2.2 Movement of Substances across Membranes — Passive Transport

Introduction

Have you been through airport security lately? If so, you have probably noticed that it is carefully designed to let some things in (e.g., passengers with tickets) and keep others out (e.g., weapons, explosives, and bottled water). Flight attendants, captains, and airport personnel travel through quickly via a special channel, while regular passengers pass through more slowly, sometimes with a long wait in line.

In many ways, airport security is a lot like the plasma membrane of a cell. Cell membranes are selectively permeable, regulating which substances can pass through and how much of each substance can enter or exit at a given time. Selective permeability is essential to a cell’s ability to obtain nutrients, eliminate wastes, and maintain a stable interior environment different from its surroundings (maintain homeostasis).

Some cells require larger amounts of specific substances and must have a way of obtaining these materials from extracellular fluids. This process may happen passively, as certain materials move back and forth, or the cell may have special mechanisms to facilitate transport. Some materials are so important to a cell that it spends some of its energy (hydrolyzing adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) to obtain these materials. Interestingly, most cells spend a lot of their energy (approximately one-third) on maintaining an imbalance of sodium and potassium ions between the cell’s interior and exterior.

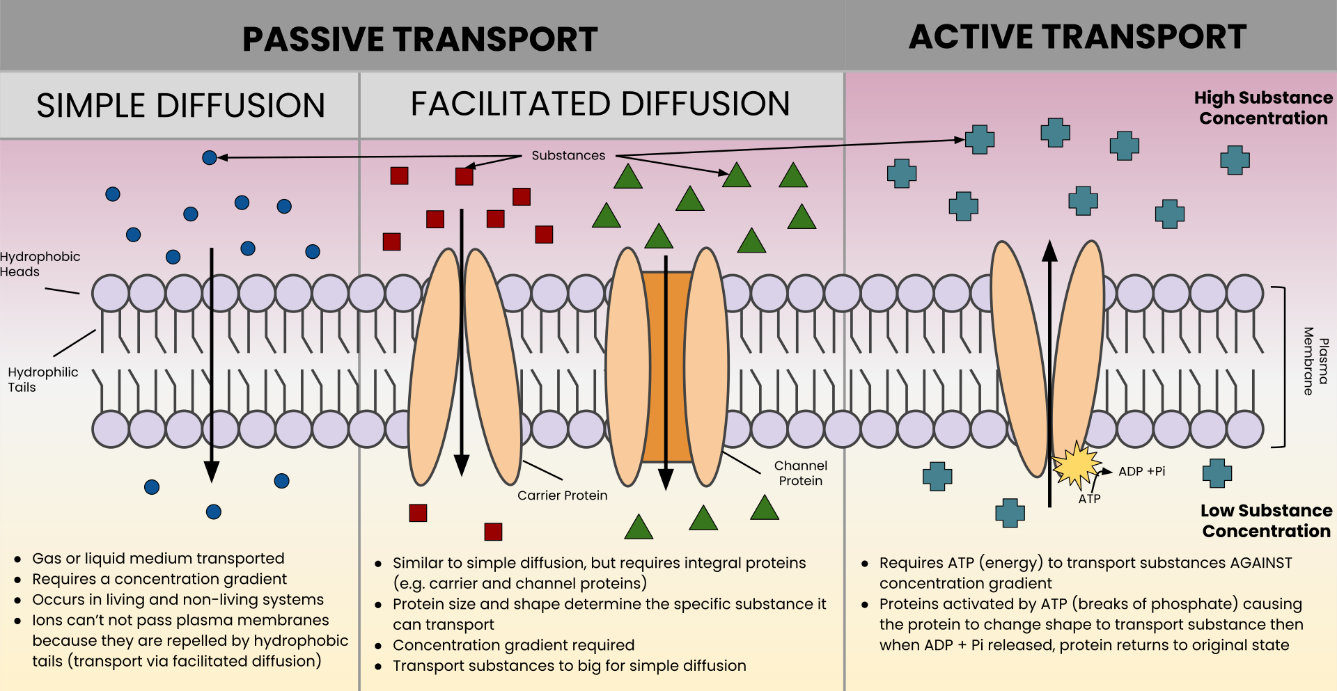

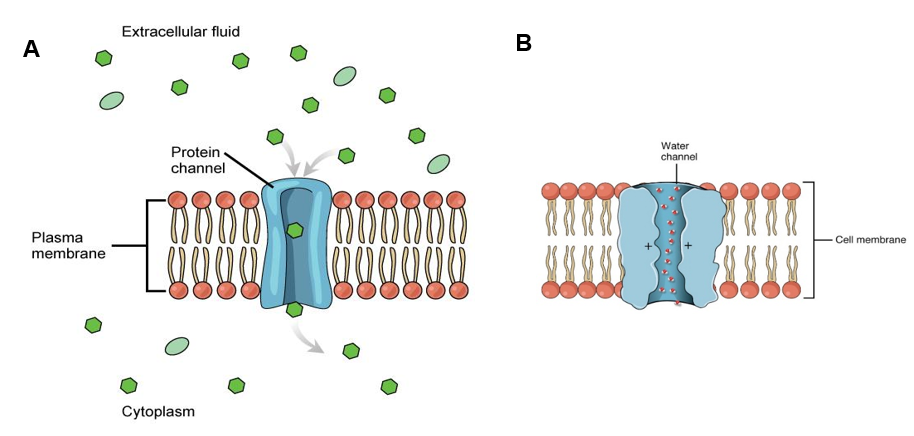

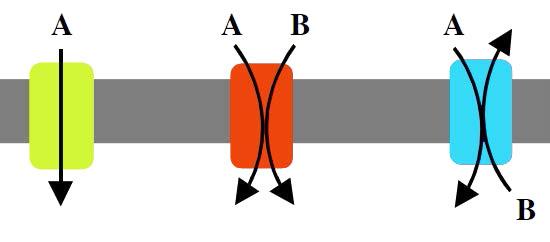

The most direct forms of membrane transport are passive. Passive transport is a naturally occurring phenomenon that does not require the cell to exert any energy to move substances from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. A concentration gradient is a region of space over which the concentration of a substance changes; substances will naturally move down their gradients, from an area of higher to an area of lower concentration. In cells, some molecules can move down their concentration gradients by crossing the lipid portion of the membrane directly. Meanwhile, others must pass through membrane proteins in a process called facilitated diffusion (Figure 1). Unit 2, Topic 2 goes into more detail about membrane permeability and different modes of passive transport. In Unit 2, Topics 3 and 4, we will discuss active transport and how it relates to passive transport.

