2.3 Movement of Substances across Membranes — Active Transport

Introduction

In some instances, cells must move materials against a concentration gradient; when this occurs, the cells require an energy source. This process is known as active transport. Active transport involves integral membrane proteins that move substances against their concentration gradient with the use of energy.

A good definition of active transport is that at least one molecule is moved against a concentration gradient. A common energy source is ATP, but other energy sources can also be employed. For example, a sodium-glucose transporter uses a sodium gradient as an energy source for actively transporting glucose into a cell. Additionally, the prokaryotic protein bacteriorhodopsin utilizes light energy to actively pump protons across cell membranes. Thus, it is essential to know that not all active transport uses ATP energy.

In addition to moving small ions and molecules through the membrane, cells also need to remove and take in larger molecules and particles. Some cells are even capable of engulfing entire unicellular microorganisms. You might have correctly hypothesized that the uptake and release of large particles by the cell requires energy. A large particle, however, cannot pass through the membrane via integral proteins, even with energy supplied by the cell. Specialized mechanisms of endocytosis are needed.

Unit 2, Topic 3 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 2, Topic 3, you will be able to:

- Describe how electrochemical gradients affect ion transport.

- Distinguish between primary active transport and secondary active transport.

- Summarize the function of the three major ABC transporter categories: prokaryotes, gram-negative bacteria, and the ABC protein subgroup.

- Compare the function and significance of three examples of membrane transport in organisms.

- Compare two mechanisms by which glucose can be transported into cells.

- Compare the substrate-binding affinities and expression of five types of glucose transporters.

- Describe and draw the mechanism of insulin-dependent glucose transport and its relevance to type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the relevance of insulin-dependent and -independent glucose transport in finding a cure for diabetes in a global context.

- Describe the differences and similarities between endocytosis, including phagocytosis, pinocytosis, exocytosis, and receptor-mediated endocytosis.

| Unit 2, Topic 3—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 2, Topic 3 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Active transport. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: ABC transporters. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Primary and secondary active transport. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Glucose transporters. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Transporters in the gut. | 35 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane transport in diabetes. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Insulin and the global perspective. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Phagocytosis. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Receptor-mediated endocytosis. | 5 |

| Attempt self-check questions—7 in total. | 15 |

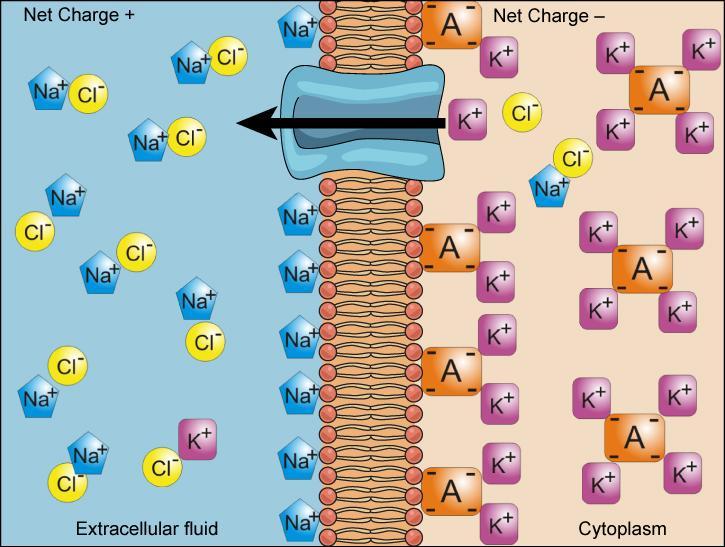

Electrochemical Gradient

The previous chapter discussed simple concentration gradients — differential concentrations of a substance across a space or a membrane — in living systems, but gradients are more complex than that. Because cells contain proteins (mostly negatively charged) and because ions move into and out of cells, there is an electrical gradient (a difference of charge) across the plasma membrane. The interior of living cells is electrically negative with respect to the extracellular fluid in which they are bathed; at the same time, cells have higher concentrations of potassium (K+) and lower concentrations of sodium (Na+) than the extracellular fluid. Therefore, the interior of living cells is electrically negative in comparison to the extracellular fluid due to ion concentration variations on either side of the membrane; this difference in charge/voltage across the plasma membrane is called the membrane potential. The membrane potential of a typical cell is -40 to -80 millivolts, with the minus sign meaning that the inside of the cell is more negative than the outside.

As an example of how the membrane potential can affect ion movement, look at sodium and potassium ions in a living cell. In general, the inside of a cell has a higher concentration of K+ and a lower concentration of Na+ than the extracellular fluid around it (Figure 1).

- Sodium ions outside of a cell tend to move into the cell based on their concentration gradient (the lower concentration of Na+) and the voltage across the membrane (the more negative charge inside the membrane).

- Because K+ is positive, the voltage across the membrane encourages its movement into the cell; however, its concentration gradient will tend to drive it out of the cell (towards the region of lower concentration). The final potassium concentrations on both sides of the membrane will be a balance between these opposing forces.

The combination of concentration gradient and voltage affecting an ion’s movement is called the electrochemical gradient, and it is especially important to muscle and nerve cells.

Self-Check

Injecting a potassium solution into a person’s blood is lethal. This method is how capital punishment and euthanasia subjects die. Why do you think a potassium solution injection is lethal?

Show/Hide answer.

Potassium dissipates the electrochemical gradient in cardiac muscle cells, preventing them from contracting. Cells typically have a high potassium concentration in the cytoplasm and are bathed in a high sodium concentration. The potassium injection dissipates this electrochemical gradient. In heart muscle, the sodium/potassium potential transmits the signal that causes the muscle to contract. When this potential dissipates, the signal cannot be transmitted, and the heart stops beating. Potassium injections are also used to stop the heart from beating during surgery.

Active Transport: Moving Against a Gradient

Cells require energy to move substances against a concentration or electrochemical gradient. This energy comes in the form of ATP generated through cellular metabolism. Active transport mechanisms, collectively called pumps or carrier proteins, work against electrochemical gradients. With the exception of ions, small nonpolar substances constantly pass through plasma membranes. Active transport maintains ion and other substance concentrations needed by living cells to deal with these passive changes. A cell may spend much of its metabolic energy maintaining these processes. Because active transport mechanisms depend on cellular metabolism for energy, they are sensitive to many metabolic poisons that interfere with the supply of ATP.

Two mechanisms exist for the transport of small-molecular weight material and macromolecules.

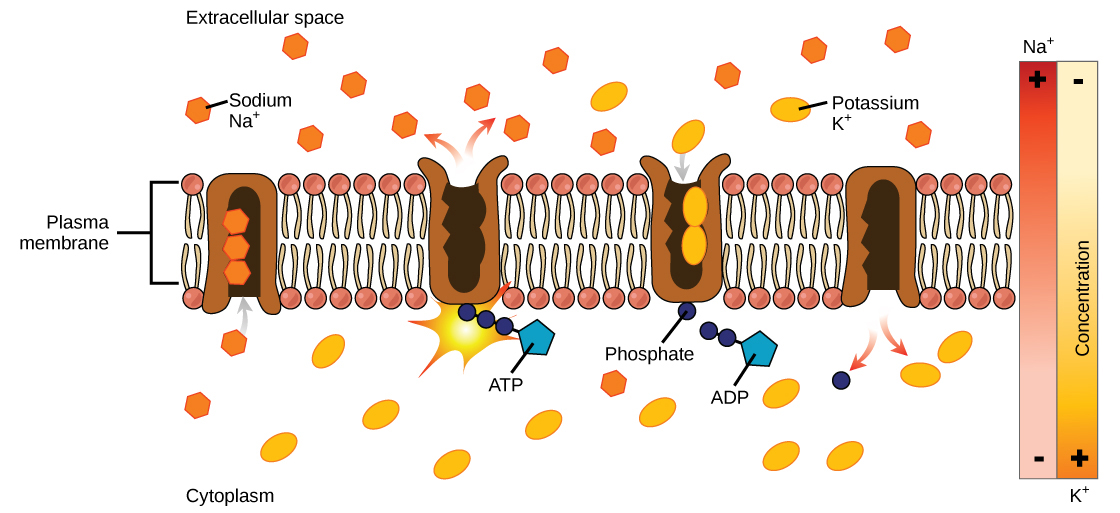

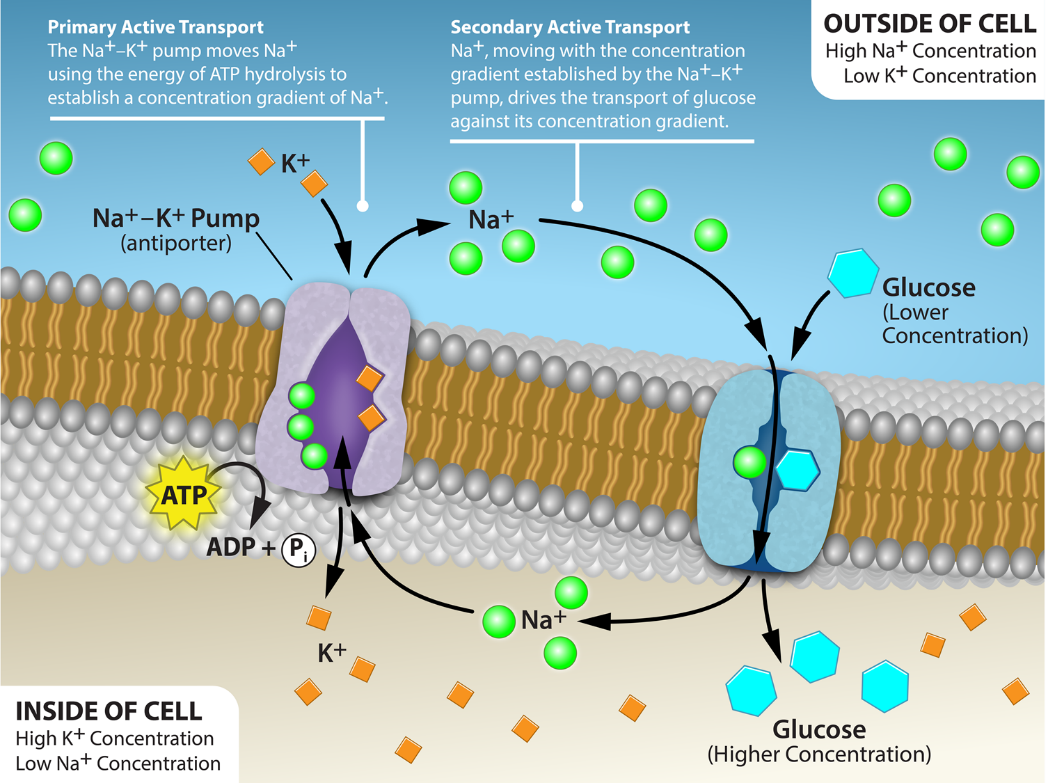

- Primary active transport moves ions across a membrane and creates a difference in charge across that membrane. The primary active transport system uses ATP to move a substance, such as an ion, into the cell, and often at the same time, a second substance moves out of the cell. The sodium-potassium pump, an important pump in animal cells, expends energy to move potassium ions into the cell and a different number of sodium ions out of the cell. The action of this pump results in a concentration and charge difference across the membrane.

