4.1 Signalling Molecules and Cellular Receptors

Introduction

Cell signalling, also called signal transduction, describes the ability of cells to respond to stimuli from their environment. Examples include healing a wound after injury, activating the immune system in response to pathogens, and changing gene expression during different developmental stages. Communication between cells is called intercellular signalling, and communication within a cell is called intracellular signalling. An easy way to remember the distinction is by understanding the Latin origin of the prefixes: inter- means “between” (for example, intersecting lines are those that cross each other), and intra- means “inside” (like intravenous).

Unit 4 will examine the basic principles of how cells communicate with one another will be examined. First, it will look at how cell-cell signalling works, and then it will consider different kinds of short- and long-range signalling that happen in the human body.

Unit 4, Topic 1 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 4, Topic 1, you will be able to:

- Describe four types of signalling mechanisms found in multicellular organisms.

- Compare internal receptors with cell-surface receptors.

- Recognise the relationship between a ligand’s structure and its mechanism of action.

| Unit 4, Topic 1—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions from Unit 4, Topic 1 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Overview of cell signalling. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How neurons communicate. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Categories of cell signalling. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Membrane receptors. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Ligand-gated ion channels. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: G-Protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Enzyme-linked receptors. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary — Receptors and secondary messenger systems. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary — Introduction to Cell Signalling. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Mechanisms of hormone action. | 10 |

Overview of Signalling — Molecules and Receptors

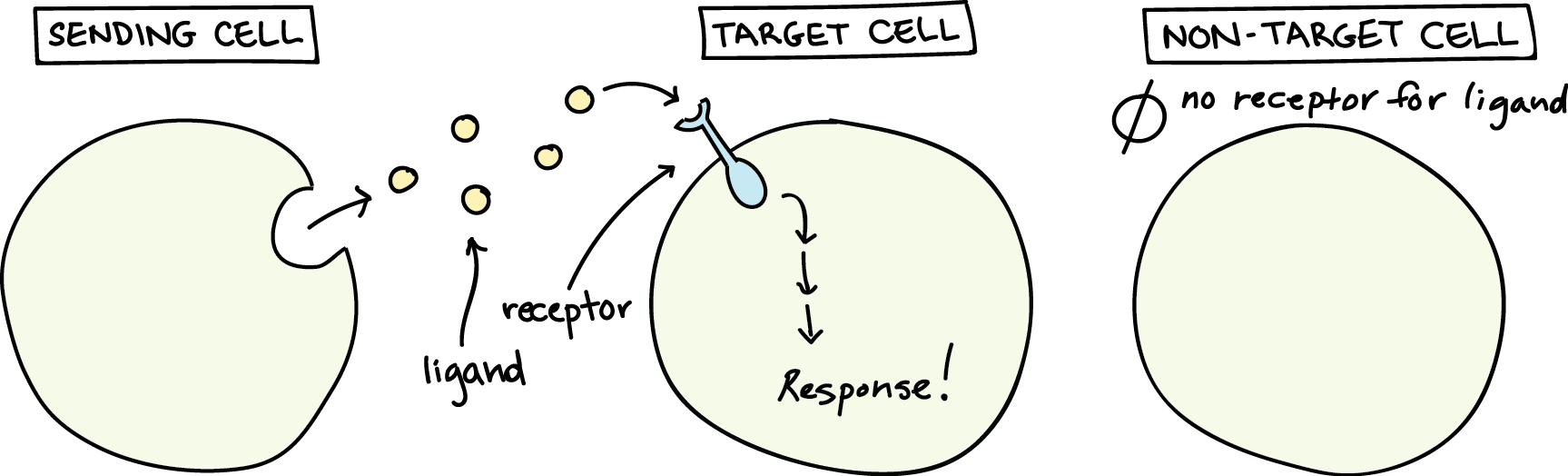

Chemical signals are released into the extracellular space by signalling cells in the form of small, usually volatile or soluble molecules called ligands. A ligand is a molecule that binds another specific molecule, in some cases, delivering a signal in the process (Figure 1). Ligands can thus be thought of as chemical messages. Ligands interact with proteins in target cells, which are cells affected by chemical signals; these proteins are called receptors. Ligands and receptors exist in several varieties; however, a specific receptor typically only binds to a specific ligand. Not all cells can “hear” a particular chemical message. Detecting a signal (being a target cell) requires that cell to have the right receptor for that signal.

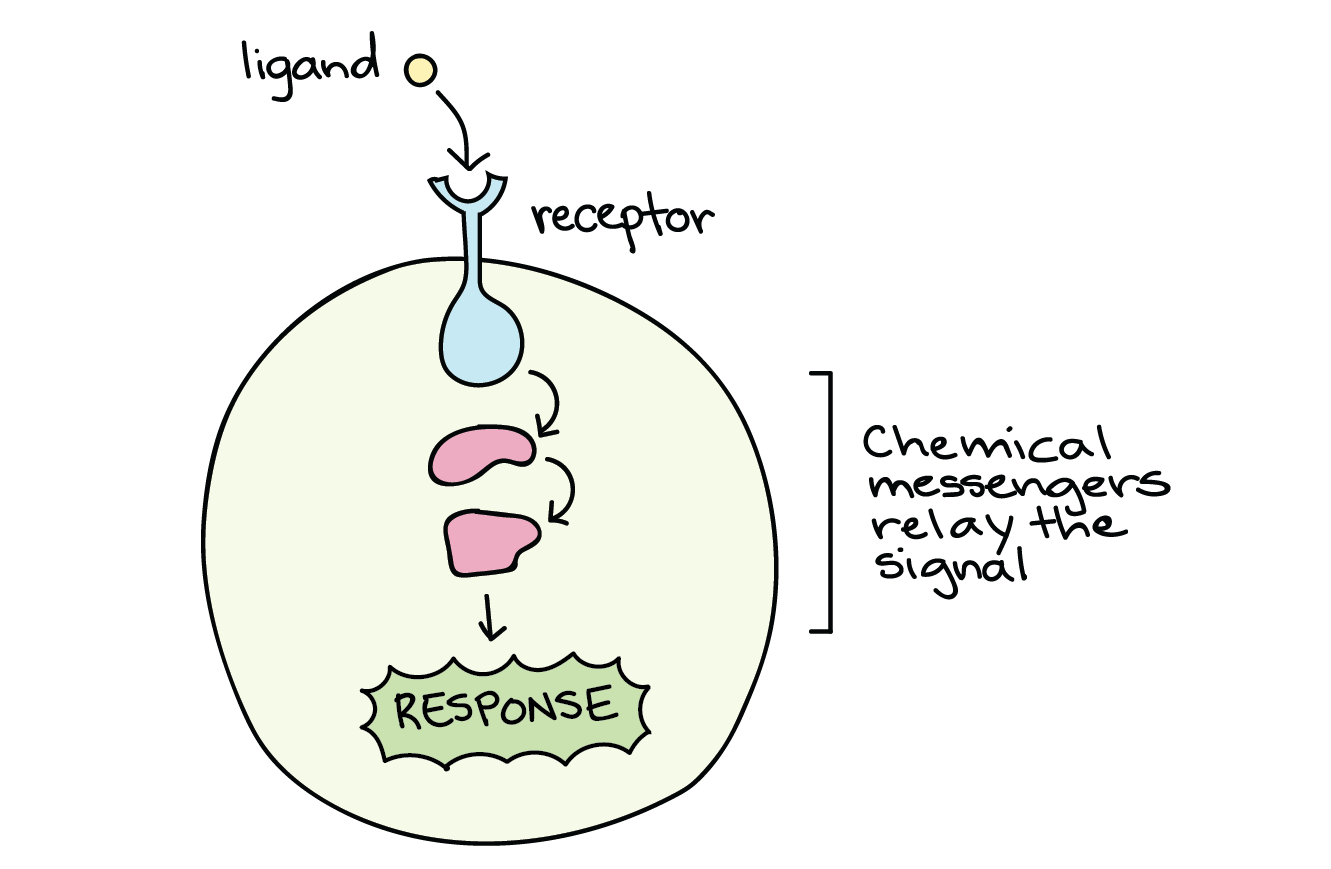

When a signalling molecule binds to its receptor, it alters the shape or activity of the receptor, triggering a change inside the cell (Figure 2). The message carried by a ligand often relays through a chain of chemical messengers inside the cell. Ultimately, it leads to a change in the cell, such as an alteration in the activity of a gene or even the induction of a whole process, such as cell division or protein synthesis. Thus, the original intercellular (between-cells) signal converts into an intracellular (within-cell) signal that triggers a response.