Unit 2, Topic 2 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 2, Topic 2, you will be able to:

- Describe diffusion and the factors that affect how materials move across the cell membrane.

- Explain why and how passive transport occurs.

- Describe the process of osmosis and explain how concentration gradient affects osmosis.

- Define tonicity and describe its relevance to osmosis in humans and plants.

- Describe the need for facilitated diffusion.

- Describe the mechanisms of facilitated diffusion and the proteins involved.

- Integrate your knowledge from Unit 2, Topic 1 by drawing your own fluid mosaic bilayer and hydropathy plots of membrane transport proteins.

| Unit 2, Topic 2—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 2, Topic 2 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Selective Permeability. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Diffusion. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Tonicity. | 5 |

| ✮ Complete Learning Activity: Aquaporins. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane Channels. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Channel Proteins. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Composition and Transport. | 15 |

Selective Permeability

Recall that plasma membranes are amphiphilic, containing hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions (see Unit 2, Topic 1). This characteristic helps move some materials through the membrane while hindering the movement of others. Nonpolar and lipid-soluble material with a low molecular weight can easily slip through the hydrophobic lipid core of the membrane. Substances such as the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K readily pass through the plasma membranes in the digestive tract and other tissues. Fat-soluble drugs and hormones also gain easy entry into cells and readily transport themselves into the tissues and organs of the body. Oxygen and carbon dioxide molecules have no charge and pass through membranes by simple diffusion.

Polar substances can present problems for the membrane. While some polar molecules connect easily with the cell’s outside, they cannot readily pass through the plasma membrane’s hydrophobic lipid core. Water molecules, for instance, cannot cross the membrane rapidly; however, thanks to their small size and lack of a full charge, they can cross at a slow rate. Furthermore, while small ions could easily slip through the spaces in the membrane’s mosaic, their charge prevents them from doing so. Ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride must have special means of moving through plasma membranes. Larger charged and polar molecules, like sugars and amino acids, also need the help of various transmembrane proteins to facilitate transport across plasma membranes.

Learning Activity: Selective Permeability

Biological membranes are selectively permeable; some molecules can cross while others cannot. One way to affect this is through pore size.

- Go to LabXchange and complete the “Diffusion Across a Semipermeable Membrane” simulation by The Concord Consortium (2020). Change the pore size with the slider to change the permeability of the membrane to the different types of molecules. Trace an individual molecule to see the path it takes.

Passive Transport: Diffusion, Osmosis, and Facilitated Diffusion

Diffusion

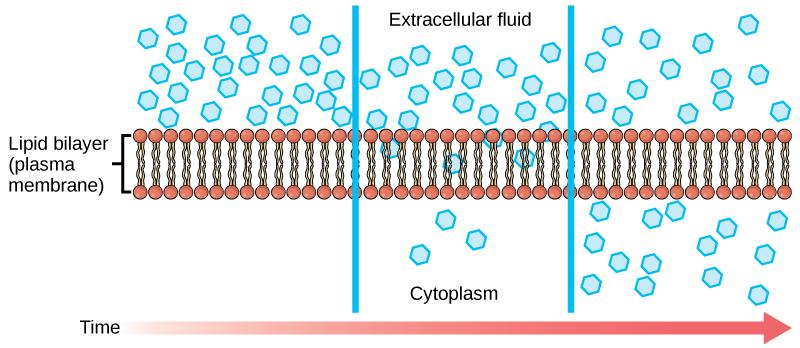

Diffusion is a passive process of transport where a single substance moves from an area of high concentration to one of low concentration until the concentration is equal across the space. You are familiar with the diffusion of substances through the air. For example, think about someone opening a bottle of perfume in a room filled with people. The perfume smell is at its highest concentration in the bottle and its lowest concentration at the edges of the room. The perfume vapour will diffuse or spread away from the bottle, and gradually, more people will smell it as it spreads. Certain materials use diffusion move within the cell’s cytosol and the plasma membrane (Figure 2). Diffusion expends no energy.

The left part of Figure 2 shows a substance on one side of a membrane only in the extracellular fluid. The middle part shows that, after some time, some of the substance has diffused across the plasma membrane, from the extracellular fluid, and into the cytoplasm. The right part shows that, after more time, an equal amount of the substance is on each side of the membrane.

Each separate substance in a medium, such as the extracellular fluid, has a unique concentration gradient independent of other materials’ concentration gradients. Each substance will passively diffuse according to that gradient. Thus, over time, the net movement of molecules will move out of the more concentrated area and into the less concentrated one until the concentrations become equal. At this point, it is equally likely for a molecule to move in either direction.

A concentration gradient itself is a form of stored (potential) energy; this energy is used up as the concentrations equalize. Within a system, various substances will have different diffusion rates in the medium. If other factors are equal, a stronger concentration gradient (larger concentration difference between regions) results in faster diffusion. Thus, different molecules in a single cell can have different diffusion rates and directions. For example, oxygen might move into the cell by diffusion, while, at the same time, carbon dioxide might move out according to its own concentration gradient.

Factors That Affect Diffusion

Molecules move constantly in a random manner at a rate dependent on their mass, environment, and thermal energy (a function of temperature). This movement accounts for the diffusion of molecules through whatever medium they are localized. A substance will tend to move into any space available until it evenly distributes throughout the space. After a substance diffuses completely through a space, removing its concentration gradient, molecules will still move around. However, there will be no net movement of the number of molecules from one area to another. This lack of a concentration gradient in which there is no net movement of a substance is known as dynamic equilibrium. While diffusion occurs in the presence of a concentration gradient, several factors affect the diffusion rate.

Extent of the Concentration Gradient

The greater the difference in concentration, the more rapid the diffusion. The closer the distribution of the material gets to equilibrium, the slower the diffusion rate becomes.

Mass of the Molecules Diffusing

Heavier molecules move more slowly; therefore, they diffuse slower. The reverse is true for lighter molecules.

Temperature

Higher temperatures increase the energy and, therefore, the movement of the molecules, increasing the diffusion rate. Lower temperatures decrease the energy of the molecules, thus decreasing the diffusion rate.

Solvent Density

As the density of a solvent increases, the diffusion rate decreases. The molecules slow down because they have more difficulty getting through the denser medium. As a medium becomes less dense, diffusion increases. Since cells primarily use diffusion to move materials within the cytoplasm, any increase in the cytoplasm’s density will inhibit the movement of the materials. An example is a person experiencing dehydration. As the body’s cells lose water, the diffusion rate decreases in the cytoplasm, and the cells’ functions deteriorate. Neurons tend to be very sensitive to this effect. Dehydration frequently leads to unconsciousness and possibly coma because of the decreased diffusion rate within the cells.

