4.3 The Cell Cycle and its Regulation

Introduction

Have you ever watched a caterpillar turn into a butterfly? If so, you are probably familiar with the idea of a life cycle. Butterflies go through some spectacular life cycle transitions — turning from something that looks like a worm into a pupa and finally into a glorious creature that floats on the breeze. Other organisms, from humans to plants to bacteria, also have a life cycle, which is a series of developmental steps that an individual goes through from the time it is born until the time it reproduces.

The continuity of life from one cell to another has its foundation in the reproduction of cells by way of the cell cycle. The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events that describes the stages of a cell’s life, from the division of a single parent cell to the production of two new genetically identical daughter cells.

Unit 4, Topic 3 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 4, Topic 3, you will be able to:

- Describe the three stages of interphase.

- Discuss the behaviour of chromosomes during karyokinesis/mitosis.

- Explain how the cytoplasmic content is divided during cytokinesis.

- Define the quiescent G0 phase.

- Explain how the cell cycle is controlled by mechanisms that are both internal and external to the cell.

- Explain how the three internal “control checkpoints” occur at the end of G1, at the G2/M transition, and during metaphase.

- Describe the molecules that control the cell cycle through positive and negative regulation.

| Unit 4, Topic 3—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions from Unit 4, Topic 3 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell cycle variability. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell cycle controls and cancer. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: The cell cycle control system. | 40 |

Stages of the Cell Cycle

A cell must complete several important tasks to divide: grow, copy its genetic material (DNA), and physically split into two daughter cells. Cells perform these tasks in an organized, predictable series of steps that make up the cell cycle. The cell cycle is a cycle rather than a linear pathway because at the end of each go-round, the two daughter cells can start the exact same process over again from the beginning.

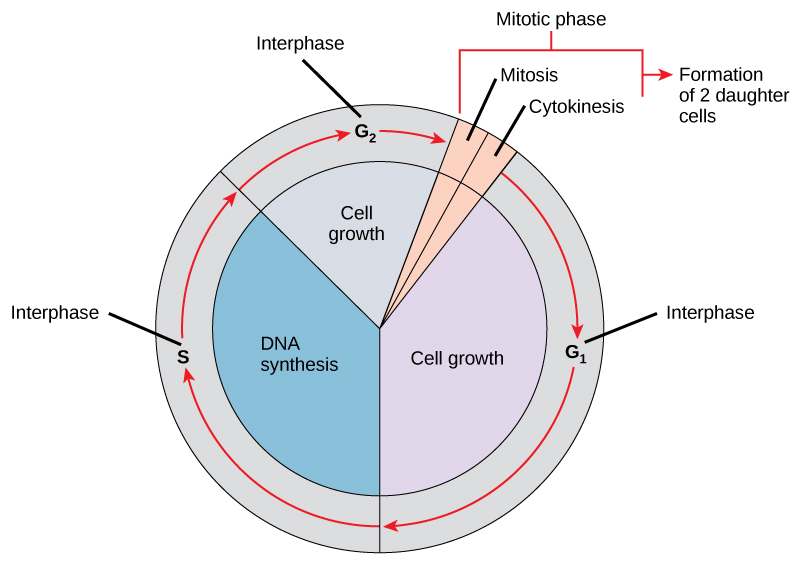

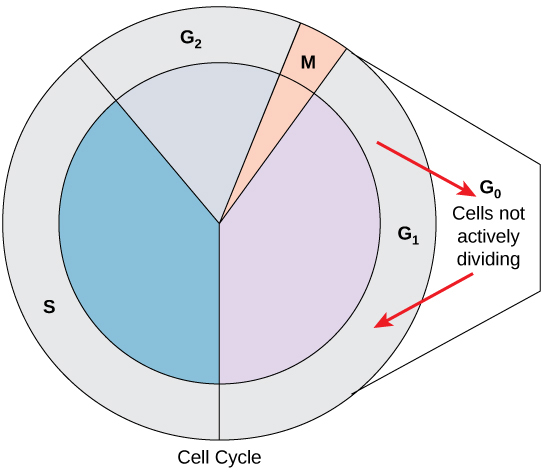

In eukaryotic cells or cells with a nucleus, the stages of the cell cycle are part of one of two main phases: interphase and the mitotic (M) phase (Figure 1).

- During interphase, the cell grows and makes a copy of its DNA.

- During the mitotic (M) phase, the cell separates its DNA into two sets and divides its cytoplasm during cytokinesis to form two new cells.

However, note that interphase and mitosis (karyokinesis) may take place without cytokinesis, such as producing cells with multiple nuclei (multinucleate cells).

Interphase

During interphase, the cell undergoes normal growth processes while also preparing for cell division. A cell must meet many internal and external conditions to move from the interphase into the mitotic phase. The three stages of interphase are called G1, S, and G2.

G1 Phase (First Gap)

The first interphase stage is known as the G1 phase (first gap) because little change is visible from a microscopic point of view. However, during the G1 stage, the cell is quite active at the biochemical level. The cell accumulates the building blocks of chromosomal DNA and the associated proteins and sufficient energy reserves to complete the replication of each chromosome in the nucleus. Furthermore, during the G1 stage, DNA is assessed for damage and repaired, if needed, and the cell also grows in size.

S Phase (Synthesis of DNA)

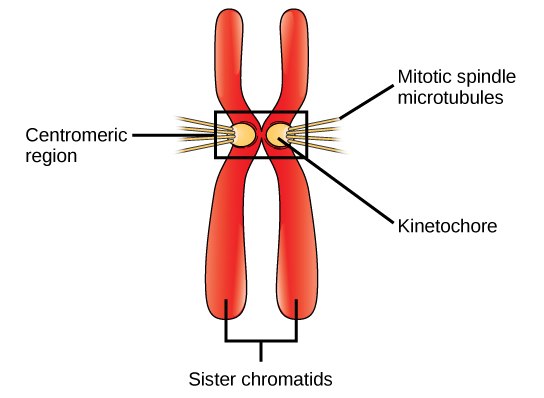

Throughout interphase, nuclear DNA remains in a semi-condensed chromatin configuration. In the S phase, DNA replication can proceed through the mechanisms resulting in identical pairs of DNA molecules forming — sister chromatids — that firmly attach to the centromeric region. Proteins called cohesins loop around sister chromatids to keep them connected. The centrosome also duplicates during the S phase. Each centrosome of an animal cell consists of two centrioles that give rise to the mitotic spindle, the apparatus that orchestrates how chromosomes move during mitosis. Roughly at the centre of each animal cell are the rod-like pair of centrioles positioned at right angles to each other. However, note that centrioles are not in the centrosomes of other eukaryotic organisms, such as plants and most fungi.

G2 Phase (Second Gap)

In the G2 phase, the cell replenishes its energy stores and synthesizes proteins necessary for chromosome manipulation and movement. This phase duplicates some cell organelles and dismantles the cytoskeleton to provide resources for the mitotic phase. Additional cell growth may occur during G2. The cell must complete the final preparations for the mitotic phase before it can enter the first stage of mitosis.

Self-Check

Briefly describe the events that occur in each subphase of interphase.

Show/Hide answer.

During G1, the cell increases in size, assesses the genomic DNA for damage, and stockpiles energy reserves and the components to synthesize DNA. During the S phase, the chromosomes, the centrosomes, and the centrioles (animal cells) duplicate. During the G2 phase, the cell recovers from the S phase, continues to grow, duplicates some organelles, and dismantles other organelles.

The Mitotic Phase

The mitotic phase is a multistep process involving duplicated chromosomes aligning, separating, and moving into two new, identical daughter cells. The first portion of the mitotic phase is karyokinesis (nuclear division). The second portion of the mitotic phase (often viewed as a process separate from and following mitosis) is called cytokinesis — the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into the two daughter cells.

Karyokinesis (Mitosis)

Karyokinesis, also known as mitosis, is divided into a series of phases — prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase — that result in the division of the cell nucleus (Figure 2). Note that this is a continuous process, and the divisions between stages are not discrete.

Prophase (The “First Phase”)

During prophase, the “first phase,” several events must occur to provide access to the chromosomes in the nucleus. The nuclear envelope starts to dissociate into small vesicles, caused by phosphorylation of nuclear pore proteins and lamins (intermediate filament cytoskeletal proteins that provide structure to the nuclear envelope (see Unit 3, Topic 4)) by the cell cycle regulatory protein M-cyclin/Cdk. Later in telophase, these proteins will dephosphorylate to reform the nuclear envelope.

Additionally, the membranous organelles (e.g., the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum) fragment and disperse toward the periphery of the cell. The nucleolus disappears (disperses), and the centrosomes begin moving to opposite poles in the cell. The microtubules that form the mitotic spindle extend between the centrosomes, pushing them farther apart as the microtubule fibres lengthen due to dynamic instability (see Unit 3, Topic 4). The sister chromatids begin coiling more tightly and become visible under a light microscope. Facilitating this process is done by proteins called condensins, ring-shaped proteins that further condense chromatin. M-cyclin/Cdk phosphorylates Condensins to allow further condensation of chromatin.

Prometaphase (The “First Change Phase”)

Many processes that began in prophase continue to advance. The remnants of the nuclear envelope fragment further, and the mitotic spindle continues to develop as more microtubules assemble and stretch across the length of the former nuclear area. Chromosomes become even more condensed and discrete. Each sister chromatid develops a protein structure called a kinetochore in its centromeric region (Figure 3). The proteins of the kinetochore attract and bind to the mitotic spindle microtubules. As the spindle microtubules extend from the centrosomes, some of these microtubules meet and firmly bind to the kinetochores. Once a mitotic fibre attaches to a chromosome, the chromosome orients until the kinetochores of sister chromatids face the opposite poles. Eventually, all the sister chromatids attach via their kinetochores to microtubules from opposing poles. Spindle microtubules that do not engage the chromosomes are called polar microtubules. These microtubules overlap each other midway between the two poles and contribute to cell elongation. Astral microtubules are located near the poles, aid in spindle orientation, and are required for regulating mitosis.

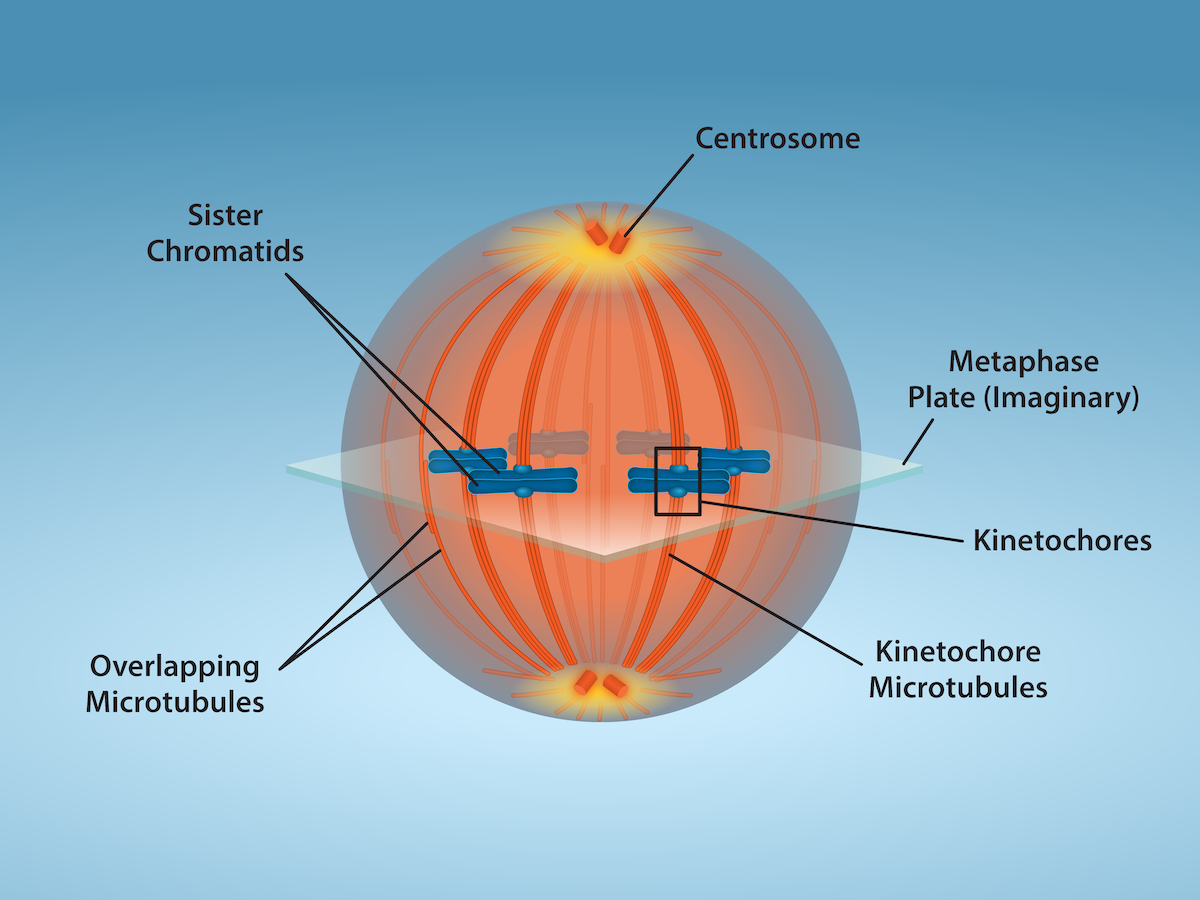

Metaphase (The “Change Phase”)

All the chromosomes are aligned in a plane called the metaphase plate, or the equatorial plane, roughly midway between the two poles of the cell (Figure 4). The sister chromatids are still tightly attached to each other by cohesin proteins. At this time, the chromosomes are maximally condensed.

Anaphase (“Upward Phase”)

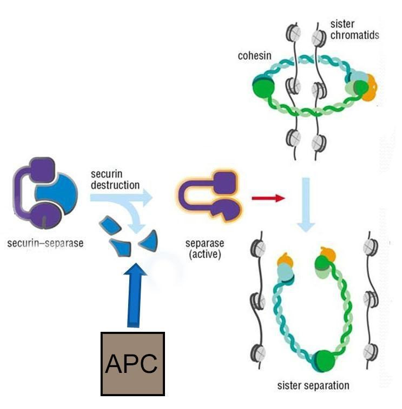

During anaphase, cohesions hold the sister chromatids together at the equatorial plane. Before the chromatids can be separated, the cohesins must be removed. A protein called an anaphase promoting complex (APC) regulates this process. Prior to anaphase, APC is in its inactive (dephosphorylated) state. At the beginning of anaphase, M-cyclin/Cdk phosphorylates APC and becomes active. APC is a ubiquitin ligase, meaning it can add a small peptide called ubiquitin to proteins. When ubiquitin ligases add certain polymers of ubiquitin to proteins (called polyubiquitination), it “tags” the proteins for degradation by the proteasome. At the beginning of anaphase, APC polyubiquitinates the protein securin, causing the proteasome to degrade the securin. The degradation of securin releases the protein separase. Separase is the enzyme that physically breaks down the cohesin proteins that hold the sister chromatids together (Figure 5).

After cohesion removal, each sister chromatid, now called a chromosome, is pulled rapidly toward the centrosome to which its microtubule was attached. The cell becomes visibly elongated as the non-kinetochore microtubules slide against each other at the metaphase plate, where they overlap.

Telophase (The “Distance Phase”)

During telephase, the chromosomes reach the opposite poles and begin to decondense (unravel), relaxing once again into a stretched-out chromatin configuration. Mitotic spindles depolymerize into tubulin monomers used to assemble cytoskeletal components for each daughter cell. Nuclear envelopes form around the chromosomes, and nucleosomes appear within the nuclear area.

Self-Check

- Chemotherapy drugs such as vincristine (derived from Madagascar periwinkle plants) and colchicine (derived from autumn crocus plants) disrupt mitosis by binding to tubulin (a subunit of microtubules) and interfering with microtubule assembly and disassembly. Exactly what mitotic structure do these drugs target, and what effect would that have on cell division?

Show/Hide answer.

The mitotic spindle consists of microtubules. Microtubules are polymers of the protein tubulin; therefore, it is the mitotic spindle that these drugs disrupt. Without a functional mitotic spindle, the chromosomes will not be sorted or separated during mitosis. The cell will arrest in mitosis and die.

- What cell cycle events will be affected in a cell that produces mutated (non-functional) cohesin protein?

Show/Hide answer.

If cohesin is not functional, chromosomes remain unpackaged after DNA replication in the S phase of interphase. It is likely that the proteins of the centromeric region, such as the kinetochore, would not form. Even if the mitotic spindle fibres could attach to the chromatids without packing, the chromosomes would not be sorted or separated during mitosis.

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis, or “cell motion,” is sometimes viewed as the second main stage of the mitotic phase, during which cell division completes after the cytoplasmic components physically separate into two daughter cells. As seen earlier, however, cytokinesis can also be viewed as a separate phase, which may or may not take place following mitosis. If cytokinesis does take place, cell division is not complete until the cell components have been apportioned and completely separated into the two daughter cells. Although the stages of mitosis are similar for most eukaryotes, the process of cytokinesis is quite different for eukaryotes with cell walls, such as plant cells.

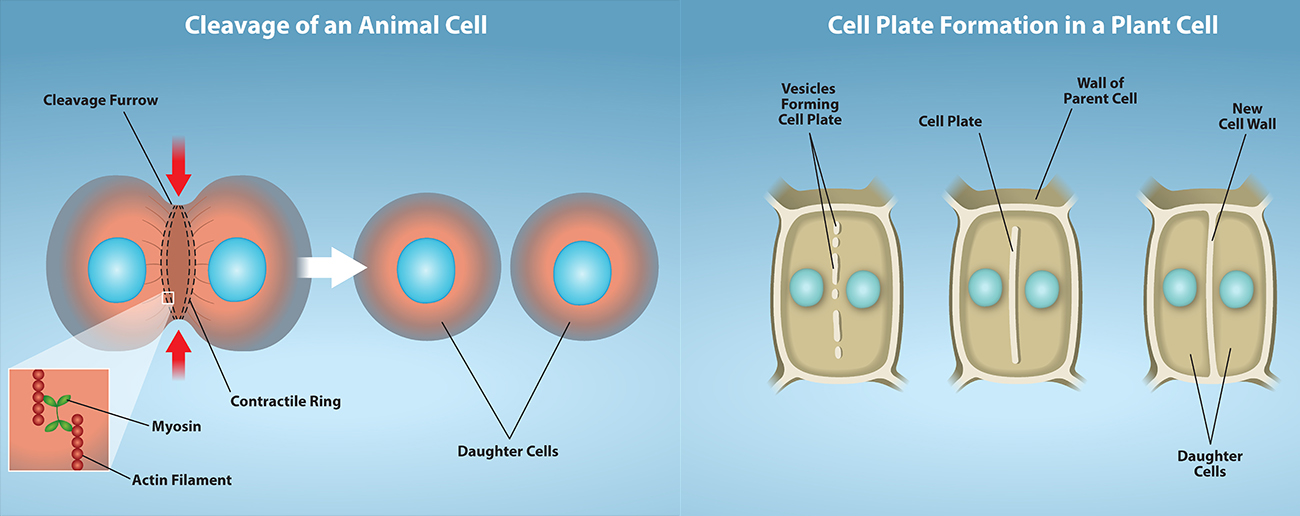

In animal cells, cytokinesis typically starts during late anaphase. Cytokinesis involves a contractile ring of actin filaments and myosin II bundles forming just inside the plasma membrane at the former metaphase plate. The actin filaments pull the equator of the cell inward, forming a fissure. This fissure is called the cleavage furrow. The furrow deepens as the actin ring contracts, and eventually, the membrane is cleaved in two (Figure 6, Left).

Plant cells must form a new cell wall between the daughter cells. During interphase, the Golgi apparatus accumulates enzymes, structural proteins, and glucose molecules prior to breaking into vesicles and dispersing throughout the dividing cell. During telophase, these Golgi vesicles are transported on microtubules to form a phragmoplast (a vesicular structure) at the metaphase plate. Once there, the vesicles fuse and coalesce from the centre toward the cell walls; this structure is called a cell plate. As more vesicles fuse, the cell plate enlarges until it merges with the cell walls at the periphery of the cell. Enzymes polymerize the accumulated glucose between the membrane layers to build a new cell wall of cellulose. The Golgi membranes become parts of the plasma membrane on either side of the new cell wall (Figure 6, Right).

Self-Check

Describe the similarities and differences between the cytokinesis mechanisms found in animal cells versus plant cells.

Show/Hide answer.

There are very few similarities between animal cell and plant cell cytokinesis.

In animal cells, a ring of actin fibres is formed around the periphery of the cell at the former metaphase plate (cleavage furrow). The actin ring contracts inward, pulling the plasma membrane toward the centre of the cell until it pinches the cell in two.

Plant cells must form a new cell wall between the daughter cells. The rigid cell walls of the parent cell make it impossible to contract the middle of the cell; instead, a phragmoplast forms first. A cell plate subsequently forms in the centre of the cell at the former metaphase plate. The cell plate is formed from Golgi vesicles that contain enzymes, proteins, and glucose. The vesicles fuse, and the enzymes build a new cell wall from the proteins and glucose. The cell plate grows toward and eventually fuses with the cell wall of the parent cell.

G0 Phase

Not all cells adhere to the classic cell cycle pattern in which a newly formed daughter cell immediately enters the preparatory phases of interphase, closely followed by the mitotic phase and cytokinesis. Cells in G0 phase are not actively preparing to divide. The cell is in the quiescent (inactive) stage that occurs when cells exit the cell cycle. Some cells enter G0 temporarily due to environmental conditions, such as the availability of nutrients or stimulation by growth factors. The cell remains in this phase until conditions improve or until an external signal triggers the onset of G1. Other cells that never or rarely divide, such as mature cardiac muscle and nerve cells, remain in G0 permanently (Figure 7).

Self-Check

List some reasons why a cell that has just completed cytokinesis might enter the G0 phase instead of the G1 phase.

Show/Hide answer.

Many cells temporarily enter G0 until they reach maturity. Some cells are only triggered to enter G1 when the organism needs to increase that particular cell type. Some cells only reproduce following an injury to the tissue. Some cells never divide once they reach maturity.

Control of the Cell Cycle

The length of the cell cycle is highly variable, even within the cells of a single organism. In humans, the frequency of cell turnover ranges from a few hours in early embryonic development to an average of two to five days for epithelial cells to an entire human lifetime spent in G0 by specialized cells, such as cortical neurons or cardiac muscle cells.

There is also variation in the time a cell spends in each cell cycle phase. When rapidly dividing mammalian cells are grown in a culture (outside the body under optimal growing conditions), the cell cycle length is about 24 hours. In rapidly dividing human cells with a 24-hour cell cycle, the G1 phase lasts approximately nine hours, the S phase lasts 10 hours, the G2 phase lasts about four and a half hours, and the M phase lasts about half an hour. By comparison, in fertilized eggs (and early embryos) of fruit flies, the cell cycle is completed in about eight minutes. This is because the nucleus of the fertilized egg divides many times by mitosis but does not go through cytokinesis until a multinucleate “zygote” has been produced, with many nuclei located along the periphery of the cell membrane, thereby shortening the time of the cell division cycle. The timing of events in the cell cycle of both “invertebrates” and “vertebrates” is controlled by mechanisms that are both internal and external to the cell.

Learning Activity: Cell Cycle Variability

- Watch the following videos:

- “Early mitotic divisions in a Drosophila embryo” (30 s) by Tglab (2008).

- “Mitosis in Drosophila embryo” (1:35 min) by Mr. Riddz Science (2016).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is unique about early Drosophila nuclear divisions compared to those of vertebrates?

- What components of the cells in Mr. Riddz’s video were labelled, and how were they visualized?

Regulation of the Cell Cycle by External Events

Both the initiation and inhibition of cell division are triggered by events external to the cell when it is about to begin the replication process. An event may be as simple as the death of nearby cells or as sweeping as the release of growth-promoting hormones, such as human growth hormone (HGH). A lack of HGH can inhibit cell division, resulting in dwarfism, whereas too much HGH can result in gigantism. Crowding of cells can also inhibit cell division. In contrast, a factor that can initiate cell division is the cell size; as a cell grows, it becomes physiologically inefficient due to its decreasing surface-to-volume ratio. The solution to this problem is to divide.

Whatever the source of the message, the cell receives the signal, and a series of events within the cell allows it to proceed into interphase. After this initiation point, the cell must meet every required parameter in each cell cycle phase, or the cycle cannot progress.

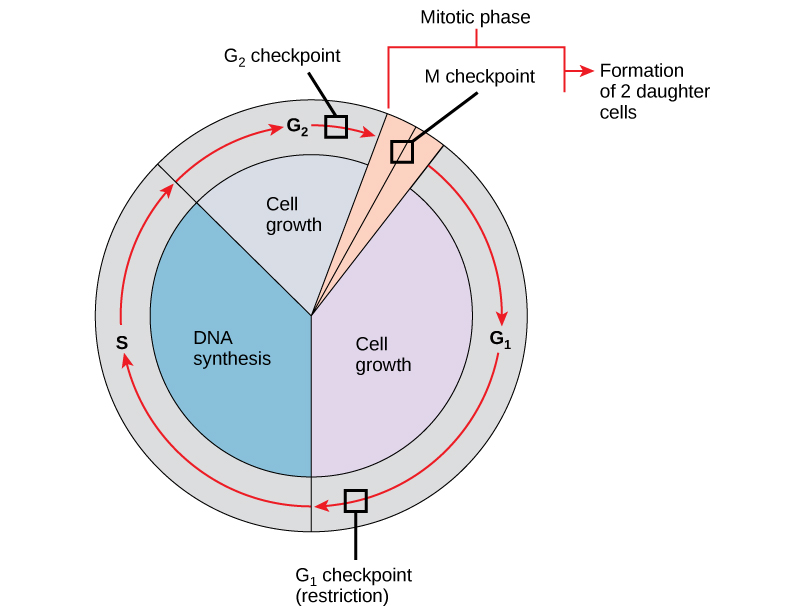

Regulation at Internal Checkpoints

A parent cell must produce daughter cells that are exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may pass onto every new cell produced from an abnormal cell. Preventing a compromised cell from continuing to divide involves internal control mechanisms operating at three main cell cycle checkpoints. A checkpoint is one of several points in the eukaryotic cell cycle that can stop the progression of a cell to the next stage in the cycle until conditions are favourable. These checkpoints occur near the end of G1, at the G2/M transition, and during metaphase (Figure 8).

The G1 Checkpoint

The G1 checkpoint determines whether all conditions are favourable for cell division to proceed. The G1 checkpoint, also called the restriction point (in yeast), is a point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell division process. External influences, such as growth factors, play a large role in carrying the cell past the G1 checkpoint. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for genomic DNA damage at the G1 checkpoint. A cell that does not meet all the requirements cannot progress into the S phase. The cell can halt the cycle and attempt to remedy the problematic condition, or the cell can advance into G0 and await further signals when conditions improve.

The G2 Checkpoint

The G2 checkpoint bars entry into the mitotic phase if the cell does not meet certain conditions. As at the G1 checkpoint, the G2 checkpoint addresses cell size and protein reserves. However, the most important role of the G2 checkpoint is to ensure that all chromosomes have replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged. If the checkpoint mechanisms detect problems with the DNA, the cell cycle halts, and the cell attempts to either complete DNA replication or repair the damaged DNA.

The M Checkpoint

The M checkpoint occurs near the end of the metaphase stage of karyokinesis. The M checkpoint is also known as the spindle checkpoint because it determines whether all the sister chromatids are correctly attached to the spindle microtubules. Because separating the sister chromatids during anaphase is an irreversible step, the cycle will not proceed until the kinetochores of each pair of sister chromatids firmly anchor to at least two spindle fibres arising from opposite poles of the cell.

Self-Check

Describe the general conditions that must be met at each of the three main cell cycle checkpoints.

Show/Hide answer.

The G1 checkpoint monitors adequate cell growth, the state of the genomic DNA, adequate stores of energy, and materials for the S phase.

The G2 checkpoint checks DNA to ensure that all chromosomes are duplicated and that there are no mistakes in newly synthesized DNA. Additionally, cell size and energy reserves are evaluated.

The M checkpoint confirms the correct attachment of the mitotic spindle fibres to the kinetochores.

Regulator Molecules of the Cell Cycle

The discussion above looked at the why of cell cycle transitions: the factors that a cell considers when deciding whether to move forward through the cell cycle. These include both external cues (e.g., molecular signals) and internal cues (e.g., DNA damage). Such cues change the activity of core cell cycle regulators inside the cell. These core cell cycle regulators can cause key events, such as DNA replication or chromosome separation, to take place. They also ensure that cell cycle events happen in the correct order and that one phase (e.g., G1) triggers the onset of the next phase (e.g., S).

In addition to the internally controlled checkpoints, two groups of intracellular molecules also regulate the cell cycle. These regulatory molecules either promote the progress of the cell to the next phase (positive regulation) or halt the cycle (negative regulation). Regulator molecules may act individually or influence the activity or production of other regulatory proteins. Therefore, the failure of a single regulator may have almost no effect on the cell cycle, especially if more than one mechanism controls the same event. However, the effect of a deficient or non-functioning regulator can be wide-ranging and possibly fatal to the cell if multiple processes are affected.

Positive Regulation of the Cell Cycle

This section looks at two important core cell-cycle regulators: proteins called cyclins and enzymes called Cdks.

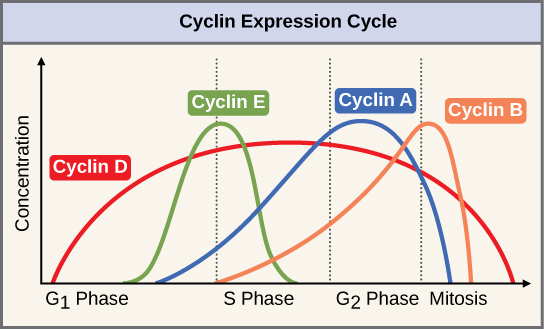

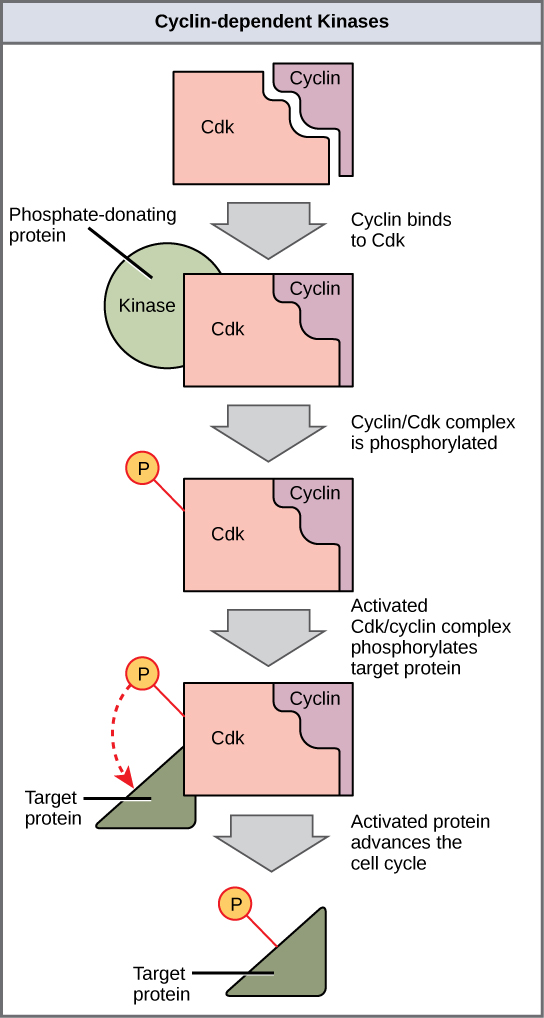

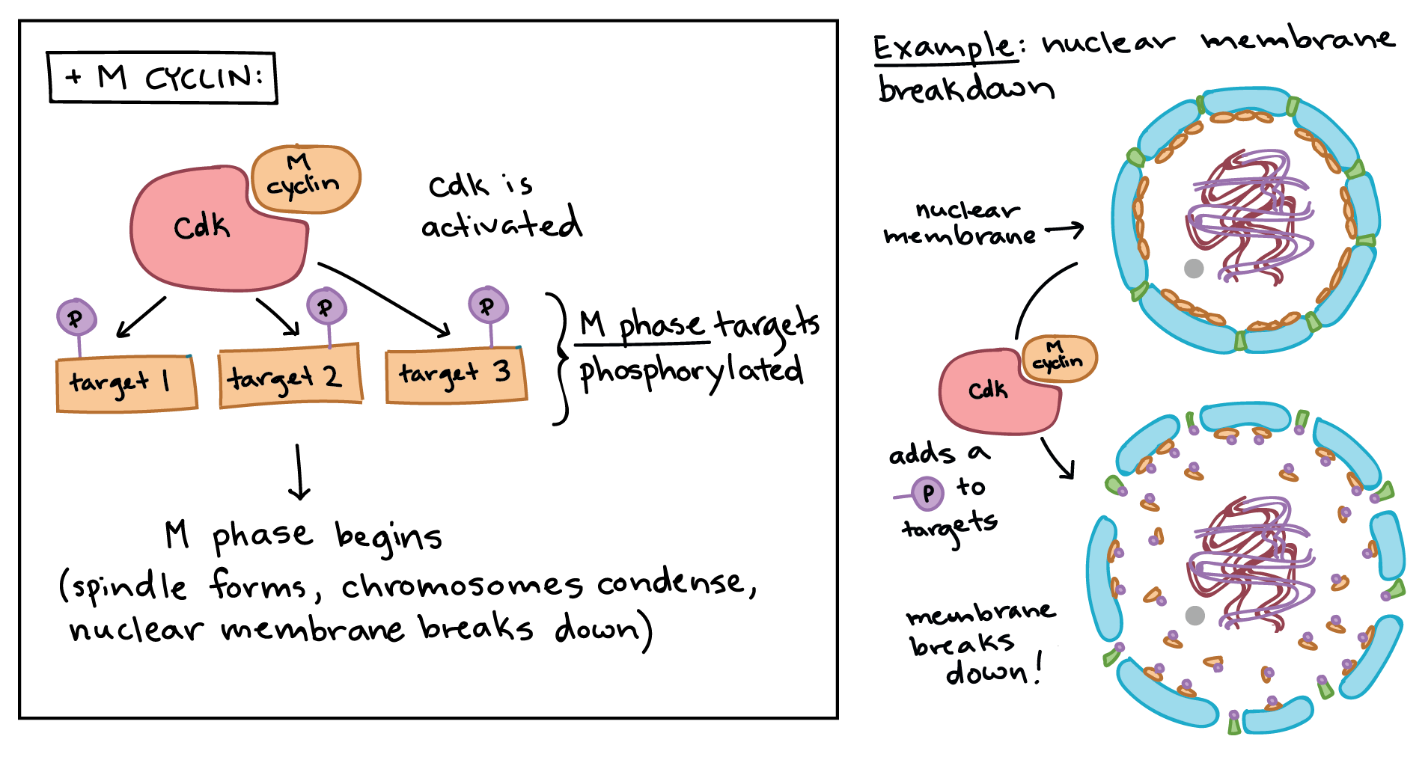

Two groups of proteins, cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), are termed positive regulators. They are responsible for the progress of the cell through the various checkpoints. Cyclins are among the most important core cell cycle regulators. Cyclins are a group of related proteins, and there are four basic types found in humans and most other eukaryotes: G1 cyclins, G1/S cyclins, S cyclins, and M cyclins. As the names suggest, each cyclin is associated with a particular phase, transition, or set of phases in the cell cycle and helps drive the events of that phase or period. For instance, M cyclin promotes the events of the M phase, such as nuclear envelope breakdown and chromosome condensation.1,2 The levels of the four cyclin proteins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle in a predictable pattern (Figure 9). External and internal signals trigger increases in cyclin protein concentrations. After the cell moves to the next stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins active in the previous stage are degraded by cytoplasmic enzymes, as shown in Figure 9 by their drastic drop in concentration.

A lone Cdk is inactive, but the binding of a cyclin activates it, making it a functional enzyme and allowing it to modify target proteins. Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound to Cdks. To fully activate, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be phosphorylated in specific locations to activate the complex; it may also be negatively regulated by phosphorylation of other sites.3,4 Like all kinases, Cdks are enzymes that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by Cdks help advance the cell to the next phase (Figure 10). The levels of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle; however, the cyclin concentrations fluctuate and determine when Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks bind at specific points in the cell cycle, thus regulating different checkpoints. For example, G1/S cyclins send Cdks to S-phase targets (e.g., promoting DNA replication), while M cyclins send Cdks to M-phase targets (e.g., to break down the nuclear membrane).

Because the cyclic fluctuations of cyclin levels are largely based on the timing of the cell cycle and not on specific events, either the Cdk molecules alone or the Cdk/cyclin complexes regulate the cell cycle. Without a specific concentration of fully activated cyclin/Cdk complexes, the cell cycle cannot proceed through the checkpoints.

Although the cyclins are the main regulatory molecules that determine the forward momentum of the cell cycle, several other mechanisms exist to fine-tune the progress of the cycle with negative, rather than positive, effects (see Negative regulation of the cell cycle). These mechanisms essentially block the progression of the cell cycle until the cell resolves problematic conditions. Molecules that prevent the full activation of Cdks are called Cdk inhibitors. Many of these inhibitor molecules directly or indirectly monitor a particular cell cycle event. The block placed on Cdks by inhibitor molecules is not removed until the specific event that the inhibitor monitors is completed.

Self-Check

What steps are necessary for Cdk to become fully active?

Show/Hide answer.

Cdk must bind to a cyclin and be phosphorylated in the correct position to become fully active.

Cdk Example: Maturation-Promoting Factor (MPF)

A famous example of how cyclins and Cdks work together to control cell cycle transitions is that of maturation-promoting factor (MPF). The name dates to the 1970s, when researchers found that cells in the M phase contained an unknown factor that could force frog egg cells stuck in the G2 phase to enter the M phase. In the 1980s, this mystery molecule, called MPF, was discovered to be a Cdk bound to its M cyclin partner.5

MPF provides a good example of how cyclins and Cdks can work together to drive a cell cycle transition. Like a typical cyclin, M cyclin stays at low levels for much of the cell cycle but builds up as the cell approaches the G2/M transition. As M cyclin accumulates, it binds to Cdks already present in the cell, forming complexes poised to trigger the M phase. Once these complexes receive an additional signal (essentially, an all-clear confirming that the cell’s DNA is intact), they become active and set the events of the M phase in motion.6

The MPF complexes add phosphate tags to several different proteins in the nuclear envelope, resulting in its breakdown (a key event of the early M phase), and they also activate targets that promote chromosome condensation and other M phase events (Figure 11).

Learning Activity: Cell Cycle Controls and Cancer

- Watch the video “Cell Cycle Controls and Cancer” (6:43 min) by Baylor Tutoring Center (2019).

- Answer the following questions:

- List the steps in the control of M phase by maturation-promoting factor (MPF).

- What three external factors regulate MPF?

Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle

The second cell cycle regulatory molecule group is negative regulators, which stop the cell cycle. Remember that in positive regulation, active molecules cause the cycle to progress. The best understood negative regulatory molecules are retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and p21. Retinoblastoma proteins are a group of tumour-suppressor proteins common in many cells. Note that the 53 and 21 designations refer to the functional molecular masses of the proteins (p) in kilodaltons (a dalton is equal to an atomic mass unit, which is the mass of one proton or one neutron or 1 g/mol). Most information about cell cycle regulation comes from research conducted with cells that have lost regulatory control. All three regulatory proteins were discovered to be damaged or non-functional in cells that had begun to replicate uncontrollably (i.e., become cancerous). In each case, the main cause of the unchecked progress through the cell cycle was a faulty copy of the regulatory protein.

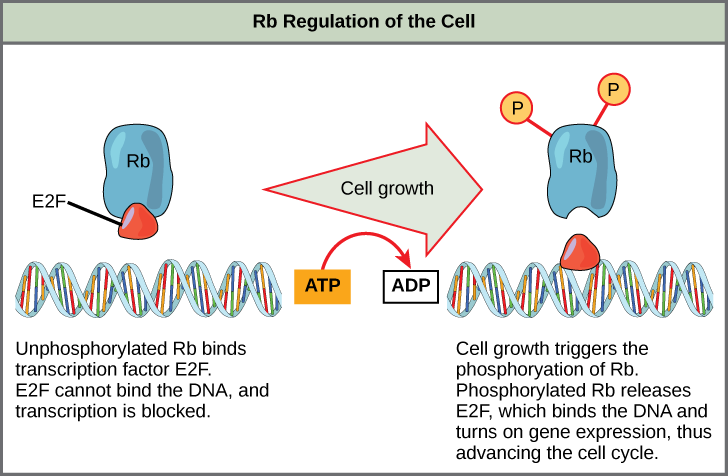

Rb, p53, and p21 primarily act at the G1 checkpoint. Rb, which largely monitors cell size, exerts its regulatory influence on other positive regulator proteins. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to proteins called transcription factors, most commonly, E2F (Figure 12). Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to E2F, the production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. As the cell increases in size, Rb is slowly phosphorylated until it becomes inactivated. Rb releases E2F, which can now turn on the gene that produces the transition protein and remove the block. For the cell to move past each checkpoint, all positive regulators must be “turned on,” and all negative regulators must be “turned off.” Rb halts the cell cycle and releases its hold in response to cell growth.

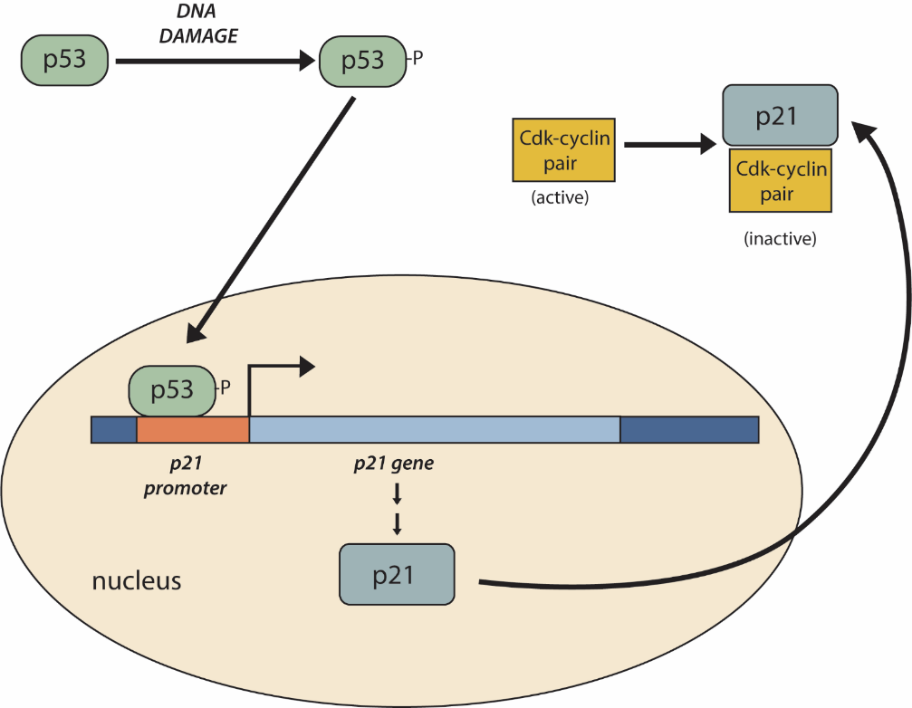

Another important negative regulator of the cell cycle is the tumour suppressor p53. p53 is a multi-functional protein that has a major impact on the commitment of a cell to division because it acts when there is damaged DNA in cells undergoing preparatory processes during G1 (and G2, to a lesser extent). p53 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of over 50 genes that control cell cycle arrest, DNA damage repair, and cell death. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 halts the cell cycle and recruits specific enzymes to repair the DNA. If these enzymes cannot fix the DNA, p53 can trigger apoptosis (cell suicide) to prevent the duplication of damaged chromosomes. As p53 levels rise, the production of p21 is triggered. p21 enforces the halt in the cycle dictated by p53 by binding to and inhibiting the activity of the Cdk/cyclin complexes. As a cell becomes exposed to more stress, higher levels of p53 and p21 accumulate, making it less likely that the cell will move into the S phase.

One example of the actions of p53 occurs at the G1-S checkpoint (Figure 13). In a resting cell, p53 is produced in the cytoplasm and rapidly degraded by the cell. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 is phosphorylated, which stabilizes p53 and prevents its degradation. Phosphorylated p53 translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter of the p21 gene to activate transcription. p21 is a cyclin inhibitor protein, meaning it can bind to and inhibit the activity of cyclin/Cdk complexes. Inhibition of cyclin/Cdks by p21 causes the cell cycle to arrest. This allows time for other p53-controlled genes to repair DNA damage. If these genes cannot fix the DNA, p53 can trigger apoptosis to prevent the duplication of damaged chromosomes.

Additionally, p53 has transcription factor-independent functions. Unit 4, Topic 4 will discuss how loss of p53 function can have severe consequences for the cell cycle. p53 is often known as the “guardian of the genome” because it plays a significant role in cell cycle regulation.

Self-Check

- Compare and contrast the roles of the positive and negative cell cycle regulators.

Show/Hide answer.

Positive cell regulators such as cyclin and Cdk perform tasks that advance the cell cycle to the next stage. Negative regulators such as Rb, p53, and p21 block the progression of the cell cycle until certain events have occurred.

- Rb is a negative regulator that blocks the cell cycle at the G1 checkpoint until the cell achieves a requisite size. What molecular mechanism does Rb employ to halt the cell cycle?

Show/Hide answer.

Rb is active when it becomes dephosphorylated. In this state, Rb binds to E2F, a transcription factor required for the transcription and eventual translation of molecules needed for the G1/S transition. E2F cannot transcribe certain genes when it is bound to Rb. As the cell size increases, Rb becomes phosphorylated, inactivated, and releases E2F. E2F can then promote the transcription of the genes it controls, which produces transition proteins.

- Rb and other proteins that negatively regulate the cell cycle are sometimes called tumour suppressors. Why do you think the name tumour suppressor might be appropriate for these proteins?

Show/Hide answer.

Rb and other negative regulatory proteins control cell division and, therefore, prevent the formation of tumours. Mutations that prevent these proteins from carrying out their function can result in cancer.

Learning Activity: The Cell Cycle Control System

- Watch the following videos:

- “Cell Cycle Checkpoints” (6:12 min) by Johnny Clore (2010).

- “Cell Cycle.mp4” (20:26 min) by Peter Cavnar (2013).

- Answer the following questions:

- What type of protein gives the “go ahead” signal to advance through the cell cycle?

- When are protein kinases active?

- Why are cyclins given that name?

- Comment on the variety of cyclin proteins and Cdks in a cell.

- What has to happen for a Cdk to become active after binding to its cyclin?

- What happens if Cdk stays active during mitosis and never shuts off?

- What has to happen to cyclins for the cell to move to the next cycle phase?

- What type of molecule is maturation-promoting factor (MPF)? What cell cycle stage does it affect when active, and how?

- How does the MPF/cyclin complex shut down when nuclear envelope disintegration is complete?

- What does the cell check for before entering the S phase?

- What happens at the G2 checkpoint?

- What happens at the M phase checkpoint?

- What is the role of p53 in the cell cycle?

- What molecules does p53 regulate? Why?

- What happens if p53 doesn’t function properly?

- What yeast protein was discovered to be important in sensing DNA damage?

- What is the take-home message about how cell cycle checkpoint control works?

Key Concepts and Summary

The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages. In eukaryotes, the cell cycle consists of a long preparatory period called interphase, during which chromosomes replicate. Interphase is divided into G1, S, and G2 phases. The mitotic phase begins with karyokinesis (mitosis), which consists of five stages: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The final stage of the cell division process, and sometimes viewed as the final stage of the mitotic phase, is cytokinesis, during which the cytoplasmic components of the daughter cells are separated either by an actin ring (animal cells) or by cell plate formation (plant cells).

Checkpoints are internal controls that monitor each step of the cell cycle. The cell cycle has three main checkpoints: one near the end of G1, a second at the G2/M transition, and the third during metaphase. Positive regulator molecules allow the cell cycle to advance to the next stage of cell division. Negative regulator molecules monitor cellular conditions and can halt the cycle until the cell meets specific requirements.

Key Terms

anaphase

stage of mitosis during which sister chromatids are separated from each other

cell cycle

ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells

cell cycle checkpoint

mechanism that monitors the preparedness of a eukaryotic cell to advance through the various cell cycle stages and can stop cell cycle progression if specific conditions are not met

cell plate

structure formed during plant cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles, forming a temporary structure (phragmoplast) and fusing at the metaphase plate; ultimately leads to the formation of cell walls that separate the two daughter cells

centriole

rod-like structure constructed of microtubules at the centre of each animal cell centrosome

cleavage furrow

constriction formed by an actin ring during cytokinesis in animal cells that leads to cytoplasmic division

condensin

proteins that help sister chromatids coil during prophase

cyclin

one of a group of proteins that act in conjunction with cyclin-dependent kinases to help regulate the cell cycle by phosphorylating key proteins; the concentrations of cyclins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle

cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)

one of a group of protein kinases that helps to regulate the cell cycle when bound to cyclin; it functions to phosphorylate other proteins that are either activated or inactivated by phosphorylation

cytokinesis

division of the cytoplasm following mitosis that forms two daughter cells

E2F transcription factor

a regulator that activates genes whose products are involved in DNA replication and entry into the S phase of the cell cycle

G0 phase

distinct from the G1 phase of interphase; a cell in G0 is not preparing to divide

G1 phase (also first gap)

first phase of interphase centred on cell growth during mitosis

G2 phase (also second gap)

third phase of interphase during which the cell undergoes final preparations for mitosis

growth factor

a type of extracellular signalling molecule that promotes cell division and survival

interphase

period of the cell cycle leading up to mitosis; includes G1, S, and G2 phases (the interim period between two consecutive cell divisions)

karyokinesis

mitotic nuclear division

kinetochore

protein structure associated with the centromere of each sister chromatid that attracts and binds spindle microtubules during prometaphase

M checkpoint

a checkpoint also known as the spindle assembly checkpoint; this halts mitosis between metaphase and anaphase if chromosomes are not attached properly to kinetochore microtubules

metaphase plate

equatorial plane midway between the two poles of a cell where the chromosomes align during metaphase

metaphase

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes are aligned at the metaphase plate

mitosis (also karyokinesis)

period of the cell cycle during which the duplicated chromosomes are separated into identical nuclei; includes prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase

maturation-promoting factor (MPF)

a Cdk-cyclin complex that promotes cell cycle progression from G2 into mitosis by phosphorylation of proteins involved in mitosis

mitotic (M) phase

period of the cell cycle during which duplicated chromosomes are distributed into two nuclei and cytoplasmic contents are divided; includes karyokinesis (mitosis) and cytokinesis

mitotic spindle

apparatus composed of microtubules that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis

p21

cell cycle regulatory protein that inhibits the cell cycle; its levels are controlled transcriptionally by p53

p53

cell cycle regulatory protein that regulates cell growth and monitors DNA damage; it halts the progression of the cell cycle in cases of DNA damage and may induce apoptosis

prometaphase

stage of mitosis during which the nuclear membrane breaks down and mitotic spindle fibres attach to kinetochores

prophase

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes condense and the mitotic spindle begins to form

quiescent

refers to a cell that is performing normal cell functions and has not initiated preparations for cell division

retinoblastoma protein (Rb)

regulatory molecule that exhibits negative effects on the cell cycle by interacting with a transcription factor E2F

S phase

second, or synthesis, stage of interphase during which DNA replication occurs

telophase

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes arrive at opposite poles, decondense, and are surrounded by a new nuclear envelope

Long Descriptions

Figure 2 Image Description: The karyokinesis (mitosis) stages are as follows:

Prophase

- Chromosomes condense and become visible

- Spindle fibres emerge from the centrosomes

- The nuclear envelope breaks down

- the nucleolus disappears

Prometaphase

- Chromosomes continue to condense

- Kinetochores appear at the centromeres

- Mitotic spindle microtubules attach to kinetochores

- Centrosomes move toward opposite poles

Metaphase

- The mitotic spindle is fully developed, centrosomes are at opposite poles of the cell

- Chromosomes are lined up at the metaphase plate

- Each sister chromatid is attached to a spindle fibre originating from opposite poles

Anaphase

- Cohesion proteins binding the sister chromatids together break down

- Sister chromatids (now called chromosomes) are pulled toward opposite poles

- non-kinetochore spindle fibres lengthen, elongating the cell

Telophase

- Chromosomes arrive at opposite poles and begin to decondense

- Nuclear envelope material surrounds each set of chromosomes

- The mitotic spindle breaks down

Karyokinesis can also include cytokinesis, but not always, and it has the following characteristics:

- Animal cells — a cleavage furrow separates the daughter cells

- Plant cells — a cell plate separates the daughter cells

Figure 9 Image Description: In the graph, cyclin D is present throughout the cell cycle. It increases from zero until the halfway point, where it begins to decrease back to zero. Cyclin E shows up about halfway through the G1 phase and spikes during the transition from the G1 to S phase. It decreases to zero halfway through the S phase. Cyclin A shows up near the end of the G1 phase and gradually increases until its peak halfway through the G2 phase. It sharply drops off at the start of mitosis. Cyclin B shows up at the beginning of the S phase and gradually increases until it peaks during the transition from G2 to mitosis. It sharply drops off halfway through mitosis. [Return to Figure 9]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 10.5 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 10.6 [modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal, Roy van Heesbeen, Wadsworth Center/New York State Department of Health; scale-bar data from Matt Russell] from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is modified and used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 10.7 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 10.8 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 13-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 10.9 from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 13-6 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 10.10 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 10.11 [modification of work by “WikiMiMa”/Wikimedia Commons] from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 10.12 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: Cyclin-dependent kinases by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 10.13 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 13-12 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Baylor Tutoring Center. Cell cycle controls and cancer [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Aug 25, 6:43 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=26cJbmDaH90.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Figures 10.7 to 10.9. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/10-2-the-cell-cycle.

2 Cooper GM. 2000. The cell: a molecular approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9839/.

Johnny Clore. Cell cycle checkpoints [Video]. YouTube. 2010 Apr 8, 6:12 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1EB8q9aR8Hk.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 13: the cell cycle and its regulation. Figures 13-4, 13-6, 13-12. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/78a4b49f-eb14-40a1-9ea7-196821b7d5de.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Cell cycle regulators. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figure cyclin-dependent kinases. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-communication-and-cell-cycle/regulation-of-cell-cycle/a/cell-cycle-regulators.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Phases of the cell cycle. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. AP®︎/college biology, Lesson 5: cell cycle. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-communication-and-cell-cycle/cell-cycle/a/cell-cycle-phases.

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless).

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 10.3C: regulator molecules of the cell cycle. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless)/10%3A_Cell_Reproduction/10.03%3A_Control_of_the_Cell_Cycle/10.3C%3A_Regulator_Molecules_of_the_Cell_Cycle.

6 Mailand N, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Bartek J, Lukas J. 2002. Regulation of G2/M events by Cdc25A through phosphorylation‐dependent modulation of its stability. EMBO J. 21(21):5911-5920. https://www.embopress.org/doi/full/10.1093/emboj/cdf567?pubCode=cgi. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf567.

5 Masui Y. 2001. From oocyte maturation to the in vitro cell cycle: the history of discoveries of maturation-promoting factor (MPF) and cytostatic factor (CSF). Differentiation. 69(1):1-17. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301468109604138?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.690101.

Mr Riddz Science. Mitosis in Drosophila embryo [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Oct 31, 1:35 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERnzwtj4YPs.

Peter Cavnar. Cell cycle.mp4 [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Apr 26, 20:26 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OrdJTP653Sk.

4 Raven PH, Johnson GB, Mason KA, Losos JB, Singer SR. 2013. Biology. 10th ed., AP ed. New York (NY): McGraw Hill. How cells divide; p. 200-201.

1 Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB. 2019. Campbell biology. 10th ed. London (England): Pearson. Cell communication; p. 223, 228.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

3 Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 10.2: the cell cycle, Chapter 10.3: control of the cell cycle. Figures 10.5, 10.10 to 10.13. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Tglab. Early mitotic divisions in a Drosophila embryo [Video]. YouTube. 2008 Aug 2, 0:32 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSKh-GLQn4E.

ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells

period of the cell cycle leading up to mitosis; includes G1, S, and G2 phases (the interim period between two consecutive cell divisions)

period of the cell cycle during which duplicated chromosomes are distributed into two nuclei and cytoplasmic contents are divided; includes karyokinesis (mitosis) and cytokinesis

division of the cytoplasm following mitosis that forms two daughter cells

period of the cell cycle during which the duplicated chromosomes are separated into identical nuclei; includes prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase

mitotic nuclear division

first phase of interphase centered on cell growth during mitosis

second, or synthesis, stage of interphase during which DNA replication occurs

third phase of interphase during which the cell undergoes final preparations for mitosis

rod-like structure constructed of microtubules at the center of each animal cell centrosome

apparatus composed of microtubules that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes condense and the mitotic spindle begins to form

stage of mitosis during which the nuclear membrane breaks down and mitotic spindle fibres attach to kinetochores

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes are aligned at the metaphase plate

stage of mitosis during which sister chromatids are separated from each other

stage of mitosis during which chromosomes arrive at opposite poles, decondense, and are surrounded by a new nuclear envelope

one of a group of proteins that act in conjunction with cyclin-dependent kinases to help regulate the cell cycle by phosphorylating key proteins; the concentrations of cyclins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle

one of a group of protein kinases that helps to regulate the cell cycle when bound to cyclin; it functions to phosphorylate other proteins that are either activated or inactivated by phosphorylation

proteins that help sister chromatids coil during prophase

protein structure associated with the centromere of each sister chromatid that attracts and binds spindle microtubules during prometaphase

equatorial plane midway between the two poles of a cell where the chromosomes align during metaphase

constriction formed by an actin ring during cytokinesis in animal cells that leads to cytoplasmic division

structure formed during plant cell cytokinesis by Golgi vesicles, forming a temporary structure (phragmoplast) and fusing at the metaphase plate; ultimately leads to the formation of cell walls that separate the two daughter cells

distinct from the G1 phase of interphase; a cell in G0 is not preparing to divide

refers to a cell that is performing normal cell functions and has not initiated preparations for cell division

a type of extracellular signalling molecule that promotes cell division and survival

mechanism that monitors the preparedness of a eukaryotic cell to advance through the various cell cycle stages and can stop cell cycle progression if specific conditions are not met

a checkpoint also known as the spindle assembly checkpoint; this halts mitosis between metaphase and anaphase if chromosomes are not attached properly to kinetochore microtubules

a Cdk-cyclin complex that promotes cell cycle progression from G2 into mitosis by phosphorylation of proteins involved in mitosis

regulatory molecule that exhibits negative effects on the cell cycle by interacting with a transcription factor E2F

cell cycle regulatory protein that regulates cell growth and monitors DNA damage; it halts the progression of the cell cycle in cases of DNA damage and may induce apoptosis

cell cycle regulatory protein that inhibits the cell cycle; its levels are controlled transcriptionally by p53

a regulator that activates genes whose products are involved in DNA replication and entry into the S phase of the cell cycle