Self-Check

From An Interactive Introduction to Organismal and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed. (Bierema 2021). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Forms of Cell Signalling

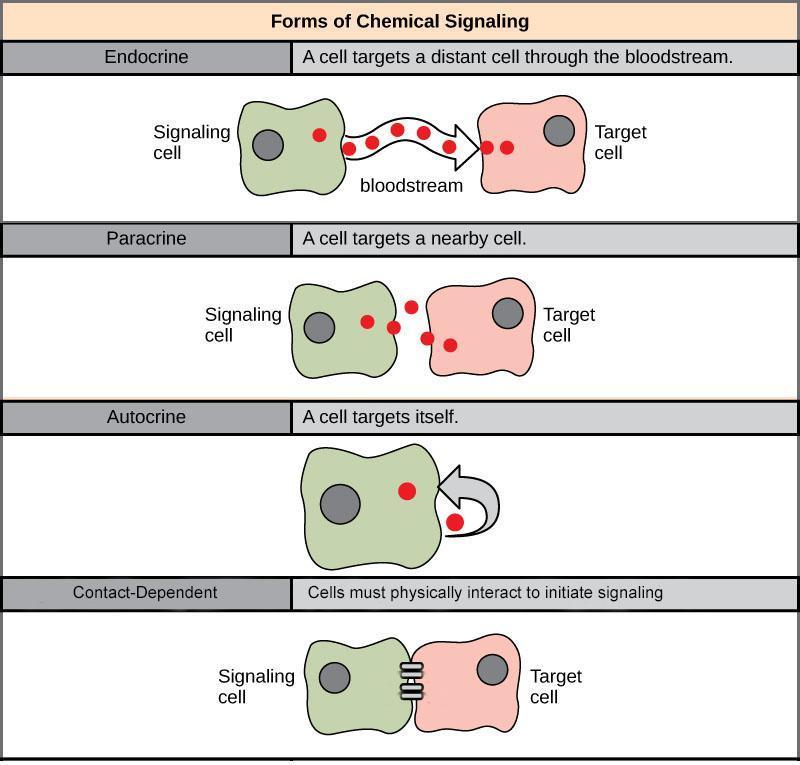

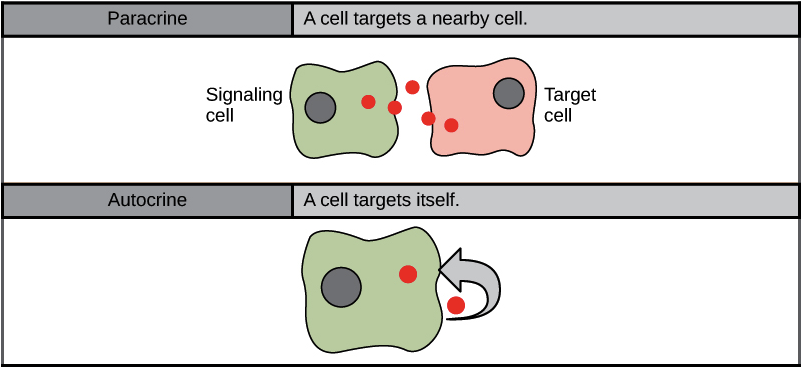

Cell signalling can divide into the following four major categories depending on how far the signalling molecule is from the receptor and where the receptor is (Figure 3):

- Long-range signalling (endocrine)

- Short-range signalling (paracrine)

- Self-activation (autocrine)

- Direct activation (contact-dependent, also called juxtacrine)

Learning Activity: Overview of Cell Signalling

- Watch the video “Overview of cell signalling” (8:48 min) by Khan Academy (2015).

- Complete the following exercise:

From An Interactive Introduction to Organismal and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed. (Bierema 2021). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Endocrine Signalling

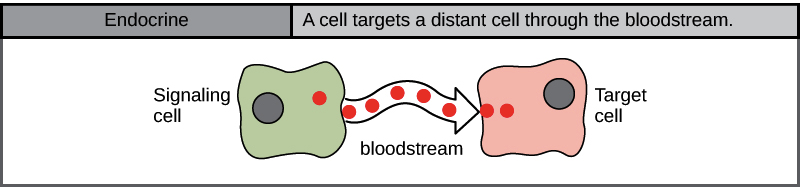

When cells need to transmit signals over long distances, they often use the circulatory system as a distribution network for the messages they send. In long-distance endocrine signalling, specialized cells produce signals and release them into the bloodstream, carrying them to target cells in distant parts of the body (Figure 4). Signals from distant cells are called endocrine signals, and they originate from endocrine cells. In the body, many endocrine cells are in endocrine glands, such as the thyroid gland, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, as well as the gonads and pancreas. Endocrine signals usually produce a slower response but have a longer-lasting effect. The ligands released in endocrine signalling are called hormones, signalling molecules produced in one part of the body but affecting other body regions some distance away. Each endocrine gland releases one or more types of hormones, many of which are master regulators of development and physiology.

For example, the pituitary gland releases growth hormone (GH), which promotes growth, particularly of the skeleton and cartilage. Like most hormones, GH affects many different types of cells throughout the body. However, cartilage cells provide one example of how GH functions: it binds to receptors on the surface of these cells and encourages them to divide.

Hormones travel large distances between endocrine cells and their target cells via the bloodstream, which is a relatively slow way to move throughout the body. Because of their form of transport, hormones become diluted and are present in low concentrations when they act on their target cells. This is different from paracrine signalling, in which local concentrations of ligands can be very high.

Paracrine Signalling

Signals acting locally between cells sitting close together are known as paracrine signals (Figure 5). Paracrine signals move by diffusion through the extracellular matrix. These types of signals usually elicit quick responses that last only a short period. The body keeps this response localized by using enzymes to degrade paracrine ligand molecules or using neighbouring cells to remove them. Removing the signals re-establishes the concentration gradient for the signal, allowing for quick diffusion through the intracellular space if released again.

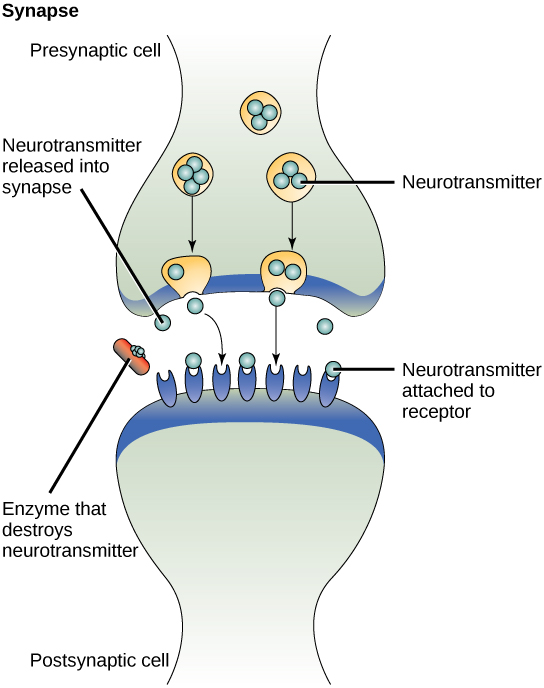

One example of paracrine signalling is the transfer of signals across synapses between nerve cells. A nerve cell consists of a cell body, several short, branched extensions called dendrites that receive stimuli, and a long extension called an axon, which transmits signals to other nerve cells or muscle cells. The junction between nerve cells where signal transmission occurs is called a synapse. A synaptic signal is a chemical signal that travels between nerve cells. Fast-moving electrical impulses propagate the signals within the nerve cells. When the sending neuron fires, an electrical impulse quickly moves through the cell, travelling down a long, fibre-like extension called an axon. When the impulse reaches the synapse, it triggers the release of chemical ligands called neurotransmitters from the presynaptic cell (the cell emitting the signal), which quickly cross the small gap between the neurons. The neurotransmitters are transported across very small distances (20–40 nm) between nerve cells, called chemical synapses (Figure 6). The small distance between nerve cells allows the signal to travel quickly; this enables an immediate response, such as, “Take your hand off the stove!”

