2.1 Membrane Structure & Composition

Introduction

A cell’s plasma membrane defines the boundary of the cell and determines the nature of its contact with the environment. Cells exclude some substances, take in others, and excrete still others, all in controlled quantities. Plasma membranes enclose the borders of cells, but rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic and constantly in flux. The plasma membrane must be sufficiently flexible to allow certain cells, such as red and white blood cells, to change shape as they pass through narrow capillaries. These are the more obvious functions of a plasma membrane. In addition, the surface of the plasma membrane carries markers that allow cells to recognise one another, which is vital as tissues and organs form during early development and later plays a role in the “self” versus “non-self” distinction of the immune response.

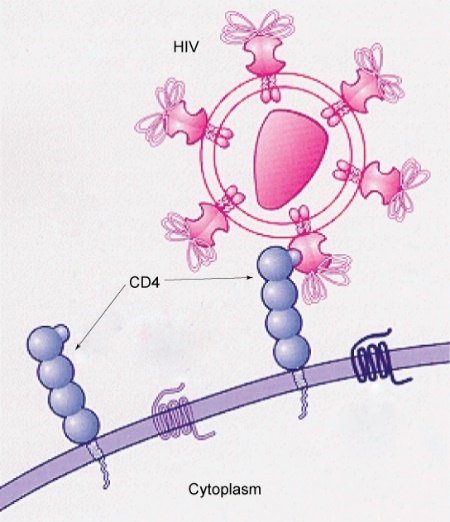

The plasma membrane also carries receptors, which are attachment sites for specific substances that interact with the cell. Each receptor is structured to bind with a specific substance. For example, surface receptors of the membrane create changes in the interior, such as changes in enzymes of metabolic pathways. These metabolic pathways might be vital for providing the cell with energy, making specific substances for the cell, or breaking down cellular waste or toxins for disposal. Receptors on the plasma membrane’s exterior surface interact with hormones or neurotransmitters and allow their messages to transmit into the cell. Viruses use some recognition sites as attachment points. Although receptors are highly specific, pathogens like viruses may evolve to exploit receptors to gain entry to a cell by mimicking the specific substance that the receptor is meant to bind. This specificity helps to explain why human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or any of the five types of hepatitis viruses or SARS-CoV-2 invade only specific cells.

Unit 2, Topic 1 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 2, Topic 1, you will be able to:

- Describe the fluid mosaic model of membranes.

- Describe the functions of phospholipids, proteins, and carbohydrates in membranes.

- Explain how membrane lipid and protein components and their structural asymmetries are important for membrane functions in cells.

- Compare the different ways in which proteins associate with cellular membranes.

- Predict how variation in the lipid composition of a membrane will affect its fluidity and the mobility of integral membrane proteins.

- Explain how cholesterol acts as a fluidity buffer and how it affects membrane permeability.

- Describe the function of cell surface glycoproteins and their relation to human health.

| Unit 2, Topic 1—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 2, Topic 1 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Fluid Mosaic Model. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Gorter and Grendal experiment. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane Fluidity. | 45 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Micelle Formation. | 30 |

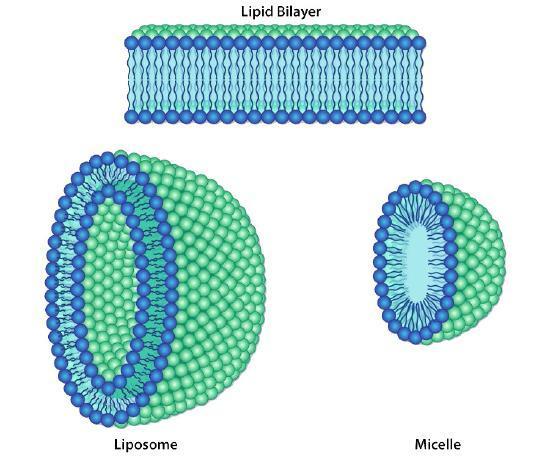

Lipid Bilayers

The protective membrane around cells contains many components, including cholesterol, proteins, glycolipids, phospholipids, and sphingolipids. The last two of these will, when mixed vigorously with water, spontaneously form what is called a lipid bilayer, which serves as a protective boundary for the cell that is largely impermeable to the movement of most materials across it. With the notable exceptions of water, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and oxygen, most polar/ionic molecules require transport proteins to help them navigate across the bilayer.

The orderly movement of these compounds is critical for the cell to be able to:

- Obtain food for energy

- Export materials

- Maintain osmotic balance

- Create gradients for transport

- Provide electromotive force for nerve signalling,

- Store energy in electrochemical gradients for ATP production (oxidative phosphorylation or photosynthesis).

Though some cells do not have cell walls (animal cells) and others do (bacteria, fungi, and plants), all cells possess plasma membranes. All plasma membranes have a lipid bilayer, each containing a significant number of amphiphilic molecules, including phospholipids and sphingolipids.

Components of Lipid Bilayers

Fatty acids

Unlike monosaccharides, nucleotides, and amino acids, fatty acids are not monomers linked together to form much larger molecules. Although fatty acids can link together (e.g., into triacylglycerols or phospholipids), they are not linked directly to one another, and there are generally no more than three in a given molecule. The fatty acids themselves are long chains of carbon atoms topped off with a carboxyl group. The chain length can vary, although most are between 14 and 20 carbons, and in higher-order plants and animals, fatty acids with 16 and 18 carbons are the major species.

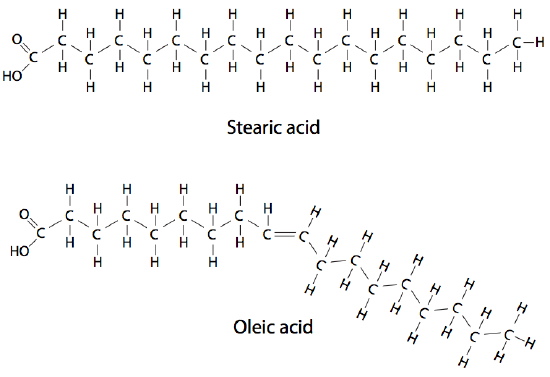

Due to the synthesis mechanism, most fatty acids have an even number of carbons, although odd-numbered carbon chains are possible. Double bonds between the carbons can generate more variety. Fatty acid chains with no double bonds are saturated because each carbon bonds to as many hydrogen atoms as chemically possible. Fatty acid chains with double or triple bonds are unsaturated (Figure 1). Those with more than one double or triple bond are called polyunsaturated. The fatty acids in eukaryotic cells contain nearly even amounts of saturated and unsaturated types; many of the latter may be polyunsaturated (Table 1).

| Table 1: Common fatty acids and their carbon chain length and number of C-C double bonds. (Adapted from Katzman et al. 2020/Fundamentals of Cell Biology) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | |

| Fatty Acid | Number of carbon atoms : Number of C-C double bonds |

| Myristic Acid | 14:0 (14 carbons, no C-C double bonds) |

| Palmitic Acid | 16:0 |

| Stearic Acid | 18:0 |

| Arachidic Acid | 20:0 |

| Palmitoleic Acid | 16:1 |

| Oleic Acid | 18:1 |

| Linoleic Acid | 18:2 |

| Arachidonic Acid | 20:4 |

There are significant physical differences between the saturated and unsaturated fatty acids simply due to the geometry of the double-bonded carbons. A saturated fatty acid is very flexible, with free rotation around all its C-C bonds. The usual linear diagrams and formulas depicting saturated fatty acids also explain the ability of saturated fatty acids to pack tightly together with very little intervening space. On the other hand, unsaturated fatty acids cannot pack as tightly because of the rotational constraint imposed by the double bond. The carbons cannot rotate around the double bond, which forms a “kink” in the chain.

