular Ca2+ levels both in vitro and in vivo using virally transfected or transgenic cell and animal lines.

This animation shows how the calcium imaging technique can be used to observe neuronal activity and associate behavioural characterizations with physiological states. This technique requires a genetically engineered calcium indicator and visual detection using a fluorescent microscope. This knowledge will help you to complete the Unit 2 Assignment.

- Go to LabXchange and view “Visualizing Neuronal Activity via Calcium Signaling” (4:22 min) by Life Sciences Outreach Program at Harvard University (2020). Make your own notes and vocabulary list.

- In your own words, write the hypothesis and prediction of the experiment describing Ca2+ imaging to detect how AWC neurons respond to an attractive odorant.

- Explain whether the experimental results support your hypothesis. Write a conclusion based on the evidence about how AWC-off neurons respond to odorants. How was Ca2+ imaging essential in this experiment?

Key Concepts and Summary

The nervous system is characterized by electrical signals sent from one area to another. Whether those areas are close or very far apart, the signal must travel along an axon. The basis of the electrical signal is controlled ion distribution across the membrane. Transmembrane ion channels regulate when ions can move in or out of the cell to generate a precise signal. This signal is the action potential, which has a very characteristic shape based on voltage changes across the membrane in a given time period.

Neurons have charged membranes because there are different ion concentrations inside and outside the cell. Voltage-gated ion channels control ions moving in and out of a neuron. An action potential fires when the depolarization of the neuronal membrane reaches at least the threshold of excitation. The membrane is normally at rest with established Na+ and K+ concentrations on either side. A stimulus will start membrane depolarization, and voltage-gated channels cause further depolarization followed by membrane repolarization. A slight overshoot of hyperpolarization marks the end of the action potential. While an action potential is in progress, the same conditions cannot generate another. An inactivated voltage-gated Na+ channel prevents the generation of any action potentials. Once that channel returns to its resting state, a new action potential is possible, but a relatively stronger stimulus must start it to overcome the K+ leaving the cell.

As the action potential travels down the axon, the spreading depolarization opens voltage-gated ion channels. In unmyelinated axons, this happens in a continuous fashion because there are voltage-gated channels throughout the membrane. In myelinated axons, propagation is described as saltatory because voltage-gated channels are only found at the nodes of Ranvier and the electrical events seem to “jump” from one node to the next. Saltatory conduction is faster than continuous conduction, meaning that myelinated axons propagate their signals faster. The axon’s diameter also makes a difference as ions diffusing within the cell have less resistance in a wider space.

The action potential propagates along a myelinated axon to the axon terminals. Synapses are the contacts between neurons with either a chemical or electrical nature. Chemical synapses are far more common. In a chemical synapse, the action potential causes neurotransmitter molecules to release into the synaptic cleft. Neurotransmitters binding to postsynaptic receptors can cause excitatory or inhibitory postsynaptic potentials by depolarizing or hyperpolarizing, respectively, the postsynaptic membrane. In electrical synapses, the action potential communicates directly to the postsynaptic cell through gap junctions, which are large channel proteins connecting the pre- and postsynaptic membranes. Synapses are not static structures and can be strengthened and weakened.

- A nerve impulse is an electrical phenomenon occurring from a difference in electrical charge across the plasma membrane of a neuron.

- The sodium-potassium pump maintains an electrical gradient across a neuron’s plasma membrane when it is not actively transmitting a nerve impulse. This gradient is called the resting potential of the neuron.

- An action potential is a sudden reversal of the electrical gradient across a neuron’s plasma membrane. It begins when the neuron receives a chemical signal from another cell or some other type of stimulus. The action potential travels rapidly down the neuron’s axon as an electric current. It occurs in three stages: Depolarization, Repolarization and Recovery.

- A nerve impulse transmits to another cell at either an electrical or chemical synapse. At a chemical synapse, the presynaptic cell releases the neurotransmitter chemicals into the synaptic cleft between cells. These chemicals travel across the cleft to the postsynaptic cell and bind to receptors embedded in its membrane.

- Neurotransmitters come in many different types. Their effects on the postsynaptic cell generally depend on the type of receptor they bind to. The effects may be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory in more complex ways. The neurotransmitter must be inactivated or removed from the synaptic cleft so that the stimulus is limited in time. Both physical and mental disorders may occur if there are problems with neurotransmitters or their receptors.

