4.2 Signal Propagation and Response

Introduction

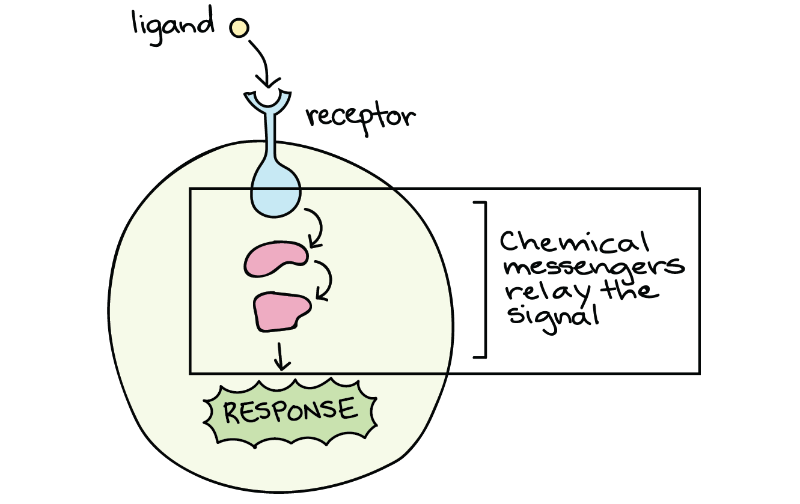

Unit 4, Topic 1 introduced the general principle of various signalling mechanisms and some signalling molecules and their receptors (Figure 1). Is the signalling process complete once a signalling molecule (ligand) from one cell binds to a receptor on the target cell? The answer may be yes for intracellular receptors that bind their ligand inside the cell and directly activate genes. In most cases, though, the answer is no. For receptors on the cell membrane, the signal must pass on through other molecules in the cell in a sort of cellular game of “telephone.” The chains of molecules that relay signals inside a cell are known as intracellular signal transduction pathways. Unit 4, Topic 2 will dig deeper into some specific characteristics and mechanisms of intracellular signal transduction pathways.

Cell signalling pathways vary a lot. Signals (aka ligands) and receptors come in many varieties, and binding can trigger a wide range of signal relay cascades inside the cell, from short and simple to long and complex. Despite these differences, signalling pathways share a common goal: to produce a cellular response. In some cases, a cellular response can be described at both the molecular and macroscopic (large-scale or visible) levels:

- Molecular level changes can include an increase in the transcription of specific genes or the activity of enzymes.

- Macroscopic level changes can occur in the outward behaviour or appearance of the cell (e.g., cell growth or cell death) caused by molecular changes.

The results of signalling pathways are incredibly varied; they depend on the type of cell involved and the external and internal conditions. Unit 4, Topic 2 describes a small sampling of responses to signalling that happen at both the “micro” and “macro” levels.

Unit 4, Topic 2 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 4, Topic 2, you will be able to:

- Explain how the binding of a ligand initiates signal transduction throughout a cell.

- Recognise the role of phosphorylation in the transmission of intracellular signals.

- Evaluate the role of second messengers in signal transmission.

- Describe how signalling pathways direct protein expression, cellular metabolism, and cell growth.

- Discuss the role of transcription factors in gene regulation.

- Explain how enhancers and repressors regulate gene expression.

- Identify the function of PKC in signal transduction pathways.

- Recognise the role of apoptosis in the development and maintenance of a healthy organism.

| Unit 4, Topic 2—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions from Unit 4, Topic 2 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Gene expression essentials. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell signals (…the whole journey). | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Connecting growth factor signalling with gene regulation. | 25 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cellular mechanism of hormone action. | 25 |

| Complete Learning Activity: The apoptotic pathways and the caspase cascade. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Variety of cellular responses. | 25 |

| Complete Learning Activity: H5P activities (4 total). | 10 |

Ligand-Receptor Binding Initiates a Signalling Pathway

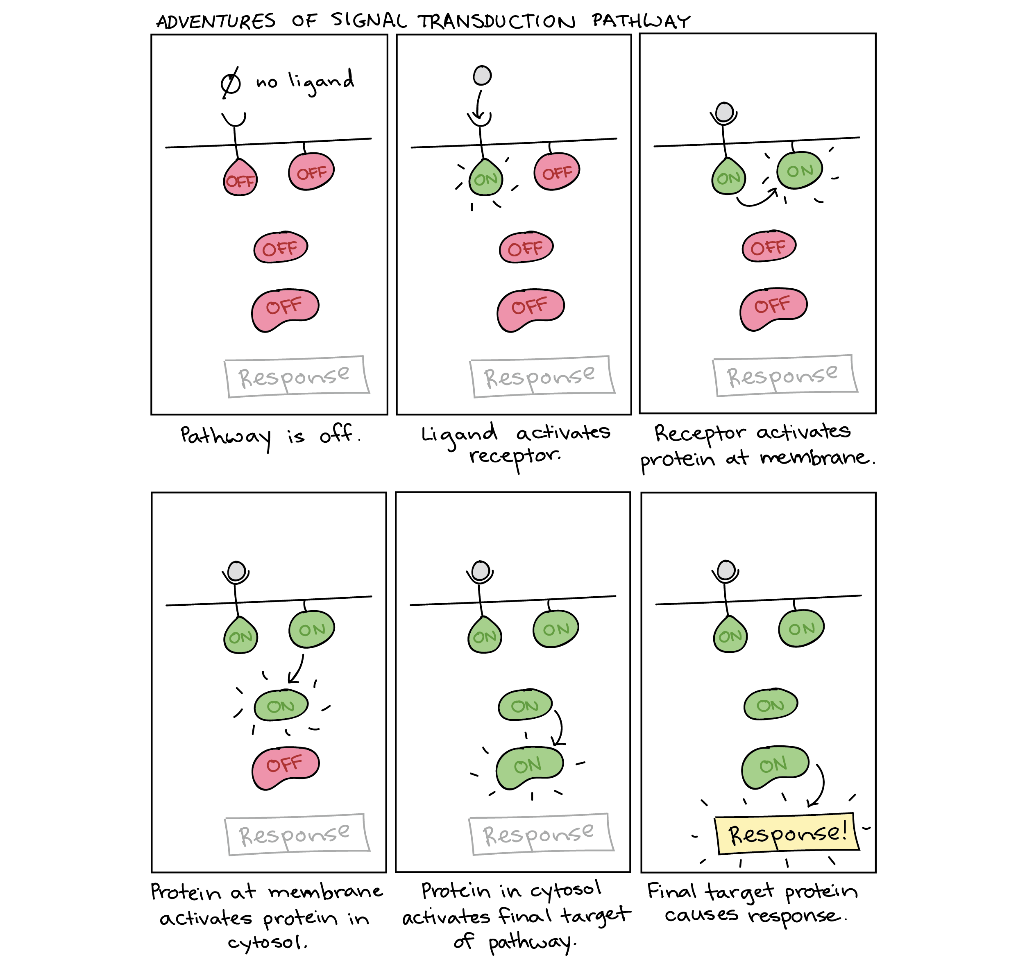

After the ligand binds to the cell-surface receptor, activating the receptor’s intracellular components sets off a chain of events called a signalling pathway (sometimes called a signalling cascade). For example, the receptor may turn on another signalling molecule inside the cell, which, in turn, activates its own target. This chain reaction can eventually change the cell’s behaviour or characteristics, as shown in the cartoon below (Figure 2).

Because of the directional flow of information, the term upstream often describes molecules and events that come earlier in the relay chain, while downstream can describe those that come later (relative to a particular molecule of interest). For instance, the receptor is downstream of the ligand but upstream of the proteins in the cytosol (Figure 2). Many signal transduction pathways amplify the initial signal so that one ligand molecule can lead to activating many molecules of a downstream target. The molecules that relay a signal are often proteins. However, non-protein molecules like ions and phospholipids can also play important roles.

Methods of Intracellular Signalling

The induction of a signalling pathway depends on an enzyme modifying a cellular component. Numerous enzymatic modifications can occur, and they are recognised in turn by the next component downstream. The following are some of the more common events in intracellular signalling.

Phosphorylation

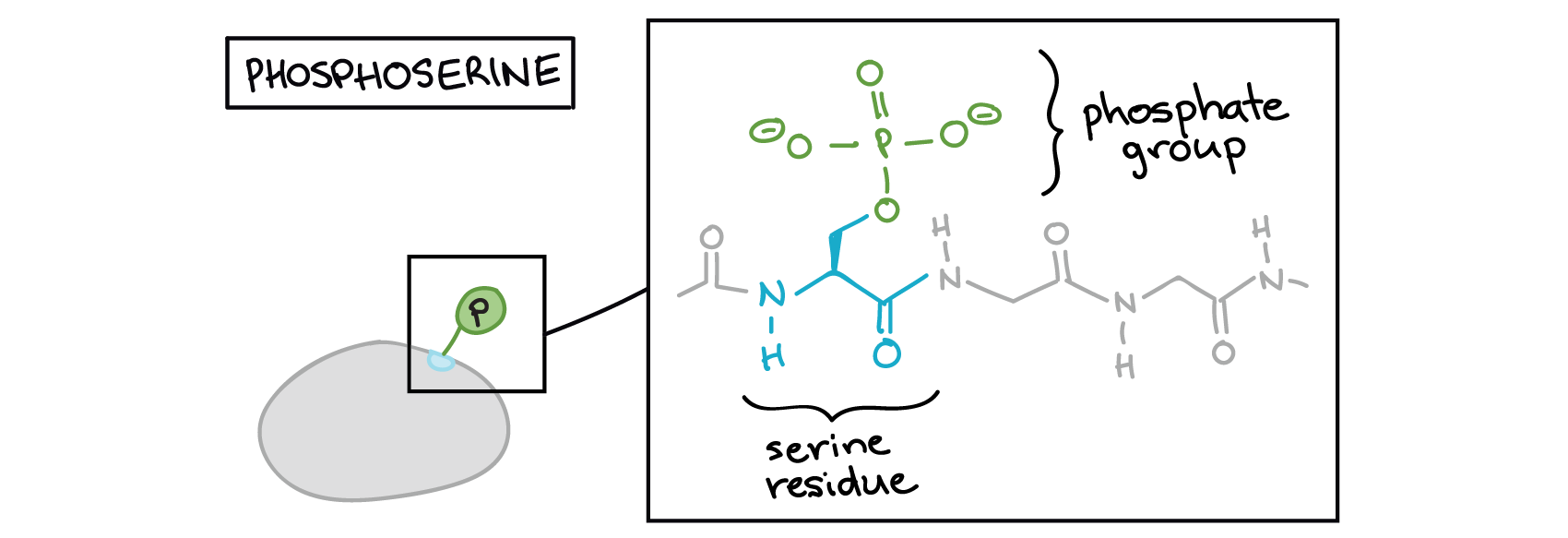

Figure 2 above features a bunch of blobs (signalling molecules) labelled as “on” or “off.” What does it actually mean for a blob to be on or off? Proteins can be activated or inactivated in a variety of ways. However, one of the most common tricks for altering protein activity is adding a phosphate group (PO43−) to one or more sites on the protein, a process called phosphorylation.

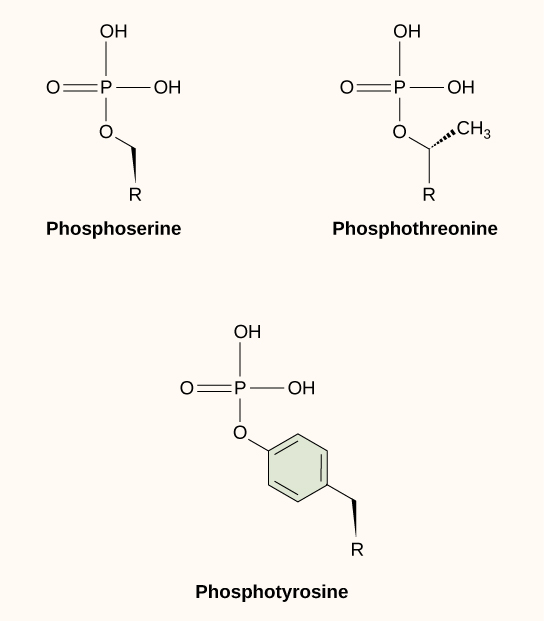

The phosphate can be added to a nucleotide, such as GMP, to form GDP or GTP. Phosphates are also often added to serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues of proteins, where they replace the hydroxyl group of the amino acid (Figure 3 and Figure 4). An enzyme called a kinase catalyzes the phosphate transfer. Various kinases have names based on the substrate they phosphorylate. Phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues often activates enzymes. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues can either affect the activity of an enzyme or create a binding site that interacts with downstream components in the signalling cascade. Phosphorylation may activate or inactivate enzymes, and the reversal of phosphorylation, dephosphorylation by a phosphatase, will reverse the effect.

Phosphorylation often acts as a switch, but its effects vary among proteins. Sometimes, phosphorylation makes a protein more active (e.g., increasing catalysis or letting it bind to a partner). In other cases, phosphorylation may inactivate the protein or cause it to break down.

Self-Check

How does a phosphate group do all this? How can adding one little phosphate group have such a significant effect on protein behaviour?

Show/Hide answer.

The answer comes down to basic biochemistry: adding a phosphate group attaches a big cluster of negative charges to the protein surface. This negative charge may attract or repel amino acids within the protein, changing its shape. Because a protein’s function depends on its structure, changing the shape of the protein may alter its ability to work as an enzyme, either increasing or decreasing activity.

Alternatively, phosphorylation may provide a docking site for an interaction partner (say, one with a bunch of positive charges) or prevent another partner from binding.

These are just a few examples, but they give a sense of how the phosphate group can directly affect the chemical behaviour of a protein.

From “How does a phosphate group do all this?” Signal Relay Pathways (Khan Academy [date unknown]). CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

Phosphorylation Example: Epidermal Growth Factor Signalling Cascade

To get a better sense of how phosphorylation works, consider a real-life signalling pathway example using this technique: growth factor signalling. Specifically, consider the part of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) pathway that acts through a series of kinases to produce a cellular response.

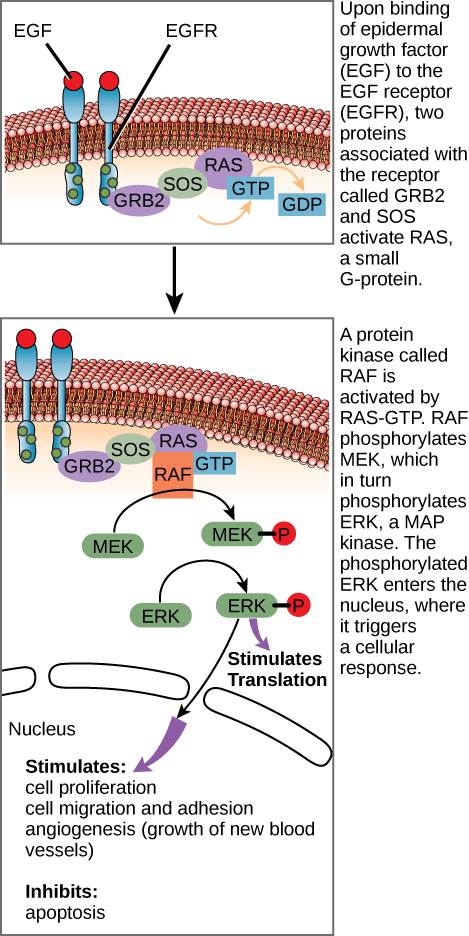

Figure 6 shows several components in the epidermal growth factor (EGF) signalling pathway. When the ligand (EGF) binds to its receptor (EGFR), conformational changes occur and affect the receptor’s intracellular domain. Conformational changes of the extracellular domain upon ligand binding can propagate through the intramembrane region of the receptor and lead to activation of the intracellular domain or its associated proteins. In this case, ligand binding causes dimerization of the EGFR, which means that two receptors bind to each other to form a stable complex called a dimer. A homodimer is a chemical compound formed when two identical molecules join together. When receptors bind in this manner, it enables their intracellular domains to come into close contact and activate each other.

The intracellular domains of each receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) dimer have kinase enzymatic activity that is only active after binding the signalling molecule to the cell surface, which brings the two subunits together. Upon dimerization, the RTK completes autophosphorylation by transferring phosphate groups to tyrosine residues within the receptor itself. The phosphate groups on the intracellular domains provide docking sites for adaptor proteins that initiate an intracellular signalling cascade (Figure 6).

Phosphorylation (marked as a P) is important at many stages of this pathway.

- When growth factor ligands bind to their receptors, the receptors pair up and act as kinases, attaching phosphate groups to one another’s intracellular tails. Please review Unit 4, Topic 1 Enzyme-linked receptors.

- The activated receptors trigger a series of events that allow two proteins (GRB2 and SOS) to interact with and activate the small G-protein RAS.

- RAS-GTP activates a kinase called RAF. Active RAF phosphorylates and activates MEK, which phosphorylates and activates the ERK MAPK. ERK stands for extracellular signal-regulated kinases, and it belongs to the family of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) that operate within signalling cascades that transmit extracellular signals to their intracellular targets.

- The ERKs phosphorylate and activate a variety of target molecules. These include transcription factors, like c-Myc, as well as cytoplasmic targets. The activated targets promote cell growth and division.1

The RAF, MEK, and ERKs put together make up a three-tiered kinase signalling pathway called a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. A mitogen is a signal that causes cells to undergo mitosis or divide. Because they play a central role in promoting cell division, the genes encoding the growth factor receptor, RAF, and c-Myc are all proto-oncogenes, meaning that overactive forms of these proteins are associated with cancer. C-Myc is a well-known protein that can lead to cancer when it is too active (“too good” at promoting cell division).2,3

Second Messengers

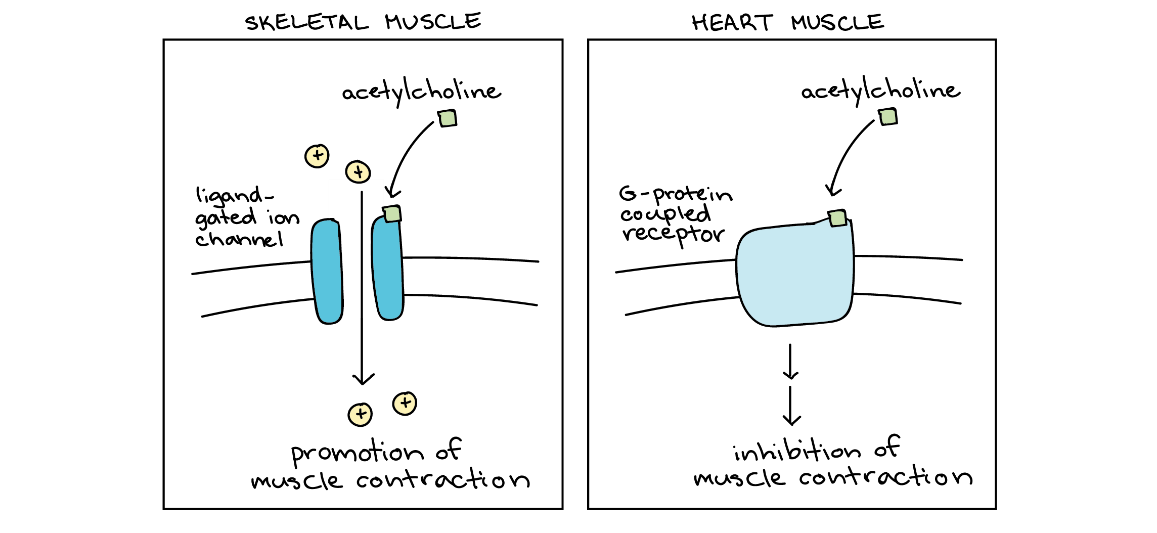

Second messengers are small molecules that propagate a signal after the binding of the signalling molecule (the ligand being the “first messenger”) to the receptor initiates it. These molecules help spread a signal through the cytoplasm by altering the behaviour of certain cellular proteins. Second messengers include Ca2+ ions; cyclic AMP (cAMP), a derivative of ATP; and inositol phosphates, made from phospholipids.

Calcium Ions

The calcium ion is a widely used second messenger. The free Ca2+ concentration within a cell is very low because ion pumps in the plasma membrane continuously remove it using ATP. For signalling purposes, Ca2+ is stored in cytoplasmic vesicles (e.g., smooth endoplasmic reticulum) or accessed from outside the cell. When signalling occurs, ligand-gated calcium ion channels allow the higher Ca2+ levels present outside the cell (or in intracellular storage compartments) to flow into the cytoplasm, raising the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. The response to the increase in Ca2+ varies and depends on the cell type involved. For example, in the β-cells of the pancreas, Ca2+ signalling releases insulin, and in muscle cells, an increase in Ca2+ leads to muscle contractions.

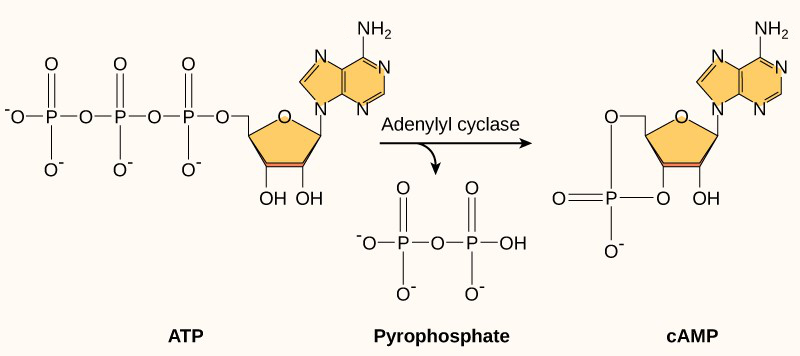

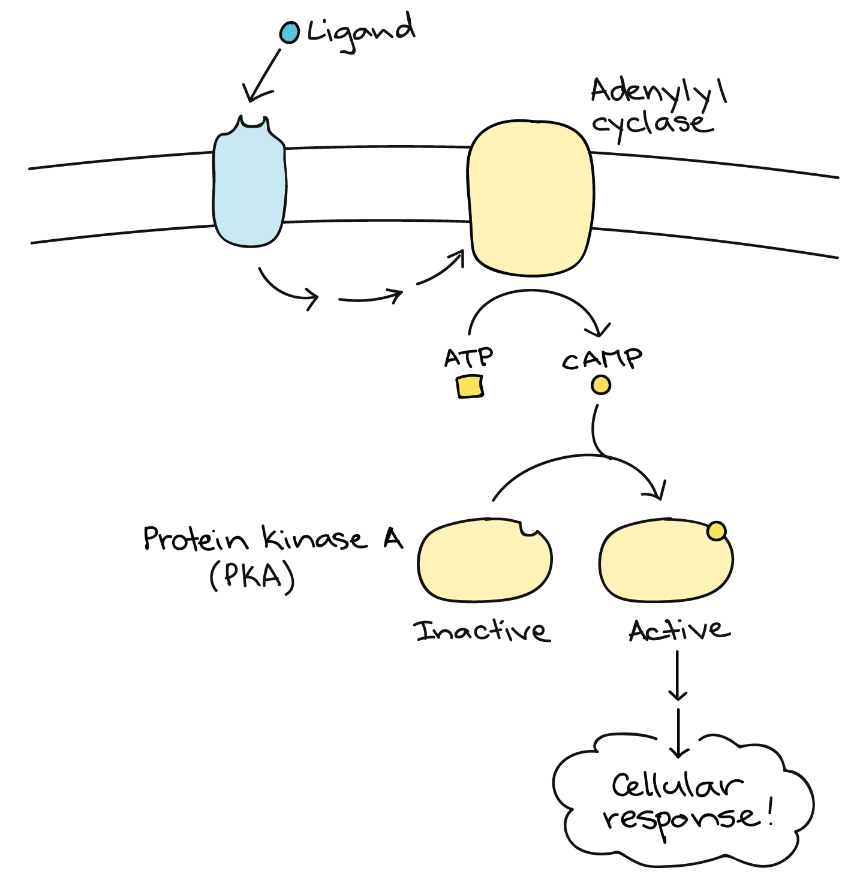

Cyclic AMP (cAMP)

Another second messenger utilized in many different cell types is cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP or cAMP). The enzyme adenylyl cyclase synthesizes cyclic AMP from ATP (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The main role of cAMP in cells is to bind to and activate an enzyme called cAMP-dependent kinase (or protein kinase A). Protein kinase A regulates many vital metabolic pathways; it phosphorylates serine and threonine residues of its target proteins, activating them in the process. Protein kinase A is in many different types of cells, and the target proteins in each kind of cell are different. Differences give rise to the variation of the responses to cAMP in different cells.

Inositol Phosphates

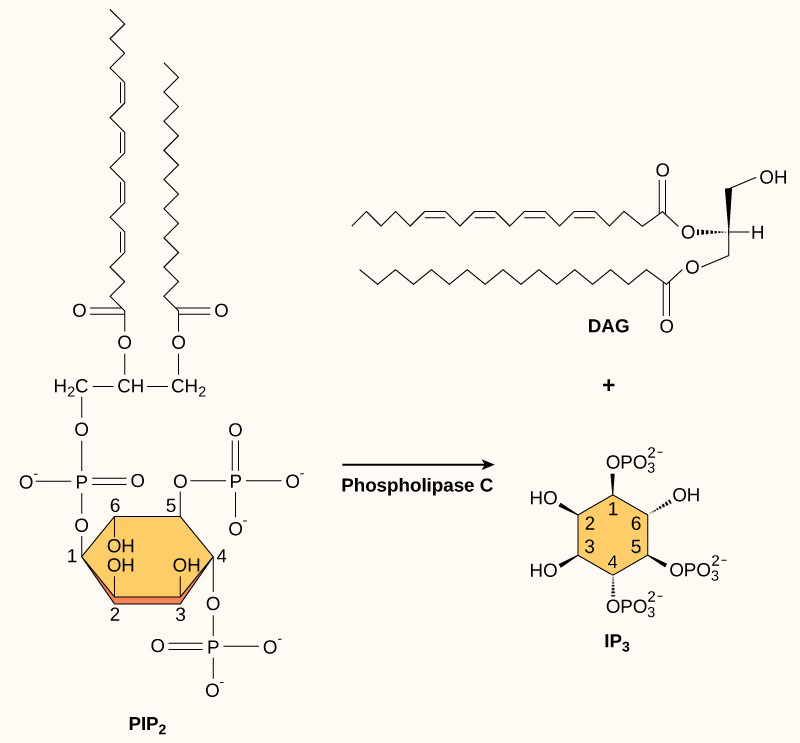

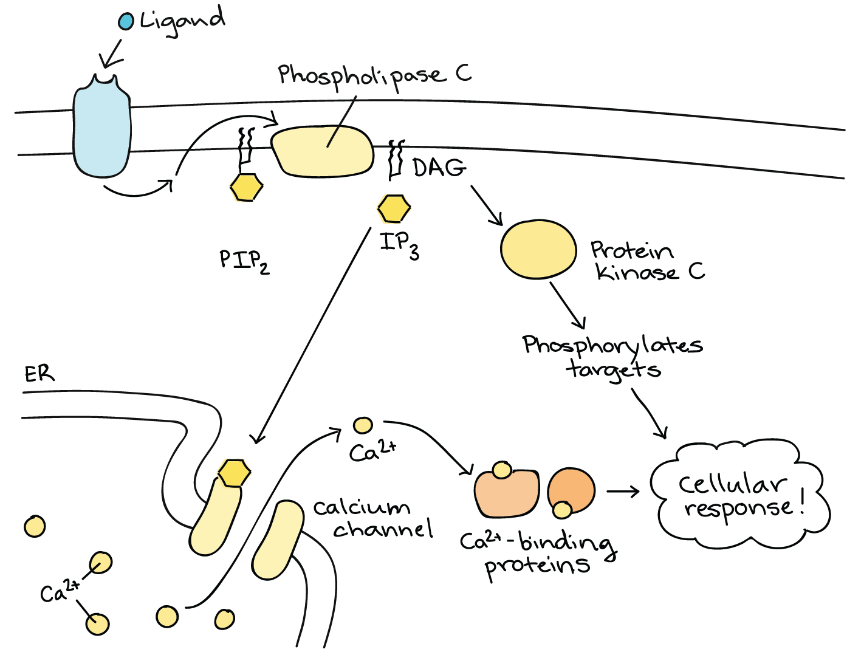

Although plasma membrane phospholipids are usually thought of as structural components of the cell, they can also be important participants in signalling. Phospholipids called phosphatidylinositols can be phosphorylated and snipped in half, releasing two fragments that both act as second messengers.

Inositol phospholipids are lipids present in small concentrations in the plasma membrane that can turn into second messengers. Because these molecules are membrane components, they are located near membrane-bound receptors and can easily interact with them. Phosphatidylinositol (PI) is the main phospholipid that plays a role in cellular signalling. Enzymes known as kinases phosphorylate PI to form PI-phosphate (PIP) and PI-bisphosphate (PIP2).

The enzyme phospholipase C cleaves PIP2 to form diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol triphosphate (IP3) (Figure 9). These products from cleaving PIP2 serve as second messengers.

DAG remains in the plasma membrane and activates protein kinase C, which then phosphorylates serine and threonine residues in its target proteins (Figure 10). IP3 diffuses into the cytoplasm and binds to ligand-gated calcium channels in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum to release Ca2+ that continues the signal cascade.

Pathway Complexity

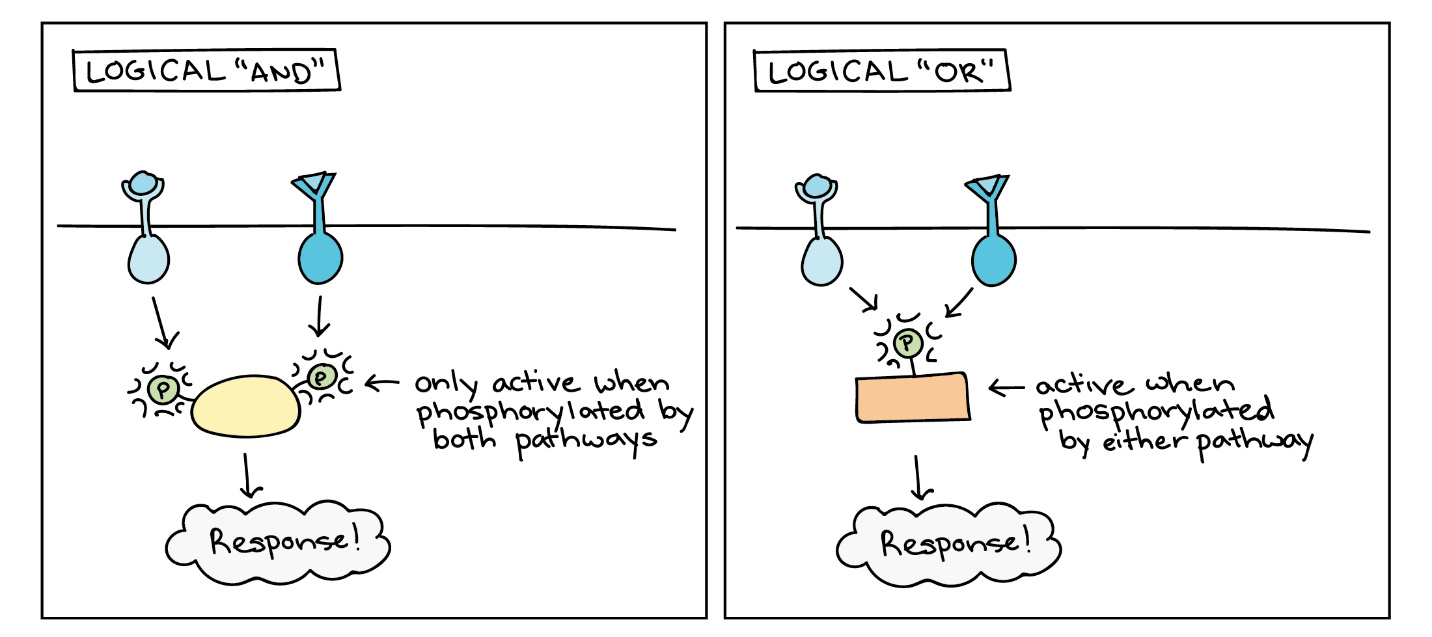

Signalling pathways can get very complicated very quickly because most cellular proteins can affect different downstream events (different pathways) depending on the conditions within the cell (Figure 11). A single pathway can branch off toward different endpoints based on the interplay between two or more signalling pathways, and the same ligands often initiate different signals in different cell types. This variation in response is due to differences in protein expression in different cell types. Another complicating element is signal integration of the pathways, in which signals from two or more different cell-surface receptors merge to activate the same response in the cell. This process can ensure that multiple external requirements are met before a cell commits to a specific response.

Enzymatic cascades can also amplify the effects of extracellular signals. At the initiation of the signal, a single ligand binds to a single receptor. However, activating a receptor-linked enzyme can activate many copies of a component in the signalling cascade, which amplifies the signal.

Another source of complexity in signalling is that the same signalling molecule may produce different results depending on what molecules are already present in the cell (Figure 12).

These are just a few examples of the complexities that make signalling pathways challenging but fascinating to study. Cell-cell signalling pathways, especially the EGF pathway, are a focus of study for researchers developing new drugs against cancer (see Unit 4, Topic 4).

Response to the Signal

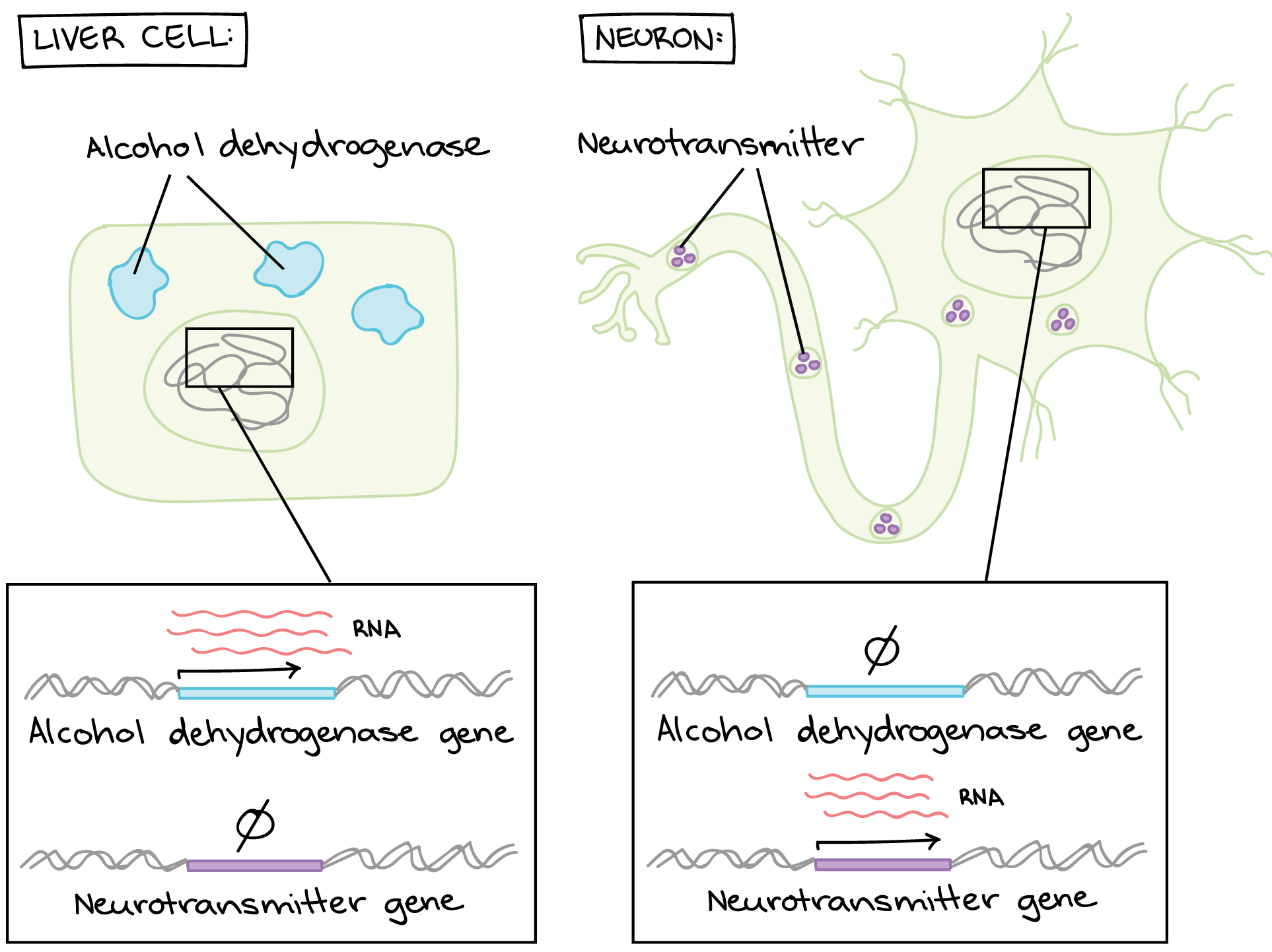

The human body contains hundreds of different cell types, from immune cells to skin cells to neurons. Almost all these cells contain the same set of DNA instructions – so why do they look so different and do such different jobs? The answer is differential gene regulation.

Gene regulation key points are as follows:

- Gene regulation is the process of controlling which genes in a cell’s DNA are expressed (used to make a functional product such as a protein).

- Different cells in a multicellular organism may express very different sets of genes, even though they contain the same DNA.

- The set of genes expressed in a cell determines the set of proteins and functional RNAs it contains, giving it its unique properties.

- In eukaryotes like humans, gene expression involves many steps, and gene regulation can occur at any of these steps. However, many genes are regulated primarily at the level of transcription.

Gene Regulation Makes Cells Different

Gene regulation is how a cell controls which genes, out of the many genes in its genome, are “turned on” (expressed). Thanks to gene regulation, each cell type in a body has a different set of active genes — despite the fact that almost all the cells in the body contain the same DNA. These different gene expression patterns cause various cell types to have different sets of proteins, making each cell type uniquely specialized to do its job.

For example, one job of the liver is to remove toxic substances like alcohol from the bloodstream (Figure 13). Liver cells do this by expressing the gene-encoding subunits (pieces) of an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase. This enzyme breaks alcohol down into a non-toxic molecule. The neurons in a person’s brain do not remove toxins from the body, so they keep these genes unexpressed (or “turned off”). Similarly, liver cells do not send signals using neurotransmitters, so they keep neurotransmitter genes turned off.

Many other genes are expressed differently between liver cells and neurons (or any two cell types in a multicellular organism).

How do Cells “Decide” Which Genes To Turn On?

The above question can be tricky. Many factors can affect which genes a cell expresses. Different cell types express different sets of genes, as seen above. However, two different cells of the same type may also have different gene expression patterns depending on their environment and internal state. In broad terms, information from inside and outside the cell determines a cell’s gene expression.

- Examples of information from inside the cell are the proteins it inherited from its mother cell, whether its DNA is damaged, and how much ATP it has

- Examples of information from outside the cell are chemical signals from other cells, mechanical signals from the extracellular matrix, and nutrient levels

How do these cues help a cell “decide” what genes to express? Cells do not make decisions in the sense that a person would. Instead, they have molecular pathways that convert information — such as the binding of a chemical signal to its receptor — into a change in gene expression.

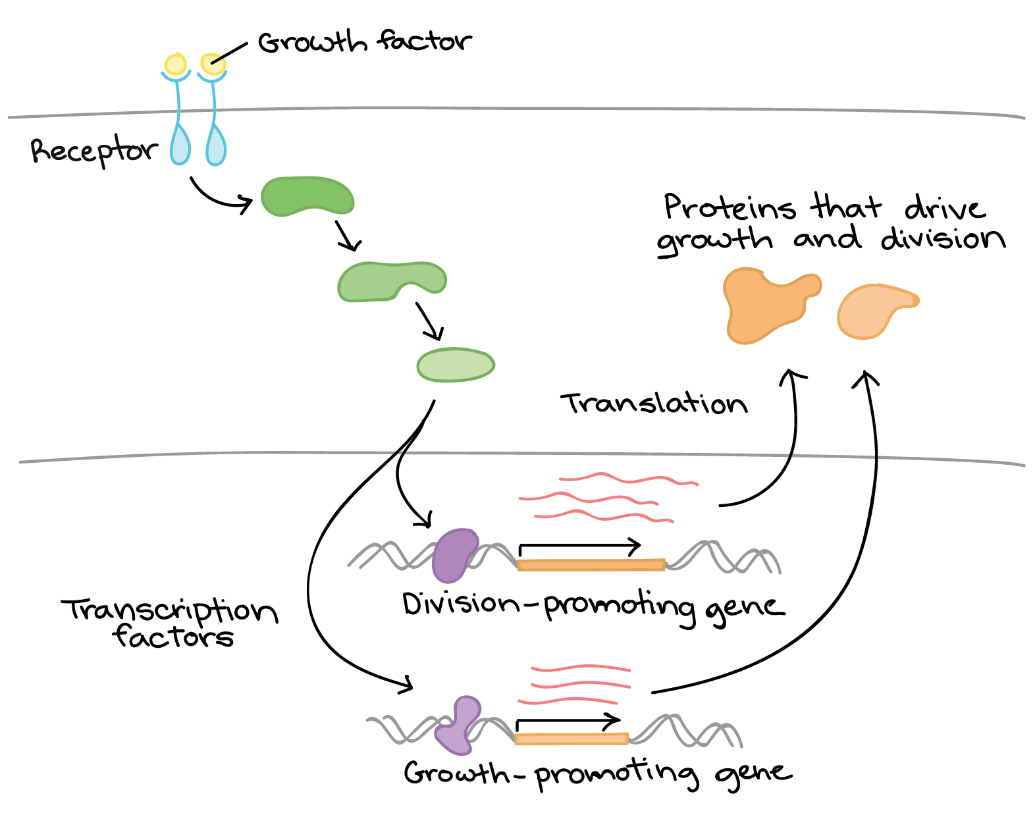

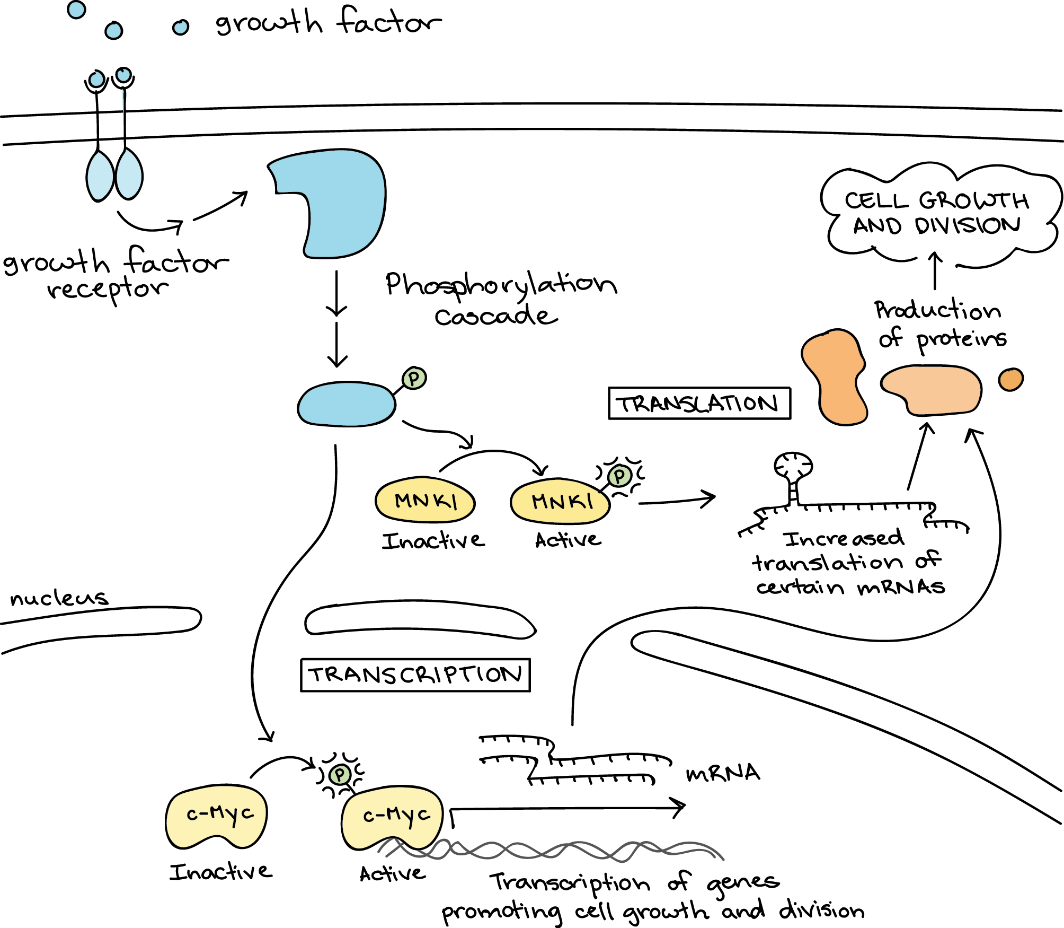

For example, consider how cells respond to growth factors in terms of gene regulation (Figure 14). A growth factor is a chemical signal sent from a neighbouring cell that instructs a target cell to grow and divide. It could be said that the cell “notices” the growth factor and “decides” to divide, but how do these processes occur? The mechanism can be summarized as follows:

- The cell detects the growth factor through the physical binding of the growth factor to a receptor protein on the cell surface.

- Binding of the growth factor causes the receptor to change shape, triggering a series of chemical events in the cell that activate proteins called transcription factors.

- The transcription factors bind to specific DNA sequences in the nucleus and cause transcription of genes related to cell growth and division.

- The products of these genes are various types of proteins that make the cell divide (drive cell growth and/or push the cell forward in the cell cycle).

Growth factor signalling is complex and involves the activation of a variety of targets, including both transcription factors and non-transcription factor proteins. Unit 4, Topic 3 and Topic 4 will further discuss how growth factor signalling works. Growth factor signalling is just one example of how a cell can convert a source of information into a change in gene expression. There are many others, which is why understanding the logic of gene regulation is an area of ongoing research in biology today.

Transcription Factors

Transcription factors are proteins that regulate the transcription of genes — that is, their copying into RNA on the way to making a protein. The human body contains many transcription factors. So does the body of a bird, tree, or fungus. Transcription factors help ensure that the right cells express the right genes at the right time.

Transcription factor key points are as follows:

- Transcription factors are proteins that help turn specific genes “on” or “off” by binding to nearby DNA.

- Transcription factors that are activators boost a gene’s transcription. Repressors decrease transcription.

- Groups of transcription factor binding sites called enhancers and silencers can turn a gene on/off in specific parts of the body.

- Transcription factors allow cells to perform logic operations and combine different sources of information to “decide” whether to express a gene.

Gene expression is when a gene in DNA is “turned on” (used to make the protein it specifies). Not all the genes in a person’s body are turned on at the same time or in the same cells or parts of the body. This is known as differential gene expression.

For many genes, transcription is the key on/off control point:

- If a cell does not transcribe a gene, the cell cannot use that gene to make a protein.

- If a cell does transcribe a gene, the cell will likely use the gene to make a protein (expressed). Generally, the more a cell transcribes a gene, the more protein it makes.

Various factors control how much a cell can transcribe a gene. For instance, how tightly the gene’s DNA winds around its supporting proteins to form chromatin can affect its availability for transcription.

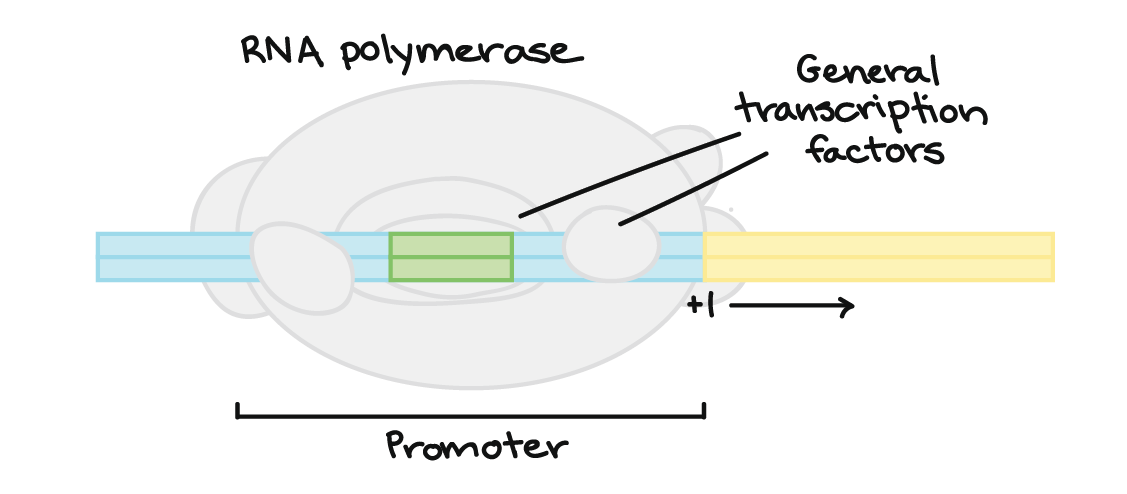

What must happen for a cell to transcribe a gene? The enzyme RNA polymerase, which makes a new RNA molecule from a DNA template, must attach to the gene’s DNA in a spot called the promotor (Figure 15). In bacteria, RNA polymerase attaches right to the DNA of the promoter. However, in humans and other eukaryotes, there is an extra step. RNA polymerase can attach to the promoter only with the help of proteins called basal (general) transcription factors. They are part of the cell’s core transcription toolkit, needed for transcribing any gene.

However, many transcription factors are not the general kind. Instead, a large class of transcription factors controls the expression of specific, individual genes. For instance, a neuron-specific transcription factor might activate only a set of genes needed in certain neurons.

A typical transcription factor binds to DNA at a certain target sequence. Once it is bound, the transcription factor makes it either harder or easier for RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter of the gene.

Self-Check

The binding of _ is required for transcription to start.

- A protein

- DNA polymerase

- RNA polymerase

- A transcription factor

Show/Hide answer.

c. RNA polymerase

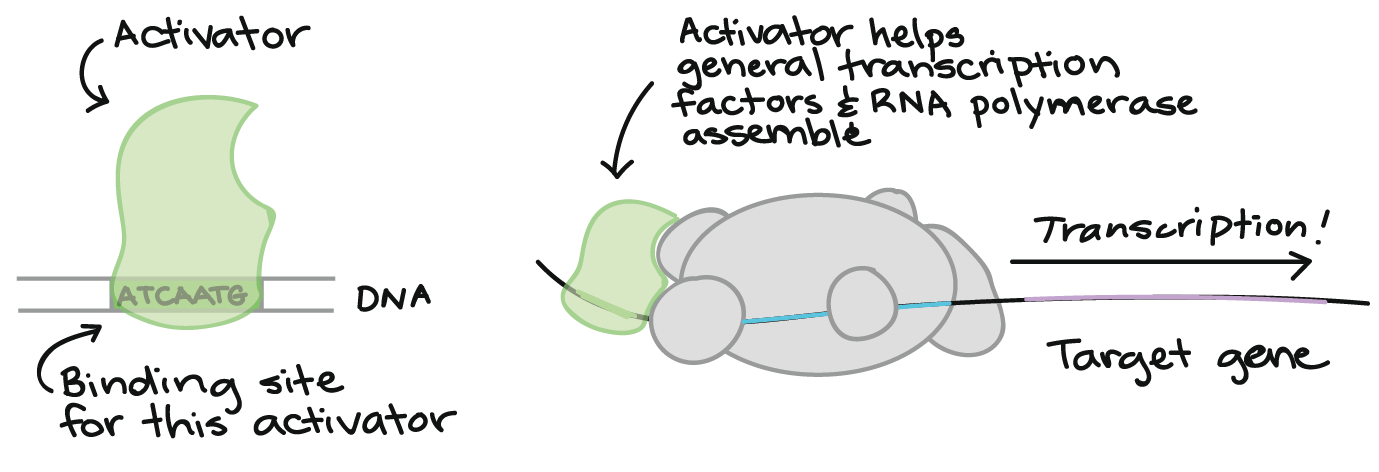

Activators

Some transcription factors activate transcription (Figure 16). For instance, they may help the general transcription factors and/or RNA polymerase bind to the promoter, as shown in the diagram below.

Repressors

Other transcription factors repress transcription (Figure 17). This repression can work in a variety of ways. As one example, a repressor may interfere with the basal transcription factors or RNA polymerase, making it so they cannot bind to the promoter or begin transcription.

Binding Sites

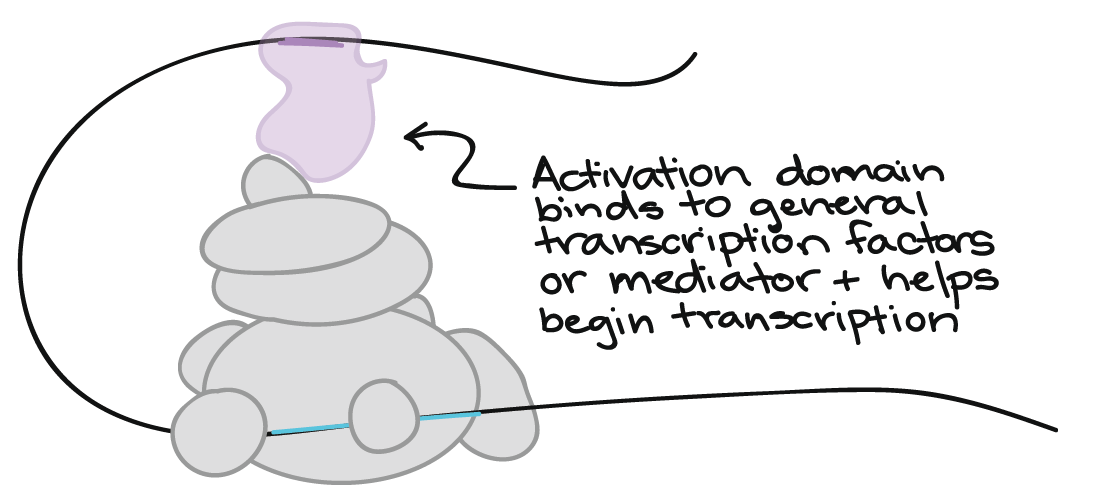

Binding sites for transcription factors are often close to a gene’s promoter (see Figure 16). However, they can also be found in other parts of the DNA, sometimes very far away from the promoter, and still affect the transcription of the gene (Figure 18).

The flexibility of DNA is what allows transcription factors at distant binding sites to do their job. The DNA loops like cooked spaghetti to bring far-off binding sites and transcription factors close to general transcription factors or mediator proteins. In Figure 18, an activating transcription factor bound at a far-away site helps RNA polymerase bind to the promoter and start transcribing.

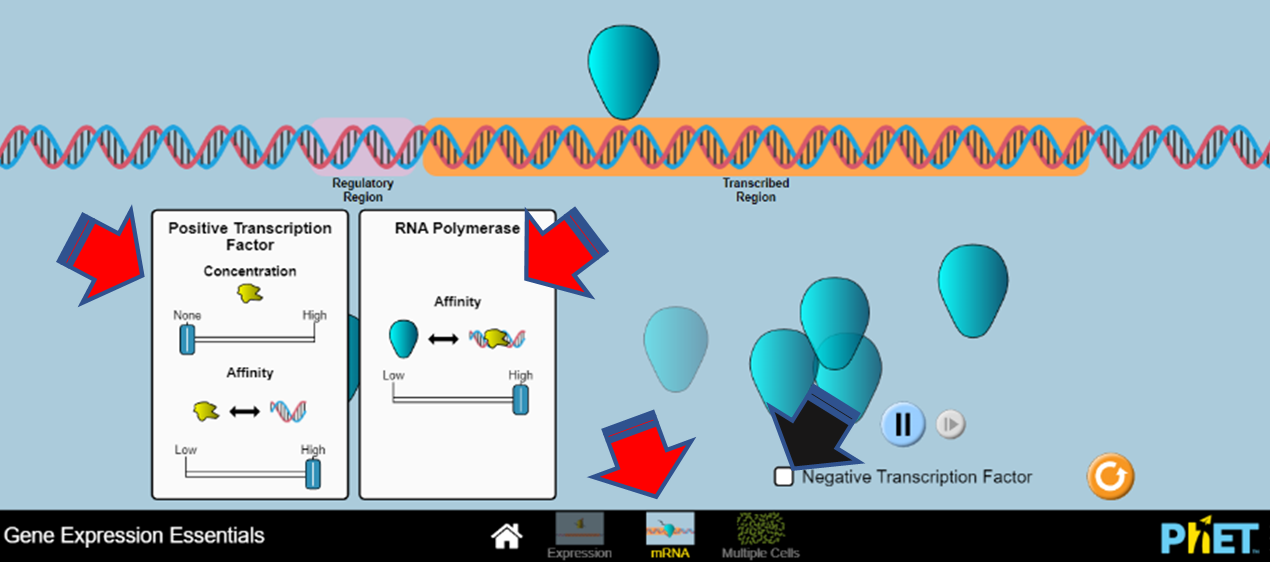

Learning Activity: Gene Expression Essentials

- Go to the LabXchange interactive “Gene Expression Essentials” by PhET (2019).

- In the ‘Expression’ section, choose the components you think are necessary from the ‘Biomolecule Toolbox’ to express three different genes. Drag each translated protein into the ‘Your Protein Collection’ box.

- Click on the ‘mRNA’ section at the bottom of the screen (red arrow). Manipulate the components in the ‘Positive Transcription Factor’ and ‘RNA Polymerase’ boxes (red arrows). Click on ‘Negative Transcription Factor’ (black arrow) to see what happens to the production of your mRNA (Figure 19).

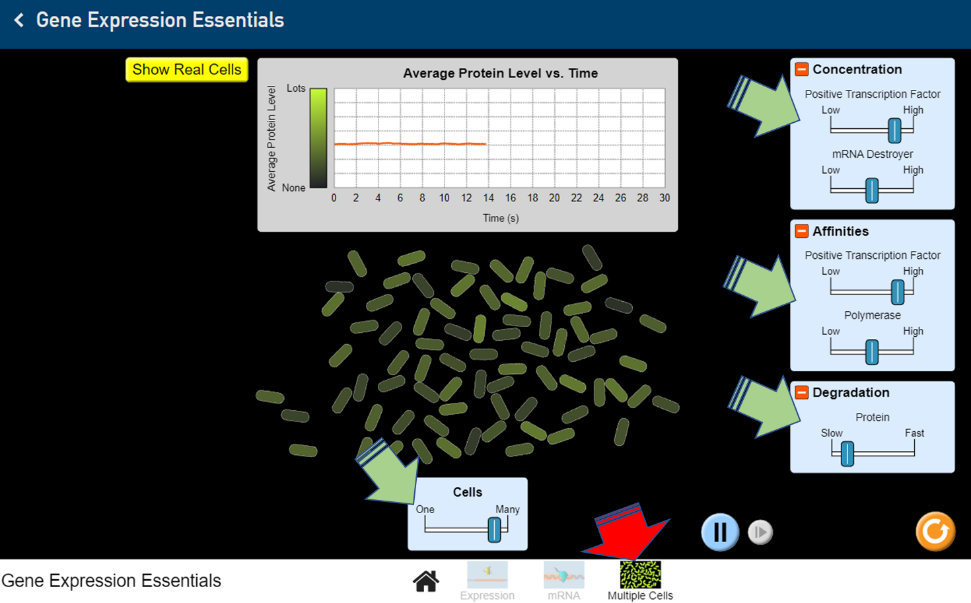

Figure 19: Screenshot of the LabXchange interactive “Gene Expression Essentials” gene transcription simulation. (PhET 2019/LabXchange) CC BY 4.0 - Click on ‘Multiple Cells’ (red arrow). Adjust the number of cells as well as the nuclear components (green arrows). Describe what happens to the average protein levels over time (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Screenshot of the LabXchange “Gene Expression Essentials” protein level simulation. (PhET 2019/LabXchange) CC BY 4.0

Signalling and Translation

Many signalling pathways cause a cellular response that changes gene expression. C-Myc activating target genes is such an example (Figure 21). As discussed above, gene expression is the process in which a cell uses information from a gene to produce a functional product, typically a protein. It involves two main steps: transcription and translation. Transcription makes an RNA transcript (copy) of a gene’s DNA sequence. Translation reads information from the RNA to make a protein.

Self-Check

Wait, what are DNA and RNA?

Show/Hide answer.

Here is a little more detail about how gene expression happens in eukaryotic cells:

- The deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence of a gene is copied (transcribed) into ribonucleic acid (RNA), a step called transcription. The RNA is modified in the nucleus to make a functional messenger RNA (mRNA).

- The mRNA leaves the nucleus and enters the cytosol. Once there, it directs protein synthesis, indicating which amino acids to add to the chain. This step is called translation.

Learn more about gene expression in “DNA replication and RNA transcription and translation” (15:23 min) by Khan Academy (2014).

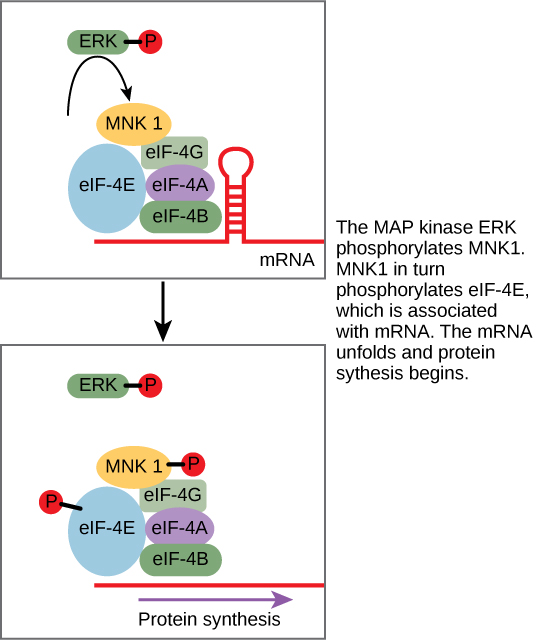

While some signal transduction pathways regulate RNA transcription, others regulate protein translation from mRNA. An example of a protein that regulates translation is the MAPK ERK. ERK is activated in a phosphorylation cascade when EGF binds EGFR (see Figure 6). Phosphorylated ERK phosphorylates and activates a serine/threonine protein kinase called MNK1, which, in turn, regulates protein translation (Figure 22).

Active MNK1 increases the rate of mRNA translation, especially for certain mRNAs that fold back on themselves to make hairpin structures (which would usually block translation). Many key genes regulating cell division and survival have mRNAs that form hairpin structures; MNK1 allows these genes to be expressed at high levels, driving growth and division.4,5

Notably, neither c-Myc nor MNK1 is a “final responder” in the growth factor pathway. Instead, these regulatory factors, and others like them, promote or repress the production of other proteins (the orange blobs in Figure 21) more directly involved in carrying out cell growth and division.

MAPK signalling pathways are widespread in biology and found in a wide range of organisms, from humans to yeast to plants. The similarity of MAPK cascades in diverse organisms suggests that this pathway emerged early in the evolutionary history of life and was already present in a common ancestor of modern-day animals, plants, and fungi.

Self-Check

In certain cancers, the cancer inhibits the GTPase activity of the RAS G-protein. This means that the RAS protein can no longer hydrolyze GTP into GDP.

What effect would this have on downstream cellular events?

Show/Hide answer.

ERK would become permanently activated, resulting in cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and the growth of new blood vessels.

Learning Activity: Cell Signals (…the Whole Journey)

- Watch the video “Cell Signals” (14:15 min) by DNA Learning Center (2010).

- Answer the following questions while watching the video:

- What type of cells produce proteins that help to repair the cellular damage at the cut site?

- Which small cell fragments release protein messengers at the site? What do these messengers do?

- Where do the protein messengers (growth factors) from the platelets go?

- What happens next?

- Where does the activated intracellular messenger go? What is its journey like? How do you think it knows where to go?

- What does it do at its destination?

- What is the final result of this journey?

- What is the journey of the newly translated proteins?

- Why do you think a growth factor must be secreted from the cell in which it was made?

Learning Activity: Connecting Growth Factor Signalling With Gene Regulation

Fibroblast growth factor signalling is essential for the development of the nervous system. The receptors for fibroblast growth factors are receptor tyrosine kinases that may signal through the MAPK, phosphoinositol 3-kinase, and phospholipase Cγ pathways. How do fibroblast growth factor receptors and related pathways interact to regulate gene expression? Scientists used optic tract development in the frog Xenopus laevis as an example to see how fibroblast growth factor signalling regulates the expression of axon guidance genes, sema3a and slit1, which code for proteins that steer the path of retinal axons toward the target, the optic tectum.

- Read the paper “The Expression of Key Guidance Genes at a Forebrain Axon Turning Point Is Maintained by Distinct Fgfr Isoforms but a Common Downstream Signal Transduction Mechanism” by Yang et al. (2019).

- Answer the following questions:

- There are four fibroblast growth factor receptors, and they do not all work the same way. How do each of these receptors regulate the axon guidance genes?

- Does each major pathway downstream from where fibroblast growth factor receptor activates upregulate or downregulate the axon guidance genes?

- Explain how amino acid mutations generate constitutively active or dominant negative forms of signalling enzymes Akt and BRAF.

- What are some weaknesses in the paper?

Cellular Metabolism

Some signalling pathways produce a metabolic response in which metabolic enzymes in the cell become more or less active. To see how this works, consider adrenaline signalling in muscle cells (Figure 23). Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone (produced by the adrenal gland) that readies the body for short-term emergencies. If a person is nervous before a test or competition, their adrenal gland is likely pumping out epinephrine.

When epinephrine binds to its receptor on a muscle cell (a G-protein-coupled receptor), it triggers a signal transduction cascade that produces the second messenger, cAMP. The first enzyme is glycogen phosphorylase. The job of this enzyme is to break down glycogen into glucose. Glycogen is a storage form of glucose, and when energy is needed, the body breaks down glycogen. Phosphorylation activates glycogen phosphorylase, causing lots of glucose to be released.

The second enzyme that gets phosphorylated is glycogen synthase. This enzyme helps build up glycogen, and phosphorylation inhibits its activity. This inhibition ensures that the body does not build new glycogen molecules when it currently needs to break down glycogen.

Through regulating these enzymes, a muscle cell rapidly gets a large, ready pool of glucose molecules. The glucose is available for use by the muscle cell in response to a sudden surge of adrenaline—the “fight or flight” response.

Learning Activity: Cellular Mechanism of Hormone Action

- Watch the following videos:

- “Cellular mechanism of hormone action | Endocrine system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy” (8:22 min) by Khanacademymedicine (2013).

- “Signal Transduction Pathways” (9:24 min) by Bozeman Science (2011).

- Answer the following questions:

- List the players in a pathway in which a hormone works through a secondary messenger.

- What are the first two steps in the process and the consequences?

- What happens to the G-protein? What is the consequence?

- What happens to adenylyl cyclase after it’s activated? What is the consequence?

- Describe signal amplification.

- Why do some hormones use secondary messengers?

- Why can some hormones act as primary messengers? What are two examples of such hormones?

- Why can only one epinephrine molecule create so many glucose molecules?

- How does transcription get activated in this pathway?

Cell Death

Cell death can broadly be divided into two categories: unprogrammed cell death and programmed cell death. Unprogrammed cell death, also termed necrosis, is a disordered process that damages surrounding tissue. This damage occurs when certain toxins (e.g., brown recluse spider venom) or injury cause cell membranes to rupture. Hydrolytic enzymes and low-pH organelles, such as lysosomes and endosomes, are then released into the extracellular environment. This release causes inflammation and, in extreme cases, turns the damaged tissue red or black.

In contrast to necrosis, programmed cell death (termed apoptosis) is a highly ordered process.6 Apoptosis briefly initiates when internal or external signals indicate that a cell needs removing from the population. This process triggers “cell suicide,” which degrades intracellular contents. Morphologically, apoptosis characteristics include the shrinking of the cell, changes in the cell membrane (with the formation of small blebs known as “apoptotic bodies”), shrinking of the nucleus, chromatin condensation, and fragmentation of DNA. Macrophages and other phagocytic cells recognise this signal and use phagocytosis to remove apoptotic cells. The intracellular contents of the dying cells are not released, and there is no inflammation or damage to the surrounding tissue. Apoptosis regulates the growth of normal tissues and removes unwanted cells in a controlled manner.

Other important large-scale outcomes of cell signalling include cell migration, cell identity changes, and apoptosis induction. When a cell is damaged, superfluous, or potentially dangerous to an organism, a cell can initiate a mechanism to trigger programmed cell death. This response allows a cell to die in a controlled manner that prevents potentially damaging molecules from being released inside the cell.

Many internal checkpoints monitor a cell’s health; if the checkpoint detects abnormalities, a cell can spontaneously initiate apoptosis. For example, most normal animal cells have receptors that interact with the extracellular matrix, a network of glycoproteins that provides structural support for cells in an organism. The binding of cellular receptors to the extracellular matrix initiates a signalling cascade within the cell. However, if the cell moves away from the extracellular matrix, the signalling ceases, and the cell undergoes apoptosis. This system keeps cells from travelling through the body and proliferating out of control, as happens with tumour cells that metastasize. However, in some cases, the cell’s usual checks and balances fail, such as with a viral infection or uncontrolled cell division due to cancer.

Another example of external signalling leading to apoptosis occurs in T-cell development. T-cells are immune cells that bind to foreign macromolecules and particles, and they target them for destruction by the immune system. Normally, T-cells do not target “self” proteins (those of their own organism), a process that can lead to autoimmune diseases. To develop the ability to discriminate between self and non-self, immature T-cells undergo screening to determine whether they bind to so-called self proteins. If the T-cell receptor binds to self proteins, the cell initiates apoptosis to remove the potentially dangerous cell.

Caspases are a family of enzymes that control apoptosis. These are cysteine proteases that cleave proteins next to aspartate residues when they become activated. When a cell receives an apoptotic signal, the procaspases become active and begin the process of protein degradation, starting with the cleavage of lamins in the nuclear envelope, protein kinases, transcription factors, snRP proteins, and inhibitors of special DNases, which can fragment the nuclear DNA (Figure 24).

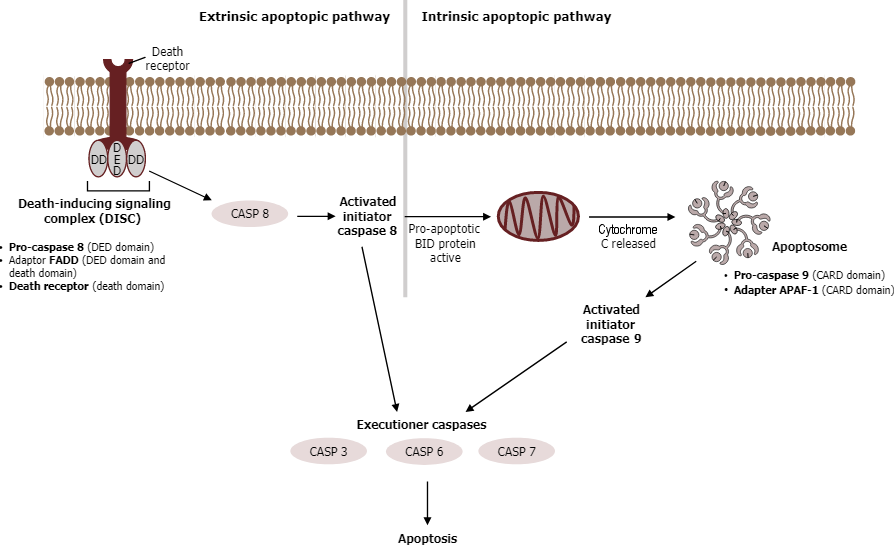

The extrinsic pathway for apoptosis does not involve cytochrome c; it becomes triggered on the cell surface by ligands that bind to receptors of the tumour necrosis factor family (TNFR, “death receptors”). These receptors are known as pro-cell death receptors and include Fas receptors, which are present on the plasma membrane of most cells in the body. When Fas ligands bind to cell Fas receptors, receptor trimerization takes place via the adaptor protein FADD (“Fas-associated death domain”), activating the initiator caspases 8 and 10 inside the cell and setting the apoptotic process in motion.

Genotoxic (DNA damage) or oxidative stress triggers the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Aided by Bcl proteins, chemical stress makes the outer mitochondrial membrane leaky. As a result, mitochondrial proteins reach the cytoplasm. Cytochrome c then triggers the caspase cascade by binding to the adaptor protein Apaf1 and promoting the formation of an apoptosome. An apoptosome is a wheel-shaped heptamer that recruits the initiator procaspase 9 and activates it to caspase 9. After converting procaspase 9 to caspase 9 within the apoptosome, caspase 9 cleaves the pro-domains from a small population of procaspases 3, 6, and 7 proteins to form active caspases 3, 6, and 7 (Figure 24). These active caspases then cleave pro-domains from other pro-caspases, increasing the number of active caspases within the cell. Thus, a cascade effect occurs, called a caspase cascade (also called a proteolytic cascade), after the initial activation of one set of caspases. Ultimately, the active caspases break down chromatin and proteins within the cell.

The Bcl protein family includes proapoptotic proteins (Bax, Bak, and Bim) and proteins that inhibit apoptosis (including Bcl2). Extracellular growth factors ensure inactivation of Bad or replication of Bcl2, thus preventing apoptosis. The anti-apoptosis protein Bcl2 inhibits cell death by sequestering cytochrome c in the mitochondria. In contrast, the pro-apoptosis proteins Bak and Bax promote the release of the cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, initiating apoptosis. This specific mechanism of action is still not fully understood. However, experts believe that Bak and Bax form a pore in the mitochondria, allowing the release of cytochrome c. Conversely, Bcl2 may either prevent Bax/Bak pore formation and/or serve as a “plug” to prevent cytochrome c diffusion through the pore.

Why must some cells die for the good of the embryo? Apoptosis is essential for normal embryological development. In some cases, apoptosis during development occurs in a very predictable way. For example, the worm C. elegans has 131 cells that die by apoptosis as the worm develops from a single cell to an adult (and the exact ones are known).1 Cloning apoptotic genes of C. elegans and their characterization have led to considerable understanding of the molecular events of apoptosis and to the identification of mammalian homologues of the apoptotic effectors.

Apoptosis is also essential for normal embryological development. In vertebrates, for example, early stages of development include forming web-like tissue between individual fingers and toes (Figure 25). These unneeded cells must be eliminated during normal development, enabling fully separated fingers and toes to form. A cell signalling mechanism triggers apoptosis, which destroys the cells between the developing digits. Other apoptosis examples during normal development include a tadpole losing its tail as it turns into a frog and certain species removing unneeded neurons from neural circuits in the brain and invertebrate nerve cord.7

Learning Activity: The Apoptotic Pathways and the Caspase Cascade

- Watch the following videos:

- “Apoptosis | Cell division | Biology | Khan Academy” (10:47 min) by Khan Academy (2016).

- “What is Apoptosis?” The Apoptotic Pathways and the Caspase Cascade” (3:58 min) by Elvire Thouvenot-Nitzan (2016).

- Answer the following questions:

- Describe the etymology of the word apoptosis.

- Is apoptosis a default pathway, or is it intentional? Explain.

- What is the difference between necrosis and apoptosis?

- What are two examples of apoptosis that occur early in developing organisms?

- What are the two pathways by which apoptosis can occur?

- Describe the extrinsic pathway.

- Describe the intrinsic pathway.

- How is apoptosis related to cancer?

Termination of the Signal Cascade

The aberrant signalling often seen in tumour cells proves that terminating a signal at the appropriate time can be just as important as initiating a signal. One method to stop a specific signal is by degrading or removing the ligand so it can no longer access its receptor. One reason that hydrophobic hormones like estrogen and testosterone trigger long-lasting events is because they bind carrier proteins. These proteins allow the insoluble molecules to be soluble in blood, but they also protect the hormones from degradation by circulating enzymes.

Inside the cell, many different enzymes reverse the cellular modifications resulting from signalling cascades. For example, phosphatases are enzymes that remove the phosphate group attached to proteins by kinases in a process called dephosphorylation. cAMP is degraded into AMP by phosphodiesterase, and the Ca2+ pumps located in the external and internal membranes of the cell reverse the release of calcium stores.

Learning Activity: Variety of Cellular Responses

- Watch the following videos:

- “Cell Communication 4 Cellular Response” (13:41 min) by Bialecki Biology (2021).

- “Activation and inhibition of signal transduction pathways | AP Biology | Khan Academy” (5:56 min) by Khan Academy (2018).

- Answer the following questions:

- What are the two major cellular responses to signal transduction?

- What does glycogen phosphorylase do?

- What are the different responses a cell can make to a signalling molecule?

- How does cholera toxin affect G-protein signalling?

- How are signals terminated?

- Why would you want more enkephalin if you had cholera?

Key Concepts and Summary

While all somatic cells within an organism contain the same DNA, not all cells within that organism express the same proteins. Cells express proteins only when they are needed. Eukaryotic organisms express a subset of the DNA encoded in any given cell. In each cell type, controlling gene expression regulates the type and amount of protein. Expressing a protein first involves transcribing DNA into RNA, which then translates into proteins. In eukaryotic cells, transcription occurs in the nucleus and is separate from the translation occurring in the cytoplasm. In eukaryotic cells, cells regulate gene expression at the epigenetic, transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. Transcription factors (acting as activators or repressors) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) control differential gene regulation in eukaryotes.

Ligand binding to the receptor allows for signal transduction through the cell. The chain of events that conveys the signal through the cell is called a signalling pathway or cascade. Signalling pathways are often very complex because of the interplay between different proteins. A major component of cell signalling cascades is the phosphorylation of molecules by enzymes known as kinases. Phosphorylation adds a phosphate group to serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues in a protein, changing their shapes and activating or inactivating the protein. Small molecules, like nucleotides, can also be phosphorylated. Second messengers are small non-protein molecules a cell can use to transmit a signal within itself. Some examples of second messengers are calcium ions (Ca2+), cyclic AMP (cAMP), diacylglycerol (DAG), and inositol triphosphate (IP3).

The initiation of a signalling pathway is a response to external stimuli. This response can take many different forms, including protein synthesis, a change in the cell’s metabolism, cell growth, or even cell death. Many pathways influence the cell by initiating gene expression, and the methods utilized are quite numerous. Some pathways activate enzymes that interact with DNA transcription factors. Others modify proteins and induce them to change their location in the cell. Depending on the status of the organism, cells can respond by storing energy as glycogen or fat or making it available in the form of glucose. A signal transduction pathway allows muscle cells to respond to immediate requirements for energy in the form of glucose.

Cell growth almost always occurs from stimulation by external signals called growth factors. Uncontrolled cell growth leads to cancer, and tumour cells often have mutations in the genes encoding protein components of signalling pathways. Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is important for removing damaged or unnecessary cells.

- Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death, or “cellular suicide.” It is different from necrosis, in which cells die due to injury.

- Apoptosis is an orderly process in which the cell’s contents are packaged into small packets of membrane (bleb) for “garbage collection” by immune cells.

- Apoptosis removes cells during development, eliminates potentially cancerous and virus-infected cells, and maintains balance in the body.

Using cellular signalling to organize the dismantling of a cell ensures that harmful molecules from the cytoplasm are not released into the spaces between cells, as they are in uncontrolled death (necrosis). Apoptosis also ensures the efficient recycling of the components of the dead cell. Termination of the cellular signalling cascade is very important so that the response to a signal is appropriate in both timing and intensity. Degradation of signalling molecules and dephosphorylation of phosphorylated intermediates of the pathway by phosphatases are two ways to terminate signals within the cell.

Key Terms

activator

protein that binds to DNA to increase transcription

apoptosis

programmed cell death

cyclic AMP (cAMP)

second messenger that is derived from ATP

cyclic AMP-dependent kinase (also protein kinase A or PKA)

kinase that is activated by binding to cAMP

diacylglycerol (DAG)

cleavage product of PIP2 that is used for signalling within the plasma membrane

dimer

chemical compound formed when two molecules join together

dimerization

(of receptor proteins) interaction of two receptor proteins to form a functional complex called a dimer

enhancer

segment of DNA that is upstream, downstream, perhaps thousands of nucleotides away, or on another chromosome that influence the transcription of a specific gene

eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF-2)

protein that binds first to an mRNA to initiate translation

gene expression

processes that control the turning on or turning off of a gene

growth factor

ligand that binds to cell-surface receptors and stimulates cell growth

inositol phospholipid

lipid present at small concentrations in the plasma membrane that is converted into a second messenger; it has inositol (a carbohydrate) as its hydrophilic head group

inositol triphosphate (IP3)

cleavage product of PIP2 that is used for signalling within the cell

kinase

enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to another molecule

negative regulator

protein that prevents transcription

phosphatase

enzyme that removes the phosphate group from a molecule that has been previously phosphorylated

phosphodiesterase

enzyme that degrades cAMP, producing AMP, to terminate signalling

positive regulator

protein that increases transcription

second messenger

small, non-protein molecule that propagates a signal within the cell after activation of a receptor causes its release

signal integration

interaction of signals from two or more different cell-surface receptors that merge to activate the same response in the cell

signal transduction

propagation of the signal through the cytoplasm (and sometimes also the nucleus) of the cell

signalling pathway (also signalling cascade)

chain of events that occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell to propagate the signal from the plasma membrane to produce a response

transcription factor binding site

sequence of DNA to which a transcription factor binds

transcriptional start site

the location where the first DNA nucleotide at the 5’ end of a gene sequence is transcribed into RNA

Long Descriptions

Figure 2 Image Description: The signal transduction pathway goes as follows:

- The pathway is off because no ligand is present.

- A ligand binds to the receptor and activates it.

- The receptor activates a protein at the membrane.

- The protein at the membrane activates a protein in the cytosol.

- The protein in the cytosol activates the final target of pathway.

- The final target protein causes a response. [Return to Figure 2]

Figure 6 Image Description: Upon binding epidermal growth factor (EGF) to the EGF receptor (EGFR), two proteins associated with the receptor called GRB2 and SOS activate RAS, a small G-protein.

RAS-GTP activates a protein kinase called RAF. RAF phosphorylates MEK, which in turn phosphorylates ERK, a MAP kinase. The phosphorylated ERK enters the nucleus, where it triggers a cellular response. This response stimulates cell proliferation, cell migration and adhesion, and angiogenesis (growth of new blood vessels). It also inhibits apoptosis. [Return to Figure 6]

Figure 21 Image Description: Growth factor binding to a growth factor receptor activates a phosphorylation cascade. For transcription, c-Myc in the nucleus activates and transcribes genes that promote cell growth and division. mRNA takes this transcription out of the nucleus to where protein production occurs. For translation, MNKI in the cytoplasm activates and increases the translation of certain mRNAs that move onto where protein production occurs. Both transcription and translation processes result in cell growth and division. [Return to Figure 21]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Introduction by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Binding initiates a signaling pathway by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Phosphorylation [Image 1] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 9.11 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Phosphorylation [Image 2] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 9.10 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 9.12 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Cyclic AMP (cAMP) by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 9.13 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Inositol phosphates by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: And…it’s even more complicated than that! [Image 1] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: And…it’s even more complicated than that! [Image 2] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Gene regulation makes cells different by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: How do cells “decide” which… by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Transcription factors by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 16: Activators by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 17: Repressors by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 18: Binding sites by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 19: Gene Expression Essentials [Screenshot, gene transcription simulation] by PhET (2019) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 20: Gene Expression Essentials [Screenshot 2, protein level simulation] by PhET (2019) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- Figure 21: Example: Growth factor signaling by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 22: Figure 9.14 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 23: Cellular Metabolism by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 24: Figure 15.6 by Kindred Grey from Cell Biology, Genetics, and Biochemistry for Pre-Clinical Students (LeClair 2021) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 25: Figure 9.15 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

Bialecki Biology. Cell communication 4 cellular response [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Apr 25, 13:41 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFIzEvF_ETQ.

Bozeman Science. Signal transduction pathways [Video]. YouTube. 2011 Aug 21, 9:24 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOVkedxDqQo.

DNA Learning Center. Cell signals [Video]. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: DNA Learning Center. 2010 Mar 19, 14:15 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://dnalc.cshl.edu/resources/3d/cellsignals.html.

Elvire Thouvenot-Nitzan. “What is apoptosis?” the apoptotic pathways and the caspase cascade [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Oct 18, 3:58 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vmtK-bAC5E.

5 Hay N. 2010. Mnk earmarks eIF4E for cancer therapy. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 107(32):13975-13976. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1008908107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008908107.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 15: cell death and cancer. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/db353ee7-8050-4d91-b3e7-2ed8ce59e5e7.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Overview: eukaryotic gene regulation. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures gene regulation makes cells different, how do cells “decide” which…. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/gene-expression-and-regulation/regulation-of-gene-expression-and-cell-specialization/a/overview-of-eukaryotic-gene-regulation.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Response to a signal. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures example: growth factor signaling, cellular metabolism. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-communication-and-cell-cycle/signal-transduction/a/cellular-response.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Signal relay pathways. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures introduction, binding initiates a signaling pathway, phosphorylation [Image 1, 2], cyclic AMP (cAMP), inositol phosphates, And…it’s even more complicated than that! [image 1, 2]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/cell-signaling/mechanisms-of-cell-signaling/a/intracellular-signal-transduction.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Transcription factors. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures transcription factors, activators, repressors, binding sites. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/gene-expression-and-regulation/regulation-of-gene-expression-and-cell-specialization/a/eukaryotic-transcription-factors.

Khan Academy. DNA replication and RNA transcription and translation [Video]. Khan Academy. 2014 Dec 10, 15:23 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/macromolecules/nucleic-acids/v/rna-transcription-and-translation.

Khan Academy. Apoptosis | cell division | biology | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Aug 10, 10:47 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNFDONSjB7Q.

Khan Academy. Activation and inhibition of signal transduction pathways | AP biology | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Oct 31, 5:55 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zYX5a65LrXs.

Khanacademymedicine. Cellular mechanism of hormone action | endocrine system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Sep 18, 8:22 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNGSzt2v4xY.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 15.2: apoptosis. Figure 15.6. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students/15%3A_Cellular_Signaling/15.02%3A_Apoptosis.

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax).

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 16.4: eukaryotic transcription gene regulation. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax)/3%3A_Genetics/16%3A_Gene_Expression/16.4%3A_Eukaryotic_Transcription_Gene_Regulation.

PhET. 2019. Gene expression essentials [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:8ccf7483:lx_simulation:1.

2 R&D Systems. [date unknown]. The ERK signal transduction pathway. Minneapolis (MN): R&D Systems, Inc. https://www.rndsystems.com/resources/articles/erk-signal-transduction-pathway.

1 Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB. 2019. Campbell biology. 10th ed. London (England): Pearson. Cell Communication; p. 223, 228.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 16.4: eukaryotic transcription gene regulation. Figures 9.10 to 9.15. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

7 Sonnenfeld MJ, Jacobs JR. 1995. Apoptosis of the midline glia during Drosophila embryogenesis: a correlation with axon contact. Development. 121(2):569-578. https://journals.biologists.com/dev/article/121/2/569/38762/Apoptosis-of-the-midline-glia-during-Drosophila. doi:10.1242/dev.121.2.569.

6 Steller H. 1995. Mechanisms and genes of cellular suicide. Science. 267(5203):1445-1449. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.7878463. doi:10.1126/science.7878463.

4 Wendel H-G, Silva RLA, Malina A, Mills JR, Zhu H, Ueda T, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Fukunaga R, Teruya-Feldstein, J, Pelletier J, et al. 2007. Dissecting eIF4E action in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 21:3232-3237. https://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/21/24/3232. doi:10.1101/gad.1604407.

3 Wikipedia Contributors. 2015. Myc. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2015 Oct 8; accessed 2015 Nov 5]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Myc&oldid=684757177.

Yang J-L J, Bertolesi GE, Dueck S, Hehr CL, McFarlane S. 2019. The expression of key guidance genes at a forebrain axon turning point is maintained by distinct fgfr isoforms but a common downstream signal transduction mechanism. eNeuro. 6(2):1-19. https://www.eneuro.org/content/6/2/ENEURO.0086-19.2019. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0086-19.2019.

chain of events that occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell to propagate the signal from the plasma membrane to produce a response

propagation of the signal through the cytoplasm (and sometimes also the nucleus) of the cell

enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to another molecule

enzyme that removes the phosphate group from a molecule that has been previously phosphorylated

ligand that binds to cell-surface receptors and stimulates cell growth

(of receptor proteins) interaction of two receptor proteins to form a functional complex called a dimer

chemical compound formed when two molecules join together

small, non-protein molecule that propagates a signal within the cell after activation of a receptor causes its release

second messenger that is derived from ATP

lipid present at small concentrations in the plasma membrane that is converted into a second messenger; it has inositol (a carbohydrate) as its hydrophilic head group

kinase that is activated by binding to cAMP

cleavage product of PIP2 that is used for signalling within the plasma membrane

cleavage product of PIP2 that is used for signalling within the cell

interaction of signals from two or more different cell-surface receptors that merge to activate the same response in the cell

processes that control the turning on or turning off of a gene

protein that binds to DNA to increase transcription

sequence of DNA to which a transcription factor binds

segment of DNA that is upstream, downstream, perhaps thousands of nucleotides away, or on another chromosome that influence the transcription of a specific gene

protein that increases transcription

protein that prevents transcription

programmed cell death

enzyme that degrades cAMP, producing AMP, to terminate signalling