Solubility

As discussed earlier, nonpolar or lipid-soluble materials pass through plasma membranes more easily than polar materials, allowing for a faster diffusion rate.

Plasma Membrane Surface Area and Thickness

Increased surface area increases the diffusion rate, whereas a thicker membrane reduces it.

Distance Travelled

The greater the distance that a substance must travel, the slower the diffusion rate. This places an upper limitation on cell size. A large, spherical cell will die because nutrients or waste cannot reach or leave the centre of the cell. Therefore, cells must either be small in size, as in the case of many prokaryotes, or flattened, as with many single-celled eukaryotes.

Self-Check

Discuss why the following affect the rate of diffusion: molecular size, temperature, solution density, and the required distance to travel.

Click to reveal answer

Heavy or large molecules move more slowly than lighter ones. It takes more energy in the medium to move them along.

Increasing or decreasing temperature increases or decreases the energy in the medium, affecting molecular movement.

The denser a solution is, the harder it is for molecules to move through it, causing diffusion to slow down due to friction.

Living cells require a steady supply of nutrients and a steady rate of waste removal. If the distance these substances need to travel is too great, diffusion cannot move nutrients and waste materials efficiently to sustain life.

Learning Activity: Diffusion

The passage of water in and out of cells is crucial to their function. Although water can directly pass through these membranes, it moves more quickly through channels made by proteins that bridge the inside and outside of a cell.

Use this interactive exercise to explore the structure of an aquaporin channel, which allows only water to pass into and out of a cell.

- Go to the following sites, make your own notes and keep a copy:

- “Aquaporins Claymation Project” (1:52 min) by Ssaucita (2011).

- “Aquaporins” simulation by The Concord Consortium (2020).

- “Aquaporins” (8:07 min) by Andrey K (2015).

- “Aquaporins Claymation Project” (1:52 min) by Ssaucita (2011).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the relationship between red blood cells, frog eggs and aquaporin channels?

- What are aquaporins?

- How many protein subunits make up an aquapore? What is their secondary structure? How many pores are there for water to fit through an aquapore?

- How do these pores attract water? Are they selective?

- How is electrical charge used to orient the water molecules as they pass through the water channel?

Osmosis

Osmosis is the movement of water through a semipermeable membrane according to the water’s concentration gradient across the membrane, which is inversely proportional to the solutes' concentration. While the term diffusion refers to the transport of material (other than water) across membranes and within cells, the term osmosis refers specifically to the transport of water across a membrane. Not surprisingly, the aquaporins that facilitate water movement play a large role in osmosis, most prominently in red blood cells and kidney tubule membranes.

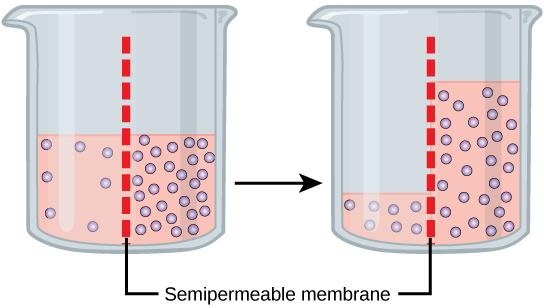

Osmosis is a special case of diffusion. Like other substances, water moves from an area of high concentration to a low concentration. Imagine a beaker with a semipermeable membrane separating the two sides or halves. Both sides of the membrane have the same water level, but there are different concentrations of solutes on each side of the membrane, and the different solutes cannot cross the membrane.

In Figure 3, there is a container with its contents separated by a semipermeable membrane. Initially, there is a high solute concentration on the right side of the membrane and a low concentration on the left. Over time, water diffuses across the membrane toward the side of the container that initially had a higher concentration of solute (lower concentration of water not bound to solute). As a result of osmosis, the water level is higher on this side of the membrane, and the solute concentration is the same on both sides.

The beaker has a solute mixture on either side of the membrane. A principle of diffusion is that the molecules move around and will spread evenly throughout the medium if they can. However, only the material capable of getting through the membrane will diffuse through it. In this example, the solute cannot diffuse through the membrane, but the water can. Water has a concentration gradient in this system. Thus, water will diffuse down its concentration gradient, crossing the membrane to the side where it is less concentrated. This diffusion of water through the membrane — osmosis — will continue until the water’s concentration gradient reaches zero or until the water’s hydrostatic pressure balances the osmotic pressure. Hydrostatic pressure is the pressure at a point in a column of fluid. Osmosis constantly occurs in living systems.

Self-Check

Why does water move through a membrane?

Show/Hide answer.

Water moves through a membrane in osmosis because there is a concentration gradient across the membrane of solute and solvent. The solute cannot effectively move to balance the concentration on both sides of the membrane, so water moves to achieve this balance.

Tonicity

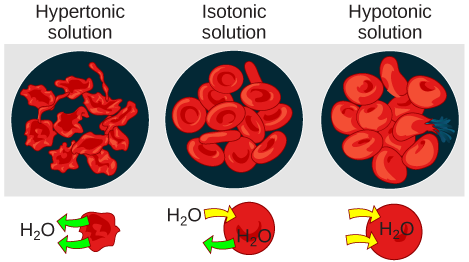

Tonicity describes the amount of solute in a solution. The measure of the tonicity of a solution, or the total amount of solutes dissolved in a specific amount of solution, is called its osmolarity. Three terms — hypotonic, isotonic, and hypertonic — are used to relate the osmolarity of a cell to the osmolarity of the extracellular fluid that contains the cells.

In a hypotonic solution, such as tap water, the extracellular fluid has a lower concentration of solutes than the fluid inside the cell, so water enters the cell. In living systems, the point of reference is always the cytoplasm, so the prefix hypo- means that the extracellular fluid has a lower solute concentration (or a lower osmolarity) than the cell cytoplasm. It also means that the extracellular fluid has a higher water concentration than the cell. In this situation, water follows its concentration gradient and enters the cell. This movement may cause an animal cell to burst or lyse.

In a hypertonic solution — where the prefix hyper- refers to the extracellular fluid having a higher solute concentration than the cell’s cytoplasm — the fluid contains less water than the cell (e.g., seawater). Since the cell has a lower solute concentration, the water leaves the cell. In other words, the solute draws the water out of the cell. This movement may cause an animal cell to shrivel or crenate.