When the neurotransmitters arrive at the receiving cell, they bind to receptors and cause a chemical change inside the cell (often opening ion channels and changing the electrical potential across the membrane). The neurotransmitters released into the chemical synapse degrade quickly or get reabsorbed by the presynaptic cell so that the recipient nerve cell can recover quickly and prepare to respond rapidly to the next synaptic signal (Figure 6).

Learning Activity: How Neurons Communicate

- Watch the video “How Neurons Communicate” (1:18 min) by BrainFacts.org (2018).

- Complete the following exercises:

From An Interactive Introduction to Organismal and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed. (Bierema 2021), CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

From An Interactive Introduction to Organismal and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed. (Bierema 2021), CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Autocrine Signalling

Signalling cells produce autocrine signals and can also bind to the released ligand (Figure 5). This means the signalling cell and the target cell can be the same or a similar cell (the prefix auto- means self, a reminder that the signalling cell sends a signal to itself). This type of signalling often occurs during the early development of an organism to ensure cells develop into the correct tissues and take on the proper function. Autocrine signalling also regulates pain sensation and inflammatory responses. Further, if a cell becomes infected with a virus, it can signal itself to undergo programmed cell death, killing the virus in the process. In some cases, the released ligand also influences neighbouring cells of the same type. In embryological development, this process of stimulating a group of neighbouring cells may help to direct the differentiation of identical cells into the same cell type, thus ensuring the proper developmental outcome.

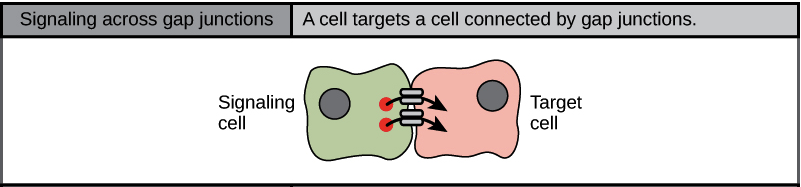

Direct Signalling Across Gap Junctions

Gap junctions in animals and plasmodesmata in plants are connections between the plasma membranes of neighbouring cells. These water-filled channels allow small signalling molecules, called intracellular mediators, to diffuse between the two cells (Figure 7). Small molecules, such as calcium ions (Ca2+), can move between cells, but large molecules, like proteins and DNA, cannot fit through the channels. The specificity of the channels ensures that the cells remain independent but can quickly and easily transmit signals. The transfer of signalling molecules communicates the current state of the cell that is directly next to the target cell; this allows a group of cells to coordinate their response to a signal that only one of them may have received. In plants, plasmodesmata are ubiquitous, making the entire plant into a giant communication network.

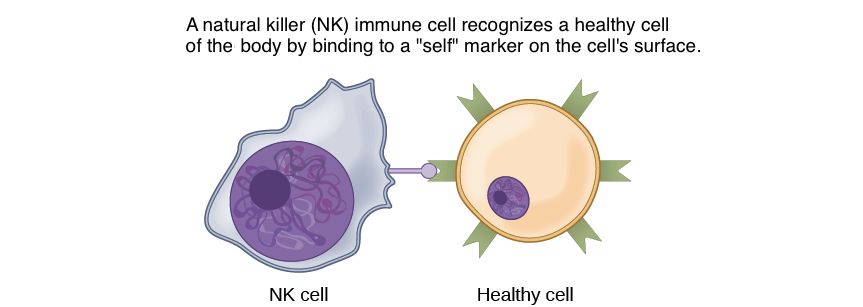

In another form of direct signalling, two cells may bind to one another because they carry complementary proteins on their surfaces. When the proteins bind to one another, this interaction changes the shape of one or both proteins, transmitting a signal. This kind of signalling is especially important in the immune system, where immune cells use cell-surface markers to recognise “self” cells (the body’s own cells) and cells infected by pathogens (Figure 8).

Learning Activity: Categories of Cell Signalling

- Watch the video “Cell Signaling in ONE MINUTE! Autocrine, Paracrine, Juxtacrine and Endocrine Signaling | MCAT |” (1:06 min) by QuickSci (2020).

- Describe the differences between the four main types of cell signalling.

Types of Receptors

Receptors are protein molecules in the target cell or on its surface that bind ligands. There are two types of receptors: internal receptors and cell-surface receptors.

Internal Receptors

Internal receptors, also known as intracellular or cytoplasmic receptors, are found in the cytoplasm or nucleus of the cell and respond to small hydrophobic ligand molecules that can travel across the plasma membrane. The hydrophobicity of these ligands allows them to cross the plasma membrane. For example, the primary receptors for hydrophobic steroid hormones, such as the sex hormones estradiol (an estrogen) and testosterone, are intracellular.

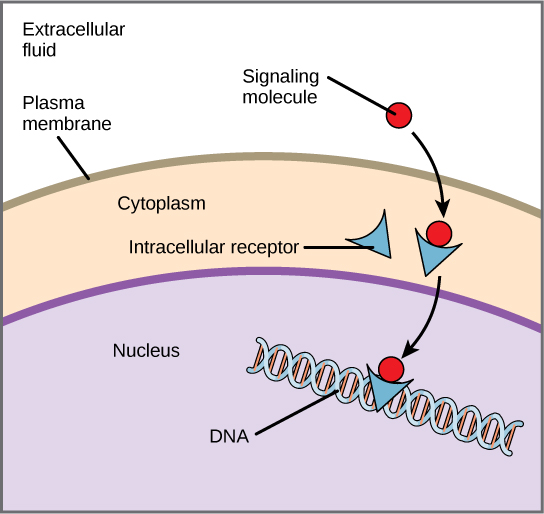

Once inside the cell, many of these molecules bind to proteins that regulate mRNA synthesis (transcription) to mediate gene expression. Gene expression is the cellular process of transforming the information in a cell’s DNA into a sequence of amino acids, which ultimately form a protein. Intracellular receptors often function as a transcriptional activator by binding specific DNA elements, altering the transcription of downstream genes. Intracellular receptors commonly have three domains: ligand-binding domain, DNA-binding domain, and transactivation domain. When the ligand binds to the internal receptor, it triggers a conformational change that exposes a DNA-binding site on the protein. The ligand-receptor complex moves into the nucleus, then binds to specific regulatory regions of the chromosomal DNA and promotes the initiation of transcription (Figure 9). Transcription is the process of copying the information in a cell’s DNA into a special form of RNA called messenger RNA (mRNA); the cell uses information in the mRNA (which moves out into the cytoplasm and associates with ribosomes) to link specific amino acids in the correct order, producing a protein. Internal receptors can directly influence gene expression without passing the signal on to other receptors or messengers. The signal terminates when the hormone concentration lowers.