Phospholipids

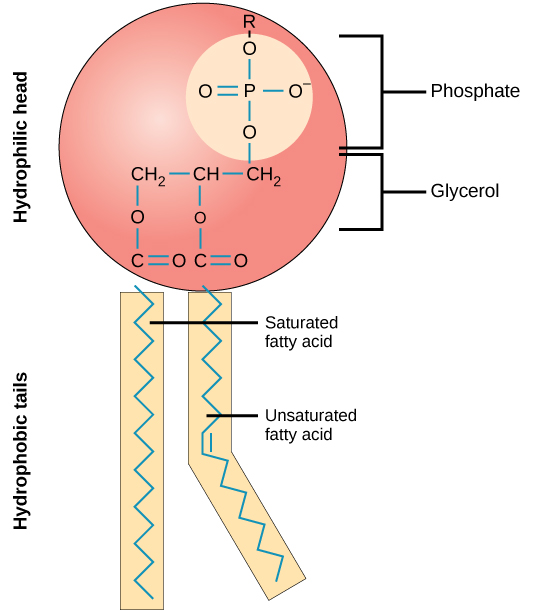

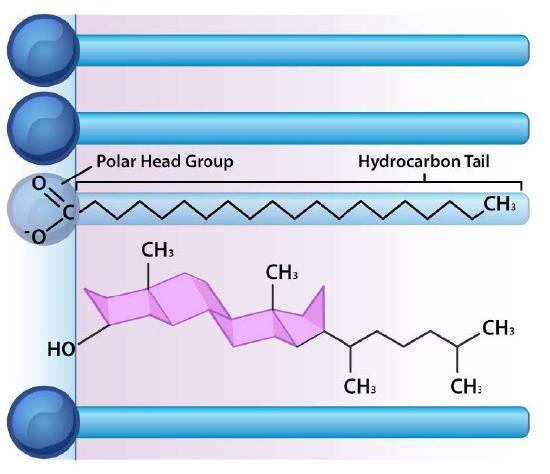

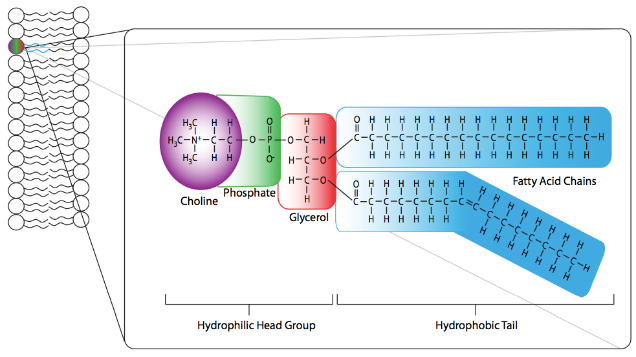

Phospholipids (also called phosphoglycerides or glycerophospholipids) are fatty acids attached to glycerol. However, instead of three fatty acid tails, there are only two, and a phosphate group is attached to the third carbon of the glycerol molecule (Figure 2). The phosphate group also links to a “head group.” The identity of the head group and the fatty acid tails name the molecule. Phospholipids are amphipathic. Amphipathic means that a structure is hydrophobic on one end and hydrophilic on the other. The fatty acid tails in a phospholipid are highly hydrophobic, while the head group is highly hydrophilic. The amphipathic nature of phospholipids plays a crucial part in their role as the primary component of cellular membranes.

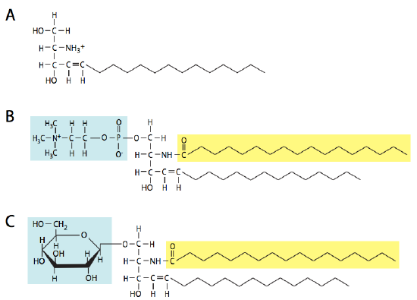

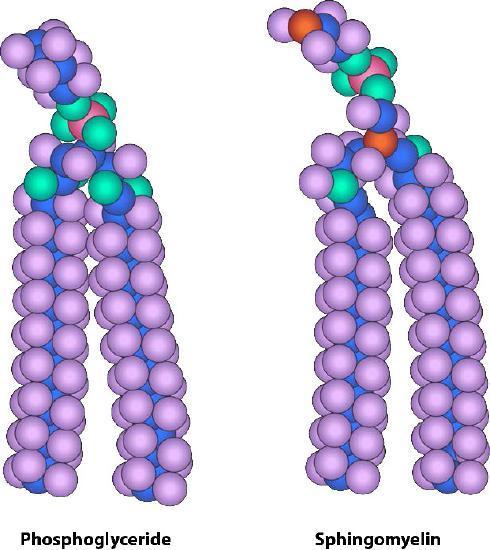

Sphingolipids (Figure 3 and Figure 4) are also important constituents of membranes. Instead of a glycerol backbone, their base is the amino alcohol, sphingosine (or dihydrosphingosine). There are four major types of sphingolipids: ceramides, sphingomyelins, cerebrosides, and gangliosides. Ceramides are sphingosine molecules with a fatty acid tail attached to the amino group. Sphingomyelins are ceramides in which a phosphocholine or phosphoethanolamine attaches to the 1-carbon. Cerebrosides and gangliosides are glycolipids with a single monosaccharide or multiple saccharides attached to the 1-carbon of a ceramide, respectively. The oligosaccharides attached to gangliosides all contain at least one sialic acid residue. In addition to being a structural component of the cell membrane,gangliosides play an important role in cell-to-cell recognition.

In each case, the phospholipid or sphingolipid has one polar and one nonpolar end. These amphiphilic molecules arrange themselves similarly to amino acids that tend to have their hydrophobic side chains on the inside of a folded protein to exclude water. This tendency of molecules, including proteins and phospholipid bilayers, to hide their hydrophobic regions is known as the hydrophobic effect. Remember that the cytoplasm of a cell contains a high percentage of water, and the exterior of the cell is also aqueous. It, therefore, makes perfect sense that the polar portions of the membrane molecules arrange themselves as they do — polar parts outside interacting with water and nonpolar parts in the middle of the bilayer avoiding/excluding water (Figure 5).

Folding of the Phospholipid Bilayer

Since most cells live in an aqueous environment and cell contents are mostly aqueous, it makes sense that a membrane that separates one side from the other must be hydrophobic to form an effective barrier against accidental leakage of materials or water. Cellular membranes are composed primarily of phospholipids. Phospholipids are molecules consisting of a phosphorylated polar head group attached to a glycerol backbone with two long hydrocarbon tails. The composition of the hydrocarbons varies in length, degree of saturation, and head group.

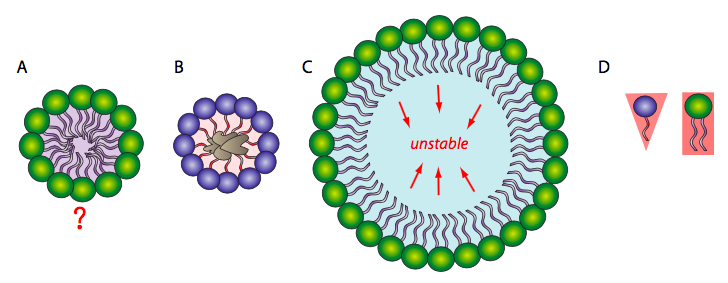

Because the phospholipids are amphipathic, the expected simplest conformation for a small group of phospholipids in an aqueous solution might be a micelle (Figure 6A), but is this the case? Mixtures of hydrophobic molecules and water are thermodynamically unstable, so a micelle would protect the hydrophobic fatty acid tails from the aqueous environment with which the head groups interact. Micelles can form with other amphipathic lipids, the most recognizable being detergents, like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (also called sodium lauryl sulfate), used in common household products, such as shampoos. Detergents surround hydrophobic dirt (Figure 6B) and hold it in solution within the micelle for water to rinse it away. At smaller sizes, the micelle is fairly stable; however, when there are a large number of phospholipids, the space inside the micelle becomes larger and can trap water in direct contact with the hydrophobic tails (Figure 6C), rendering the micelle unstable. Therefore, a single large phospholipid layer is unlikely to be stable enough to act as a biological membrane.

Additionally, micelles form easily with SDS and other single-tailed lipids because their overall shape (van der Waals envelope) is conical (Figure 6D), which lends itself to fitting tight curvatures. However, phospholipids are more cylindrical, which makes it harder to fit them into a tight spherical micelle. If they do form micelles, they tend to be larger and are likely to collapse.

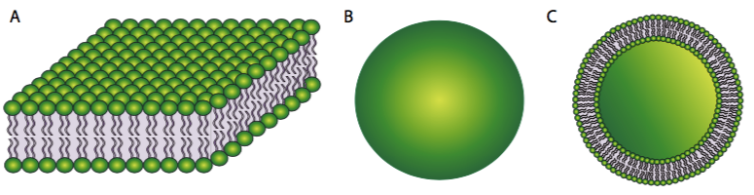

On the other hand, a phospholipid bilayer (Figure 7A) could form a fatty acid sandwich in which the polar head groups face outward to interact with an aqueous environment and the sequestered fatty acids in between. However, this does not resolve the problem on the edges of the sandwich. Therefore, the solution to the ideal phospholipid structure in an aqueous environment is a spherical phospholipid bilayer (Figure 7B and cutaway in Figure 7C): no edges mean no exposed hydrophobicity.

The stability of the spherical phospholipid bilayer does not imply that it is static in its physical properties. In most physiologically relevant conditions, the membrane is cohesive but fluid. It can mould its surface to the contours of whatever it is resting on, and the same thermodynamic and hydrophobic properties that make it so stable allow it to spontaneously seal up minor tears.

Self-Check

Why do phospholipids tend to spontaneously orient themselves into something resembling a membrane?

▼ Click to reveal answer

The hydrophobic, nonpolar regions must align with each other for the structure to have minimal potential energy and, consequently, higher stability. The fatty acid tails of the phospholipids cannot mix with water, but the phosphate “head” of the molecule can. Thus, the head orients to water and the tail to other lipids.

Learning Activity: Fluid Mosaic Model

In this activity, you will review aspects of the fluid mosaic model of the cell membrane.

- Watch ”Fluid Mosaic Model of the Cell Membrane” (1:25 min) by Wesley McCammon (2009).

- In your own words, describe what is wrong with the following statement:

“The cell membrane contains a phospholipid bilayer.”

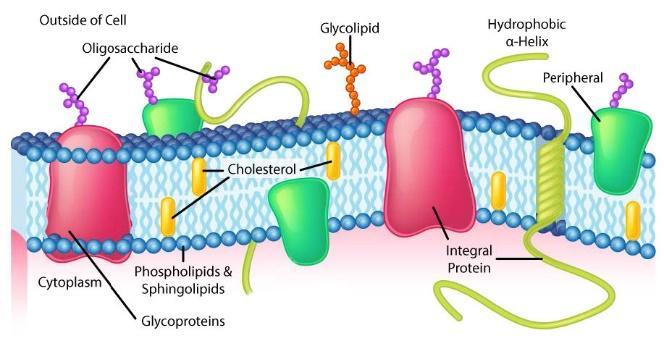

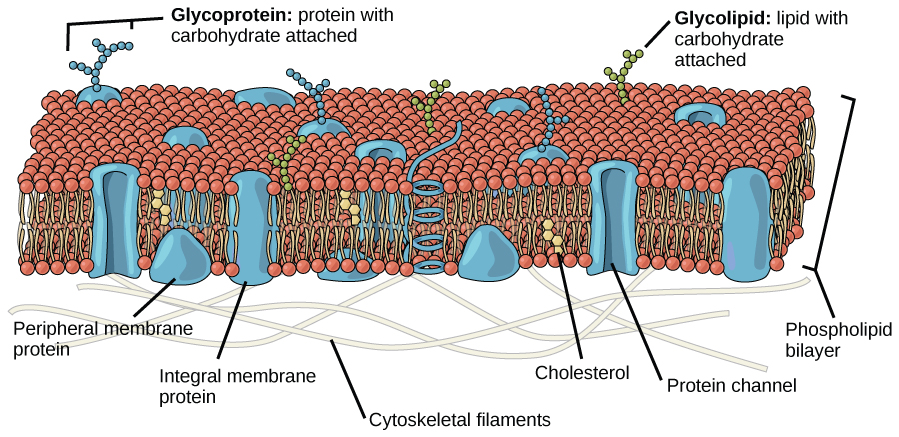

Composition Bias

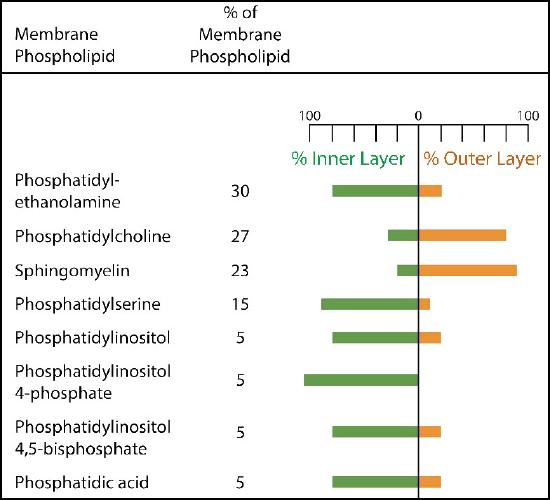

The composition of plasma membranes is different depending on their location. First, glycosylation (of lipids and proteins) has the sugar groups located almost exclusively on the outside of the cell, away from the cytoplasm (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Among the membrane lipids, sphingolipids are much more commonly glycosylated than phospholipids. Additionally, different types of phospholipids can be found preferentially on one side of the membrane or the other. Phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine are found preferentially within the inner leaflet (side) of the plasma membrane, whereas phosphatidylcholine tend to be located on the outer leaflet. Notably, in the process of apoptosis, phosphatidylserines flip to the outer leaflet, where they serve as a signal to macrophages to bind and destroy the cell. Sphingolipids are found preferentially in the plasma membrane and are almost completely absent from mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum membranes.

Diffusion of Lipids Within the Membrane

Lateral Diffusion

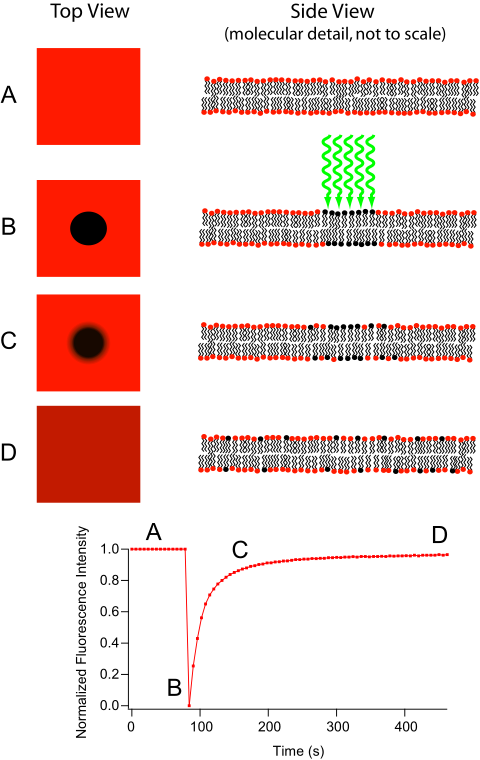

The movement of lipids within each leaflet (side) of the lipid bilayer occurs readily and rapidly due to membrane fluidity. This type of movement is called lateral diffusion and can be measured by a technique called fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) (Figure 10). In this method, a laser strikes and stains a section of the lipid bilayer of a cell, leaving a spot (shown in Figure 10B). Over time, the stain ultimately diffuses across the entire lipid bilayer, like a drop of ink added to a glass of water. A measurement of the diffusion rate indicates the fluidity of a membrane.

Transverse Diffusion

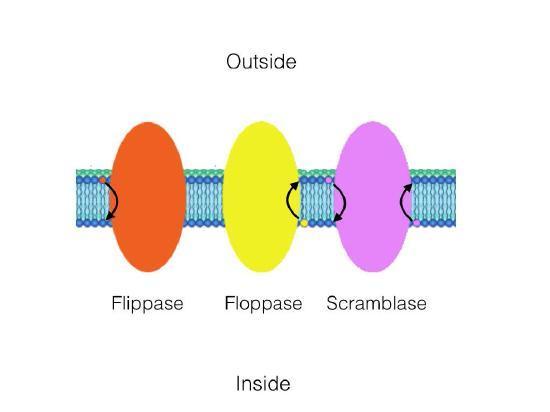

While the movement in lateral diffusion occurs rapidly, the movement of lipids from one leaflet over to the other occurs much more slowly or not at all. This type of molecular movement is called transverse diffusion and is almost nonexistent in the absence of enzyme action. Remember that there is a molecule distribution bias between membrane leaflets, which means that something must be organizing them.

Three enzymes catalyze the movement of compounds in transverse diffusion (Figure 11). Flippases move membrane glycerophospholipids/sphingolipids from the outer leaflet (extracellular space) to the inner leaflet (cytoplasmic side) of the cell. Floppases move membrane lipids in the opposite direction. Scramblases move them in either direction.

Other Components of the Lipid Bilayer

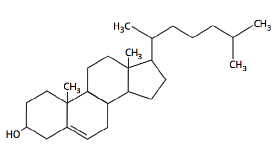

Besides phospholipids and sphingolipids, the lipid bilayer of cellular membranes commonly contains other materials. Two important and prominent ones are cholesterol (Figure 12) and proteins. Cholesterol is a saturated hydrocarbon consisting of four fused rings; the flatness and hydrophobicity of the sterol rings allow cholesterol to interact with the nonpolar portions of the lipid bilayer. In contrast, the hydroxyl group can interact with the hydrophilic part (Figure 13).

Membrane Fluidity

In 1972, S. J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson proposed a new plasma membrane model that, compared to earlier understanding, better explained microscopic observations and the function of the plasma membrane. This model is called the fluid mosaic model. The model has somewhat evolved over time, but it still provides the best illustration of the plasma membrane structure and functions as we now understand it. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components — including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates — in which the components can flow and change position while maintaining the basic integrity of the membrane. Both phospholipid molecules and embedded proteins can diffuse rapidly and laterally in the membrane. The fluidity of the plasma membrane is necessary for the activities of certain enzymes and transport molecules within the membrane. Plasma membranes range from 5–10 nm thick. As a comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8-µm thick, or approximately 1,000 times thicker than a plasma membrane.

Maintaining a working range of fluidity is important to the cell. If the membrane is too rigid, then it may be unable to move or undergo necessary processes such as endocytosis, in which a cell takes up large extracellular molecules by enveloping them with the cell membrane and pinching them off in a vesicle. On the other hand, if it becomes too fluid, it may fall apart. Although some phospholipids directly link to proteins and the cytoskeleton, most are not; therefore, they are free to move within the plane of their layer in the bilayer.

The following three major factors govern the fluidity of the plasma membrane:

- The degree of saturation and length of the fatty acid chains

- Temperature

- Cholesterol concentration

Because fully saturated fatty acid chains have no “kinks,” they can pack together very tightly, decreasing membrane fluidity. As more unsaturated fatty acid chains are added to the membrane, the kinks in their chains create more space between some of the fatty acid tails, increasing fluidity. Therefore, a membrane with more saturated fatty acid chains will have a more solid-like membrane, while a membrane with more unsaturated fatty acid chains will be more fluid-like. Similarly, at higher temperatures, even saturated fatty acid chains, with their increased energy, move more and create more space between the chains, increasing fluidity.

Finally, the structure of cholesterol is fantastic in that it allows both an increase and a decrease in membrane fluidity. Its ring structure is rigid (not freely rotatable), causing a reduction in molecular motion and decreasing membrane fluidity. However, the rings are also bulky, which increases the space around the cholesterol and allows for greater movement of neighbouring fatty acid chains; all these factors increase in membrane fluidity. The ability of cholesterol to increase and decrease fluidity is similar to a “buffer” for the membrane fluidity that helps prevent the membrane from becoming too fluid-like or solid-like.