In an isotonic solution, the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the cell. If the solute concentration of the cell matches the extracellular fluid, no net movement of water into or out of the cell occurs. Blood cells take on characteristic appearances in hypertonic, isotonic, and hypotonic solutions (Figure 4).

Self-Check

A doctor injects a patient with what the doctor thinks is isotonic saline solution. The patient dies, and an autopsy reveals that many red blood cells have burst.

Do you think the solution the doctor injected was really isotonic?

Show/Hide answer.

No, it must have been hypotonic, as a hypotonic solution would cause water to enter the cells, thereby making them burst.

Some organisms, such as plants, fungi, bacteria, and some protists, have cell walls that surround the plasma membrane and prevent cell lysis. The plasma membrane can only expand to the limit of the cell wall, so the cell will not lyse. In fact, the cytoplasm in plants is always slightly hypertonic compared to the cellular environment, and water will always enter a cell if water is available. This influx of water produces turgor pressure, stiffening the cell walls of the plant (Figure 5). In non-woody plants, turgor pressure supports the plant. If plant cells become hypertonic (occurs in drought or if a plant is not watered adequately), water leaves them. Plants lose turgor pressure in this condition and wilt.

Facilitated Transport

In facilitated transport (also called facilitated diffusion), materials that cannot use simple diffusion are transported passively across the plasma membrane with the help of membrane proteins. A concentration gradient exists that would allow these materials to diffuse into the cell without expending cellular energy. However, these materials are polar molecules or ions that the cell membrane’s hydrophobic parts repel. Facilitated transport proteins shield these materials from the membrane’s repulsive force, allowing them to diffuse into the cell.

The transported material first attaches to protein or glycoprotein receptors on the plasma membrane’s exterior surface. The substances then pass through specific integral proteins to move into the cell. Some of these integral proteins form a pore or channel through the phospholipid bilayer; others are carrier proteins that contain a binding site for a specific substance to aid its diffusion through the membrane.

Channels

The integral proteins involved in facilitated transport are types of transport proteins that function as either channels or carriers/transporters for the material. Channels are specific to the transported substance. They have hydrophilic domains exposed to the intracellular and extracellular fluids with hydrophilic channels (or pathways) through their core, providing a hydrated opening through the membrane layers (Figure 6A). As such, channels are often described as “pores” in the membrane. Passage through the channel allows polar compounds to avoid the nonpolar central layer of the plasma membrane that would otherwise slow or prevent their entry into the cell. Three types of transmembrane protein channels are ion channels, porins, and aquaporins.

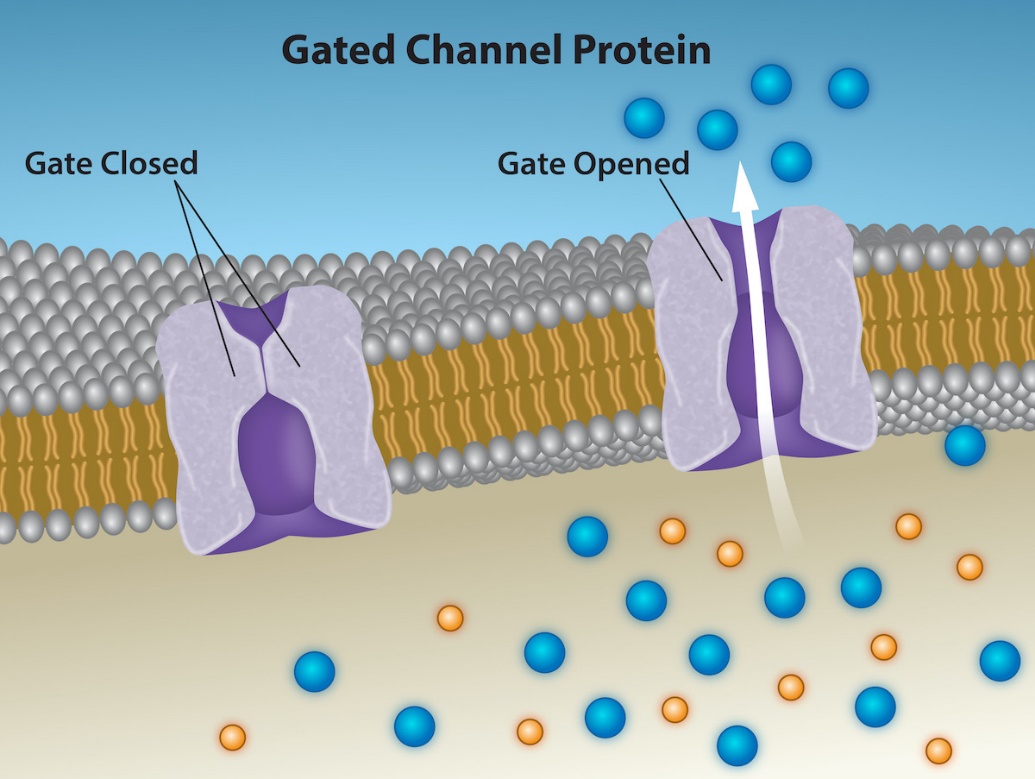

Channel proteins consist of two forms: one form is open at all times, allowing substances to move with the gradient (referred to as leakage channels), and the second form is “gated,” which controls the channel opening and closing. No matter the form, channel proteins will facilitate the passive diffusion of substances with the concentration gradient. Aquaporins are channel proteins opened at all times to allow water to pass through the membrane at a very high rate (Figure 6B). Alternatively, an example of a gated channel is when a particular ion attaches to the channel protein and controls the opening, or other mechanisms or substances may be involved (Figure 7).

In some tissues, sodium and chloride ions pass freely through open channels, whereas, in other tissues, a gate must open to allow passage. An example of this occurs in the kidney, which uses both channel forms in different parts of the renal tubules. Cells that transmit electrical impulses, such as nerve and muscle cells, have gated channels for sodium, potassium, and calcium in their membranes. Opening and closing these channels changes the relative concentrations of these ions on opposing sides of the membrane, which facilitates electrical transmissions along membranes (nerve cells) or in muscle contractions (muscle cells).

Unit 2, Topic 4 explores these three types of gated channels in more detail:

- Voltage-gated

- Ligand-gated

- Mechanically gated

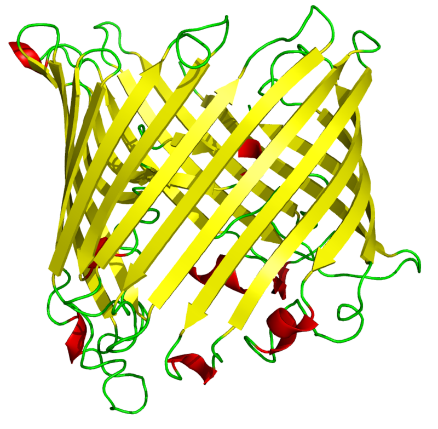

Figure 8: An 18-strand β barrel. Bacterial sucrose-specific porin from S. typhimurium sits in a membrane and allows sucrose to diffuse through. (PDB: 1A0S). (Regalis 2007/Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 3.0

Porins are called beta barrel proteins that cross a cellular membrane and act as a pore through which molecules can diffuse (Figure 8). In protein structures, a beta barrel is a beta-pleated sheet composed of tandem repeats (several adjacent copies) that twist and coil to form a closed toroidal structure in which the first strand bonds to the last one (hydrogen bond). They are present in the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria, some gram-positive mycobacteria (mycolic acid-containing actinomycetes), mitochondria, and chloroplast.

Is it a coincidence that porins are present in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts?

Learning Activity: Tonicity

Some organisms (e.g., plants, fungi, bacteria, and some protists) have cell walls surrounding the plasma membrane to prevent cell lysis.

- Label the tonicity of the solution represented in each of the three diagrams of a plant cell below.

Figure 5: The turgor pressure within a plant cell depends on the tonicity of the solution it is in. (Fowler et al. 2013/Concepts of Biology/OpenStax) CC BY 4.0

Show/Hide answer.

The left part of this image shows a plant cell bathed in a hypertonic solution; the plasma membrane has pulled away completely from the cell wall, and the central vacuole has shrunk. The middle part shows a plant cell bathed in an isotonic solution, where the plasma membrane has pulled away from the cell wall a bit, and the central vacuole has shrunk. The right part shows a plant cell in a hypotonic solution; the central vacuole is large, and the plasma membrane presses against the cell wall.

✮Learning Activity: Aquaporins

Biochemical analysis of the Rhesus blood group antigen led to the serendipitous discovery of AQP1, the first molecular water channel. Found throughout nature, aquaporin water channels allow for high water permeability in cell membranes. AQP1 has been characterized biophysically, and the atomic structure of AQP1 is known. Identifying the Colton blood group antigen on the extracellular domain of AQP1 could identify rare individuals who are AQP1-null and manifest a subclinical form of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Thirteen homologous proteins exist in humans. Some transport only water (aquaporins); others transport water plus glycerol (aquaglyceroporins). The body requires these proteins to generate physiological fluids (urine, cerebrospinal fluid, aqueous humor, sweat, saliva, and tears). The involvement of aquaporins in multiple clinical states is becoming recognised — renal concentration, fluid retention, blindness, skin hydration, brain edema, thermal stress, glucose homeostasis, malaria, and even arsenic poisoning.

Aquaporins are particularly important in plant biology. This information now provides the challenge of developing new technologies to manipulate aquaporins for clinical or agricultural benefits.

- Go to LabXchange and watch the video “Aquaporin Water Channels – From Transfusion Medicine to Malaria” (57:36 min) by NIH Center for Information Technology (2021). Make notes using the following guide:

- Write down all terminology relevant to the content you are learning in Unit 2, Topic 2.

- Write down and look up all unfamiliar terminology used by Peter Agre in his talk.

- Note the tissues in which aquaporins are important and why.

- Relate the labelling process used to visualize aquaporins in the proximal nephron to the content you learned in Topic 1, Unit 2.

- Note what process makes water move from the apical to the basal regions of the cells in the proximal nephron.

- Answer the question: How are aquaporins related to red blood cell antigens?

- What did you love learning about from Peter Agre’s talk?

Learning Activity: Membrane Channels

In this activity, you will insert channels into a simulated membrane and see what happens. See how different types of channels allow particles to move through the membrane.

- Go to the LabXchange website and complete the “Membrane Channels” simulation activity by PhET (2020).

- Make your own starting concentration gradients with two different molecules across a membrane by clicking on the red knobs on the left. Create your own semi-permeable membrane by dragging the options from the bottom onto the membrane. Predict what will happen to your concentration gradients before you open your chosen channels (on the top right).

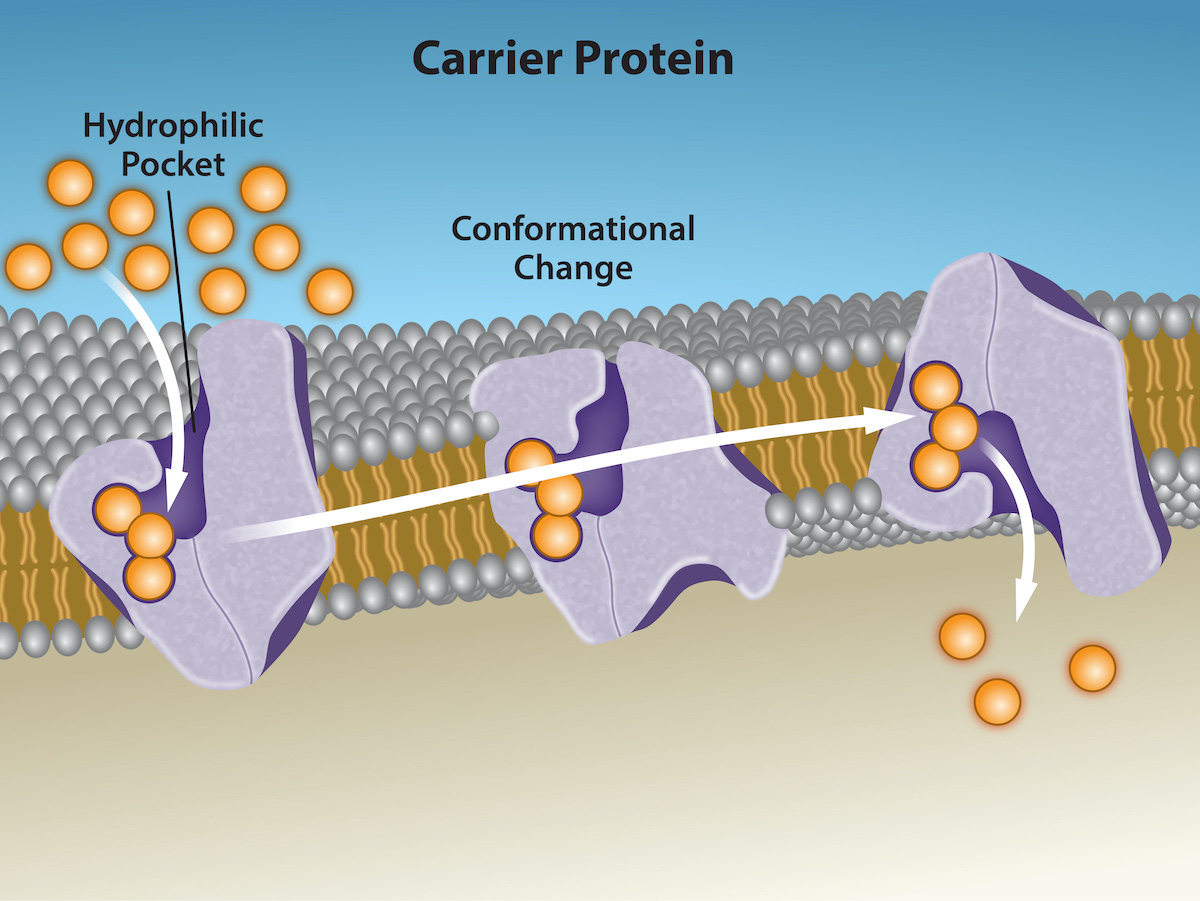

Carrier/Transporter Proteins

Another type of protein embedded in the plasma membrane is a carrier/transporter protein. This aptly named protein binds a substance and triggers a change of its shape, moving the bound molecule from one side of the membrane to another and can result in movement that can be with (passive) or against (active) the concentration gradient. Carrier proteins are typically specific for a single substance, which adds to the plasma membrane’s overall selectivity.

Figure 9 shows a carrier/transporter protein embedded in the membrane with an opening that initially faces the extracellular surface. After a substance binds the carrier, it changes shape so that the opening faces the cytoplasm, and the substance is released.

An example of this process occurs in the kidney. In one part, the kidney filters glucose, water, salts, ions, and amino acids that the body requires. Another part of the kidney then reabsorbs this filtrate, which includes glucose. Since there are only a finite number of carrier proteins for glucose, these proteins do not transport excess glucose they cannot handle, and the body excretes it through urine. In a diabetic individual, the term is “spilling glucose into the urine.” A different group of carrier proteins, glucose transport proteins (GLUTs), is involved in transporting glucose and other hexose sugars through plasma membranes within the body.

The transport rate by channel and carrier proteins differs by how they physically interact with their substrates. Channel proteins facilitate diffusion at a rate of tens of millions of molecules per second; meanwhile, carrier proteins work at a rate of a thousand to a million molecules per second.

Learning Activity: Channel Proteins

- Watch the video “Facilitated Diffusion” (6:34 min) by Khan Academy (2015) to understand how channel proteins and carrier proteins facilitate diffusion across a cell membrane (passive transport). Make notes and keep a copy for study purposes.

- You should be able to recognise the difference between integral membrane proteins that facilitate passive transport. In the following image, drag and drop the names to identify the integral membrane protein types labelled 1 and 2.

Figure 10: Scheme facilitated diffusion in cell membrane (Villarreal 2007/Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain

Direction of Transport: Uniports, Antiports, and Symports

A protein involved in moving only one type of molecule across a membrane is called a uniport. Meanwhile, a protein that moves two different types of molecules in the same direction across the membrane is called a symport. If two different types of molecules move in opposite directions across the bilayer, the protein is called an antiport (Figure 11).

Learning Activity: Composition and Transport

This activity provides an overview of plasma membrane composition and transport.

- Watch this video “Cell membrane 3D Animation” (4:33 min) by H Productions (2020) and complete the following:

- Draw and label your own plasma membrane, including ALL relevant macromolecular components.

- List the three main functions of plasma membranes.

- Include three separate regions showing simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion through a channel and facilitated diffusion through a carrier/transporter.

- Describe how you would test the mobility of your membrane components (integrate with Unit 2, Topic 1).

- Draw a hydropathy plot of a 420 amino acid transmembrane protein that has one transmembrane region beginning at residue 150 and a second at 300. Use the template below. The template can be downloaded as a PDF for drawing electronically or for printing out and drawing by hand. Integrate with Unit 2, Topic 1.