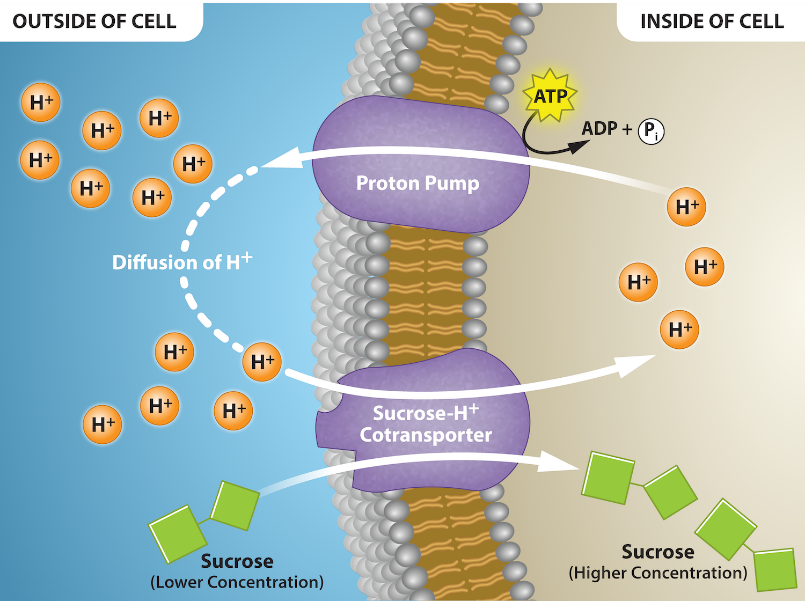

- Secondary active transport describes the movement of material using the energy of the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport. Using the energy of the electrochemical gradient created by the primary active transport system, other substances, such as amino acids and sugars (Figure 2), can be brought into the cell through membrane channels. ATP itself is formed through secondary active transport using a hydrogen ion gradient in the mitochondrion.

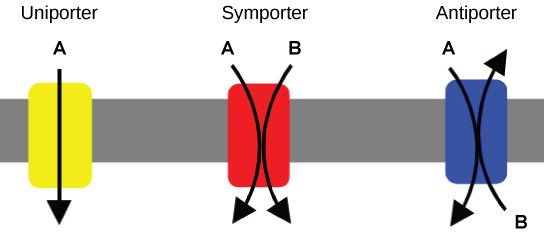

Carrier Proteins for Active Transport

An important membrane adaptation for active transport is having specific carrier proteins or pumps to facilitate movement. As discussed in Unit 2, Topic 2, there are three protein transporter types (Figure 3). A uniporter carries one specific ion or molecule. A symporter carries two different ions or molecules both in the same direction. An antiporter also carries two different ions or molecules but in different directions. All three transporters can also transport small, uncharged organic molecules (e.g., glucose) and facilitate diffusion, but they do not require ATP to work in the latter process. Some examples of pumps for active transport are Na+/K+ ATPase, which carries sodium and potassium ions, and H+-K+ ATPase, which carries hydrogen and potassium ions. Both pumps are antiporter carrier proteins. Two other carrier proteins are Ca2+ ATPase and H+ ATPase, which carry only calcium and only hydrogen ions, respectively. Both are pumps.

Sodium Potassium Pump (Na+/K+ ATPase)

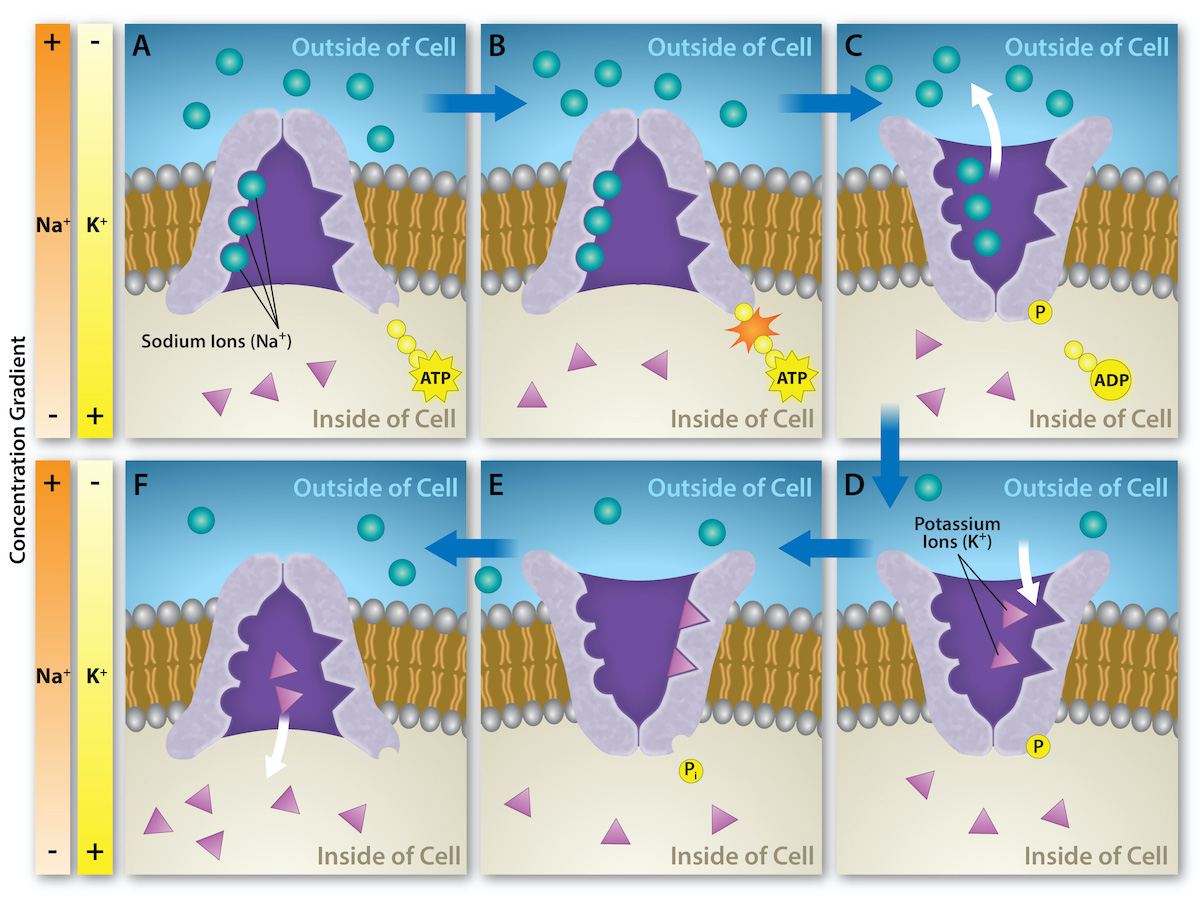

The Na+/K+ ATPase antiporter (Na+/K+ pump) (Figure 4 and Figure 5) is an essential, integral membrane transport protein that moves three sodium ions out of the cell and two potassium ions into the cell with each cycle of action. In each case, the ions move against their concentration gradients. Additionally, the movement of three positive charges out of the cell and only two positive charges in causes a membrane potential, which is vital in establishing homeostasis within cells.

The Na+/K+ pump uses the energy of ATP to create and maintain ion gradients; these gradients are important for maintaining cellular osmotic pressure and (in nerve cells) creating the sodium and potassium gradients necessary for signal transmission. If the system fails to function, the cell swells due to the movement of water into the cell through osmotic pressure. The transporter expends about one-third of the ATP energy of animal cells. The cycle of the action occurs as follows (Figure 5):

- The pump opens towards the inside of the cell. In this form, the pump really likes to bind to (has a high affinity for) sodium ions and takes up three of them.

- When the sodium ions bind, they trigger the pump to hydrolyze (break down) ATP. One phosphate group from ATP attaches to the pump, which is then said to be phosphorylated. ADP is released as a by-product.

- Phosphorylation makes the pump change shape, re-orienting itself to open towards the extracellular space. In this conformation, the pump no longer likes to bind to sodium ions (has a low affinity for them), so it releases the three sodium ions outside the cell.

- In its outward-facing form, the pump switches allegiances and now really likes to bind to (has a high affinity for) potassium ions. It binds two of them, triggering the removal of the phosphate group attached to the pump in step 2.

- With the phosphate group gone, the pump changes back to its original form, opening towards the interior of the cell.

- In its inward-facing shape, the pump no longer likes to bind to (has a low affinity for) potassium ions, so it releases the two potassium ions into the cytoplasm. The pump is now back to where it was in step 1, and the cycle can begin again.

This cycle may seem complicated, but it just involves the protein going back and forth between two forms: an inward-facing form with high affinity for sodium (and low affinity for potassium) and an outward-facing form with high affinity for potassium (and low affinity for sodium). The protein can be toggled back and forth between these forms by adding or removing a phosphate group, which is, in turn, controlled by the binding of the ions that need transporting.

Several things have happened because of this process. At this point, there are more sodium ions outside the cell than inside and more potassium ions inside than out. For every three sodium ions that move out, two potassium ions move in. This results in the interior being slightly more negative relative to the exterior. This difference in charge is important for creating the necessary conditions for the secondary process. The sodium-potassium pump is, therefore, an electrogenic pump (a pump that creates a charge imbalance), creating an electrical imbalance across the membrane and contributing to the membrane potential.

Self-Check

Explain whether you think the sodium-potassium pump is an enzyme.

Show/Hide answer.

There are two clues to answer this question. First, most enzyme names end in ‘ase.’ Second, ATPases are a group of enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of a phosphate bond in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to form adenosine diphosphate (ADP). They harness the energy released from the breakdown of the phosphate bond and utilize it to perform other cellular reactions.

Learning Activity: Active Transport

This activity reviews primary active transport, using the sodium-potassium pump as an example.

- Watch the video “The Sodium-Potassium Pump” (2:26 min) by RicochetScience (2016), which describes the sodium-potassium pump. Make notes and keep a copy for study purposes.

- Draw your own membrane and the entire cycle that moves sodium and potassium ions across a membrane.

- Answer the following questions:

- Explain why the binding of inorganic phosphate changes the shape of the pump.

- What causes the sodium ions to be released?

- Why does potassium binding cause a shape change?

- Explain how an electrochemical gradient is established across the plasma membrane.