Cortisol is an example of a hormone that binds an intracellular receptor. The adrenal cortex releases cortisol, which diffuses into the bloodstream attached to serum albumin and steroid hormone-binding globulin. After diffusing through the plasma membrane, it binds to the cortisol receptor (intracellular receptor) in the cytosol and forms a homodimer, exposing a nuclear localization signal (NLS). Exposure of the NLS targets the complex to the nucleus.

Cell-Surface Receptors

Cell-surface receptors, also known as transmembrane receptors, are cell surface, membrane-anchored (integral) proteins that bind to external ligand molecules. This receptor type spans the plasma membrane and performs signal transduction, where an extracellular signal converts into an intracellular signal. Ligands that interact with cell-surface receptors do not have to enter the cell that they affect. Cell-surface receptors are also known as cell-specific proteins or markers because they are specific to individual cell types.

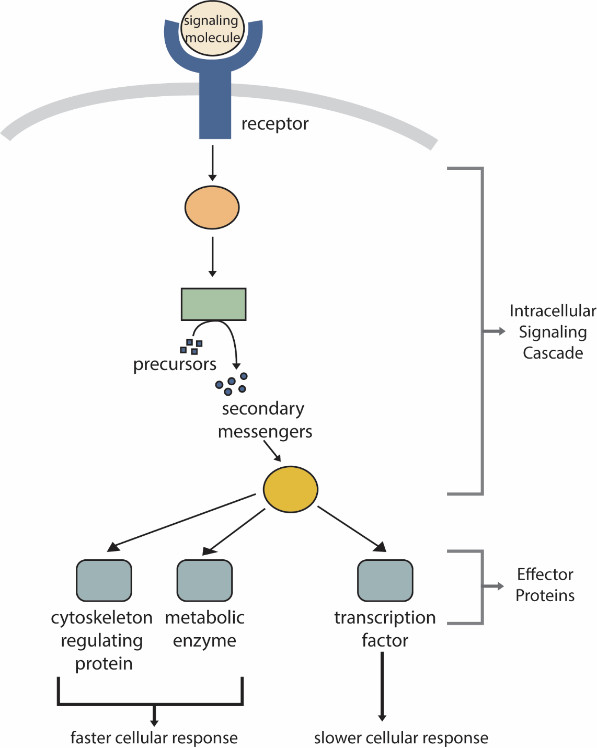

Receptors, even at high density, represent only a minute fraction of the cell’s surface area and, therefore, an even smaller fraction of the volume of the cell. Therefore, activating a receptor must be amplified to initiate cellular activities (e.g., locomotion, growth, cell cycle progression). Thus, one of the first things a receptor does upon activation or ligand binding is to initiate an intracellular signalling cascade (Figure 10). The molecules within an intracellular signalling cascade will produce small intracellular molecules that amplify the cellular response to the primary signalling molecules. These molecules are termed secondary messengers (Figure 10).

Because cell-surface receptor proteins are fundamental to normal cell functioning, it should be no surprise that a malfunction in any of these proteins could have severe consequences. Errors in the protein structures of specific receptor molecules have played a role in hypertension (high blood pressure), asthma, heart disease, and cancer.

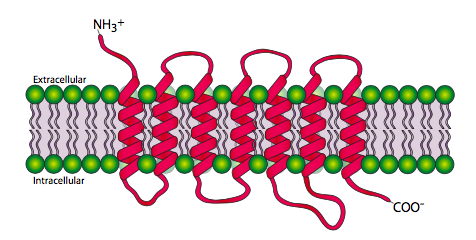

Each cell-surface receptor has three main components: an extracellular ligand-binding domain (“outside of cell”), a hydrophobic membrane-spanning region called a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain inside the cell. The size and extent of each of these domains vary widely, depending on the type of receptor. The hydrophobic region may consist of multiple stretches of amino acids that crisscross the membrane (Figure 11).

Cell-surface receptors are involved in most signalling in multicellular organisms. There are three general categories of cell-surface receptors: ligand-gated ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors, and enzyme-linked receptors.

How Viruses Recognise a Host

Unlike living cells, many viruses do not have a plasma membrane or any other structures necessary to sustain metabolic life. Some viruses are simply composed of an inert protein shell enclosing DNA or RNA. Viruses must reproduce by invading a living cell, serving as a host, and taking over its cellular apparatus. But how does a virus recognise its host?

Viruses often bind to cell-surface receptors on the host cell. For example, the virus that causes human influenza (flu) binds specifically to receptors on membranes of cells in the respiratory system. Chemical differences in the cell-surface receptors among hosts mean that a virus infecting a specific species (e.g., humans) cannot often infect another species (e.g., chickens).

However, viruses have very small amounts of DNA or RNA compared to humans; as a result, viral reproduction can occur rapidly. Viral reproduction invariably produces errors that can lead to changes in newly produced viruses; these changes mean that the viral proteins that interact with cell-surface receptors may evolve in such a way that they can bind to receptors in a new host. Such changes happen randomly and quite often in the reproductive cycle of a virus; however, the changes only matter if a virus with new binding properties comes into contact with a suitable host. In the case of influenza, this situation can occur where animals and people are in close contact, such as poultry and swine farms.1,2 Once a virus jumps the former “species barrier” to a new host, it can spread quickly. Scientists watch newly appearing viruses (called emerging viruses) closely in the hope that such monitoring can reduce the likelihood of global viral epidemics.

Learning Activity: Membrane Receptors

- Watch the video “Membrane Receptors | Nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy” (7:58 min) by Khanacademymedicine (2014).

- Answer the following questions before reading further about the details of each type of receptor:

- What are the transmembrane proteins called that receive information from outside the cell? What “type” of membrane protein would you classify these as (see Unit 2, Topic 1)?

- What is another name for a signalling molecule? What are three examples found in cells?

- List the multiple cellular responses that can occur after ligand-receptor complexes form.

- Why do certain pharmaceutical drugs only target certain cell types?

- What happens during signal transduction?

- Describe the “lock and key” model for ligand-receptor complexes.

- What is “induced fit”?

- List three groups of cell receptors.

Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

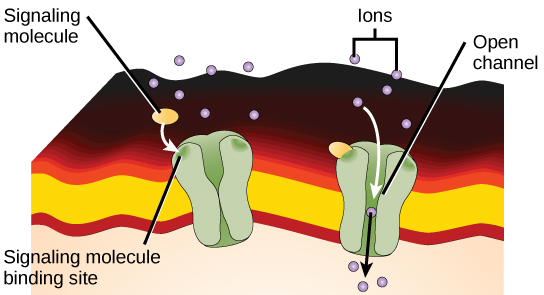

Ligand-gated ion channels act as receptors that bind a ligand, which opens the channel through the membrane and allows specific ions to pass through. This type of cell-surface receptor has an extensive membrane-spanning region to form a channel. In order to interact with the double layer of phospholipid fatty acid tails that form the centre of the plasma membrane, many amino acids in the membrane-spanning region are hydrophobic. Conversely, the amino acids lining the inside of the channel are hydrophilic to allow for the passage of water or ions. When a ligand binds to the extracellular region of the channel, there is a conformational change in the protein’s structure that allows ions such as sodium, calcium, magnesium, and hydrogen to pass through (Figure 12).

When a ligand binds to the extracellular region of the channel, the protein’s structure changes in such a way that ions of a particular type, such as Ca2+, can pass through. In some cases, the reverse is true: the channel is usually open, and ligand binding causes it to close. Changes in ion levels inside the cell can change the activity of other molecules, such as ion-binding enzymes and voltage-sensitive channels, to produce a response. Neurons, or nerve cells, have ligand-gated channels bound by neurotransmitters.

Learning Activity: Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

- Watch the video “Ligand Gated Ion Channels | Nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy” (7:21 min) by Khanacademymedicine (2014).

- Answer the following questions:

- How would you describe such a channel?