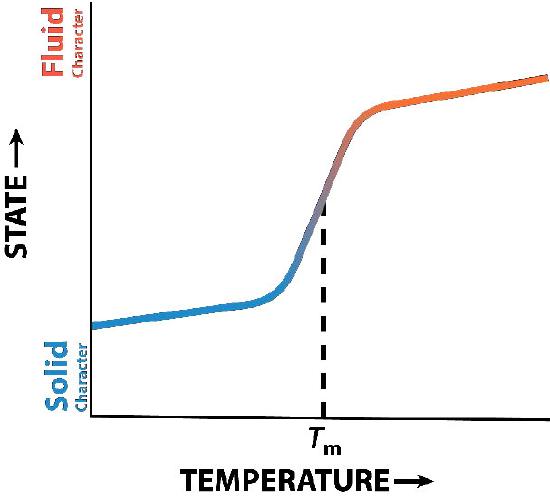

Cholesterol’s influence on membrane fluidity is complex. Figure 14 shows the phase transition for a membrane as it is heated, moving from a more “frozen” state to a more “fluid” one as the temperature rises. The mid-point of this transition, referred to as the Tm, is influenced by the fatty acid composition of the lipid bilayer compounds. Longer and more saturated fatty acids will favour higher Tm values, whereas unsaturation and short fatty acids will favour lower Tm values. This preference is why fish, which live in cool environments, have a higher level of unsaturated fatty acids; they use them to make membrane lipids that remain fluid at ocean temperatures. Interestingly, cholesterol does not change the Tm value but instead widens the transition range between frozen and fluid forms of the membrane, allowing it to have a wider range of fluidity.

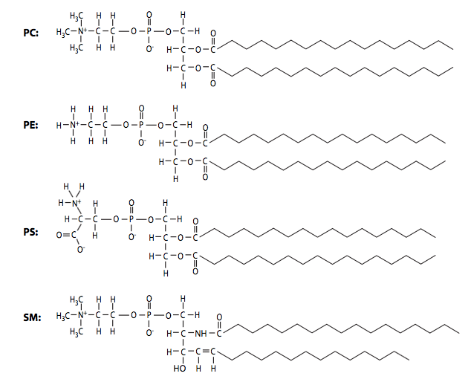

In addition to the three factors noted above, phospholipid composition can also alter membrane fluidity: shorter acid chains lead to greater fluidity. In comparison, longer chains, with more surface area for interaction, generate membranes with higher viscosity. The phospholipid composition of biological membranes is dynamic and varies widely. In Figure 15, the structures of the major phospholipid species phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), and sphingomyelin (SM) in plasma membranes from two different cell types. Due to their differing functions, the ratios of plasma membrane lipids of a myelinating Schwann cell are very different from lipids in the plasma membrane of a red blood cell.

However, some similarities exist between most eukaryotic membranes, such as the major component (~50%) phosphatidylcholine (PC) (Figure 16). Phosphatidylcholine structure consists of a choline molecule attached to the phosphate in the phospholipid structure. The fatty acid tails have one straight saturated and one bent unsaturated fatty acid. This bend generates space in the membrane and, therefore, increases fluidity. As the major component of most eukaryotic membranes, it ensures the overall ability of the membrane to maintain its structure and semi-permeable properties.

In addition, the mosaic characteristic of the membrane helps the plasma membrane remain fluid (Figure 17). The integral proteins and lipids exist in the membrane as separate but loosely attached molecules. The membrane is not like a balloon that can expand and contract; instead, it is fairly rigid and can burst if penetrated or if a cell takes in too much water. However, its mosaic nature means a very fine needle can easily penetrate a plasma membrane without causing it to burst; the membrane will flow and self-seal upon removal of the needle.

Unlike eukaryotes, bacterial membranes (with some exceptions, e.g., Mycoplasma and methanotrophs) generally do not contain sterols. However, many microbes contain structurally related compounds called hopanoids that likely fulfill the same function. Unlike eukaryotes, bacteria can have a wide variety of fatty acids within their membranes. Along with typical saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, bacteria can contain fatty acids with additional methyl, hydroxy or even cyclic groups. The bacterium can modulate the relative proportions of these fatty acids to maintain the optimum fluidity of the membrane (e.g., following temperature change).

Self-Check

Why is it advantageous for the cell membrane to be fluid in nature?

▼ Click to reveal answer

The fluid characteristic of the cell membrane allows greater flexibility to the cell than if the membrane were rigid. It also allows for motion in membrane components required for the activities of membrane enzymes and some types of membrane transport.

Lipid Rafts

Even within a single cell, the composition of the plasma membrane differs from that of intracellular organelles. Heterogeneity exists even within a membrane itself — the lipids are not distributed randomly in the membrane. Over the last two decades, research has identified lipid “rafts” that appear to have a specific role in embedding particular proteins. Since they are unanchored lipids, the rafts can move laterally within the membrane, just like most individual lipid molecules. Finally, the two layers of the bilayer have different ratios of the lipids. The cytoplasmic face of every membrane will have different associations and functions than the extracellular face.

In broad terms, the rafts are considered small areas of ordered lipids within a larger undirected membrane. A distinguishing feature of the rafts is that they are more ordered than the bilayer surrounding them; they contain more saturated fatty acids (tighter packing and less disorganization, as a result) and up to five times as much cholesterol as the bilayer (Figure 18). Additionally, they are relatively rich in sphingolipids, with as much as 50% greater quantities of sphingomyelin than surrounding areas of the bilayer. The higher cholesterol concentration in the rafts may be due to its greater ability to associate with sphingolipids (Figure 18).

Lipid rafts most often form in association with specific membrane proteins while excluding others. Usually, the included proteins have signalling-related functions, and one model proposes that these proteins may direct the organization of selected lipids around them rather than the other way around. Lipid rafts affect membrane fluidity, neurotransmission, and trafficking of receptors and membrane proteins.

Learning Activity: Gorter and Grendal experiment

- Watch the following videos:

- “Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent – Ethan Perlstein” (3:49 min) by TED-Ed (2013).

- “Langmuir Blodgett animation” (45 s) by MCeep (2013).

- Answer the following questions:

- Describe the purpose and hypothesis of their experiment.

- Describe the design of their experiment and its prediction.

- Describe the conclusions of their experiment.

- Use your knowledge of membrane composition to explain whether you agree with the conclusions of the Gorter and Grendal experiment.

- Why do you think Gorter and Grendal chose to extract lipids from mature RBCs (erythrocytes) and not from another cell type?

- Would you expect the extracted lipids to occupy a surface area twice that of an intact RBC outer surface? Can you directly compare the surface area of extracted lipids to an intact RBC outer surface area?

Learning Activity: Membrane Fluidity

This activity reviews the components that influence membrane fluidity.

- Watch a demonstration of the lipid bilayer fluidity using optical tweezers (Clarke et al. 2008):

- “Using Laser Tweezers for Manipulating Isolated Neurons InVitro” (10:47 min) by Educational Courses (2023).

- Watch and make notes on the following four videos. Each video describes various aspects of membranes and fluidity.

- “Fluid Mosaic Model of the Plasma Membrane – Phospholipid Bilayer” (7:10 min) by The Organic Chemistry Tutor (2019).

- “Cholesterol and the Cell Membrane” (2:34 min) by Sci-ology (2020).

- “Factors Influencing Membrane Fluidity” (1:36 min) by Gerry Bergtrom (2019).

- “Cholesterol and Fatty Acids Regulate Membrane Fluidity” (13:41 min) by Andrey K (2015).

- Answer the following questions:

- Describe the characteristics that affect hydrocarbon tail fluidity.

- Diagram how cholesterol acts as a fluidity buffer in the membrane of organisms that can regulate their internal temperature.

- Explain how organisms that do not have cholesterol can use homeoviscous adaptation to survive.

a. Look up poikilotherm and list which organisms use this adaptation; are any of these mammals? - Explain how cholesterol regulates membrane permeability.

- Describe one or two things you loved learning about membrane fluidity and permeability.

- Apply your knowledge of membrane fluidity by analyzing the data provided in the exercise below.

The number of C-C double bonds (unsaturation) in the hydrocarbon tails of the lipids composing cell membranes influences membrane fluidity. Fluidity depends on temperature and controls the transit of materials through the cell membrane. To maintain homeostasis, all organisms, including the simple bacterium E. coli, must sense the temperature in their environment and adapt to changes. Researchers grew samples of E. coli at four different temperatures and then determined the fatty acid composition of their plasma membranes.

The following table (Table 2) shows the data. U stands for unsaturated, and S stands for saturated.

Fatty acid compositions of the plasma membrane of E. coli were incubated at the temperatures shown in the table above. Myristic and palmitic acids are saturated, while palmitoleic and oleic acids each have one C-C double bond.

-

- Analyze the data to calculate the ratio of the fraction of unsaturated (U) to the fraction of saturated (S) fatty acids in the plasma membrane and complete the last row of the table.

- Graph the ratio U/S versus growth temperature.

- Explain the response of E. coli to the temperature of the environment.

- E. coli senses the temperature of its environment through the temperature-dependent confirmation of enzymes that convert a single bond in the lipid tail to a double bond and vice versa. Explain how the discovery of a mutant strain of E. coli could lead to this insight.

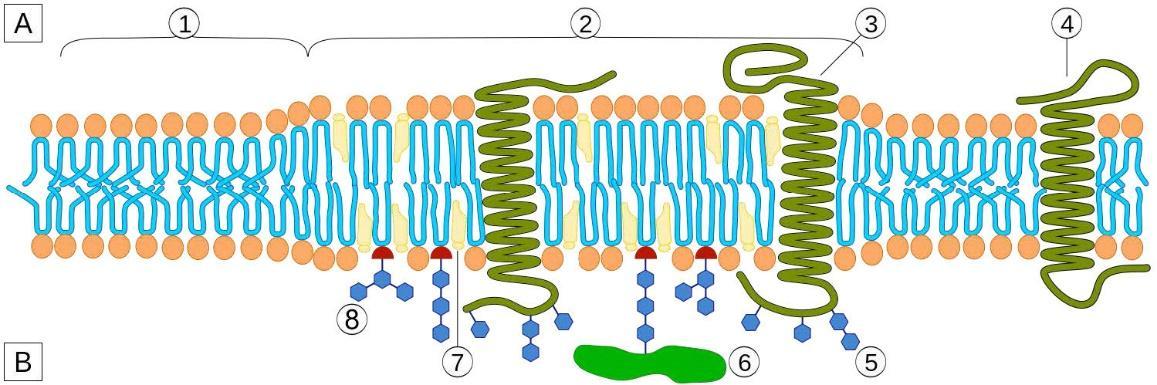

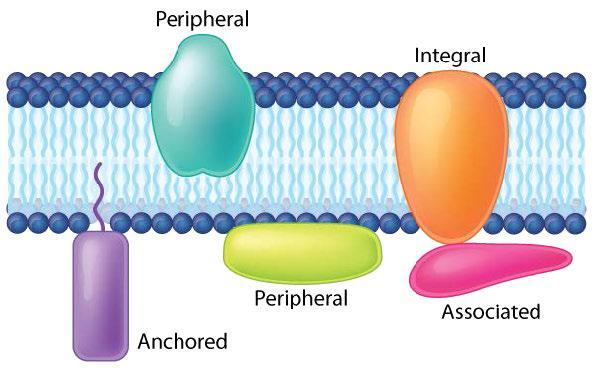

Membrane Proteins

Proteins make up the second major component of plasma membranes. Proteins in a lipid bilayer can vary in quantity enormously, depending on the membrane. Protein content by weight of various membranes typically ranges between 30% and 75% by weight. Some mitochondrial membranes can have up to 90% protein. Proteins linked to and associated with membranes come in several types. There are two main categories of membrane proteins: integral and peripheral.

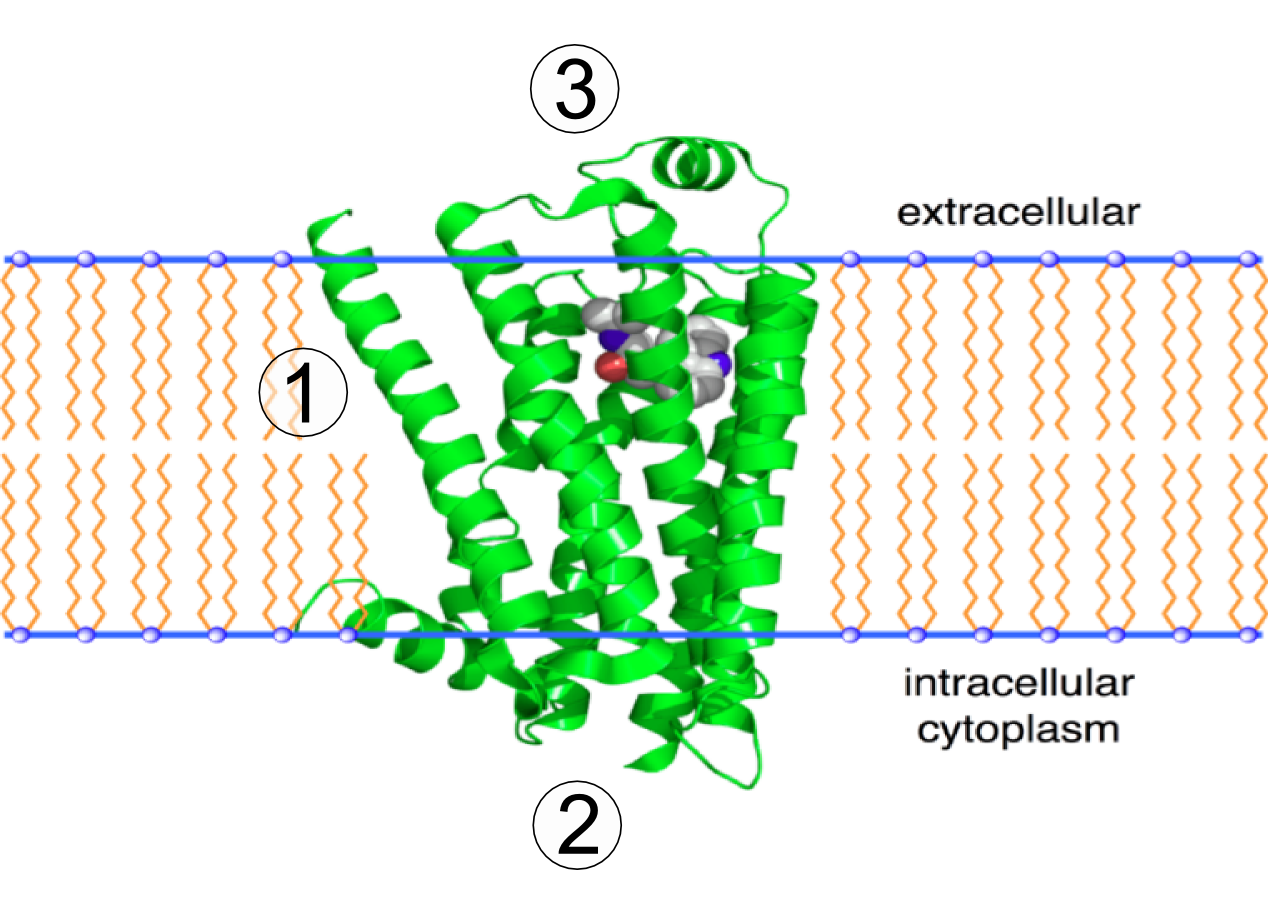

Before discussing membrane proteins, it is important to review protein structure and predict what chemical properties would allow them to associate with a cell membrane.

Self-Check

The size (length) and specific amino acid sequence of a protein are major determinants of its shape; the shape of a protein is critical to its function. These characteristics also influence how and whether a protein can associate with a biological membrane.

Go to Section 3.4 “Proteins” in the Biology for AP Courses textbook. Review amino acid structure, the chemical structures of proteins, and the levels of protein structure. The figure below shows the 3D structure of the integral membrane beta-2 adrenergic receptor. Use Figure 19 to answer the following questions.

Transmembrane Proteins

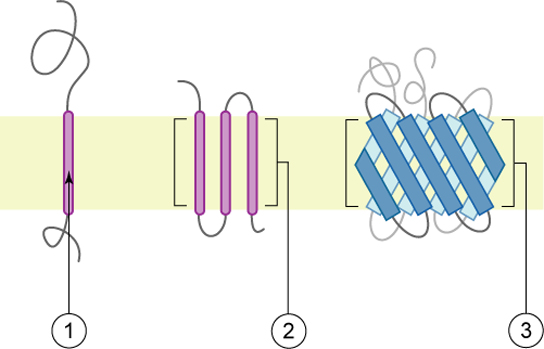

Transmembrane proteins are integral membrane proteins that span from one side of a biological membrane to the other and are firmly embedded in the membrane (Figure 20). Transmembrane proteins can function as docking sites for attachment (e.g., to the extracellular matrix), as receptors in the cellular signalling system, or facilitate the specific transport of molecules into or out of the cell (see Evolution Connection below).

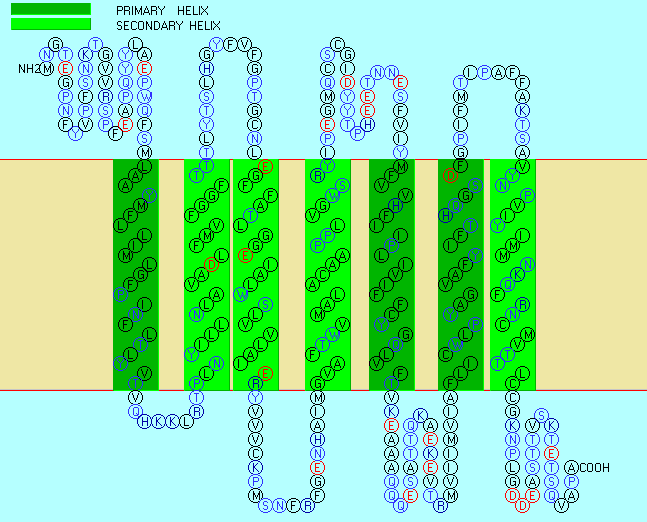

As their name suggests, integral proteins (some specialized types are called integrins) integrate completely into the membrane structure, and their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interact with the hydrophobic region of the phospholipid bilayer (Figure 21). Single-pass integral membrane proteins usually have a hydrophobic transmembrane segment with 20 to 25 amino acids. Some span only part of the membrane — associating with a single layer — while others stretch from one side of the membrane to the other with either side exposed. Some complex proteins are composed of up to 12 segments of a single protein, which are extensively folded and embedded in the membrane. This type of protein has a hydrophilic region or regions and one or several mildly hydrophobic regions. This region arrangement of the protein tends to orient the protein alongside the phospholipids, with the hydrophobic region of the protein adjacent to the tails of the phospholipids and the hydrophilic region or regions of the protein protruding from the membrane and in contact with the cytosol or extracellular fluid.