Calcium Pumps

Unlike Na+ or K+, the Ca2+ gradient is not very important for the electrochemical membrane potential or the use of its energy. However, calcium ions are necessary for muscular contraction and play an important role in signalling within cells. Therefore, cytosolic calcium concentrations are kept low to avoid the continual activation of these processes. Both primary and secondary active transport mechanisms affect intracellular calcium ion concentrations.

Calcium ATPase pumps are a family of uniport ion transporters found in plasma membranes and in the terminal cisternae of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in all animal cells. Calcium ATPases in the plasma membrane are responsible for the primary active transport of two Ca2+ out of the cell to maintain the steep Ca2+ electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane. As a result, intracellular calcium ion concentrations are roughly 10,000 times lower than extracellular concentrations. The sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle cells has calcium ATPases continually transporting calcium ions from the sarcoplasm into the lumen. In addition, mitochondria contribute to the low cytosolic calcium concentrations by using calcium ATPases to pump calcium into the mitochondrial matrix from the cytosol.

The sodium-calcium exchanger is an electrogenic antiport pump that uses sodium’s movement into the cell as a driving force to move calcium out of the cell; however, its direction can reverse in some circumstances. This pump is a high-capacity system that quickly moves a lot of calcium, moving up to 5,000 calcium ions per second; many tissues with many functions use this pump.

One important function of the Na+/Ca2+ pump occurs in heart cells, where calcium plays an important role in heart muscle contractions. Calcium efflux from the cells is the normal operation of the pump; however, during the upstroke of the cycle, a large amount of sodium ions moves into the heart cell. When this occurs, the pump reverses and briefly pumps Na+ out and Ca2+ in.

Since calcium helps stimulate cardiac muscle contraction, this movement can help the heart beat stronger. It is the focus of how digitalis can treat congestive heart failure. Digitalis blocks the sodium-potassium ATPase, which interferes with the sodium ion gradient. As noted above, calcium pumps into the cell when the Na+ gradient orients in the wrong direction. Therefore, digitalis can treat congestive heart failure because it increases the calcium concentration in the heart cells, resulting in more forceful beats.

ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters (ABC Transporters)

ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporters) are members of one of the largest and most ancient protein superfamily; this family has representatives in all extant phyla, from prokaryotes to humans. ABC transporters are transmembrane proteins that utilize ATP hydrolysis energy to carry out certain biological processes, including translocation of various substrates across membranes and non-transport-related processes (e.g., translation of RNA and DNA repair). They transport a wide variety of substrates across extra- and intracellular membranes, including metabolic products (e.g., lipids and sterols) and drugs. Proteins are classified as ABC transporters based on the sequence and organization of their ATP-binding cassette (ABC) domain(s).

ABC transporters are involved in tumour resistance, cystic fibrosis, and many other inherited human diseases; they also play a role in how both bacterial (prokaryotic) and eukaryotic (including human) develop resistance to multiple drugs. Bacterial ABC transporters are also essential in cell viability, virulence, and pathogenicity.

ABC transporters are divided into three main functional categories. In prokaryotes, importers mediate the nutrient uptake in a cell. These importers can transport specific substrates, including ions, amino acids, peptides, sugars, and other mostly hydrophilic molecules. The membrane-spanning region of the ABC transporter protects hydrophilic substrates from the membrane bilayer lipids, providing them a pathway across the cell membrane. In gram-negative bacteria, exporters transport lipids and some polysaccharides from the cytoplasm to the periplasm. Eukaryotes do not possess any importers. Exporters (or effluxers), which are present in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, function as pumps that extrude toxins and drugs out of the cell. The third subgroup of ABC proteins does not function as transporters; instead, they are involved in translation and DNA repair processes.

In bacterial efflux systems, certain substances that need to extrude from the cell include bacterial cell surface components (e.g., capsular polysaccharides, lipopolysaccharides, and teichoic acid), proteins involved in bacterial pathogenesis (e.g., hemolysis, heme-binding protein, and alkaline protease), heme, hydrolytic enzymes, S-layer proteins, competence factors, toxins, antibiotics, bacteriocins, peptide antibiotics, drugs, and siderophores. They also play an important role in biosynthetic pathways, including extracellular polysaccharide biosynthesis and cytochrome biogenesis.

Prokaryotic ABC exporters are abundant and have close homologues in eukaryotes. These transporters are classified based on the type of substrate they transport. One class is involved in protein export (e.g., toxins, hydrolytic enzymes, S-layer proteins, antibiotics, bacteriocins, and competence factors) and the other in drug efflux. ABC transporters have gained extensive attention because they contribute to antibiotic and anticancer agent resistance in cells by pumping drugs out of the cells.

Example of ABC Importer Structure and Transport Mechanism

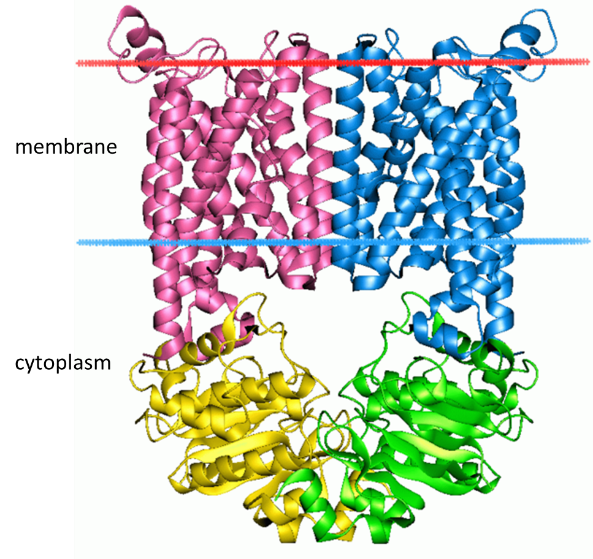

All ABC transporters have two distinct domains: the transmembrane domain (TMD) and the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD). The TMD, also known as the membrane-spanning domain (MSD) or integral membrane (IM) domain, consists of alpha helices embedded in the membrane bilayer (Figure 6). It recognises a variety of substrates and undergoes conformational changes to transport the substrate across the membrane. On the other hand, the NBD, or ATP-binding cassette (ABC) domain, is located in the cytoplasm and has a highly conserved sequence. The NBD is the site for ATP binding. The ATPase subunits utilize the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to provide the energy needed to translocate substrates across membranes, either for uptaking or exporting the substrate.

Self-Check

Identify the secondary structures and their locations in the 3D representation of the Escherichia coli BtuCD ABC transporter (Figure 6). Identify any other protein structure levels shown in this protein image.

Show/Hide answer.

Secondary structures include transmembrane alpha helices, cytoplasmic alpha helices, and cytoplasmic beta sheets (ribbon shapes). Tertiary structure is the whole shape of the protein, and quaternary structure is the four subunits that came together.

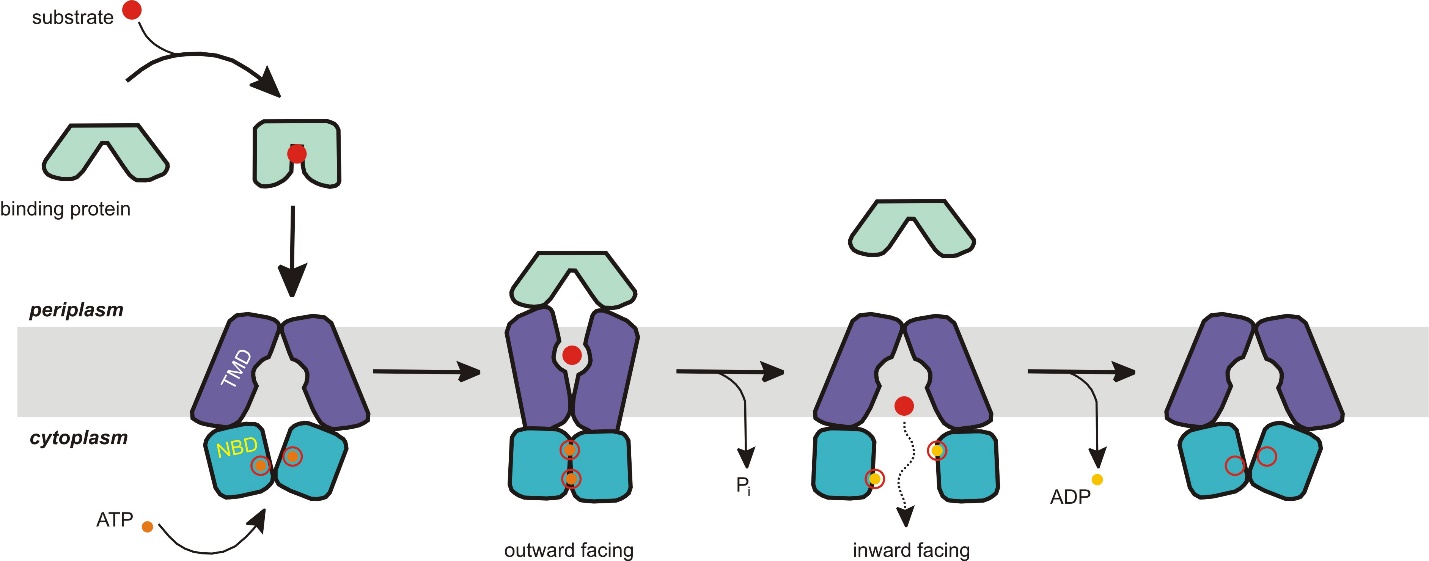

The transport mechanism for importers supports the alternating-access model (Figure 7). Importers have a resting state facing inward where the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) dimer interface is held open by the TMDs; TMDs face outward, but the NBD blocks them from the cytoplasm. When the closed, substrate-loaded binding protein docks towards the periplasmic side of the transmembrane domains, ATP binds, and the NBD dimer closes. The transporter switches its resting state into an outward-facing conformation, where the TMDs have reoriented to receive substrate from the binding protein. After hydrolysis of ATP, the NBD dimer opens, and the TMD releases the substrate into the cytoplasm. The release of ADP and Pi reverts the transporter to its resting state.

The ATP-switch model using this mechanism has only one inconsistency: the conformation in its resting nucleotide-free state does not match the expected outward-facing conformation. Despite this inconsistency, the key point is that the NBD does not dimerize unless ATP and binding protein are bound to the transporter.

In summary, most ABC proteins function as ATP-dependent active transporters that couple ATP binding and hydrolysis to transport substrates against their concentration gradient across the membrane.

Learning Activity: ABC Transporters

This activity provides an overview of ABC transporter structure and functions.

- Watch the video “ABC Transports” (2:00 min) by Ryan Abbott (2017) for a brief overview of ABC transporters.

- Watch the video “ABC Transports” (7:56 min) by Biology Brainery (2020) for a more detailed explanation.

- Answer the following questions and keep notes for study purposes:

- Why are they called ABC transporters?