- In what cell type are they most abundant?

- What does ligand binding result in?

G-Protein-Coupled Receptors

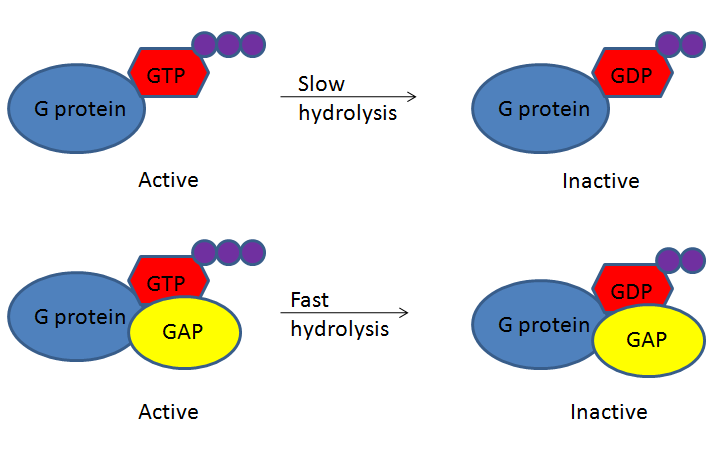

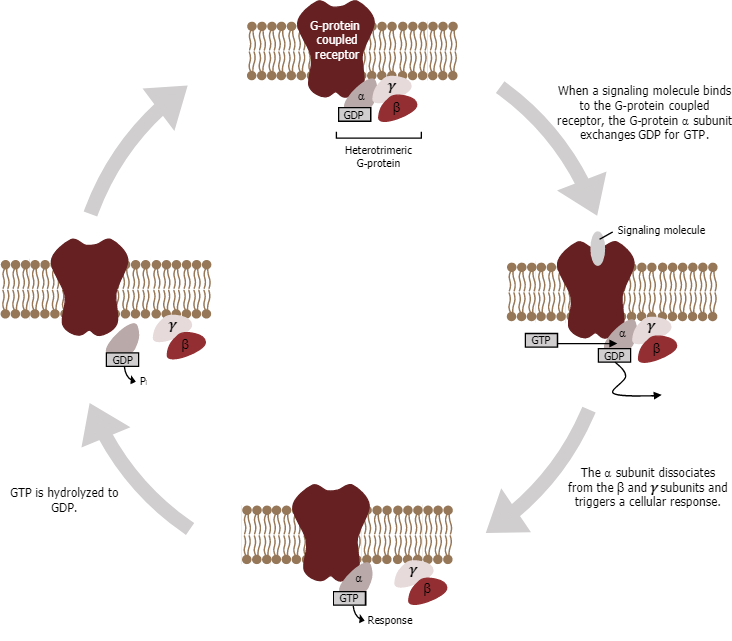

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) bind a ligand and activate a membrane protein called a G-protein. G-proteins are GTPases that hydrolyze a bound GTP to GDP, where the GDP molecule remains bound to the GTPase. Although the GTPase can hydrolyze GTP spontaneously, the GTPase-activating protein, GAP, greatly speeds up the hydrolysis rate. When GDP binds, the protein becomes inactive. Cycling the system back to GTP and activating the protein does not involve re-phosphorylating the GDP; instead, the GDP must be removed and exchanged for a new GTP. An accessory protein, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), facilitates this exchange (Figure 13).

The activated G-protein then interacts with either an ion channel or an enzyme in the membrane (Figure 14). All GPCRs have seven transmembrane domains, but each receptor has its own specific extracellular domain and G-protein-binding site. GPCRs are diverse and bind many different types of ligands. One particularly interesting class of GPCRs is the odorant (scent) receptors. There are about 800 of them in humans, and each binds its own “scent molecule” — such as a particular chemical in perfume or a specific compound released by rotting fish — and causes a signal to be sent to the brain, making people smell a smell.

Cell signalling using GPCRs occurs as a cyclic series of events (Figure 14). Before the ligand binds, the inactive G-protein can bind to a newly revealed site on the receptor specific for its binding. Once the G-protein binds to the receptor, the resulting change in shape activates the G-protein, which releases GDP and picks up GTP. The subunits of the G-protein then split into the α subunit and the βγ subunit. One or both of these G-protein fragments may be able to activate other proteins as a result. After a while, the GTP on the active α subunit of the G-protein undergoes hydrolysis to GDP, and the βγ subunit is deactivated. The subunits reassociate to form the inactive G-protein, and the cycle begins anew.

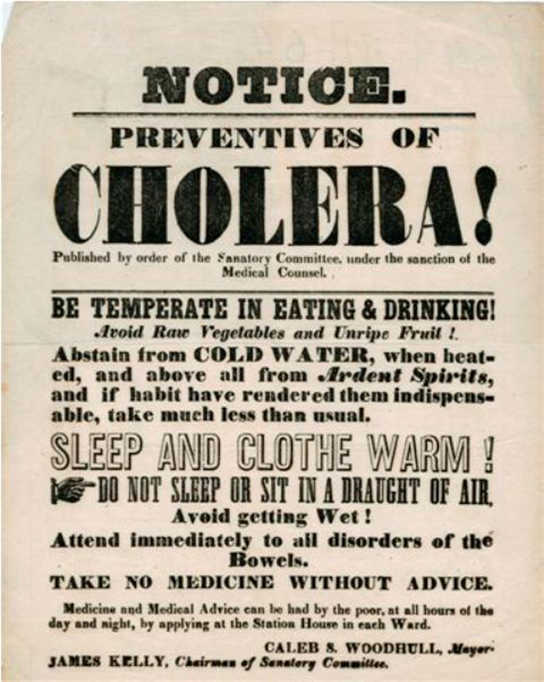

GPCRs have been extensively studied, so much has been learned about their roles in maintaining health. Bacteria pathogenic to humans can release poisons to interrupt specific GPCR functions, leading to illnesses like pertussis, botulism, and cholera. For example, in cholera (Figure 15), the water-borne bacterium Vibrio cholerae produces a toxin, choleragen, that binds to cells lining the small intestine. The toxin then enters these intestinal cells, where it modifies a G-protein that controls the opening of a chloride channel and causes it to remain continuously active, resulting in large losses of fluids from the body and potentially fatal dehydration as a result.

Learning Activity: G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

- Watch the following videos:

- “G Protein Coupled Receptors | Nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy” (12:47 min) by Khanacademymedicine (2014).

- “G Protein Signaling – Handwritten Cell & Molecular Biology” (10:49 min) by Sketchy Medicine (2016).

- “Signal Transduction Animation” (2:25 min) by Tzbiology (2011).

- Answer the following questions while watching the videos:

- How many types of GPCRs do humans have?

- What can GPCRs regulate in the human body?

- How many transmembrane domains do GPCRs have? Describe their topology.

- To what nucleotides can G-proteins bind?

- How many subunits do G-proteins have? What is each subunit called? What is the name of this arrangement?

- Which G-protein subunits are attached to the membrane? How are they attached to membranes?

- Is a GDP-bound G-protein active?

- How does the conformational change in the GPCR after ligand binding affect the alpha subunit of the G-protein? What is the consequence?

- What type of target proteins can the GTP-bound alpha G-protein subunit regulate?

- What happens when adenylyl cyclase is activated by the GTP-bound alpha G-protein subunit?

- How long can this regulation go on? What stops the process? How are clathrin-coated pits involved?

- Describe the relationship between GPCRs and the fight or flight response.