In all cases, the portion within the lipid bilayer consists primarily of hydrophobic amino acids. These are usually arranged in an alpha-helix so that the polar -C=O and -NH groups at the peptide bonds can interact with each other rather than with their hydrophobic surroundings. Therefore, integral membrane proteins can only be separated from the membranes using detergents (such as sodium dodecyl sulfate or SDS), nonpolar solvents, or sometimes denaturing agents. The portions of the polypeptide that project out from the bilayer tend to have a high percentage of hydrophilic amino acids. Furthermore, those that project into the aqueous surroundings of the cell are usually glycoproteins, with many hydrophilic sugar residues attached to the part of the polypeptide exposed at the surface of the cell. Some transmembrane proteins that span the bilayer several times form a hydrophilic channel through which certain ions and molecules can enter (or leave) the cell (see Unit 2, Topic 2).

Examples of integrated/transmembrane proteins include those involved in transport (e.g., Na+/K+ ATPase), ion channels (e.g., potassium channels of nerve cells), and signal transduction across the lipid bilayer (e.g., G-protein-coupled receptors). These will be discussed in further detail later on in this course.

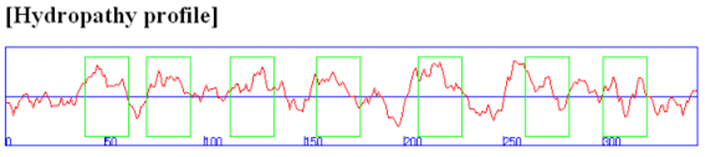

Transmembrane helices are visible in structures of membrane proteins determined by X-ray crystallography. Hydrophobicity scales can also predict them. Because the interior of the bilayer and the interiors of most known protein structures are hydrophobic, amino acids spanning a membrane are presumed to also require hydrophobicity. However, membrane pumps and ion channels also contain numerous charged and polar residues within the generally nonpolar transmembrane segments (see Unit 2, Topic 2 and Unit 2, Topic 3).

In some of these integral membrane proteins, large extracellular and intracellular domains are present and connected by the intramembrane regions. The intramembrane spanning region often consists of either a single alpha-helix or multiple different helical regions, which zig-zag through the membrane. Hydropathy calculations can readily determine these transmembrane sequences. For example, consider the hydropathy plot of the integral membrane bovine protein rhodopsin (Figure 22). The plot has the amino acid sequence of a protein on its x-axis and the degree of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity on its y-axis. There are several methods to measure the degree of polar solvent interaction, such as water with specific amino acids. Analyzing the shape of the plot gives information about the partial structure of the protein. For instance, if a stretch of about 20 amino acids shows positive for hydrophobicity, these amino acids may be part of an alpha-helix spanning across the lipid bilayer; they would be above the horizontal line shown by the arrow in Figure 22. Conversely, amino acids with high hydrophilicity indicate that these residues are in contact with solvent (e.g., water) and, therefore, likely to reside on the outer surface of the protein. In overall topology, these amino acids would reside in the extracellular or intracellular regions.

Integral membrane proteins can be released from the membrane and effectively solubilized by adding single-chain amphiphiles (detergents), which form a mixed micelle with the integral membrane protein. Mixed micelle forms when nonpolar tails in detergents interact with the hydrophobic transmembrane domain in the membrane protein. Studying membrane proteins in a more natural environment can involve reconstituting proteins solubilized by nonionic detergent into bilayer liposome structures. Nonionic detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, octylglucoside) are often used to purify membrane proteins in their natural state. Not only do ionic detergents (like SDS) solubilize integral membrane proteins, but they can also denature them.

Self-Check

Glycocalyx

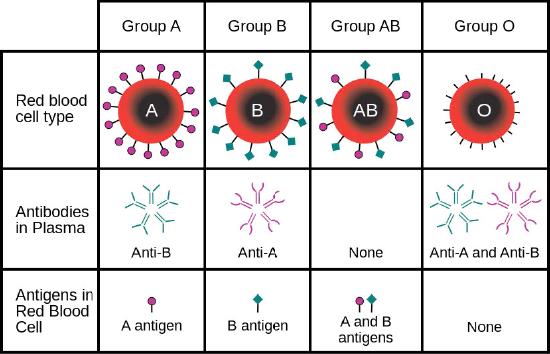

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound to either proteins (forming glycoproteins) or lipids (forming glycolipids). These carbohydrate chains may consist of two to 60 monosaccharide units and can be either straight or branched. Carbohydrate components of glycosylated membrane proteins inform their function. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognise each other. This recognition function is very important to cells, as it allows the immune system to differentiate between body cells (called “self”) and foreign cells or tissues (called “non-self”). Similar types of glycoproteins and glycolipids are found on the surfaces of viruses and may change frequently, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them (see Evolution Connection below). Glycoproteins also enable specific interactions of cells with each other to form tissues.

These carbohydrates on the exterior surface of the cell — the carbohydrate components of both glycoproteins and glycolipids — are collectively referred to as the glycocalyx (meaning “sugar coating”). The glycocalyx is highly hydrophilic and attracts large amounts of water to the surface of the cell. This function aids in the interaction of the cell with its watery environment and its ability to obtain substances dissolved in the water.

Cells have hundreds to thousands of membrane proteins, and the protein composition of a membrane varies with its function and location. Glycoproteins embedded in membranes play important roles in cellular identification. Blood types, for example, differ from each other in the structure of the carbohydrate chains projecting out from the surface of the glycoprotein in their membranes (Figure 23).

Evolution Connection: How Viruses Infect Specific Organs

Many viruses infect specific organs by exploiting specific glycoprotein molecules exposed on the surface of the cell membranes of host cells. For example, HIV can penetrate the plasma membranes of certain white blood cells (called T-helper cells and monocytes) and some cells in the central nervous system. Meanwhile, the hepatitis virus only attacks liver cells.

These viruses can invade these cells because the cells have binding sites on their surfaces that the viruses have exploited with equally specific glycoproteins in their coats (Figure 24). The cell is tricked by the mimicry of the virus coat molecules, allowing the virus to enter the cell.

Other recognition sites on the virus’s surface interact with the human immune system, prompting the body to produce antibodies. The human body makes antibodies in response to the antigens or proteins associated with invasive pathogens. These same sites serve as places for antibodies to attach and either destroy or inhibit the activity of the virus. Unfortunately, the genes that encode these sites on HIV change quickly, making the production of an effective vaccine against the virus very difficult.

The virus population within an infected individual quickly evolves through mutation into different populations, or variants, distinguished by differences in these recognition sites. This rapid change of viral surface markers decreases the effectiveness of the person’s immune system in attacking the virus because the antibodies will not recognise the new surface pattern variations.

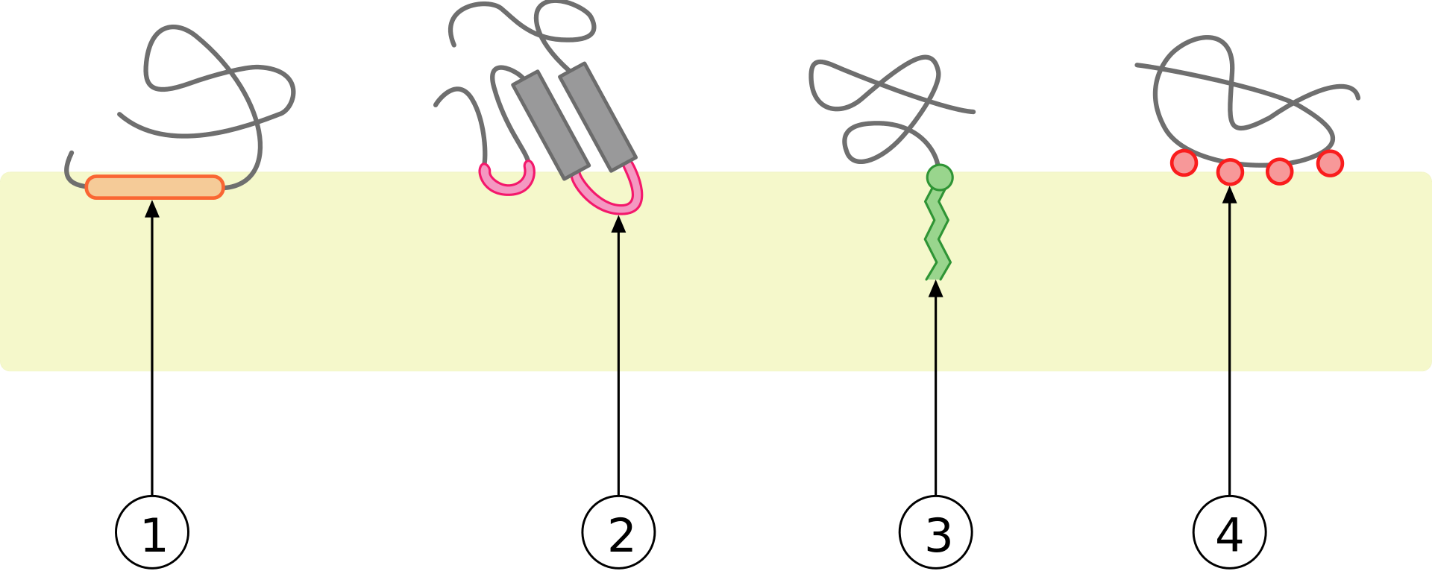

Peripheral Membrane Proteins

Peripheral membrane proteins are more loosely associated with the membrane and interact with a part of the bilayer (usually not involving hydrophobic interactions) but do not project through it (Figure 20 and Figure 25). Associated membrane proteins typically do not have external hydrophobic regions, so they cannot embed in a portion of the lipid bilayer, and they are usually noncovalently attached to the protruding portions of integral membrane proteins (Figure 20 and Figure 25-4). Such associations may arise from interactions with other proteins or molecules in the lipid bilayer. In contrast to integral membrane proteins, peripheral membrane proteins tend to collect in the water-soluble component or fraction of all the proteins extracted during a protein purification procedure.

Anchored membrane proteins are not embedded in the lipid bilayer; instead, they covalently attach to a molecule (typically a fatty acid) embedded in the membrane (Figure 25-3). These proteins insert themselves and assume a place alongside the similar fatty acid tails in the bilayer structure of the membrane. The lipid-anchored protein can be located on either side of the cell membrane. Thus, the lipid serves to anchor the protein to the cell membrane. Lipid-anchored proteins are covalently attached to different fatty acid acyl chains on the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane via palmitoylation, myristoylation or prenylation.

On the exoplasmic face of the cell membrane, lipid-anchored proteins covalently attach to the lipids glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) and cholesterol. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol attaches to the C-terminus of a protein during posttranslational modification in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in a GPI-anchored protein. Phospholipase C (PLC) is an enzyme known to cleave the phospho-glycerol bond found in GPI-anchored proteins. Detergents cannot remove GPI-anchored proteins, so releasing GPI-linked proteins from the outer cell membrane requires treatment with PLC.

Membrane proteins are often restricted in their movements. Since a lipid bilayer is a film of oil, the structures immersed in it may be expected to be relatively free to float about. For some membrane proteins, this is the case. For others, however, their mobility is limited as follows:

- Some proteins exposed at the interior face of the plasma membrane are tethered to cytoskeletal elements (e.g., actin microfilaments).

- Some proteins at the exterior face of the plasma membrane are anchored to components of the extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen).

- Integral membrane proteins cannot pass through the tight junctions found between some kinds of cells (e.g., epithelial enterocyte cells).

Learning Activity: Micelle Formation

This activity reviews the aspects of micelle formation and how detergents interact with biological membranes.

- Watch the following video tutorials:

- “SDS and Biological Membranes” (2:52 min) video animation by LabXchange (2020).

- “Which is better: Soap or hand sanitizer? – Alex Rosenthal and Pall Thordarson” (6:14 min) by TED-Ed (2020).

- “Why don’t oil and water mix? – John Pollard” (5:02 min) by TED-Ed (2013).

- Answer the following questions:

- Using proper terminology, explain the difference between a micelle and a phospholipid bilayer; incorporate aspects of the hydrophobic effect.

- Explain how detergents break open phospholipid bilayers.

- Explain how detergents are used to isolate integral membrane proteins. Draw a diagram to illustrate this.

- Would you use a detergent to remove a GPI-anchored membrane protein? Explain.

- How does hand washing relate to biological membranes, viral diversity and health?

- What lecture learning objective(s) relate to this content?

- What are one or two things that YOU loved learning from these videos?

Key Concepts and Summary

- The modern understanding of the plasma membrane is the fluid mosaic model.

- The plasma membrane is composed of a bilayer of phospholipids, with their hydrophobic, fatty acid tails touching each other.

- Proteins stud the landscape of the membrane, some of which span the membrane.

- Cells have hundreds to thousands of membrane proteins, and the protein composition of a membrane varies with its function and location; some proteins transport materials into or out of the cell.

- Carbohydrates are attached to some of the proteins and lipids on the outward-facing surface of the membrane, forming complexes that identify the cell from other cells.

- The fluid nature of the membrane is due to temperature, the configuration of the fatty acid tails (some kinked by double bonds), the presence of cholesterol embedded in the membrane, and the mosaic nature of the proteins and protein-carbohydrate combinations (not firmly fixed in place).

- Plasma membranes enclose and define the borders of cells; rather than being a static bag, they are dynamic and constantly in flux and have the following characteristics, summarized in Table 3:

- The main fabric of the membrane is composed of amphiphilic or dual-loving phospholipid molecules.

- Integral proteins, the second major component of plasma membranes, integrate completely into the membrane structure with their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interacting with the hydrophobic region of the phospholipid bilayer.

- Carbohydrates, the third major component of plasma membranes, are always found on the exterior surface of cells, where they are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or lipids (forming glycolipids).

- Glycoproteins embedded in membranes play important roles in cellular identification. They allow interactions with extracellular surfaces to which they must adhere, and they play an important role as part of receptors for many hormones and other chemical communication biomolecules.

Key Terms

amphiphilic/amphipathic

molecule possessing a polar or charged area and a nonpolar or uncharged area capable of interacting with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments

cell membrane

specialized structure that surrounds the cell and its internal environment; controls movement of substances into/out of cell

fluid mosaic model

describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, glycoproteins, and glycolipids (sugar chains attached to proteins or lipids, respectively), resulting in a fluid character (fluidity)

glycocalyx

coating of sugar molecules that surrounds the cell membrane

glycolipid

combination of carbohydrates and lipids

glycoprotein

combination of carbohydrates and proteins

hydrophilic

molecule with the ability to bond with water; “water-loving”

hydrophobic

molecule that does not have the ability to bond with water; “water-fearing”

integral protein

protein integrated into the membrane structure that interacts extensively with the hydrocarbon chains of membrane lipids and often spans the membrane; these proteins can be removed only by the disruption of the membrane by detergents

peripheral protein

protein found at the surface of a plasma membrane either on its exterior or interior side; these proteins can be removed (washed off of the membrane) by a high-salt wash

phospholipid

amphipathic lipid made of glycerol, two fatty acid tails, and a phosphate group

phospholipid bilayer

a biological membrane involving two layers of phospholipids with their tails pointing inward

plasma membrane

a phospholipid bilayer with embedded (integral) or attached (peripheral) proteins that separates the internal contents of the cell from its surrounding environment

saturated fatty acid

long-chain of hydrocarbon with single covalent bonds in the carbon chain; the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon skeleton is maximized

semi-permeable membrane

membrane that allows certain substances to pass through

steroid

type of lipid composed of four fused hydrocarbon rings forming a planar structure

triacylglycerol (also triglyceride)

fat molecule; consists of three fatty acids linked to a glycerol molecule

unsaturated fatty acid

long-chain hydrocarbon that has one or more double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain

X-ray crystallography

an experimental procedure to determine the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal. The crystalline structure causes a beam of X-rays to diffract into many different directions. The angles of the diffracted beams are measured to produce a 3-dimensional image

Long Descriptions

Figure 8 Image Description: The cell membrane is lined on both sides with phospholipids and sphingolipids. Inside the membrane, there is cholesteral. Integral proteins, like glycoproteins and hydrophobic a-helix, stick out on both sides of the membrane. Peripheral proteins only stick out of one side of the membrane. Outside the cell, oligosaccharides attach to proteins, and glycolipids attach to the cell membrane. [Return to Figure 8]

Figure 9 Image Description: The breakdown of molecular differential distributions of membrane lipids in inner and outer leaflet is as follows:

- Phosphatidyl-ethanolamine – 30% – 80% inner, 20% outer.

- Phosphatidylcholine – 27% – 30% inner, 70% outer.

- Sphingomyelin – 23% – 20% inner, 80% outer.

- Phosphatidylserine – 15% – 90% inner, 10% outer.

- Phoshatidylinositol – 5% – 80% inner, 20% outer.

- Phoshatidylinositol 4-phosphate – 5% – 100% inner.

- Phoshatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate – 5% – 80% inner, 20% outer.

- Phosphatidic acid – 5% – 80% inner, 20% outer. [Return to Figure 9]

Figure 10 Image Description: Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching is divided into four stages:

- The original state of the membrane:

- Diagram – the top view is a red square. The side view is the normal lipid bilayer.

- Graph – the normalized fluorescence intensity is one at zero seconds.

- The laser hits the lipid bilayer:

- Diagram – the top view is a red square with a black dot in the middle. The side view shows the laser hitting and staining the lipid bilayer.

- Graph – the normalized fluorescence intensity is zero at 90 seconds.