- Are ABC transporters an example of primary or secondary active transport? Explain.

- Compare the conformational switch mechanism of ABC transporters to that of the sodium-potassium pump.

- Why are ABC transporters very important to human health?

Sodium/Glucose Transporter

A secondary active transport example is the sodium/glucose transporter. ATP hydrolysis, while a common energy source for many biological processes, is not the only energy source for transport. Another possibility involves coupling the active transport of one solute against its gradient with the energy from the passive transport of another solute down its gradient. Figure 8 illustrates the sodium/glucose transporter; this transporter is a symport example where both solutes cross the membrane in the same physical direction. However, one solute travels down its gradient (sodium ions) while the other travels up or against its concentration gradient (glucose). Na+ movement is the driving force behind this transport mechanism. The Na+ gradient across the membrane is an extremely important energy source for most animal cells. However, this is not universal for all cells or even all eukaryotic cells. In most plant cells and unicellular organisms, the H+ (proton) gradient plays the role that Na+ does in animals.

Self-Check

Does primary and secondary active transport require a channel, carrier proteins, or both? Are these proteins the same as those used in facilitated diffusion?

Show/Hide answer.

Active transport uses carrier proteins, not channel proteins. These carrier proteins differ from the ones seen in facilitated diffusion, as they often need ATP (or another energy source) to change conformation. Channel proteins are not used in active transport because substances can only move through them along their concentration gradient.

Learning Activity: Primary and Secondary Active Transport

- Watch the following videos to review different aspects of active transport:

- “Primary vs. secondary active transport” (4:45 min) by GHC Biology (2019).

- “Primary vs. secondary active transport” (3:50 min) by Nonstop Neuron (2021).

- “Cotransport” (1:53 min) by Andrew Vinal (2013).

- Compare the mechanisms of primary and secondary active transport. Note the integral membrane protein types involved. Keep a copy for study purposes.

Glucose Transport in Biological Systems

As previously discussed, nearly all energy used by living cells comes to them through sugar glucose bonds. Glycolysis is the first step in breaking down glucose to extract energy for cellular metabolism. In fact, nearly all living organisms carry out glycolysis during their metabolism. The process does not use oxygen directly and, therefore, is classified as anaerobic. Glycolysis takes place in the cytoplasm of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Glucose can enter heterotrophic cells in the following two ways:

- Secondary active transport is the transport takes place against the glucose concentration gradient (see Figure 8).

- Glucose transporter proteins (GLUT proteins) are the integral protein group assisting in facilitated diffusion of glucose.

GLUTs (GLUcose Transport proteins) are uniport, type III integral membrane proteins that transport glucose across membranes into cells (Table 1). All phyla have GLUTs; humans have an abundance of them with 12 GLUT genes. Each GLUT has a specific function expressed through different tissues. Some transporters have a higher outward substrate-binding site affinity (Km = concentration at which half of the active sites are filled) than at the cytoplasmic binding site; this makes them more useful at bringing glucose into the cell. Note that the lower Km, the higher the affinity. In other words, transporters with a high affinity for glucose readily bind the solute and do not need a high glucose concentration to reach saturation.

Table 1 summarizes the locations and functions of five of the more well-studied GLUTS.

| Table 1: Glucose transporters (GLUTs) found in mammalian cells. (Katzman et al./Fundamentals of Cell Biology) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 |

|||

| Name | Tissue | Km | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | · Blood (erythrocytes) · Blood-brain barrier · Heart (lesser extent) |

1 mM | · Basal glucose uptake · Insulin independent · Low Km / high affinity |

| GLUT2 | · Liver · Pancreatic beta cells · Enterocytes of small intestine (basal side & sometimes luminal side) |

15–20 mM | · Insulin independent · High Km / low affinity · Participates in insulin regulation in the pancreas; removes excess glucose from the blood in the liver |

| GLUT3 | · Brain · Neurons · Sperm |

1 mM | · Basal glucose uptake · Insulin independent · Low Km / high affinity |

| GLUT4 | · Skeletal muscle · Adipose tissue (fat cells) |

5 mM | · Insulin dependent · Moderate Km / moderate affinity |

| GLUT5 | · Enterocytes of small intestinal epithelium (luminal side) | – | · Insulin independent · Fructose transport |

| SGLT1 | · Enterocytes of small intestinal epithelium (luminal side) | 0.5–2 mM (Ghezzi et al., 2018; Koepsell, 2020) | · Insulin independent · Low Km / high affinity · ATP- and Na-dependent · Glucose absorption |

| SGLT2 | · Proximal tubule of nephron (kidney) | 5 mM (Ghezzi et al., 2018) | · Insulin independent · ATP- and Na-dependent · Glucose retention |

Learning Activity: Glucose Transporters

This activity provides more details about glucose transporters and the different types of glucose transporters (e.g., GLUTs). Furthermore, it introduces sodium-dependent glucose transporters (SGLTs).

- Watch “Glucose Transporters (GLUTs and SGLTs)” by JJ Medicine (7:33 min).

- Take notes on where these transporters are found in the body, the type of transport mechanism they mediate, their kinetic properties and their relevance in whole-body metabolism.

Glucose Transporters in the Gut

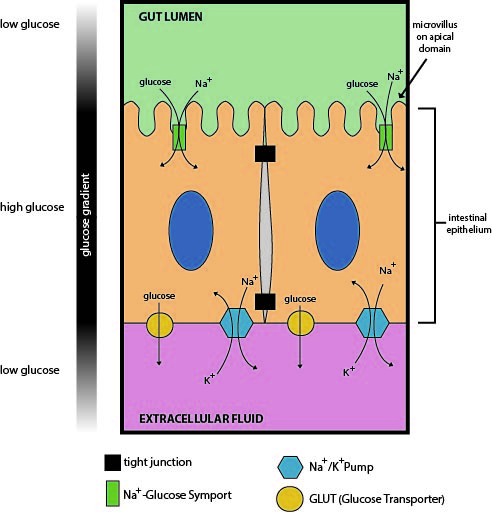

Absorbing nutrients from the digestive system is necessary for animal life. Sodium/glucose transport proteins are symporters that move glucose into cells in the small intestine and nephron of the kidney. The SGLT1 transporter works in the intestinal mucosa cellular membrane to absorb glucose from the gut. Meanwhile, in the kidney, the SGLT2 transporter works in the proximal nephron tubules to promote filtered glucose reabsorption by the proximal kidney tubules.

In the intestinal mucosa, SGLT1 transports glucose out of the gut lumen and into the small intestine cells (enterocytes) (Figure 9). Later, the glucose is exported out the other side of the enterocytes and into the interstitial space; a glucose transporter (GLUT2) in the body uses this glucose in a process called transcytosis. GLUT2 is a uniport protein that facilitates glucose transport by spontaneously opening and closing the transport protein. This results in glucose moving from a high concentration within the enterocytes to a low concentration in the bloodstream. The glucose is then transported to cells in the body to supply fuel for ATP production, driving the metabolic process. The sodium-potassium pump then restores the sodium concentration to homeostasis levels. The lower intracellular sodium levels ensure that luminal sodium flows down its concentration gradient to cotransport glucose through SGLT1. SGLT1 transports one glucose molecule into the cell for every two sodium ions transported into the cell.1

Learning Activity: Transporters in the Gut

This activity will compare the transport directionality types and their cooperative use in intestinal epithelial cells. Maintaining cellular homeostasis requires many transport systems to work together.

This activity includes a synthesis exercise to test your knowledge of the previously mentioned transport systems and a video series illustrating how three membrane transport mechanism types cooperate to move glucose from our digestive system into our cells.

- Watch the following videos:

- “Types of Transport – Uniport, Antiport and Symport” (2:09 min) by Homework Clinic (2020). Make notes on the two types of active transporters involved.

- “Carbohydrate (Glucose) Absorption” (7:17 min) by Wondersofchemistry (2018). Please note the labelling error at 3 minutes, 40 seconds. The enterocyte apical (lumen side) and basolateral (bloodstream side) sides should be reversed. These parts are labelled correctly in the diagram below.

- Review the description in “Uniporters, symporters and antiporters | Biology | Khan Academy” (7:12 min) by Khan Academy (2015).

- Complete the following interactive exercise to test your knowledge of glucose cotransport in the gut.

- Answer the following questions:

- Describe how these transport systems work together to maintain glucose homeostasis. Use proper terminology when discussing the various transporters and their locations within enterocytes.

- What drives the continuous glucose uptake from the gut lumen and the glucose transport across the cell and into the blood, even when the glucose concentration in the lumen falls below that in the epithelial cell cytoplasm? How does this relate to the Km of SGLT1? What aspect of the intestinal brush border may help with glucose absorption and metabolic processes? (integrate with Unit 1, Topic 2). What is the name of the process in which a molecule is moved into, across and out the other side of a cell?

- There is a tight junction separating the two enterocytes in Figure 9. Explain why the restriction to membrane protein mobility caused by this tight junction is important for glucose absorption (integrate with Unit 2, Topic 1). What would happen in the absence of this tight junction? Use proper terminology and cite specific and relevant transporters.

Insulin-Dependent Regulation of Glucose Levels

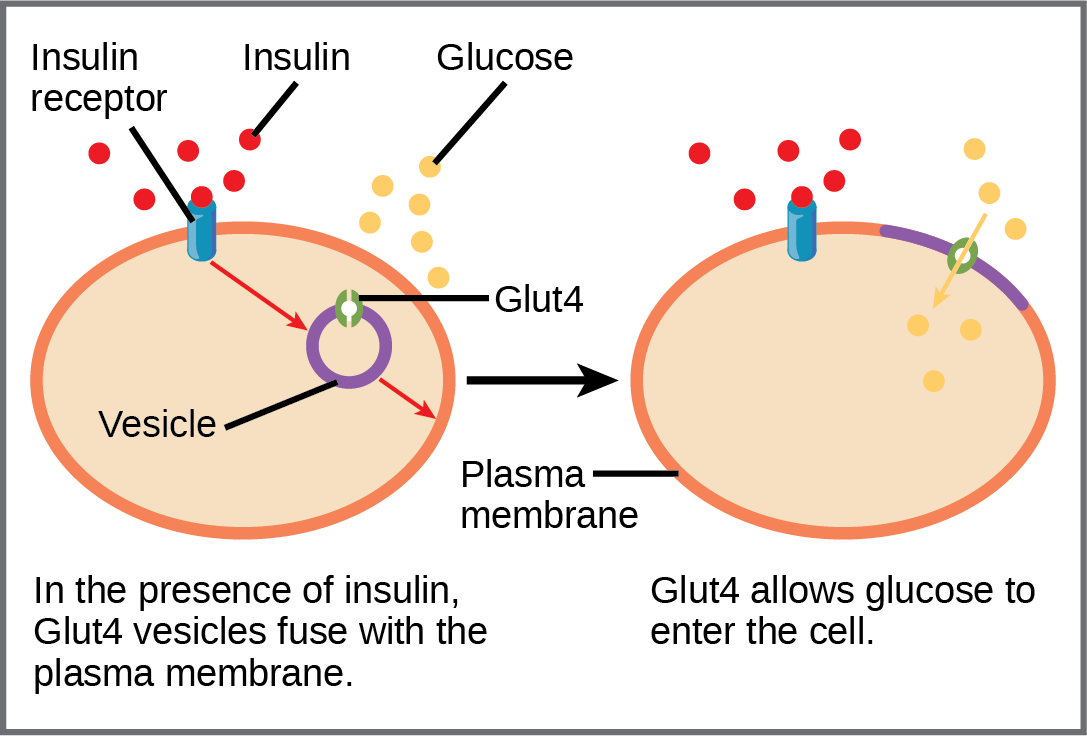

Regulated by insulin, the GLUT4 transporter is found primarily in adipose and striated muscle tissue (see Table 1). It has 12 transmembrane domains. Insulin alters intracellular trafficking pathways in response to increases in blood sugar. This change results in the cell favouring moving various GLUT proteins (including GLUT4) from intracellular vesicles to the cell membrane, thus stimulating the uptake of glucose (Figure 10).