Enzyme-Linked Receptors

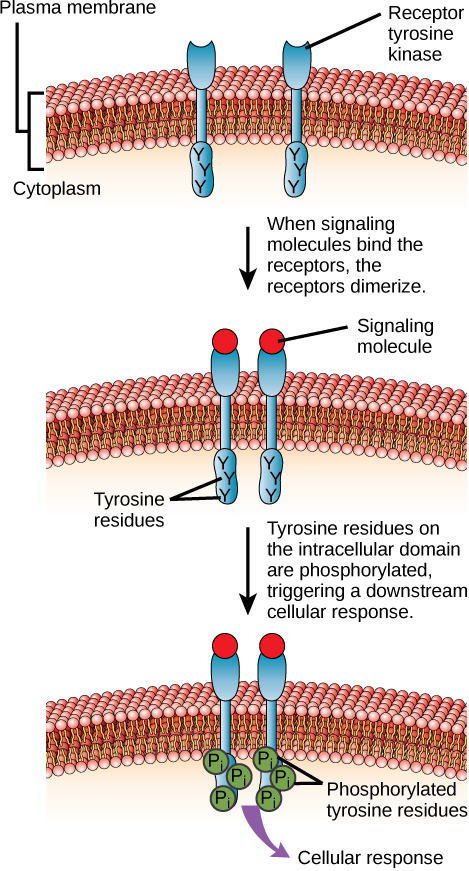

Enzyme-linked receptors are cell-surface receptors with intracellular domains associated with an enzyme. In some cases, the receptor’s intracellular domain is an enzyme itself. The enzyme-linked receptors usually have large extracellular and intracellular domains, but the membrane-spanning region consists of a single alpha-helical region of the peptide strand. When a ligand binds to the extracellular domain, a signal is transferred through the membrane, activating the enzyme. Activation of the enzyme sets off a chain of events within the cell, eventually leading to a response.

One example of this type of enzyme-linked receptor is the tyrosine kinase family of receptors (Figure 16). A kinase is an enzyme that transfers phosphate groups from ATP to another protein. Kinases add a phosphate group to the hydroxyl group of serine, threonine, and/or tyrosine residues of the protein substrate. Various kinases have names related to the substrate they phosphorylate. Phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues often activates enzymes. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues can either affect the activity of an enzyme or create a binding site that interacts with downstream components in the signalling cascade.

The tyrosine kinase receptor transfers phosphate groups to the amino acid tyrosine (tyrosine residues). First, signalling molecules bind to the extracellular domain of two nearby tyrosine kinase receptors. The two neighbouring receptors then bond together or dimerize. Phosphates are then added to tyrosine residues on the intracellular domain of the receptors (mutual phosphorylation). The phosphorylated residues can then transmit the signal to the next messenger within the cytoplasm.

Receptor tyrosine kinases are crucial to many signalling processes in humans. For instance, they bind to growth factors, signalling molecules that promote cell division and survival. Growth factors include platelet-derived growth factor, which participates in wound healing, and nerve growth factor, which certain types of neurons require a continual supply of to stay alive. Because of their role in growth factor signalling, receptor tyrosine kinases are essential in the body. However, their activity must stay balanced as overactive growth factor receptors are associated with some types of cancers.

Learning Activity: Enzyme-Linked Receptors

- Watch the video “Enzyme Linked Receptors | Nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy” (8:50 min) by Khanacademymedicine (2014) before reading further about the next type of receptor.

- Answer the following questions while watching the video:

- What gets activated when a ligand binds to an enzyme-linked receptor? What is this type of receptor referred to as?

- Where is the enzymatic domain located?

- What are the most widely recognised enzyme-linked receptors called? What clue does their name provide about their biochemical activities? What general processes do they regulate in a cell?

- What are their ligands called?

- What happens when a ligand binds a receptor tyrosine kinase?

- Why do receptor tyrosine kinases need to work together in pairs?

- What is the result of cross phosphorylation?

- Where does signal transduction end within a cell?

- To which famous hormone does a receptor tyrosine kinase bind?

- What happens when a receptor tyrosine kinase is not working properly?

Learning Activity: Summary — Receptors and Second Messenger Systems

- Watch the video “Receptors and second messenger system; G-protein, enzyme-linked and ligand gated ion channels” (3:12 min) by Pharmacology Animation (2019). Make your own notes before you proceed to the next section.

Signalling Molecules

Produced by signalling cells and the subsequent binding to receptors in target cells, ligands act as chemical signals that travel to the target cells to coordinate responses. The types of molecules that serve as ligands vary greatly and range from small proteins to small ions like calcium (Ca2+). Others are hydrophobic molecules, like steroids, and gases, like nitric oxide. This section looks at some examples of different types of ligands.

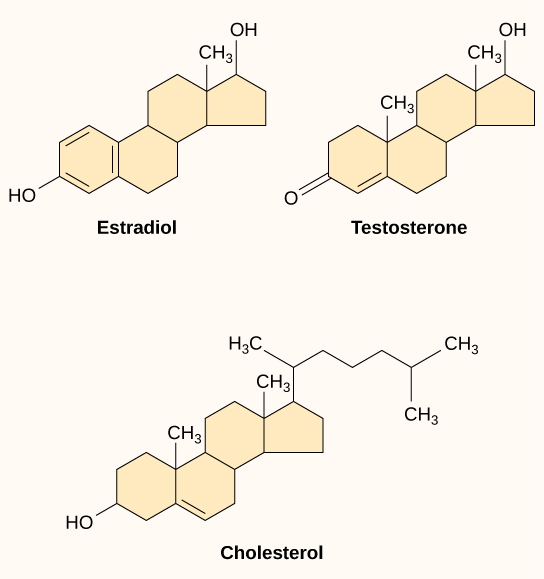

Ligands That Can Enter the Cell

Small hydrophobic ligands can directly diffuse through the plasma membrane and interact with internal receptors in the nucleus or cytoplasm. In the human body, some of the most crucial ligands of this type are the steroid hormones. Steroids are lipids with a hydrocarbon skeleton with four fused rings; different steroids have different functional groups attached to the carbon skeleton. Familiar steroid hormones include the female sex hormone, estradiol (a type of estrogen); the male sex hormone, testosterone; and cholesterol, a crucial structural component of biological membranes and a precursor of steroid hormones (Figure 17). Other hydrophobic hormones include thyroid hormones and vitamin D (synthesized in the skin using energy from light). Because they are hydrophobic, these hormones do not have trouble crossing the plasma membrane, but they must bind to carrier proteins to travel through the (watery) bloodstream.

Water-Soluble Ligands

Water-soluble ligands are polar and, therefore, cannot pass through the plasma membrane unaided; sometimes, they are too large to pass through the membrane at all. Instead, most water-soluble ligands bind to the extracellular domain of cell-surface receptors. This group of ligands is quite diverse and includes small molecules, peptides, and proteins.

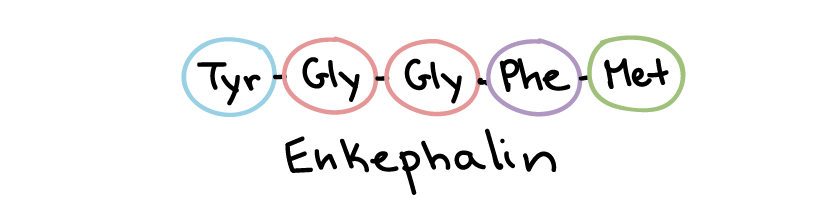

Peptide (protein) ligands make up the largest and most diverse class of water-soluble ligands (Figure 18). For instance, growth factors, hormones (e.g., insulin), and certain neurotransmitters fall into this category. Peptide ligands can range from just a few amino acids long, as in the pain-suppressing enkephalins, to a hundred or more amino acids in length.

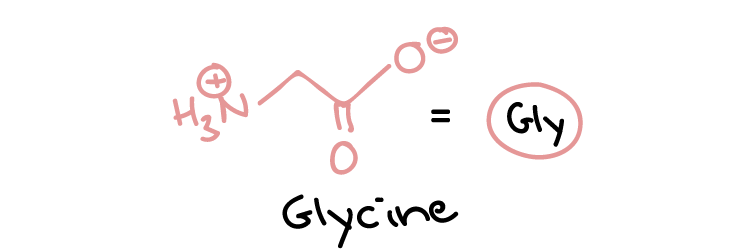

Some neurotransmitters are proteins. Many other neurotransmitters, however, are small, hydrophilic (water-loving) organic molecules, including standard amino acids (e.g., glutamate and glycine) (Figure 19) and modified or non-standard amino acids.

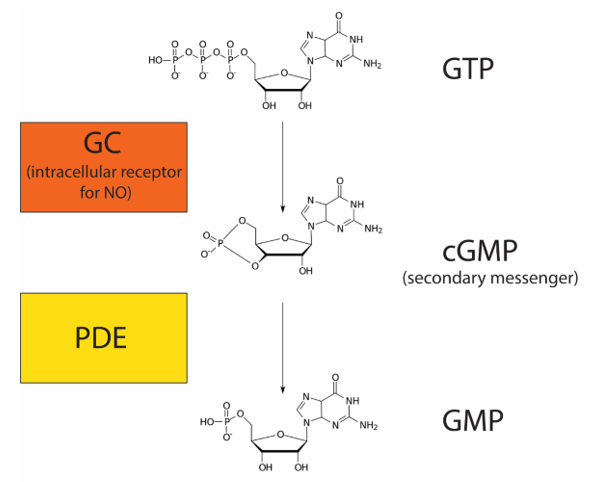

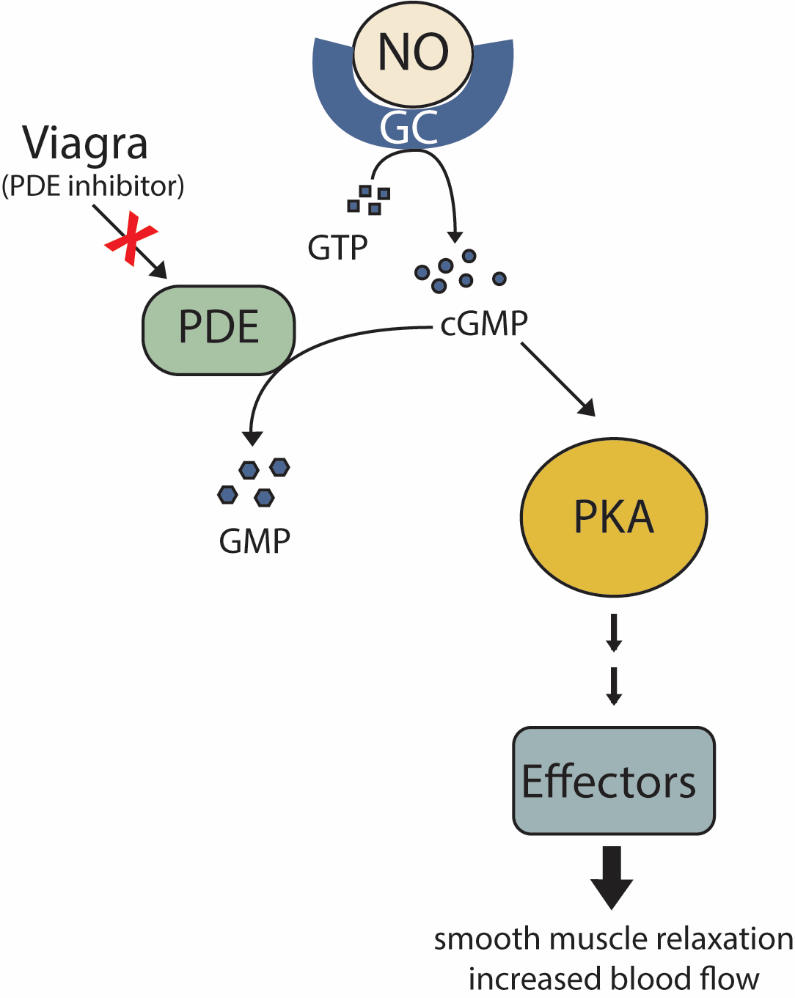

Nitric Oxide Signalling

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gas that can diffuse directly across the plasma membrane. Due to this property, NO, like steroid hormones, can bind to an intracellular receptor. NO plays an important role in regulating blood flow by relaxing smooth muscles around blood vessels (increasing blood flow). In response to neuronal signalling, endothelial cells release NO, which binds to its intracellular receptor, guanylyl cyclase (GC), in adjacent smooth muscle cells. GC is a receptor with enzymatic activity. When bound to its ligand NO, GC metabolizes GTP into cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Figure 20). cGMP is a secondary messenger because it is a small molecule that amplifies the response. Enzymes called phosphodiesterases (PDE) convert cGMP into guanosine monophosphate (GMP).

As secondary messenger cGMP levels rise, cGMP molecules bind to and activate the intracellular signalling molecule protein kinase A to phosphorylate numerous effector proteins, which collectively relax smooth muscles and increase blood flow (Figure 21).

NO has a very short half-life, meaning it only functions over short distances. Nitroglycerin, a treatment for heart disease, acts by triggering the release of NO, which causes blood vessels to dilate (expand), thus restoring blood flow to the heart. NO has become better known recently because prescription medications target the pathway that it affects for erectile dysfunction, such as Viagra (erection involves dilated blood vessels) (Figure 21).

Learning Activity: Summary — Introduction to Cell Signalling

- Visit the “Introduction to Cell Signalling” interactive by LabXchange (2020). Scroll through the interactive. Make your own notes and compare them to your answers from the previous Learning Activities in Unit 4, Topic 1.

- Describe examples of how and why cells use each type of signalling method.

Learning Activity: Mechanisms of Hormone Action

- Watch the video “Mechanisms of Hormone Action” (3:53 min) by Academic Algonquin (2013) and make your own notes. Make sure to integrate the mechanism of action of the two types of hormones with what the Unit 4, Topic 1 readings covered.

- Draw a picture of non-steroid and steroid action mechanisms and summarize the differences.

Key Concepts and Summary

Cells communicate by both inter- and intracellular signalling. Signalling cells secrete ligands that bind to target cells and initiate a chain of events within the target cell. The four categories of signalling in multicellular organisms are paracrine, endocrine, autocrine, and direct across gap junctions. Paracrine signalling takes place over short distances. Endocrine signals are carried long distances through the bloodstream by hormones, and autocrine signals are received by the same cell that sent the signal or other nearby cells of the same kind. Gap junctions allow small molecules, including signalling molecules, to flow between neighbouring cells.

Internal receptors are in the cell cytoplasm. They bind ligand molecules that cross the plasma membrane; these receptor-ligand complexes move to the nucleus and interact directly with cellular DNA. Cell-surface receptors transmit a signal from outside the cell to the cytoplasm. When bound to their ligands, ion channel-linked receptors form a pore through the plasma membrane through which certain ions can pass. G-protein-linked receptors interact with a G-protein on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane, promoting the exchange of bound GDP for GTP and interacting with other enzymes or ion channels to transmit a signal. Enzyme-linked receptors transmit a signal from outside the cell to an intracellular domain of a membrane-bound enzyme. Ligand binding causes activation of the enzyme. Small hydrophobic ligands (like steroids) can penetrate the plasma membrane and bind to internal receptors. Water-soluble hydrophilic ligands are unable to pass through the membrane; instead, they bind to cell-surface receptors, which transmit the signal to the inside of the cell.