- Stain starts to diffuse:

- Diagram – the top view is a red square with a blurry black dot in the middle. The side view shows the stain beginning to diffuse to the sides.

- Graph – the normalized fluorescence intensity is 0.8 at 150 seconds.

- The stain is completely diffused:

- Diagram – the top view is a darker red square with no dot. The side view shows the stain diffused evenly throughout the membrane.

- Graph – the normalized fluorescence intensity is 0.9 at 500 seconds.

Figure 16 Image Description: Phosphatidylcholine have a hydrophilic head group made up of choline, phosphate, and glycerol. The hydrophobic tail is made of one saturated and one unsaturated fatty acid chain. [Return to Figure 16]

Figure 17 Image Description: Outside the membrane are glycoproteins (proteins with a carbohydrate attached) and glycolipids (lipids with a carbohydrate attached). Within the membrane are protein channels, cholesterol, integral membrane proteins, and peripheral membrane proteins. Inside the cell are cytoskeletal filaments. [Return to Figure 17]

Figure 20 Image Description: Anchored proteins are attached to the membrane by a “tail.” Peripheral proteins can be partially embedded or along the side of the membrane. Integral proteins are embedded in the membrane and stick out on both sides. Associated proteins attach to other proteins embedded in the membrane. [Return to Figure 20]

Figure 23 Image Description: Blood types have the following characteristics:

- Group A has anti-B antibodies in the plasma with A antigens on the red blood cells.

- Group B has anti-A antibodies in the plasma with B antigens on the red blood cells.

- Group AB has no antibodies in the plasma with A and B antigens on the red blood cells.

- Group O has anti-A and anti-B antibodies in the plasma with no antigens on the red blood cells.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 6-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 6-2 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 6-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 6-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 6-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 6-6 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 6-7 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 6-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 3.7 by Pehr Jacobson, from Biochemistry Free for All (Ahern, Rajagopal, and Tan) (Ahern et al. 2021), is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 3.10 from Biochemistry Free for All (Ahern, Rajagopal, and Tan) (Ahern et al. 2021) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: Figure 6-9 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 6-10 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 6-11 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: Figure 3.14 by Aleia Kim, from Biochemistry Free for All (Ahern, Rajagopal, and Tan) (Ahern et al. 2021), is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Figure 6-12 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 16: Figure 6-13 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 17: Figure 6-14 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 18: Figure 6-15 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 19: 2RH1 by Boghog (2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 20: Figure 6-16 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 21: Figure 5.2.1 from General Biology (Boundless) (LumenLearning 2023) is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 22: Figure: seven transmembrane helics from Biochemistry Online (Jakubowski) (Jakubowski 2019) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 23: ABO blood type by InvictaHOG (2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 24: Figure 3.19 [modification of work by US National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 25: Monotopic membrane protein by Foobar (2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

References

Ahern K, Rajagopal I, Tan T. 2021. Biochemistry free for all (Ahern, Rajagopal, and Tan). Corvallis (OR): Oregon State University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Biochemistry/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Free_For_All_(Ahern_Rajagopal_and_Tan).

Ahern K, Rajagopal I, Tan T. 2021. Biochemistry free for all (Ahern, Rajagopal, and Tan). Corvallis (OR): Oregon State University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figures 3.7, 3.10, 3.14. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Biochemistry/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Free_For_All_(Ahern_Rajagopal_and_Tan)/03%3A_Membranes/3.01%3A_Basic_Concepts_in_Membranes.

Andrey K. Cholesterol and fatty acids regulate membrane fluidity [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Apr 30, 13:41 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wnBTZ02wnAE.

Boghog. 2007. 2RH1 [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2018 Jul 5; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2RH1.png .

Clarke R, Wang J, Townes-Anderson E. 2008. Using laser tweezers for manipulating isolated neurons in vitro. J Vis Exp. (14):e911. https://www.jove.com/t/911/using-laser-tweezers-for-manipulating-isolated-neurons-in-vitro. doi: 10.3791/911.

Educational courses. Using lazer tweezers for manipulating isolated neurons in vitro [Video]. YouTube. 2023 Feb 19, 10:47 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPCNx4XR5F4.

Foobar. 2006. Monotopic membrane protein [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2008 Apr 10; accessed 2024 Jan 23]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monotopic_membrane_protein.svg.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/1-introduction.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 3.19. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/3-4-the-cell-membrane.

Gerry Bergtrom. 284-2 factors influencing membrane fluidity [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Apr 15, 1:36 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jqG6Rrts0CY.

InvictaHOG. 2006. ABO blood type [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2022 Feb 12; accessed 2024 Jan 23]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ABO_blood_type.svg.

Jakubowski H. 2019. Biochemistry online (Jakubowski). St. Joseph (MN): College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://chem.libretexts.org/Under_Construction/Purgatory/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Online_(Jakubowski).

Jakubowski H. 2019. Biochemistry online (Jakubowski). St. Joseph (MN): College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. G4: prediction of membrane protein structure. https://chem.libretexts.org/Under_Construction/Purgatory/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Online_(Jakubowski)/04%3A_Protein_Structure/4.7%3A_G._Predicting_Protein_Properties_From_Sequences/G4._Prediction_of_Membrane_Protein_Structure.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figures 6-1 to 6-16. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/63bdf811-2ef8-41c1-a07b-ef62d182b7f1.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. The cell membrane review. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jun 18]. AP®︎/College Biology, Lesson 3: plasma membranes. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/plasma-membranes/a/hs-the-cell-membrane-review.

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball).

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 3.2: cell membranes. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball)/03%3A_The_Cellular_Basis_of_Life/3.02%3A_Cell_Membranes.

LabXchange. SDA and biological membranes [Video]. LabXchange. 2020 Jan 21. 2:52 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:8e30eeab:video:1?source=%2Flibrary%2Fclusters%2Flx-cluster%3AIntroBio.

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless).

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figure 5.2.1. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless)/05%3A_Structure_and_Function_of_Plasma_Membranes/5.02%3A_Components_and_Structure_-_Fluid_Mosaic_Model.

MCeeP. Langmuir blodgett animation [Video]. YouTube. 2013 May 15, 0:45 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8yqyRr2VQg.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 5.1: components and structure. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/34-1-digestive-systems.

Sci-ology. Cholesterol and the cell membrane | cell biology [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Oct 25, 2:34 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Q-Tz30pz18.

TED-Ed. Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent – Ethan Perlstein [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Feb 26, 3:49 minnutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAXnYcUjn5k.

TED-Ed. Why don’t oil and water mix? – John Pollard [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Oct 10, 5:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5yIJXdItgo.

TED-Ed. Which is better: soap or hand sanitizer? – Alex Rosenthal and Pall Thordarson [Video]. YouTube. 2020 May 5, 6:14 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7KKkElpyKQ.

The Organic Chemistry Tutor. Fluid mosaic model of the plasma membrane – phospholipid bilayer [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Oct 15, 7:10 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQjzPZZ4olE.

Wesley McCammon. Fluid model of the cell membrane [Video]. YouTube. 2009 Jul 19, 1:26 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKN5sq5dtW4.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Bacterial cell structure. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2022 Apr 30; accessed 2022 Jun 18]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bacterial_cell_structure&oldid=1085458364.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Hydrophilicity plot. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2022 Feb 1; accessed 2022 Jul 5]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hydrophilicity_plot&oldid=1069216189.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. Peripheral membrane protein. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2022 Apr 27; accessed 2022 Jun 18]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Peripheral_membrane_protein&oldid=1085014704.

Zedalis J, Eggebrecht J. 2018. Biology for AP® courses. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. The cell, Chapter 5, Science practice challenge questions. https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/5-science-practice-challenge-questions.

a phospholipid bilayer with embedded (integral) or attached (peripheral) proteins that separates the internal contents of the cell from its surrounding environment

combination of carbohydrates and lipids

amphipathic lipid made of glycerol, two fatty acid tails, and a phosphate group

a biological membrane involving two layers of phospholipids with their tails pointing inward

molecule possessing a polar or charged area and a nonpolar or uncharged area capable of interacting with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments

fat molecule; consists of three fatty acids linked to a glycerol molecule

long-chain of hydrocarbon with single covalent bonds in the carbon chain; the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon skeleton is maximized

long-chain hydrocarbon that has one or more double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain

molecule that does not have the ability to bond with water; “water-fearing”

molecule with the ability to bond with water; “water-loving”

specialized structure that surrounds the cell and its internal environment; controls movement of substances into/out of cell

describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, glycoproteins, and glycolipids (sugar chains attached to proteins or lipids, respectively), resulting in a fluid character (fluidity)

a type of biological membrane that will allow certain molecules or ions to pass through it by diffusion and occasionally by specialized facilitated diffusion

protein integrated into the membrane structure that interacts extensively with the hydrocarbon chains of membrane lipids and often spans the membrane; these proteins can be removed only by the disruption of the membrane by detergents

protein found at the surface of a plasma membrane either on its exterior or interior side; these proteins can be removed (washed off of the membrane) by a high-salt wash

combination of carbohydrates and proteins

an experimental procedure to determine the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal. The crystalline structure causes a beam of X-rays to diffract into many different directions. The angles of the diffracted beams are measured to produce a 3-dimensional image

coating of sugar molecules that surrounds the cell membrane