An example of a chemical synapse is the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). In the nervous system, there are many more synapses that are essentially the same as the NMJ. Synapses have common characteristics summarized in the following list:

- presynaptic element

- neurotransmitter (packaged in vesicles)

- synaptic cleft

- receptor proteins

- postsynaptic element

- neurotransmitter elimination or re-uptake

For the NMJ, these characteristics are as follows:

- the presynaptic element is the motor neuron’s axon terminals

- the neurotransmitter is acetylcholine

- the synaptic cleft is the space between the cells where the neurotransmitter diffuses

- the receptor protein is the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- the postsynaptic element is the sarcolemma of the muscle cell

- the neurotransmitter is eliminated by acetylcholinesterase.

Other synapses are similar to this, with different specifics, but all contain the same characteristics.

Quiz

Complete the Unit 2 Quiz found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Assignment

Complete the Unit 2 Assignment found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Key Terms

time during an action period when another action potential cannot be generated because the voltage-gated Na+ channel is inactivated

neurotransmitter released by neurons in the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system

change in voltage of a cell membrane in response to a stimulus that results in transmission of an electrical signal; unique to neurons and muscle fibers

part of the voltage-gated Na+ channel that opens when the membrane voltage reaches threshold

single process of the neuron that carries an electrical signal (action potential) away from the cell body toward a target cell

tapering of the neuron cell body that gives rise to the axon

single stretch of the axon insulated by myelin and bounded by nodes of Ranvier at either end (except for the first, which is after the initial segment, and the last, which is followed by the axon terminal)

end of the axon, where there are usually several branches extending toward and that can synapse with the target cell

cytoplasm of an axon, which is different in composition than the cytoplasm of the neuronal cell body

connection between two neurons, or between a neuron and its target, where a neurotransmitter diffuses across a very short distance

neurotransmitter system of acetylcholine, which includes its receptors and the enzyme acetylcholinesterase

slow propagation of an action potential along an unmyelinated axon owing to voltage-gated Na+ channels located along the entire length of the cell membrane

one of many branchlike processes that extends from the neuron cell body and functions as a contact for incoming signals (synapses) from other neurons or sensory cells

change in a cell membrane potential from rest toward zero

connection between two neurons, or any two electrically active cells, where ions flow directly through channels spanning their adjacent cell membranes

principle of selectively allowing ions through a channel based on their charge

excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP)

graded potential in the postsynaptic membrane that is the result of depolarization and makes an action potential more likely to occur

property of a channel that determines how it opens under specific conditions, such as voltage change or physical deformation

change in the membrane potential that varies in size, depending on the size of the stimulus that elicits it

part of a voltage-gated Na+ channel that closes when the membrane potential reaches +30 mV

inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP)

graded potential in the postsynaptic membrane that is the result of hyperpolarization and makes an action potential less likely to occur

first part of the axon as it emerges from the axon hillock, where the electrical signals known as action potentials are generated

neurotransmitter receptor that acts as an ion channel gate, and opens by the binding of the neurotransmitter

ion channel that opens randomly and is not gated to a specific event, also known as a non-gated channel

another name for an ionotropic receptor for which a neurotransmitter is the ligand

ion channel that opens when a physical event directly affects the structure of the protein

distribution of charge across the cell membrane, based on the charges of ions

lipid-rich insulating substance surrounding the axons of many neurons, allowing for faster transmission of electrical signals

lipid-rich layer of insulation that surrounds an axon, formed by oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system; facilitates the transmission of electrical signals

cord-like bundle of axons located in the peripheral nervous system that transmits sensory input and response output to and from the central nervous system

neural tissue cell that is primarily responsible for generating and propagating electrical signals into, within, and out of the nervous system

chemical signal that is released from the synaptic end bulb of a neuron to cause a change in the target cell

gaps in the myelin sheath where the signal is recharged

channel that is not specific to one ion over another, such as a nonspecific cation channel that allows any positively charged ion across the membrane

glial cell that myelinates central nervous system neuron axons

in cells, an extension of a cell body; in the case of neurons, this includes the axon and dendrites

movement of an action potential along the length of an axon

time after the initiation of an action potential when another action potential cannot be generated

time during the refractory period when a new action potential can only be initiated by a stronger stimulus than the current action potential because voltage-gated K+ channels are not closed

return of the membrane potential to its normally negative voltage at the end of the action potential

property of an axon that relates to the ability of particles to diffuse through the cytoplasm; this is inversely proportional to the fiber diameter

nervous system function that causes a target tissue (muscle or gland) to produce an event as a consequence to stimuli

the difference in voltage measured across a cell membrane under steady-state conditions, typically -70 mV

quick propagation of the action potential along a myelinated axon owing to voltage-gated Na+ channels being present only at the nodes of Ranvier

glial cell that creates myelin sheath around a peripheral nervous system neuron axon

principle of selectively allowing ions through a channel on the basis of their relative size

in neurons, that portion of the cell that contains the nucleus; the cell body, as opposed to the cell processes (axons and dendrites)

process of multiple presynaptic inputs creating EPSPs around the same time for the postsynaptic neuron to be sufficiently depolarized to fire an action potential

narrow junction across which a chemical signal passes from neuron to the next, initiating a new electrical signal in the target cell

small gap between cells in a chemical synapse where neurotransmitter diffuses from the presynaptic element to the postsynaptic element

swelling at the end of an axon where neurotransmitter molecules are released onto a target cell across a synapse

spherical structure that contains a neurotransmitter

a part of a cell, often a protein, that is sensitive to changes in temperature

membrane voltage at which an action potential is initiated

ion channel that opens because of a change in the charge distributed across the membrane where it is located

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Lightning near body of water and rock formation by Jeremy Bishop (2016), via Unsplash, is used under the Unsplash license.

- Figure 2: Figure 12.17 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 12.18 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 12.19 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 12.20 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 12.21 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 12.22 from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 8-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 8-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 8-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: Parts of a Neuron from OpenStaxCollege Anatomy & Physiology (OpenStaxCollege 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: The Process of Myelination from OpenStaxCollege Anatomy & Physiology (OpenStaxCollege 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 26.13 from OpenStax Biology for AP® Courses (Zedalis and Eggebrecht 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: Propagation of action potential along myelinated nerve fiber en by Helixitta (2015), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Neuron Hand-tuned by Quasar Jarosz (2009), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 16: Figure 26.14 from OpenStax Biology for AP® Courses (Zedalis and Eggebrecht 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 17: Figure 26.15 from OpenStax Biology for AP® Courses (Zedalis and Eggebrecht 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 18: Ligand-activated ion channels by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 19: Metabotropic receptors by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 20: Figure 26.17 from OpenStax Biology for AP® Courses (Zedalis and Eggebrecht 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 21: Chemical synapse schema cropped by US National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (2010), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain. https://web.archive.org/web/20070713113018/http://www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers/Publications/UnravelingTheMystery/Part1/NeuronsAndTheirJobs.htm

References

6 Barnett LM, Hughes TE, Drobizhev M. 2017. Deciphering the molecular mechanism responsible for GCaMP6m’s Ca2+-dependent change in fluorescence. PLOS One. 12(2):e0170934. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0170934. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170934.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2013. Anatomy and physiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/preface.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2013. Anatomy and physiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 12.4: action potential. Figures 12.17 to 12.22. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/12-4-the-action-potential.

BioInteractive. 1997. Neurophysiology virtual lab [interactive simulation]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.biointeractive.org/classroom-resources/neurophysiology-virtual-lab.

BioInteractive. 2008. Electrical activity of neurons [interactive simulation]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.biointeractive.org/classroom-resources/electrical-activity-neurons.

BioInteractive. Calcium channel blockers and paralysis | HHMI BioInteractive video [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Nov 15, 2:30 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0VT7t8i80Y.

BioInteractive. Cone snail toxins and paralysis | HHMI BioInteractive video [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Nov 15, 3:28 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B4QlPnzHqGg.

Bishop J. 2016. Lightning near body of water and rock formation [Image]. Dee Why (Australia): Unsplash. [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://unsplash.com/photos/lightning-near-body-of-water-and-rock-formation-td7G4W1HSIE.

Bozeman Science. The synapse [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Feb 6, 7:08 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L41TYxYUqqs.

5 Chen T-W, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V. 2013. Nature. 499:295-300. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature12354. doi:10.1083/nature12354.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Chapter 36.1: sensory processes. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/36-1-sensory-processes.

CNX OpenStax. 2016. Figure 35 02 04. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2016 Jul 5; accessed 2022 Jul 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figure_35_02_04.png.

4 Dana H, Sun Y, Mohar B, Hulse BK, Kerlin AM, Hasseman JP, Tsegaye G, Tsang A, Wong A, Patel R, et al. 2019. High-performance calcium sensors for imaging activity in neuronal populations and microcompartments. Nat Methods. 16:649-657. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41592-019-0435-6. doi:10.1038/s41592-019-0435-6.

Harvard Extension School. Action potential in the neuron [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Mar 26, 13:11 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oa6rvUJlg7o.