Key Terms

autocrine signal

signal that is sent and received by the same or similar nearby cells

cell-surface receptor

cell-surface protein that transmits a signal from the exterior of the cell to the interior, even though the ligand does not enter the cell

chemical synapse

small space between axon terminals and dendrites of nerve cells where neurotransmitters function

dimer

chemical compound formed when two molecules join together

endocrine cell

cell that releases ligands involved in endocrine signalling (hormones)

endocrine signal

long-distance signal that is delivered by ligands (hormones) traveling through an organism’s circulatory system from the signalling cell to the target cell

enzyme-linked receptor

cell-surface receptor with intracellular domains that are associated with membrane-bound enzymes

extracellular domain

region of a cell-surface receptor that is located on the cell surface

G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)

cell-surface receptor that activates membrane-bound G-proteins to transmit a signal from the receptor to nearby membrane components

growth factor

ligand that binds to cell-surface receptors and stimulates cell growth

inhibitor

molecule that binds to a protein (usually an enzyme) and keeps it from functioning

intercellular signalling

communication between cells

internal receptor (also intracellular receptor)

receptor protein that is located in the cytosol of a cell and binds to ligands that pass through the plasma membrane

intracellular mediator (also secondary messenger)

small molecule that transmits signals within a cell

intracellular signalling

communication within cells

ion channel-linked receptor

cell-surface receptor that forms a plasma membrane channel, which opens when a ligand binds to the extracellular domain (ligand-gated channels)

ligand

molecule produced by a signalling cell that binds with a specific receptor, delivering a signal in the process

neurotransmitter

chemical ligand that carries a signal from one nerve cell to the next

paracrine signal

signal between nearby cells that is delivered by ligands traveling in the liquid medium in the space between the cells

phosphatase

enzyme that removes the phosphate group from a molecule that has been previously phosphorylated

receptor

protein in or on a target cell that bind to ligands

secondary messenger

small, non-protein molecule that propagates a signal within the cell after activation of a receptor causes its release

signalling cell

cell that releases signal molecules that allow communication with another cell

signal transduction

propagation of the signal through the cytoplasm (and sometimes also the nucleus) of the cell

synaptic signal

chemical signal (neurotransmitter) that travels between nerve cells

target cell

cell that has a receptor for a signal or ligand from a signalling cell

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Overview of cell signalling [Image 1] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Overview of cell signalling [Image 2] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 11-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 11-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is modified and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 11-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is modified and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 9.3 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 11-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is modified and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Signaling through cell-cell contact [Image 2, modified Figure 42.14 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) under a CC BY 3.0 license] by Khan Academy is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 9.4 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: Figure 11-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: Figure 12-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 11-10 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 11-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: Figure 15.3 by Kindred Grey from Cell Biology, Genetics, and Biochemistry for Pre-Clinical Students (LeClair 2021) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Figure 9.7 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 16: Figure 9.8 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 17: Figure 9.9 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 18: Ligands that bind on the outside of the cell [Image 1] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 19: Ligands that bind on the outside of the cell [Image 2] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 20: Figure 11-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 21: Figure 11-9 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Academic Algonquin. Mechanisms of hormone action [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Aug 16, 3:53 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TgNwxF3aQpE.

Bierema A. 2021. An interactive introduction to organismal and molecular biology. 2nd ed. East Lansing (MI): Michigan State University Library; [accessed 2023 Mar 13]. Chapter 23: cell signaling, Exercises 1 to 4. https://openbooks.lib.msu.edu/isb202/chapter/cell-communication/.

BrainFacts.org. How neurons communicate [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Jan 26, 1:18 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 14]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGDvvUNU-cw.

2 Cao Y, Koh X, Dong L, Du X, Wu A, Ding X, Deng H, Shu Y, Chen J, Jiang T. 2011. Rapid estimation of binding activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin to human and avian receptors. PLOS One. 6(4):e18664. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0018664. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018664.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 11: principles of cell signaling. Figures 11-1, 11-3, 11-5, 11-8 to 11-10, 12-1. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/43283c02-d887-4f2e-a2fa-0ed21e2373be.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Introduction to cell signaling. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. AP®︎/college biology, Lesson 1: cell communication. Figures overview of cell signaling [Image 1, 2], signaling through cell-cell contact [image 2]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-communication-and-cell-cycle/cell-communication/a/introduction-to-cell-signaling.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Ligands & receptors. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Biology library, Lesson 1: how cells signal to each other. Figures ligands that bind on the outside of the cell [images 1, 2].

Khan Academy. Overview of cell signaling [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Nov 5, 8:48 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 13]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQFBygnIONU.

Khanacademymedicine. G protein coupled receptors | nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2014 May 4, 12:47 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 14]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBSo_GFN3qI.

Khanacademymedicine. Enzyme linked receptros | nervous system physology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2014 May 4, 8:50 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kaoRrzakjGE.

Khanacademymedicine. Ligand gated ion channels | nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2014 May 4, 7:21 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 13]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pl7nzXaVqak.

Khanacademymedicine. Membrane receptors | nervous system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2014 May 4, 7:58 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Otn9DVkm-g.

LabXchange. 2020. Introduction to cell signaling [Interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [accessed 2023 Mar 15]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:4400b96e:lx_simulation:1.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figure 15.3. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students/15%3A_Cellular_Signaling/15.01%3A_Cell_communication.

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax).

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 9.1: signaling molecules and cellular receptors. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax)/2%3A_The_Cell/09%3A_Cell_Communication/9.1%3A_Signaling_Molecules_and_Cellular_Receptors.

Pharmacology Animation. Receptors and second messenger system; g-protein, enzyme linked and ligand gated ion channels [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Oct 11, 3:12 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPJG_hy72m8.

QuickSci. Cell signaling in one minutes! autocrine, paracrine, juxtracrine and endocrine signaling | MCAT | [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Aug 17, 1:06 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 14]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-zMkoA7pJk.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 9.1: signaling and molecules and cellular receptors. Figures 9.3, 9.4, 9.7 to 9.9. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/9-1-signaling-molecules-and-cellular-receptors.

1 Sigalov AB. 2010. The SCHOOL of nature: IV. learning from viruses. Self/Nonself. 1(4):282-298. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.4161/self.1.4.13279. doi:10.4161/self.1.4.13279.

Sketchy Medicine. G protein signaling – handwritten cell & molecular biology [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Oct 22, 10:49 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 14]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Bq6qHJaSJs.

Tzbiology. Signal transduction animation [Video]. YouTube. 2011 May 23, 2:32 minutes. [accessed 2023 Mar 14]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FtVb7r8aHco.

propagation of the signal through the cytoplasm (and sometimes also the nucleus) of the cell

communication between cells

communication within cells

cell that releases signal molecules that allow communication with another cell

molecule that binds with specificity to a specific receptor molecule

cell that has a receptor for a signal or ligand from a signaling cell

protein molecule that contains a binding site for another specific molecule (called a ligand)

long-distance signal that is delivered by ligands (hormones) traveling through an organism’s circulatory system from the signaling cell to the target cell

signal between nearby cells that is delivered by ligands traveling in the liquid medium in the space between the cells

signal that is sent and received by the same or similar nearby cells

cell that releases ligands involved in endocrine signaling (hormones)

cell-surface protein that transmits a signal from the exterior of the cell to the interior, even though the ligand does not enter the cell

narrow junction across which a chemical signal passes from neuron to the next, initiating a new electrical signal in the target cell

chemical signal (neurotransmitter) that travels between nerve cells

small molecule that transmits signals within a cell

receptor protein that is located in the cytosol of a cell and binds to ligands that pass through the plasma membrane

small, non-protein molecule that propagates a signal within the cell after activation of a receptor causes its release

cell-surface receptor that forms a plasma membrane channel, which opens when a ligand binds to the extracellular domain (ligand-gated channels)

cell-surface receptor with intracellular domains that are associated with membrane-bound enzymes

chemical ligand that carries a signal from one nerve cell to the next

cell-surface receptor that activates membrane-bound G-proteins to transmit a signal from the receptor to nearby membrane components

region of a cell-surface receptor that is located on the cell surface

a type of extracellular signalling molecule that promotes cell division and survival