1.4 Cell Culture

The Immortal Cell Line of Henrietta Lacks

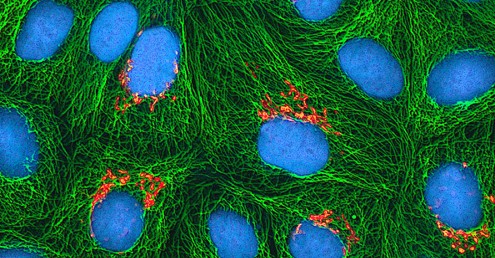

In January 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a 30-year-old African American woman from Baltimore, was diagnosed with cervical cancer at John Hopkins Hospital. Scientists now know that human papillomavirus (HPV) caused her cancer. Cytopathic effects of the virus altered the characteristics of her cells in a process called transformation, which gives the cells the ability to divide continuously. This ability, of course, resulted in a cancerous tumour that eventually killed Mrs. Lacks in October at age 31. Before her death, samples of her cancerous cells were taken without her knowledge or permission. The samples eventually ended up in the possession of Dr. George Gey, a biomedical researcher at Johns Hopkins University. Gey managed to grow some of the cells from Lacks’ sample, creating what is known today as the immortal HeLa cell line (a population of cells descended from a single cell and containing the same genetic makeup) (Figure 1). These cells can live and grow indefinitely and, even today, are still widely used in many research areas.

According to Lacks’s husband, neither Henrietta nor the family gave the hospital permission to collect her tissue specimen. Indeed, the family was not aware until 20 years after Lacks’s death that her cells were still alive and actively being used for commercial and research purposes. Yet HeLa cells have been pivotal in numerous research discoveries related to polio, cancer, and AIDS, among other diseases. The cells have also been commercialized, although they have never themselves been patented. Despite this, Henrietta Lacks’s estate has never benefited from the use of the cells; however, in 2013, the Lacks family was given control over the publication of the genetic sequence of her cells.

This case raises several bioethical issues surrounding patients’ informed consent and the right to know. When Lacks’s tissues were taken, there were no laws or guidelines about informed consent. Does that mean she was treated fairly at the time? By today’s standards, the answer would be no. Harvesting tissue or organs from a dying patient without consent is not only considered unethical but illegal, regardless of whether such an act could save other patients’ lives. Then, is it ethical for scientists to continue to use Lacks’s tissues for research, even though they were obtained illegally by today’s standards?

Ethical or not, Lacks’s cells are widely used today for so many applications that it is impossible to list them all. Is this a case in which the ends justify the means? Would Lacks be pleased to know about her contribution to science and the millions of people who have benefited? Would she want her family compensated for the commercial products developed using her cells? Or would she feel violated and exploited by the researchers who took part of her body without her consent? Because no one asked her, no one will ever know.

Unit 1, Topic 4 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 1, Topic 4, you will be able to:

- Understand the basics of cell culture, including aseptic technique and subculturing.

- Describe why most primary cell cultures cannot divide indefinitely.

- Access and utilize scientific resources to design and carry out your own cell culture experiment.

- Reflect on ethics in research and recognise the importance of Henrietta Lacks and HeLa cells.

- Describe the pros and cons of both primary and continuous/established cells in research.

| Unit 1, Topic 4—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 1, Topic 4 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell Cultures. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Henrietta Lacks. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Telomere Replication. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Telomeres. | 25 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 1 Quiz. | 8 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 1 Assignment. | 100 |

Cell and Tissue Culture

Scientists have developed a number of model systems to study cellular processes directly in living cells and organisms. Researchers also culture (grow) living cells outside the organism of origin in a Petri dish (in vitro) containing proper conditions such as nutrients, temperature and density. These conditions vary for each cell type but generally consist of a suitable vessel with a substrate or medium that supplies the essential nutrients (amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals), growth factors, hormones, and gases (CO2 and O2), and regulates the physiochemical environment (pH buffer, osmotic pressure, and temperature). The results obtained from cultured cells may not reflect what happens within an intact organism. Nevertheless, researchers use cell cultures to study many biological processes, including cancer, viral function, protein function, cellular differentiation, gene regulation and viability.

Cell culture has been practiced since the late 1800s, but it did not become popular until the early 50s with the dissemination of cells biopsied from the cervical cancer of Mrs. Henrietta Lacks. Her cells became known as HeLa and are the oldest and most commonly used immortal human cell line used in scientific research. The successful culture of HeLa cells has led to many important medical discoveries and vaccines, such as the vaccine for polio.

A primary cell culture is freshly prepared from animal organs or tissues. Cells are extracted from tissues by mechanical scraping or mincing to release cells or by an enzymatic method using trypsin or collagenase to break up tissue and release single cells into suspension. Because of anchorage-dependence requirements, primary cell cultures require a liquid culture medium in a Petri dish or tissue-culture flask, so cells have a solid surface such as glass or plastic for attachment and growth.

Learning Activity: Cell Cultures

- Watch the video “Cell Culture Tutorial – An Introduction” (7:43 min) by Applied Biological Materials – abm (2015) to get an overview of various aspects of culturing cells. Make your own notes.

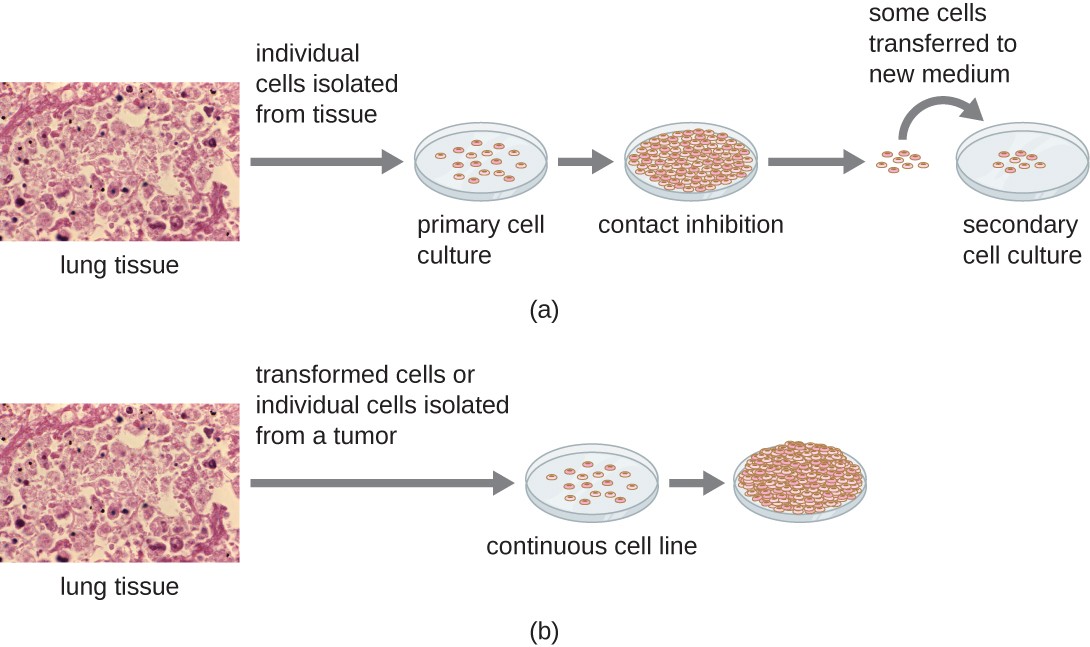

Primary cultures usually have a limited life span. When cells in a primary culture undergo mitosis and a sufficient density of cells is produced, cells come in contact with other cells (Figure 2a). When this cell-to-cell contact occurs, mitosis is triggered to stop. This reaction is known as contact inhibition, and it prevents the density of the cells from becoming too high. When a culture experiences contact inhibition, it is said to be confluent. Preventing contact inhibition involves transferring cells from the primary cell culture to another vessel with a fresh growth medium (i.e., subcultured). This new culture is called a secondary cell culture. Periodically, cell density must be reduced by pouring off some cells and adding fresh medium to provide space and nutrients to maintain cell growth.