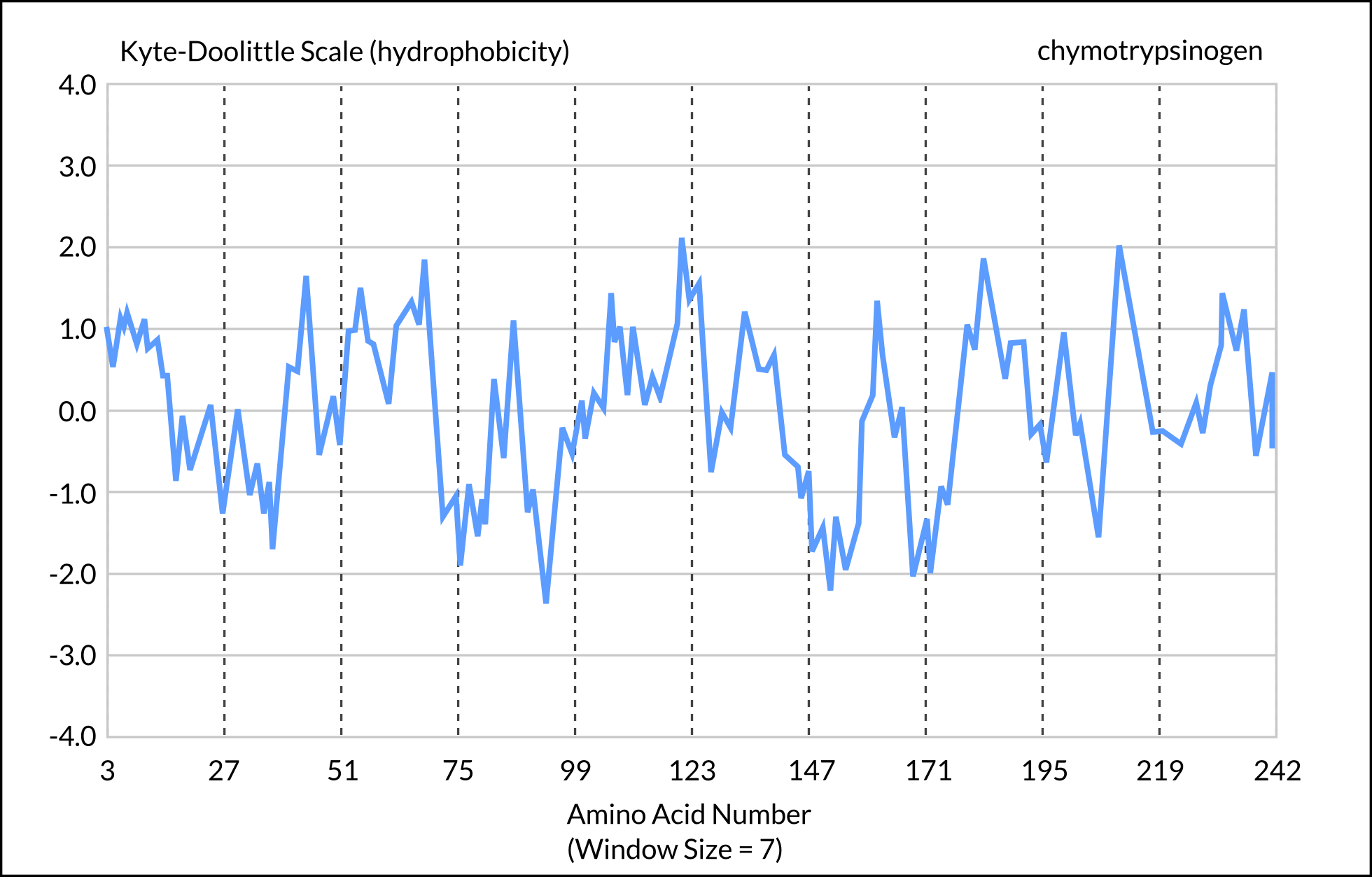

- Here is a hydropathy plot for a water-soluble protein (Figure 12). Values above 0 indicate hydrophobicity of amino acid R groups. Values below zero indicate hydrophilicity of amino acid R groups. How would you compare this plot to the one in the previous question? In other words, how would you determine that this isn’t an integral membrane protein with multiple transmembrane domains? Where would the hydrophobic amino acids in this protein be found relative to its tertiary conformation?

Figure 12: Hydropathy plot for a water-soluble protein. (Jakubowski 2019/Biochemistry Online/LibreTexts) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [Long Description]

Key Concepts and Summary

The passive forms of transport, diffusion and osmosis move material of small molecular weight. Substances diffuse from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration, and this process continues until the substance becomes evenly distributed in a system. In solutions with more than one substance, each type of molecule diffuses according to its own concentration gradient. Many factors can affect the diffusion rate, including concentration gradient, the sizes of the particles that are diffusing, and the temperature of the system.

In living systems, selectively permeable plasma membranes mediate the diffusion of substances into and out of cells. Some materials diffuse readily through the membrane, but others cannot, and their passage is only made possible by protein channels and carriers. The chemistry of living things occurs in aqueous solutions, and balancing the concentrations of those solutions is an ongoing problem. In living systems, diffusion of some substances would be slow or difficult without membrane proteins.

- Substances diffuse according to their concentration gradient; within a system, different substances in the medium will each diffuse at different rates according to their individual gradients.

- After a substance has diffused completely through a space (removing its concentration gradient), molecules still move around; however, there will be no net movement of the number of molecules from one area to another. This state is known as dynamic equilibrium.

- Several factors affect the diffusion rate of a solute, including the mass of the solute, the temperature of the environment, solvent density, and distance travelled.

- Osmosis occurs according to the concentration gradient of water across the membrane, which is inversely proportional to the concentration of solutes.

- Osmosis occurs until the concentration gradient of water reaches zero or until the hydrostatic pressure of the water balances the osmotic pressure.

- Osmosis occurs when there is a concentration gradient of a solute within a solution, but the membrane does not allow diffusion of the solute.

- A concentration gradient exists that allows ions and polar molecules to diffuse into the cell, but the hydrophobic parts of the cell membrane repel these materials.

- Facilitated diffusion uses integral membrane proteins to move polar or charged substances across the hydrophobic regions of the membrane.

- Channel proteins can aid in the facilitated diffusion of substances by forming a hydrophilic passage through the plasma membrane through which polar and charged substances can pass.

- Channel proteins can be open at all times, constantly allowing a particular substance into or out of the cell, depending on the concentration gradient; they can also be gated, and only a particular biological signal can open them.

- Carrier proteins aid in facilitated diffusion by binding a particular substance and altering its shape to bring that substance into or out of the cell.

Key Terms

cell wall

a rigid cell covering made of cellulose in plants, peptidoglycan in bacteria, non-peptidoglycan compounds in Archaea, and chitin in fungi that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell

channel protein

membrane-spanning protein that has an inner pore which allows the passage of one or more substances

concentration gradient

a concentration gradient is present when a membrane separates two different concentrations of molecules

diffusion

movement of a substance from an area of higher concentration to one of lower concentration

facilitated diffusion

the spontaneous passage of molecules or ions down a concentration gradient across a biological membrane passing through specific transmembrane integral proteins

hypertonic

describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has higher osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell

hypotonic

describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has lower osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell; a cell in this environment causes water to enter the cell, causing it to swell

isotonic

describes a solution in which the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the fluid inside the cell

membrane protein

proteins that are attached to or associated with the membrane of a cell or an organelle

ligand

molecule that binds with specificity to a specific receptor molecule

osmolarity

the osmotic concentration of a solution, normally expressed as osmoles of solute per litre of solution; the total amount of substances dissolved in a specific amount of solution

osmosis

diffusion of water molecules down their concentration gradient across a selectively permeable membrane

passive transport

a method of transporting material across membranes that does not require cellular energy

peripheral protein

membrane-associated protein that does not span the width of the lipid bilayer, but is attached peripherally to integral proteins, membrane lipids, or other components of the membrane

receptor

protein molecule that contains a binding site for another specific molecule (called a ligand)

selective permeability

feature of any barrier that allows certain substances to cross but excludes others

semipermeable membrane

a type of biological membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by diffusion and occasionally by specialized facilitated diffusion

solute

any substance that is dissolved in a liquid solvent to create a solution

tonicity

the amount of solute in a solution

Long Descriptions

Figure 1 Image Description:

Passive transport includes:

- Simple diffusion:

- Gas or liquid medium transported.

- Requires a concentration gradient.

- Occurs in living and non-living systems.

- Ions cannot pass plasma membranes because they are repelled by hydrophobic tails (transport via facilitated diffusion).

- Facilitated diffusion:

- Similar to simple diffusion, but requires integral proteins (e.g., carrier and channel proteins).

- Protein size and shape determine the specific substance it can transport.

- Concentration gradient required.

- Transport substances too big for simple diffusion.

Active transport:

- Requires ATP (energy) to transport substances against concentration gradient.

- Proteins activated by ATP (breaks of phosphate) causing the protein to change shape to transport substance. Then, when ADP + Pi released, protein returns to its original state. [Return to Figure 1]

Figure 12 Image Description: The table below shows some key points in the graph. Note that fluctuations up and down exist in between these points.

| Amino Acid Numer (Window Size = 7) | Hydrophobicity |

|---|---|

| 3 | 1 |

| 27 | -1.2 |

| 51 | 0 |

| 75 | -1.9 |

| 99 | -0.3 |

| 123 | 1.4 |

| 147 | -1 |

| 171 | -1.3 |

| 195 | -0.8 |

| 219 | -0.2 |

| 242 | -0.4 |

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Passive vs Active Membrane Transport by LSumi (2022), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 7-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 7-2 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 3.22 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 3.23 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 7-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 5.9 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Sucrose porin 1a0s by Opabinia regalis (2007), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 5.10 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Scheme facilitated diffusion in cell membrane-en by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain

- Figure 11: Figure 7-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure: hydrophathy plot for chymotrypsinogen from Biochemistry Online (Jakubowski) (Jakubowski 2019) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Andrey K. Aquaporins [Video]. YouTube. 2015 May 6, 8:07 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFu86zguTZA.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2022. Anatomy and physiology 2e. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2022. Anatomy and physiology 2e. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 3.1: the cell membrane. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/3-1-the-cell-membrane.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2018. Clinical review report: lumacraftor/lvacaftor (orkambi): (Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Canada) Incorporated): indication: for the treatment of cystic fibrosis in patients aged six years and older who are homozygous for the F508del mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Appendix 8: Summary of F508del mutation testing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540352/.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figures 5.9, 5.10. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/5-2-passive-transport.

Cystic Fibrosis Canada. 2017. The Canadian cystic fibrosis registry. Toronto (ON): Cystic Fibrosis Canada. 2016 annual date report. [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://www.cysticfibrosis.ca/uploads/2016 Registry Annual Data Report.pdf.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/1-introduction.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figures 3.22, 3.23. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/3-5-passive-transport.

H Productions. Explaination of cell membrane 3d animation [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Nov 19, 4:33 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=78cjL-o2aoc.

Jakubowski H. 2019. Biochemistry online (Jakubowski). St. Joseph (MN): College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://chem.libretexts.org/Under_Construction/Purgatory/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Online_(Jakubowski).

Jakubowski H. 2019. Biochemistry online (Jakubowski). St. Joseph (MN): College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figure: hydrophathy plot for chymotrypsinogen. https://bio.libretexts.org/Under_Construction/Purgatory/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Online_(Jakubowski)/02%3A_PROTEIN_STRUCTURE/G._Predicting_Protein_Properties_From_Sequences/G3._Prediction_of_Hydrophobicity.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figures 7-1 to 7-3, 7-5. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/a762477a-0cf1-4ff5-ae0c-0a86c45ea15e.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Diffusion and passive transport. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jun 18]. AP®︎/College Biology, Lesson 6: facilitated diffusion. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/facilitated-diffusion/a/diffusion-and-passive-transport.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Facilitated diffusion [quiz]. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jun 28]. AP®︎/College Biology, Lesson 6: facilitated diffusion. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/facilitated-diffusion/e/facilitated-diffusion.

Khan Academy. Facilitated diffusion [Video]. Khan Academy. 2015 Jul 31, 6:34 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/facilitated-diffusion/v/facilitated-diffusion.

LSumi. 2022. Passive vs active membrane transport [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2022 May 18; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118132547.

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless).

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 5.6: passive transport – diffusion, Chapter 5.7: passive transport – facilitated transport, Chapter 5.8: passive transport – osmosis. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless).

NIH Center for Information Technology. Aquaporin water channels – from transfusion medicine to malaria [Video]. LabXchange. 2021 Jan 26, 57:37. [updated 2023 Jul 7, accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:6bf925c5:video:1.

PhET. 2020. Membrane channels [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:a93a50ef:lx_simulation:1.

Regalis O. 2007. Sucrose porin 1a0s [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2007 Mar 12; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1775139.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 5.2: passive transport. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/5-2-passive-transport.

Ssaucita. Aquaporins claymation project [Video]. YouTube. 2011 Nov 30, 1:52 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7EGPtMqZ7pY.

The Concord Consortium. 2020. Aquapores [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:6ee5f667:lx_simulation:1

The Concord Consortium. 2020. Diffusion across a semipermeable membrane [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:b336eb0e:lx_simulation:1.

Villarreal MR [LadyofHats]. 2007. Scheme facilitated diffusion in cell membrane-en [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2008 May 2; accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scheme_facilitated_diffusion_in_cell_membrane-en.svg,

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Membrane transport. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [accessed 2022 Jun 19]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Membrane_transport&oldid=1088585196.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Porin (protein). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [accessed 2022 Jun 29]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Porin_(protein)&oldid=1095439024.

feature of any barrier that allows certain substances to cross but excludes others

a method of transporting material across membranes that does not require cellular energy

area of high concentration adjacent to an area of low concentration

proteins that are attached to or associated with the membrane of a cell or an organelle

the spontaneous passage of molecules or ions down a concentration gradient across a biological membrane passing through specific transmembrane integral proteins

movement of a substance from an area of higher concentration to one of lower concentration

membrane-spanning protein that has an inner pore which allows the passage of one or more substances

diffusion of water molecules down their concentration gradient across a selectively permeable membrane

a type of biological membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by diffusion and occasionally by specialized facilitated diffusion

any substance that is dissolved in a liquid solvent to create a solution

the amount of solute in a solution

the osmotic concentration of a solution, normally expressed as osmoles of solute per litre of solution; the total amount of substances dissolved in a specific amount of solution

describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has lower osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell; a cell in this environment causes water to enter the cell, causing it to swell

describes a solution in which the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the fluid inside the cell

describes a solution in which extracellular fluid has higher osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell

a rigid cell covering made of cellulose in plants, peptidoglycan in bacteria, non-peptidoglycan compounds in Archaea, and chitin in fungi that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell

protein molecule that contains a binding site for another specific molecule (called a ligand)

molecule that binds with specificity to a specific receptor molecule