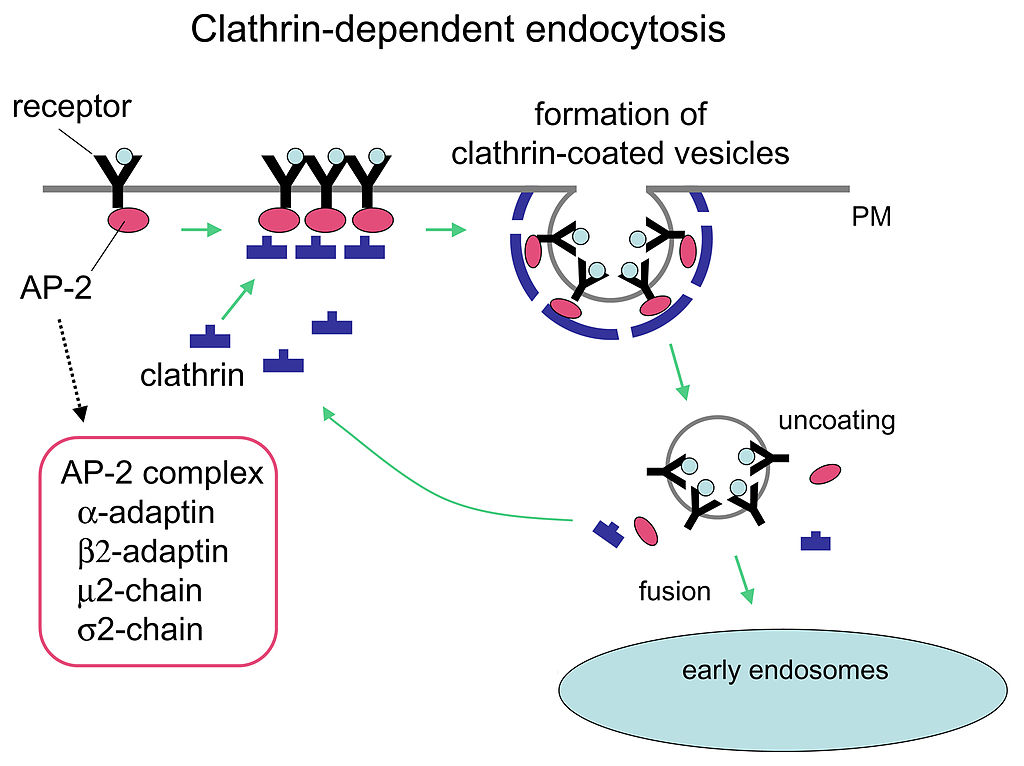

Cells in the body require nutrients to function; they obtain these nutrients through feeding. The body uses hormones to moderate energy stores, which includes managing nutrient intake, storing excess intake, and utilizing reserves (when necessary). Beta cells in the pancreas produce insulin; rising blood glucose levels (e.g., after consuming a meal) stimulate these cells to release insulin. Insulin lowers blood glucose levels by enhancing the glucose uptake rate and utilization by target cells, which use glucose for ATP production. It also stimulates the liver to convert glucose to glycogen, which cells store for later use. Insulin also increases glucose transport into certain cells, such as muscle cells and the liver. This results from an insulin-mediated increase in the number of glucose transporter proteins in cell membranes, which remove glucose from circulation by facilitated diffusion. As insulin binds to its target cell via insulin receptors and signal transduction (see Unit 4), it triggers the cell to incorporate the GLUT4 glucose transport proteins into its membrane. This action allows glucose to enter the cell, which can use the glucose as an energy source. After insulin stimulation ends, endocytosis brings GLUT4 back into the cell through vesicle budding on the plasma membrane containing clathrin. Upon internalization, GLUT4 becomes a part of early endosomes and is re-sorted back into intracellular vesicles.

However, this process does not occur in all cells: some cells, including those in the kidneys and brain, can access glucose without using insulin. Insulin also stimulates glucose conversion into fat in adipocytes and protein synthesis. These actions mediated by insulin cause blood glucose concentrations to fall called a hypoglycemic “low sugar” effect, which inhibits further insulin release from beta cells through a negative feedback loop.

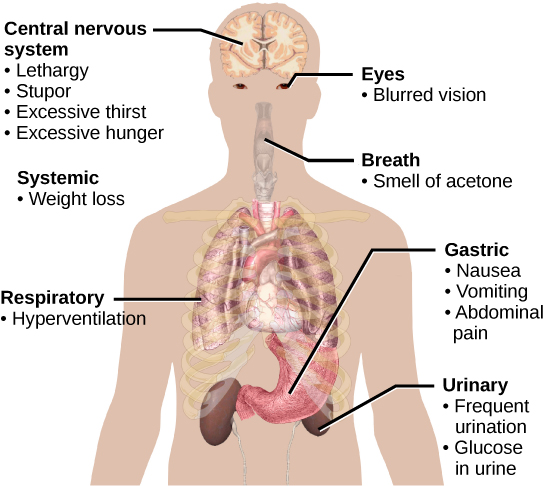

Impaired insulin function can lead to a condition called diabetes mellitus. Figure 11 illustrates the main symptoms of this condition. Diabetes mellitus can be caused by low levels of insulin production by the beta cells in the pancreas (Type 1 diabetes) or by reduced sensitivity of tissue cells to insulin (Type 2 diabetes). Both diabetes types prevent glucose from being absorbed by cells, causing high blood glucose levels, known as hyperglycemia (high sugar). High blood glucose levels make it difficult for the kidneys to recover all the glucose from nascent urine, resulting in the loss of glucose in urine. High glucose levels also result in the kidneys reabsorbing less water, causing them to produce high amounts of urine; this may result in dehydration. Over time, high blood glucose levels can cause nerve damage to the eyes and peripheral body tissues and damage to the kidneys and cardiovascular system. Too much insulin secretion can cause hypoglycemia (low blood glucose levels), causing insufficient glucose availability to cells. This condition often leads to muscle weakness and can sometimes result in unconsciousness or death if left untreated.

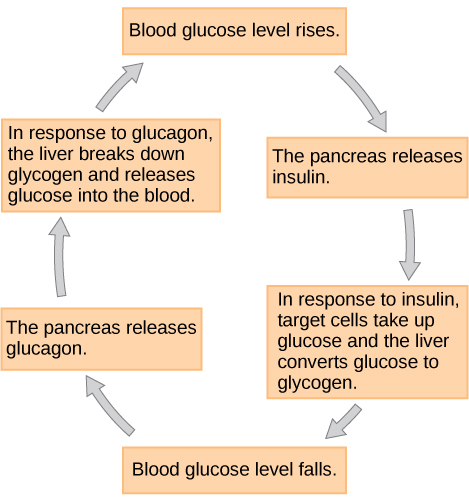

When blood glucose levels decline below normal levels, such as between meals or when the body rapidly utilizes glucose during exercise, alpha cells in the pancreas release the hormone glucagon. Glucagon raises blood glucose levels, eliciting what is called a hyperglycemic effect, by stimulating skeletal muscle cells and liver cells to break down glycogen into glucose in a process called glycogenolysis. Glucose can then be utilized as energy by muscle cells and released into circulation by the liver cells. Glucagon also stimulates the liver to absorb amino acids from the blood, which the liver converts to glucose. This glucose synthesis process is called gluconeogenesis. Glucagon also stimulates adipose cells to release fatty acids into the blood. These actions mediated by glucagon increase blood glucose levels to normal homeostatic levels. Rising blood glucose levels inhibit further glucagon release by the pancreas via a negative feedback mechanism. In this way, insulin and glucagon work together to maintain homeostatic glucose levels, as shown in Figure 12.

Self-Check

Pancreatic tumours may cause excess secretion of glucagon. Type I diabetes results from the failure of the pancreas to produce insulin. Which of the following statements about these two conditions is true?

- A pancreatic tumour and type I diabetes will have the opposite effects on blood sugar levels.

- A pancreatic tumour and type I diabetes will both cause hyperglycemia.

- A pancreatic tumour and type I diabetes will both cause hypoglycemia.

- Both pancreatic tumours and type I diabetes result in the inability of cells to take up glucose.

Show/Hide answer.

b. A pancreatic tumour and type I diabetes will both cause hyperglycemia.

Learning Activity: Membrane Transport in Diabetes

Watch the following videos and answer the associated questions. Keep your own notes and answers for future study purposes.

- “Glucose insulin and diabetes” (7:23 min) by Khan Academy (2011).

- “Diabetes Type 1 and Type 2, Animation” (3:45 min) by Alila Medical Media (2014).

- “Glucose Transporters” (14:21 min) by Andrey K (2015).

- Explain the difference between Type 1 and Type II diabetes.

- Discuss which glucose transporter is involved in insulin-dependent glucose intake into skeletal muscle and fat cells. Does it have a high, medium or low Km?

- How is this glucose transporter regulated by insulin? How are endocytosis and clathrin involved in this process?

- What is the relationship between low insulin levels and glucose levels in the kidney? What are the physiological consequences?

- “The Discovery of Insulin” (5:44 min) by Nature Video (2021). Nearly 100 years after insulin was first used to treat diabetes, Professor Chantal Mathieu, Professor of Medicine at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, takes us through the history, development and future of this life-saving drug.

- How was life for individuals with diabetes before the discovery of insulin?

- Who were the three individuals involved in initiating the research into a treatment for Type I diabetes? Where was the research carried out?

- When and where was the first individual treated with insulin for diabetes?

- How did researchers try to alter the insulin?