In contrast to primary cell cultures, continuous cell lines, usually derived from transformed cells or tumours, are often able to be subcultured many times or even grown indefinitely (in which case they are called immortal). Subculturing is also known as passaging cells, which involves removing the medium and transferring cells from a previous culture into a fresh growth medium. Subculturing is used to prolong the life and/or expand the number of cells or microorganisms in the culture. Continuous cell lines may not exhibit anchorage dependency (they will grow in suspension) and may have lost their contact inhibition. As a result, continuous or established cell lines can grow in piles or lumps resembling small tumour growths (Figure 2b). Nevertheless, primary cells are of value because they are closer to the physical environment of a particular organism. Results from continuous/established cells lines must consider that they originate from a cancerous environment.

HeLa cells were the first continuous, cultured cell line and were used to establish cell/tissue culture as an important technology for researching cell biology, virology, and medicine. Before discovering HeLa cells, scientists could not establish tissue or cell cultures with any reliability or stability. After more than six decades, this cell line is still alive and used for medical research.

Learning Activity: Henrietta Lacks

Imagine something small enough to float on a particle of dust that holds the keys to understanding cancer, virology, and genetics. Luckily for us, such a thing exists in the form of trillions upon trillions of human, lab-grown cells called HeLa. But where did we get these cells? Robin Bulleri tells the story of Henrietta Lacks, a woman whose DNA led to countless cures, patents, and discoveries.

- Watch the video “The immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks – Robin Bulleri” (4:26 min) by TED-Ed (2016).

Answer the following questions:

- What type of cancer killed Henrietta Lacks?

- Colon

- Cervical

- Lung

- Brain

Show/Hide answer.

b. Cervical

- Why do scientists need to be able to study cells in a laboratory environment?

- So they will not endanger patients’ lives

- So they can repeat experiments

- Because they need a large supply of identical cells

- All of the other answers are correct

Show/Hide answer.

d. All of the other answers are correct

- How do HeLa cells keep dividing while other cells die off?

- HeLa ignores signals to stop dividing

- HeLa ignores mutations that accumulate over generations

- HeLa avoids apoptosis

- All of the above

Show/Hide answer.

a. HeLa ignore signals to stop dividing

- Research with HeLa cells led to a vaccine for _, which likely caused Henrietta’s cancer.

- Polio

- HPV

- Mumps

- HIV

Show/Hide answer.

b. HPV

- Open-ended question: Dr. Gey took a sample of the tumour cells from Henrietta Lacks without her or her family’s permission. He then gave away samples of HeLa cells to labs all over the world. While Dr. Gey did not profit from HeLa, the Lacks family was completely unaware of Henrietta’s contributions to science for decades. Do you think what Dr. Gey did was ethical, and do you think this type of situation would happen today? Why or why not?

How Can HeLa Cells Grow Indefinitely? —Telomeres, Aging and Disease

With the exception of some derived from tumours, most primary cell cultures have a limited lifespan. The lifespan of most cells is genetically determined, but some cell-culturing cells have been “transformed” into immortal cells, which indefinitely reproduce if provided with optimal conditions. Many human cells divide 50-60 times in culture and then self-destruct. This is known as the Hayflick limit, or Hayflick phenomenon, and it is the number of times a normal somatic, differentiated human cell population will divide before cell division stops. However, this limit does not apply to stem cells or HeLa cells. Read on to find out why.

The End-Replication Problem

Unlike bacterial chromosomes, the chromosomes of eukaryotes are linear (rod-shaped), meaning that they have ends. These ends pose a problem for DNA replication. The DNA at the very end of the chromosome cannot be fully copied in each round of replication, resulting in a slow, gradual shortening of the chromosome.

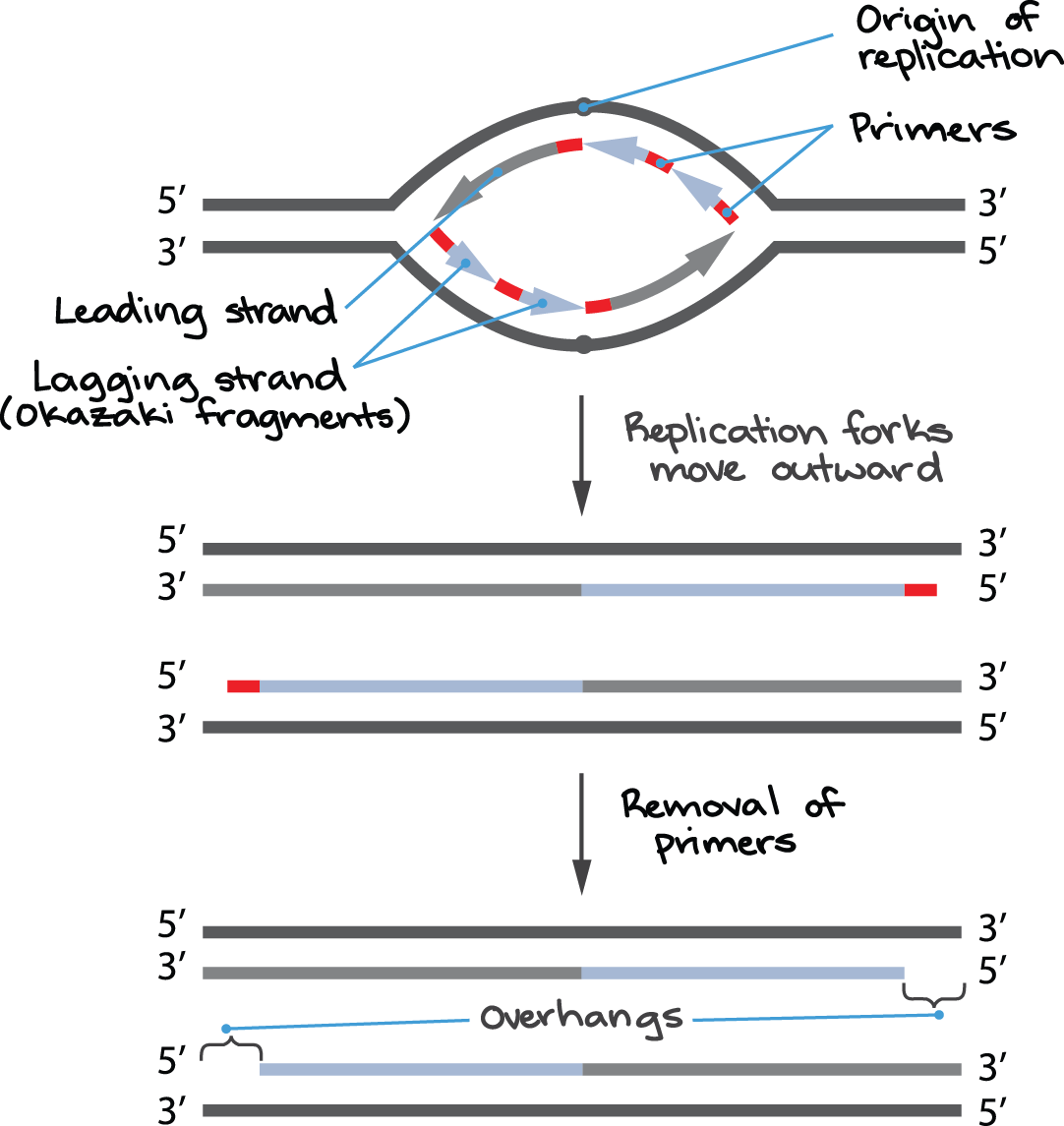

Why is this the case? When copying DNA, one of the two new DNA strands at a replication fork is made continuously, called the leading strand (Figure 3). The other strand is produced in many small pieces called Okazaki fragments, each of which begins with its own RNA primer and is known as the lagging strand.

In most cases, DNA can easily replace the primers of the Okazaki fragments, which connect to form an unbroken strand. When the replication fork reaches the end of the chromosome, however, there is (in many species, including humans) a short stretch of DNA that does not get covered by an Okazaki fragment; essentially, there is no way to start the fragment because the primer would fall beyond the chromosome end. Also, DNA cannot replace the primer of the last Okazaki fragment that does get made like other primers.

Thanks to these problems, part of the DNA at the end of a eukaryotic chromosome goes uncopied in each round of replication, leaving a single-stranded overhang. The cell recognises single-stranded DNA as damaged and degrades it. Over multiple rounds of cell division, the chromosome will get shorter and shorter as this process repeats.

In human cells, the last RNA primer of the lagging strand may be positioned as much as 70 to 100 nucleotides away from the chromosome end. Thus, the single-stranded overhangs produced by incomplete end-replication in humans are fairly long, and the chromosome shortens significantly with each round of cell division.

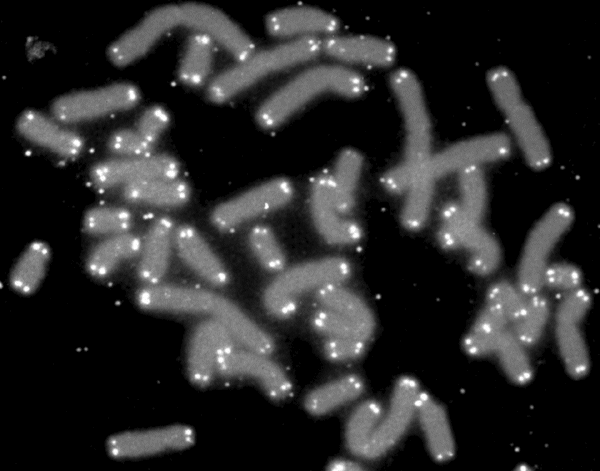

Telomeres

What would someone see if they could zoom in and look at the DNA on the tip of one of your chromosomes? They might expect to find genes or some DNA sequences involved in gene regulation. Instead, they would actually find a single sequence — TTAGGG — repeated over and over again, hundreds or even thousands of times. Repetitive regions at the very ends of chromosomes are telomeres (Figure 4). Many eukaryotic species, from human beings to unicellular protists, have telomeres. The exact telomeric sequence varies among organisms but is 5′ — TTAGGG — 3′ in humans and other mammals. Telomeres act as caps that protect the internal regions of the chromosomes, and they’re worn down a small amount in each round of DNA replication.

Telomeres need to be protected from a cell’s DNA repair systems because they have single-stranded overhangs, which “look like” damaged DNA. The overhang at the lagging strand end of the chromosome is due to incomplete end-replication (see Figure 3). The overhang at the leading strand end of the chromosome forms when enzymes cut away part of the DNA.

In some species (including humans), the single-stranded overhangs bind to complementary repeats in the nearby double-stranded DNA, causing the telomere ends to form protective loops (Figure 5). Proteins associated with the telomere ends also help protect them and prevent them from triggering DNA repair pathways.

The repeats that make up a telomere are eaten away slowly over many division cycles, providing a buffer that protects the internal chromosome regions bearing the genes (at least, for some period of time). Telomere shortening has been connected to the aging of cells, and the progressive loss of telomeres may explain why cells can only divide a certain number of times.

Telomerase

Some cells can reverse telomere shortening by expressing telomerase, an enzyme that extends the telomeres of chromosomes. Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, meaning an enzyme that can make DNA using RNA as a template.

“In the 1980s, it was discovered that some animal embryos had an enzyme called telomerase, which protects chromosomes from degrading, allowing the cells to keep actively dividing. Then, in 1989, Yale scientist Gregg Morin used HeLa cells to isolate the same enzyme in human cells for the first time. Morin hypothesized that this enzyme, found in cancer cells, was also how embryonic cells were able to rapidly divide at the beginning of life. And in 1996, he was proven right, when scientists found telomerase in human embryos — which is what allows them to grow so rapidly until birth, when human bodies stop making it.”

— 5 Important ways Henrietta Lacks Changed Medical Science by Leah Samuel, 2017.

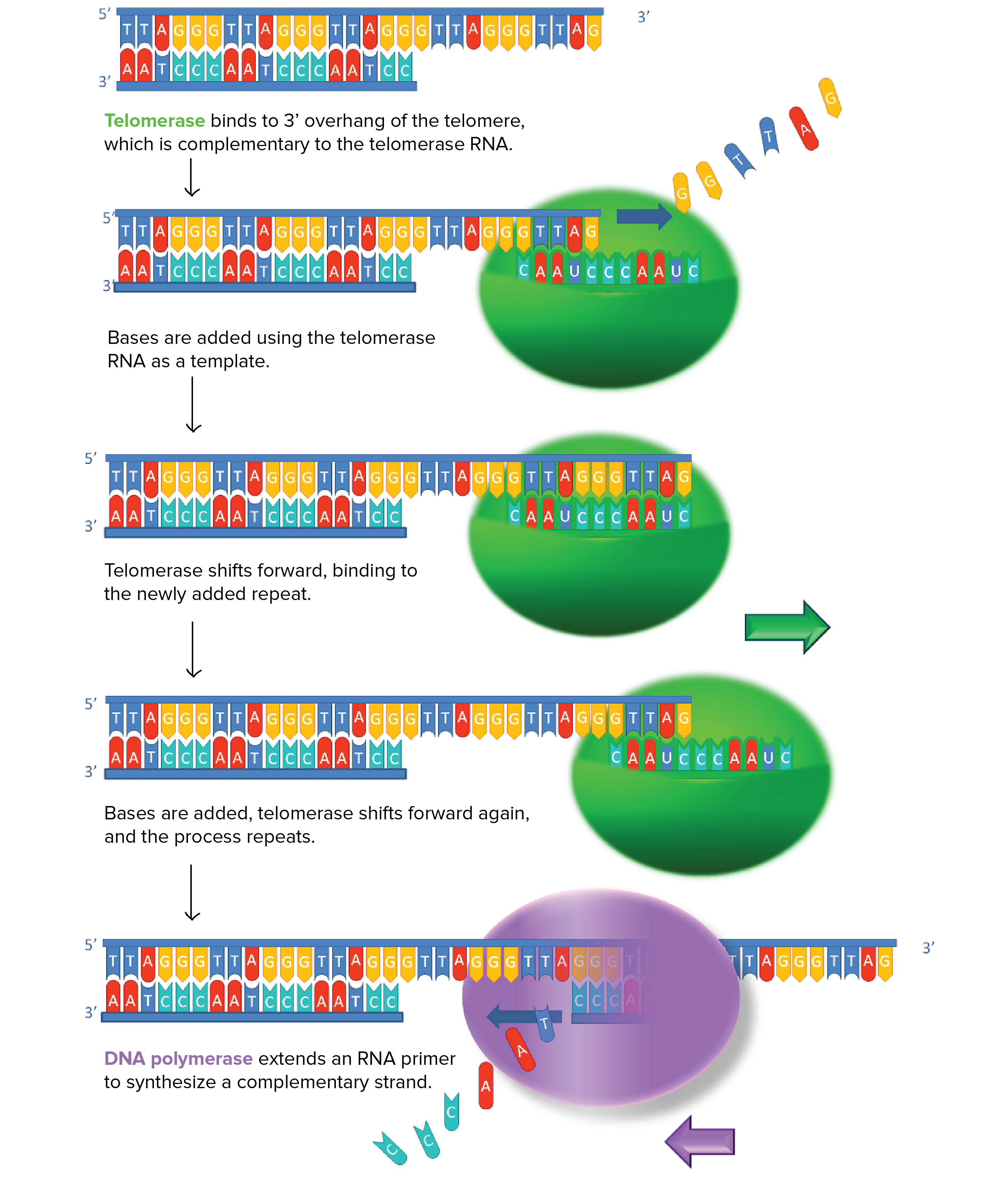

How does telomerase work? The enzyme binds to a special RNA molecule that contains a sequence complementary to the telomeric repeat (Figure 6). It extends (adds nucleotides to) the overhanging strand of the telomere DNA using this complementary RNA as a template. When the overhang is long enough, a matching strand can be made by the normal DNA replication machinery (that is, using an RNA primer and DNA polymerase), producing double-stranded DNA.

The primer may not be positioned right at the chromosome end and cannot be replaced with DNA, so an overhang is still present. However, the overall length of the telomere will be greater.

Learning Activity: Telomere Replication

- Watch the video “Telomere replication” (2:10 min) by Ryan Abbott (2017) to see how telomerase extends telomeres. Make your own notes.

Telomerase is not usually active in most somatic cells (cells of the body), but it’s active in germ cells (the cells that make sperm and eggs) and some adult stem cells. These are cell types that need to undergo many divisions, or, for germ cells, give rise to a new organism with its telomeric “clock” reset.

Interestingly, many cancer cells have shortened telomeres, and telomerase is active in these cells. If drugs could inhibit telomerase as part of cancer therapy, they could potentially stop excess division in cancer cells (and thus, the growth of the cancerous tumour).

In summary, telomeres protect coding sequences from being lost as cells continue to divide. The discovery of the enzyme telomerase clarified our understanding of how chromosome ends are maintained. For their discovery of telomerase and its action, Elizabeth Blackburn (Figure 7), Carol W. Greider, and Jack W. Szostak received the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 2009.

Telomeres and Aging

Cells that undergo cell division continue to have their telomeres shortened because most somatic cells do not make telomerase. This essentially means that telomere shortening is associated with aging. Modern medicine, preventative health care, and healthier lifestyles have increased the human life span. Because of this, there is an increasing demand for people to look younger and have a better quality of life as they age.

In 2010, scientists found that telomerase can reverse some age-related conditions in mice. This may have potential in regenerative medicine. These studies used telomerase-deficient mice with tissue atrophy, stem cell depletion, organ system failure, and impaired tissue injury responses. Telomerase reactivation in these mice caused extension of telomeres, reduced DNA damage, reversed neurodegeneration, and improved the function of the testes, spleen, and intestines. Thus, telomere reactivation can potentially treat age-related diseases in humans.

Self-Check

How do the linear chromosomes in eukaryotes ensure that its ends are replicated completely?

Show/Hide answer.

Telomerase has an inbuilt RNA template that extends the 3′-end, so the primer is synthesized and extended. Thus, the ends are protected.

Learning Activity: Telomeres

“What makes our bodies age … our skin wrinkle, our hair turn white, our immune systems weaken? Biologist Elizabeth Blackburn shares a Nobel Prize for her work in finding out the answer.” And what does this have to do with pond scum and an immortal woman?

- Watch the introductory video “The science of cells that never get old | Elizabeth Blackburn” (18:46 min) by Dr. E. Blackburn (2017), where she discusses her Nobel Prize-winning discovery of telomeres using pond scum. Take note of the particular model organism she studied and why it was so useful for her purposes. Model systems are typically chosen based on their utility in identifying new avenues of research or contributing to the mechanistic understanding of important biological problems. Make notes to answer the self-check questions below.

Self-Check

- How do the linear chromosomes in eukaryotes ensure that its ends are replicated completely?

Show/Hide answer.

Telomerase has an inbuilt RNA template that extends the 3′-end, so the primer is synthesized and extended. Thus, the ends are protected.

- What did Elizabeth mean that humans are living on a knife edge when referring to telomerase? That is, why don’t we want to guzzle telomerase?

Show/Hide answer.

Increasing telomerase helps reduce some age-related diseases. But again, it helps cancer cells to reproduce.

Key Concepts and Summary

Cell culture is an essential in vitro tool in cell biology research. This technique removes cells from an organism and grows them in optimal artificial conditions to study many different processes. Live cell culture enables the development of model systems for understanding physiological processes in the human body, mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, drug screening and development, and much more. This section provided an overview of the categories of cells (Primary vs. Continuous/Established Cell Lines), how to establish suitable growth conditions for cells, and the principles of cell culture lab practices. Cells are difficult to culture outside the body unless specific components are present in the culture medium and proper incubation conditions are used.

This section also introduced the end-replication problem and its connection to continuous/established cultured cell lines. As most cells divide, their telomeres shorten until they reach a critical limit when they can no longer divide. This limit is known as the Hayflick limit, and it is a major limitation of primary cells. Some cells can get around the Hayflick limit. The ends of the chromosomes pose a problem as DNA cannot replace the primer RNA at the 5’ ends of the DNA, and the chromosome becomes progressively shorter. The Nobel Prize-winning discovery of telomerase in Tetrahymena cells revealed how an enzyme with an inbuilt RNA template can protect the ends of chromosomes containing repetitive DNA sequences known as telomeres. Telomerase is especially active in cells undergoing repetitive cell division cycles, such as embryonic and cancer cells.

Assessments

All assignments, quizzes, and information about how to complete quizzes and submit assignments for this course are located in your Moodle Course Shell.

Quiz

Complete Unit 1 Quiz found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Assignment

Complete Unit 1 Assignment found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Long Descriptions

Figure 2 Image Description: (a) Individual cells from lung tissue are isolated into a primary cell culture. Then, the cells multiply until they fill the petri dish, resulting in contact inhibition. After that, some cells are transferred to a new medium, known as a secondary cell culture. (b) Transformed cells or individual cells from a tumour in lung tissue are isolated in a continuous cell line culture. Then, the cells multiplying overflows the petri dish because they are unaffected by contact inhibition. [Return to Figure 2]

Figure 3 Image Description: In the origin of replication, the top of the replication bubble has a leading strand facing left, followed by two primers. The bottom has a leading strand facing right, followed by two logging strands (known as Okazaki fragments). The next step results in replication forks moving outward into four strands; the two replication strands each have a red primer cap on opposing sides. The final step removes these primers, resulting in an overhang on both strands. [Return to Figure 3]

Figure 6 Image Description: Telomerase extends DNA telomeric sequences in the following steps:

- Telomerase binds to the 3′ overhang of the telomere, which is complementary to the telomerase RNA.

- Bases are added using the telomerase RNA as a template.

- Telomerase shifts forward, binding to the newly added repeat.

- Bases are added, telomerase shifts forward again, and the process repeats.

- DNA polymerase extends an RNA primer to synthesize a complementary strand. [Return to Figure 6]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: HeLa-I [modified] by National Institutes of Health (2007), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 2: Figure 6.19 [modification of “Micrographs” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] from OpenStax Microbiology (Parket et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Image 2 [modification of Telomere shortening by Zlir’a (2012) under a CC0 1.0 license] from Telomeres and telomerase by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC0 1.0 license.

- Figure 4: Telomere caps by U.S. Department of Energy Human Genome Program (2008), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 5: Telomere by Y tambe and Samulili (2004), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 6: Image 4 [modification of Working principle of telomerase by Fatma Uzbas under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license] from Telomeres and telomerase by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 14.16 by US Embassy Sweden, from OpenStax Biology2e (Clark et al. 2018), is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

Applied Biological Materials – abm. 1) Cell culture tutorial – an introduction [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Nov 13, 7:43 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpDke-Sadzo.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Figures 4.8, 23.2, 23.3. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Telomeres and telomerase. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Image 2. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/dna-as-the-genetic-material/dna-replication/a/telomeres-telomerase.

National Institutes of Health. 2007. HeLa-I [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2013 Nov 10; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HeLa-I.jpg.

Parker N, Schneegurt M, Tu A-HT, Lister P, Forster BM. 2016. Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction.

Parker N, Schneegurt M, Tu A-HT, Lister P, Forster BM. 2016. Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Figure 6.19. https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/6-3-isolation-culture-and-identification-of-viruses.

Ryan Abbott. Telomere replication [Video]. YouTube. 2017 May 16, 2:10 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NS0jBPurWQ.

Samuel L, STAT. 2017. 5 ways Henrietta Lacks changed medical science [Blog]. New York (NY): Scientific American; [accessed 2022 Jun 9]. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/5-ways-henrietta-lacks-changed-medical-science/.

TED. The science of cells that never get old | Elizabeth Blackburn [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Dec 15, 18:46 minutes. [accessed 2014 Jan 18]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2wseM6wWd74.

TED-Ed. The immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks – Robin Bulleri [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Feb 8, 4:26 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22lGbAVWhro.

U.S. Department of Energy Human Genome Program. 2008. Telomere caps [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated2008 Nov 19; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Telomere_caps.gif.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Subculture (biology). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2022 Jan 6; accessed 2023 Dec 11]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Subculture_%28biology%29&oldid=1064146714.

Y tambe, Samulili. 2004. Telomere [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2005 Mar 12; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Telomere.png.