- How did researchers try to ‘grow’ more insulin? How is insulin ‘evolving’? Comment on how model organisms are used to aid in human health.

- Read the comments below this video. What strikes you when you read them?

- What do you think about Professor Chantal Mathieu’s parting comment? “…I hope we can stop researching insulin quite soon…and that we can finally prevent and cure Type 1 diabetes.”

- Provide your opinion(s) about the worldwide availability of insulin:

- Read the article “Insulin Imports Fail to Meet Many Countries’ Needs” by Boston University Global Development Policy Center (2021).

- Explore the 2021 peer-reviewed academic review article “Insulin imports fail to meet many countries’ needs” by Abhishek Sharma and Warren A. Kaplan (2021). Write your own summary of global concerns about insulin availability.

✮Learning Activity: Insulin and the Global Perspective

Frederick Banting declared that “insulin is not a cure for diabetes; it is a treatment” in his 1923 Nobel lecture. The year 2021 marks 100 years since the discovery of insulin, which revolutionized managing patients with type 1 diabetes. The past 100 years have seen seismic shifts in our understanding of the pathogenesis of the different types of diabetes, leading to advances in patient care. This Nature Milestones in Diabetes highlights some of these key discoveries, which lay a path to the elusive goal of finding a cure for diabetes.

- Scroll through Nature‘s “Milestones in Diabetes” interactive timeline by Greenhill et al. (2021) (or download the PDF) and pick out relevant facts related to Unit 2, Topic 3 Learning Objectives:

- Describe how electrochemical gradients affect ion transport.

- Distinguish between primary active transport and secondary active transport.

- Summarize the function of the three major ABC transporter categories: in prokaryotes, gram-negative bacteria and the subgroup of ABC proteins.

- Compare the function and significance of three examples of membrane transport in organisms.

- Compare two mechanisms by which glucose can be transported into cells.

- Compare the substrate-binding affinities and expression of five types of glucose transporters.

- Describe and draw the mechanism of insulin-dependent glucose transport and its relevance to type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the relevance of insulin-dependent and independent glucose transport in finding a cure for diabetes in a global context.

- Describe the differences and similarities between endocytosis, including phagocytosis, pinocytosis, exocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis.

- Which discoveries in the milestone relate to the Unit 2, Topic 3 learning objectives?

- Describe the biological tools researchers used in 1988 to identify tissues and cells expressing important insulin-stimulated glucose transporters. How do these tools relate to information discussed in Unit 1, Topic 3? What did they name the newly discovered glucose transporter?

- Go to the LabXchange website and view the different tabs in the “Diabetes Prevalence” interactive activity by Our World in Data (2021). Click on ‘Start interactive’ to view a bar graph of the prevalence of type 1 or type 2 diabetes in certain countries. Click on ‘MAP’ at the bottom of the screen to view the worldwide prevalence. Scroll over the percentages to view the countries with the highest and lowest prevalence. Scroll over each country on the map to view whether the prevalence has increased or decreased since 2011.

- Which two countries have the highest prevalence?

- What parts of the world have the lowest prevalence?

- What is the prevalence in Canada vs. the USA?

- Which countries are showing the highest increase in prevalence?

- Go to the LabXchange website and watch “Diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa” by Nature Video (2022).

- Why have people been dying from either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa even though insulin was discovered in 1922?

- Why does Jean Claude Mbanya believe that there is a steep rise in type 2 diabetes prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa? What is the outcome for patients with type 1 diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa? How do these problems compare to patients who have an infectious disease such as AIDS?

- What does Jean Claude Mbanya believe about accessibility to insulin?

- Learn about the process of making more insulin.

- Go to the LabXchange website and watch the short article “Diabetes Types 1 and 2” by Amgen Biotech Experience (2019). Insulin used to be isolated from pig and cow pancreases. How is most insulin made these days?

- Read about how genetically engineered insulin is manufactured in “Producing Human Therapeutic Proteins in Bacteria” by Amgen Biotech Experience (2019) and view the image “Making a Human Therapeutic Protein in Bacteria” also by Amgen Biotech Experience. Describe this process in your own words.

- Read the article “New miniature organ to understand human pancreas development” by Dr. Anne Grapin-Botton and Katrin Boes (2021) to learn about developing miniature human pancreases. Complete the following:

- Describe a pancreatic organoid.

- How does the development of pancreatic organoids relate to topics you learned about in Unit 1?

- How do you think pancreatic organoids may be of use to help cure diabetes?

Endocytosis

Many functions and factors relating to cell membranes do not fit into broad categories. Those items will be the focus of this section.

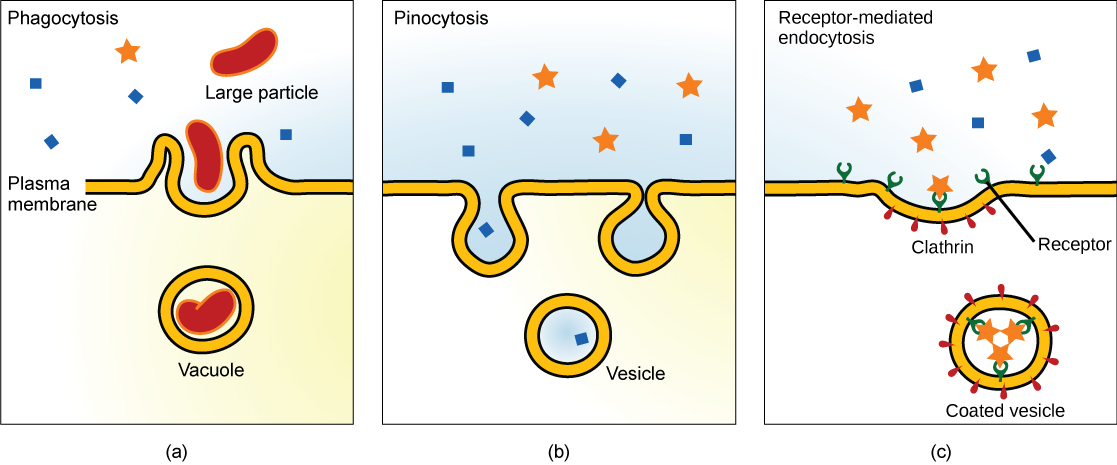

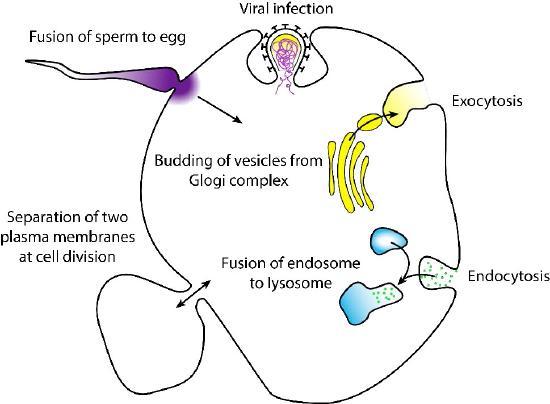

Besides transporter proteins and ion channels, another common way for materials to get into cells is through a process called endocytosis. Endocytosis is a type of active transport that moves particles, such as large molecules, parts of cells, and even whole cells, into a cell. Endocytosis comes in different forms, but all share a common characteristic: the plasma membrane of the cell invaginates, forming a pocket around the target particle. The pocket pinches off, containing the particle in a newly created vacuole formed from the plasma membrane (Figure 13).

Some of these processes, such as phagocytosis, can import much larger particles than would be possible via a transporter protein. As a result, the process usually involves importing many different molecules each time it occurs. The list of compounds entering cells in this way includes low-density lipoproteins and their lipid contents, but it also has things like iron (packaged in transferrin), vitamins, hormones, proteins, and even some viruses sneak in by this means. There are three types of endocytosis we will consider (Figure 13).

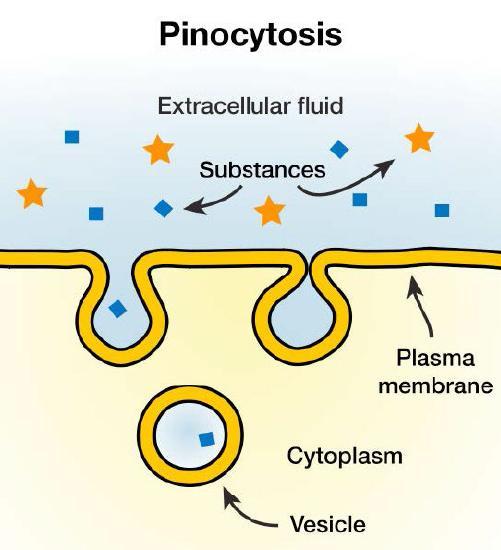

Pinocytosis

A phenomenon known as “cell drinking,” pinocytosis literally involves a cell “taking a gulp” of the extracellular fluid. It does this, as shown in Figure 14, by a simple invagination of the plasma membrane. A pocket results, which pinches off internally to create a vesicle containing extracellular fluid and dissolved molecules. Within the cytosol, this internalized vesicle will fuse with endosomes and lysosomes. The process is non-specific for materials internalized. Therefore, pinocytosis is when the cell engulfs already dissolved or broken-down food.

Pinocytosis is variably subdivided into categories depending on molecular mechanism and what happens to internalized molecules. Pinocytosis is further divided into macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, or clathrin- and caveolin-independent endocytosis. These categories differ in their mechanism for forming the vesicle and the resulting vesicle size. In humans, this process occurs primarily to absorb fat droplets.

A pinocytosis variation is called potocytosis. This process uses a coating protein, called caveolin, on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane; this protein performs a similar function to clathrin. In addition to caveolin, the cavities in the plasma membrane that form the vacuoles have membrane receptors and lipid rafts. The vacuoles or vesicles formed in caveolae (singular caveola) are smaller than those in pinocytosis. Potocytosis either brings small molecules into the cell or transports these molecules through the cell for their release on the other side of the cell. This process is called transcytosis.

One of the best pinocytosis examples is how small intestine cells use their microvilli to absorb extracellular fluid and dissolved solutes. Based on microscopic studies, these cells continually take in fluids through vesicles that constantly pinch off as the cells internalize materials.

Pinocytosis in the kidney ducts contributes to urine formation. By taking in extracellular fluid along with dissolved nutrients through pinocytosis, duct cells separate important nutrients and fluids from urine, which the body expels. This separation ensures that the body retains important materials while removing waste material.

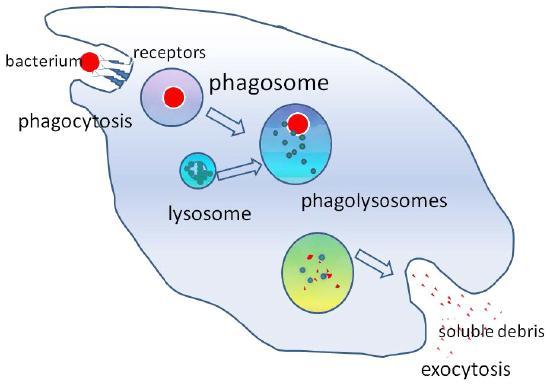

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis (the condition of “cell eating”) is the process by which large particles, such as cells or relatively large particles (0.75 µm in diameter), are internalized by a cell. Cells in the immune system (e.g., neutrophils and macrophages) use phagocytosis to internalize cell debris, apoptotic cells, and microorganisms (Figure 15).

In preparation for phagocytosis, a portion of the inward-facing surface of the plasma membrane becomes coated with a protein called clathrin, which stabilizes this section of the membrane. This coated protein then extends from the cell body and surrounds the particle, eventually enclosing it. Once the cell encloses the vesicle containing the particle, the clathrin disengages from the membrane and the vesicle merges with a lysosome to break down the material in the newly formed compartment (endosome), known as a phagolysosome (Figure 15). The phagolysosome subjects the engulfed particle to toxic conditions to kill it (if it is a cell) and/or to digest it into smaller pieces. Once the lysosome extracts the accessible nutrients from degrading the vesicular contents, the newly formed endosome merges with the plasma membrane and releases its contents into the extracellular fluid. In some cases, the phagocytosing cell may release soluble debris. The endosomal membrane again becomes part of the plasma membrane.

Learning Activity: Phagocytosis

- Scroll through the “Macrophages and Phagocytosis” interactive simulation by LabXchange (2021).

- Describe and draw the process of phagocytosis and how macrophages signal the presence of bacterial invaders to the immune system.

Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

In some instances, endocytosis is a specific mechanism to take up molecules that the cell needs to function. The molecule/ligand can bind to a specific receptor on the cell’s surface that triggers a vesicle to form; this vesicle imports the molecule into the cell. This process is called receptor-mediated endocytosis. In receptor-mediated endocytosis (as in phagocytosis), clathrin attaches to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane (Figure 16).

Cells in a human can take up the cholesterol form known as LDL (low-density lipoprotein or ‘bad cholesterol’) through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Blood continuously transports cholesterol between the liver and all the other tissues. Most of this cholesterol travels as low-density lipoproteins (LDLs). Each LDL particle is a sphere filled with ~1,500 cholesterol molecules, complexed with fatty acids, and coated with a phospholipid layer and a single protein molecule called apolipoprotein B (apoB). Cells that need cholesterol trap and ingest LDLs by receptor-mediated endocytosis, where the LDL binds to specific LDL receptors on the cell’s surface. The cell internalizes LDL into a vesicle, called an endosome, and the LDL receptors are recycled back to the cell’s surface. The endosome then fuses with the lysosome, which breaks down the LDL into monomers needed for cell function.

Although receptor-mediated endocytosis is intended to bring useful substances into the cell, other, less friendly particles may gain entry via the same route. Flu viruses, diphtheria, and cholera toxin all use receptor-mediated endocytosis pathways to gain entry into cells.

Self-Check

Suppose a certain type of molecule had to be removed from the blood by receptor-mediated endocytosis. What would happen if the receptor protein for that molecule were missing or defective?

Show/Hide answer.

If passing the target material (e.g., LDL) across the membrane via receptor-mediated endocytosis is ineffective, the material remains in the tissue fluids or blood and increases in concentration. This failure of receptor-mediated endocytosis causes some human diseases. For example, the human genetic disease familial hypercholesterolemia involves LDL receptors that are defective or missing entirely. People with this condition have life-threatening cholesterol levels in their blood because their cells cannot clear the chemical from their blood by receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Learning Activity: Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

This activity provides an overview of receptor-mediated endocytosis for LDL particles.

- Watch the video “Receptor Mediated Endocytosis” (1:53 min) by Richard Posner (2015). Make your own notes and keep a copy for study purposes.

- Watch the more detailed linked videos below:

- “Receptor Mediated Endocytosis p1” (1:03 min) by Mena Missa (2014).

- “Receptor Mediated Endocytosis p2” (1:04 min) also by Mena Missa (2014).

- Answer the following questions:

- Summarize the composition of LDL particles and all types of molecules involved in their internalization.

- Use the provided information in Figure 16 to draw your own diagram of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. What type of materials can be internalized by this process? Unit 3, Topic 3 will revisit clathrin.

Exocytosis

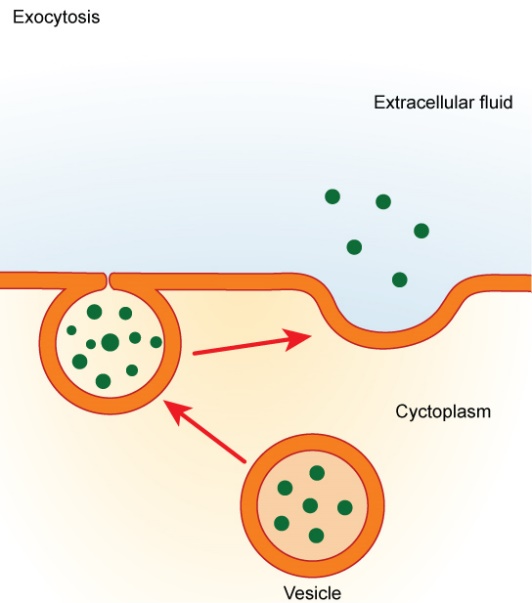

Exocytosis exports molecules out of cells that would otherwise not pass easily through the plasma membrane. In the process, secretory vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents extracellularly. Materials, such as proteins and lipids embedded in the membranes of the vesicles, become part of the plasma membrane when fusion between it and the vesicles occurs (Figure 17).

Fusion is a membrane process where two distinct lipid bilayers merge their hydrophobic cores, producing one interconnected structure. Membrane fusion involving vesicles is the mechanism by which endocytosis and exocytosis occur. Common processes involving membrane fusion include a sperm fertilizing an egg, separating membranes in cell division, transporting waste products, and releasing neurotransmitters (Figure 18). Artificial membranes, such as liposomes, can also fuse with cellular membranes. Fusion is also important for transporting lipids from the synthesis point inside the cell to the membrane for use. Fusion can also govern pathogen entry, as many bilayer-coated viruses use fusion proteins to enter host cells.

Exocytosis has five main stages. The first stage is called vesicle trafficking. This stage involves moving the vesicle containing the material over a significant distance to dispose of it. The next stage is vesicle tethering, which links the vesicle to the cell membrane by biological material at half the diameter of a vesicle. The third stage, vesicle docking, involves connecting and holding the vesicle and cell membranes together. The fourth stage is vesicle priming, which includes all molecular rearrangements and protein and lipid modifications after the initial docking. In some cells, there is no priming. The final stage, vesicle fusion, involves merging the vesicle membrane with the target membrane. This action releases unwanted materials into the space outside the cell.

Plant and animal cells constantly use exocytosis to excrete waste. Other cell processes that use exocytosis include secreting proteins (e.g., enzymes, peptide hormones, and antibodies), flipping the plasma membrane, positioning integral membrane proteins (IMPs) or proteins biologically attached to the cell, and recycling receptors (molecules that intercept signals) bound to the plasma membrane.

Unit 3 will cover the detailed molecular mechanisms of receptor-mediated endocytosis, vesicular trafficking within the cell, and exocytosis.

Key Concepts and Summary

The combined gradient affecting an ion includes its concentration and electrical gradients. A positive ion, for example, might diffuse into a new area down its concentration gradient; however, if it diffuses into an area of net positive charge, its electrical gradient hampers its diffusion. When dealing with ions in aqueous solutions, one must consider the electrochemical and concentration gradient combinations rather than just the concentration gradient alone. Living cells need certain substances that exist inside the cell in concentrations greater than they exist in the extracellular space. Moving substances up their electrochemical gradients requires energy from the cell.

Active transport uses energy stored in ATP (or other sources such as light) to fuel this transport. Active transport of small molecular-sized materials uses integral proteins in the cell membrane to move the materials. These proteins are analogous to pumps. Some pumps that carry out primary active transport couple directly with ATP to drive their action. In co-transport (or secondary active transport), energy from primary transport can move another substance into the cell and up its concentration gradient. Maintaining cellular homeostasis requires many transport systems to work together, especially for glucose levels. Bacterial active transporters are essential for cell viability, virulence, and pathogenicity.

Endocytosis includes phagocytosis, pinocytosis, and receptor-mediated endocytosis. Bulk transport involves large particles, such as macromolecules, parts of cells, or whole cells, becoming engulfed by other cells in a process called phagocytosis. In phagocytosis, a portion of the membrane invaginates and flows around the particle, eventually pinching off and leaving the particle entirely enclosed by a plasma membrane envelope. Vesicle contents broken down by the cell are used as food or dispatched.

Pinocytosis is a similar process on a smaller scale. The plasma membrane invaginates and pinches off, producing a small envelope containing fluid from outside the cell. Pinocytosis imports substances that the cell needs from the extracellular fluid. The cell expels waste in a similar but reverse manner: it pushes a membranous vacuole to the plasma membrane, allowing the vacuole to fuse with the membrane and incorporate itself into the membrane structure, releasing its contents to the exterior in a process called exocytosis.

Key Terms

active transport

the method of transporting material that requires energy

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) domain

the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family is a group of proteins which bind and hydrolyse ATP in order to transport substances across cellular membranes

caveolin

protein that coats the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane and participates in the process of liquid uptake by potocytosis

clathrin

protein that coats the inward-facing surface of the plasma membrane and assists in the formation of specialized structures, like coated pits, for phagocytosis

concentration gradient

area of high concentration adjacent to an area of low concentration

electrochemical gradient

a gradient produced by the combined forces of the electrical gradient and the chemical gradient

electrogenic pump

pump that creates a charge imbalance

endocytosis

a type of active transport that moves substances, including fluids and particles, into a cell

endosome

an endocytic vacuole through which molecules internalized during endocytosis pass en route to lysosomes

exocytosis

a process of passing material out of a cell

GLUT protein

integral membrane protein that transports glucose

glycolysis

process of breaking glucose into two three-carbon molecules with the production of ATP and NADH

phagocytosis

a process that takes particulate matter like macromolecules, cells, or cell fragments that the cell needs from the extracellular fluid; a variation of endocytosis

pinocytosis

a process that takes solutes that the cell needs from the extracellular fluid; a variation of endocytosis

potocytosis

variation of pinocytosis that uses a different coating protein (caveolin) on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane

primary active transport

active transport that moves ions or small molecules across a membrane and may create a difference in charge across that membrane

pump

active transport mechanism that works against electrochemical gradients

receptor-mediated endocytosis

a variant of endocytosis that involves the use of specific binding proteins in the plasma membrane for specific molecules or particles

secondary active transport

movement of material that is due to the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport

sodium-potassium pump (also Na+/K+ ATPase)

membrane-embedded protein pump that uses ATP to move Na+ out of a cell and K+ into the cell

Long Descriptions

Primary Active Transport – The Na+-K+ pump mobes Na+ using the energy of ATP hydrolysis to establish a concentration gradient of Na+.

Secondary Active Transport – Na+, moving with the concentration gradient established by the Na+-K+ pump, drives the transport of glucose against its concentration gradient. [Return to Figure 8]

Figure 11 Image Description: Diabetes symptoms can present in many ways, including:

- Central nervous system – lethargy, stupor, excessive thirst, and excessive hunger.

- Eyes – blurred vision.

- Breath – smell of acetone.

- Gastric – nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

- Respiratory – hyperventilation.

- Urinary – frequent urination and glucose in urine.

- Systemic – weight loss. [Return to Figure 11]

Figure 12 Image Description: The cycle of blood glucose regulation is as follows:

- Blood glucose level rises.

- The pancreas releases insulin.

- In response to insulin, target cells take up glucose, and the liver converts glucose to glycogen.

- Blood glucose level falls.

- The pancreas releases glucagon.

- In response to glucagon, the liver breaks down glycogen and releases glucose into the blood. [Return to Figure 12]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 5.16 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 5.17 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 5.18 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 3.25 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 5.19 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: 1l7v opm by Andrei Lomize (2007), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 7: Abc importer by Alexanderaloy and Stargonzales (2009), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 8: Figure 5.20 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 7-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 7.20 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: Figure 37.10 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 37.11 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 3.26 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: Figure 7-11 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Figure 7-12 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 16: Itrafig2 by Grant BD and Sato M (2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 2.5 license.

- Figure 17: Figure 3.27 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal] from OpenStax Concepts of Biology (Fowler et al. 2013) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 18: Figure 7-13 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Alexanderaloy, Stargonzales. 2009. Abc importer [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2014 Mar 19; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31687519.

Alila Medical Media. Diabetes type 1 and type 2, animation [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Dec 8, 3:45 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XfyGv-xwjlI.

Amgen Biotech Experience. 2019. Diabetes types 1 and 2 [article]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 Mar 23, accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:87afc74d:html:1.

Amgen Biotech Experience. 2019. Making a human therapeutic protein in bacteria [Image]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 Apr 1; accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:cd4fc8ca:lx_image:1.

Amgen Biotech Experience. 2019. Producing human therapeutic proteins in bacteria [article]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 Apr 3, accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:63a516c7:html:1.

Anatomy and physiology (Boundless). 2023. Westchester (IL): Follett; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless).

Anatomy and physiology (Boundless). 2023. Westchester (IL): Follett; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. 29.12C: cystic fibrosis. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Anatomy_and_Physiology/Anatomy_and_Physiology_(Boundless)/29%3A_APPENDIX_A%3A_Diseases_Injuries_and_Disorders_of_the_Organ_Systems/29.12%3A_Respiratory_Diseases_and_Disorders/29.12C%3A_Cystic_Fibrosis.

Andrew Vinal. Cotransport [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Sep 23, 1:53 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsggCqbsVxs.

Andrey K. Glucose transporters [Video]. YouTube. 2015 May 17, 14:21 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i9S5_KZa_Is.

Biology Brainery. ABC transporters [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Jan 27, 7:56 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CaD4lp09hCA.

Boston University Global Development Policy Center. 2021. Insulin imports fail to meet many countries’ needs [blog]. Boston (MA): Boston University. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2021/08/02/insulin-imports-fail-to-meet-many-countries-needs/#:~:text=Despite%20being%20a%20100%2Dyear,are%20import%2Ddependent%20for%20insulin.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 7.2: glycolysis, Chapter 7.7: regulation of cellular respiration, Chapter 37.3: regulation of body processes. Figures 5.16 to 5.20, 7.20, 37.10, 37.11. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Cystic Fibrosis Canada. 2023. Canadian CF Registry. Toronto (ON): Cystic Fibrosis Canada. https://www.cysticfibrosis.ca/our-programs/cf-registry.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/1-introduction.

Fowler S, Roush R, Wise J. 2013. Concepts of biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 3.25, 3.27. https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/3-6-active-transport.

GHC Biology. Active transport: primary & secondary [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Aug 13, 4:43 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmXCswxPjQg.

Ghezzi C, Loo DDF, Wright EM. 2018. Physiology of renal glucose handling via SGLT1, SGLT2 and GLUT2. Diabetologia. 61(10):2087-2097. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-018-4656-5. doi:10.1007.s00125-018-4656-5.

Grapin-Bottom A, Boes K. 2021. New miniature organ to understand human pancreas development [article]. Dresden (Germany): Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.mpg.de/16940441/new-miniature-organ-to-understand-human-pancreas-development.

Grant BD, Sato M. 2006. Itrafig2 [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2012 Jan 8; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17968876.

Greenhill C, Kriebs A, Maennich D, Minton K, Sargent J, Starling S. 2021. Nature milestones in diabetes [interactive timeline]. Berlin (Germany): Springer Nature; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.nature.com/immersive/d42859-021-00002-5/index.html.

Homework Clinic. Types of transport – uniport, antiport and symport (glucose and Na+K+ transporters) [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Apr 23, 2:09 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFXUl0MnLlk.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figures 7-8, 7-11, 7-12, 7-13. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/a762477a-0cf1-4ff5-ae0c-0a86c45ea15e.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Bulk transport. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Dec 1]. AP®︎/College Biology, Lesson 5: membrane transport. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/membrane-transport/a/bulk-transport.

Khan Academy. Glucose insulin and diabetes [Video]. Khan Academy. 2011 Apr 4, 7:23 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.khanacademy.org/test-prep/mcat/organ-systems/hormonal-regulation/v/glucose-insulin-and-diabetes.

Khan Academy. Uniporters, symporters, and antiporters | biology | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Aug 3, 7:12 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-aGYytZ7K7M.

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball).

Kimball JW. 2022. Biology (Kimball). Medford (MA): Tufts University & Harvard; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 2.5: cholesterol. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Biology_(Kimball)/02%3A_The_Molecules_of_Life/2.05%3A_Cholesterol.

Koepsell H. 2020. Glucose transporters in the small intestine in health and disease. Pflüg Arch. 472(9):1207-1248. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00424-020-02439-5. doi:10.1007/s00424-020-02439-5.

JJ Medicine. Glucose transporters (GLUTs and SGLTs) – biochemistry lesson [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Feb 11, 7:33 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzN0geHb86I.

LabXchange. 2021. Macrophages and phagocytosis [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:533ec428:lx_simulation:1.

Lomize A. 2014. 1l7v opm [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2014 Jul 20; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1l7v_opm.png.

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. MKBN211: introductory microbiology (Bezuidenhout). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Northwest_University/MKBN211%3A_Introductory_Microbiology_(Bezuidenhout).

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. MKBN211: introductory microbiology (Bezuidenhout). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 3.3.3: ABC transporters. https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Northwest_University/MKBN211%3A_Introductory_Microbiology_(Bezuidenhout)/03%3A_Cell_Structure_of_Bacteria_Archaea_and_Eukaryotes/3.03%3A_Transport_Across_the_Cell_Membrane/3.3.03%3A_ABC_Transporters.

Mena missa. Receptor mediated endocytosis p1 [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Mar 22, 1:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OejK9KAfFCY.

Mena missa. Receptor mediated endocytosis p2 [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Mar 22, 1:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TuuwLLlKYGU.

Nature Video. The discovery of insulin [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Jun 18, 5:44 minutes. [acccessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gk1D4VgM8jY.

Nature Video. Diabetes in sub-saharan Africa [Video]. LabXchange. 2022 Jul 6, 6:23 minutes. [updated 2023 Feb 22, accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:5aab1131:video:1.

Nonstop Neuron. Primary active transport vs secondary active transport [Video]. YouTube. 2021 May 3, 3:50 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-iBdwtQn4Q.

Our World in Data. 2021. Diabetes prevalence [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:5996bde6:lx_simulation:1.

Richard Posner. 13 3 receptor mediated endocytosis [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Jul 6, 1:53 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLbjLWNA5c0.

RicochetScience. The sodium-potassium pump [Video]. YouTube. 2016 May 23, 2:26 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bPFKDdWlCg.

Ryan Abbott. ABC transporters [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Jun 18, 2:00 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LwSKgrdomPM.

Sharma A, Kaplan WA. 2021. Insulin imports fail to meet many countries’ needs. Science. 373(6554):494-497. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abg4374. doi:10.1126/science.abg4374.

Vargas E, Podder V, Sepulveda MAC. 2022. Physiology, glucose transporter type 4. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; [accessed 2022 Dec 1]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537322/.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2022. ATP-binding cassette transporter. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [accessed 2022 Dec 26]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=ATP-binding_cassette_transporter&oldid=1129685893.

Wondersofchemistry. Carbohydrate (glucose) absorption [Video]. YouTube. 2018 May 29, 7:17 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AXbvfBfqdtY.

1 Wright EM, Hirayama BA, Loo DF. 2007. Active sugar transport in health and disease. J Intern Med. 261(1):32-43. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01746.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01746.x.

Zedalis J, Eggebrecht J. 2018. Biology for AP ® courses. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction.

Zedalis J, Eggebrecht J. 2018. Biology for AP ® courses. Houston (TX): OpenStax. [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 5.3: active transport. https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/5-3-active-transport.

the method of transporting material that requires energy

area of high concentration adjacent to an area of low concentration

a type of active transport that moves substances, including fluids and particles, into a cell

a gradient produced by the combined forces of the electrical gradient and the chemical gradient

active transport mechanism that works against electrochemical gradients

active transport that moves ions or small molecules across a membrane and may create a difference in charge across that membrane

membrane-embedded protein pump that uses ATP to move Na+ out of a cell and K+ into the cell

movement of material that is due to the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport

pump that creates a charge imbalance

the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family is a group of proteins which bind and hydrolyse ATP in order to transport substances across cellular membranes

process of breaking glucose into two three-carbon molecules with the production of ATP and NADH

integral membrane protein that transports glucose

an endocytic vacuole through which molecules internalized during endocytosis pass en route to lysosomes

a process that takes particulate matter like macromolecules, cells, or cell fragments that the cell needs from the extracellular fluid; a variation of endocytosis

a process that takes solutes that the cell needs from the extracellular fluid; a variation of endocytosis

a process of passing material out of a cell

a variant of endocytosis that involves the use of specific binding proteins in the plasma membrane for specific molecules or particles

protein that coats the inward-facing surface of the plasma membrane and assists in the formation of specialized structures, like coated pits, for phagocytosis

protein that coats the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane and participates in the process of liquid uptake by potocytosis

variation of pinocytosis that uses a different coating protein (caveolin) on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane