4.4 Cancer

Introduction

Does cell cycle control matter? If you ask an oncologist — a doctor who treats cancer patients — they will likely answer with a resounding yes. Cancer is basically a disease of uncontrolled cell division. Its development and progression are usually linked to a series of changes in the activity of cell cycle regulators (see Unit 4, Topic 3). For example, cell cycle inhibitors keep cells from dividing when conditions are incorrect, so too little activity of these inhibitors can promote cancer. Similarly, positive regulators of cell division can lead to cancer if they are too active. In most cases, these changes in activity are due to mutations in the genes that encode cell cycle regulator proteins.

One critical process monitored by the cell cycle checkpoint surveillance mechanism is proper DNA replication during the S phase. Even when all cell cycle controls are fully functional, a small percentage of replication errors (mutations) pass on to the daughter cells. For example, if changes to the DNA nucleotide sequence occur within a coding portion of a gene and are not corrected, a gene mutation results. All cancers start when a gene mutation gives rise to a faulty protein that plays a key role in cell reproduction.

The change in the cell that results from the malformed protein may be minor, perhaps a slight delay in the binding of Cdk to cyclin or an Rb protein that detaches from its target DNA while still phosphorylated (see Unit 4, Topic 3). Even minor mistakes, however, may allow subsequent mistakes to occur more readily. Over and over, small uncorrected errors pass from the parent cell to the daughter cells and amplify as each generation produces more non-functional proteins from uncorrected DNA damage. Eventually, the pace of the cell cycle speeds up as the effectiveness of the control and repair mechanisms decreases. Uncontrolled growth of the mutated cells outpaces the growth of normal cells in the area, and a tumour (“-oma”) can result.

In Unit 4, Topic 4 will cover what is wrong with cancer cells and how abnormal forms of cell cycle regulators can contribute to cancer.

Unit 4, Topic 4 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 4, Topic 4, you will be able to:

- Describe how cancer is caused by uncontrolled cell growth.

- Explain how proto-oncogenes are normal genes that, when mutated, become oncogenes.

- Describe how tumour suppressors function.

- Explain how mutant tumour suppressors cause cancer.

- Describe how changes to gene expression can cause cancer.

| Unit 4, Topic 4—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions from Unit 4, Topic 4 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 40 |

| Complete Learning Activity: What is cancer? | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: DNA Damage and Mutations. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Molecular basis of cancer—changes in DNA underlie cancer. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Hallmarks of cancer I and II. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How telomere length impacts cancer risk. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: The eukaryotic cell cycle and cancer. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Janus kinase. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How does cancer grow? | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell cycle regulators & tumor suppressor genes | proto-oncogenes & oncogenes. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Proto-oncogenes versus tumour suppressor genes. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: The p53 gene and cancer. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Endocrine signalling and breast cancer. | 20 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 4 Quiz. | 7 |

| Go to Moodle and complete the Unit 4 Assignment. | 100 |

What is Wrong with Cancer Cells?

Cancer comprises many different diseases caused by a common mechanism: uncontrolled cell growth. Despite the redundancy and overlapping levels of cell cycle control, errors do occur. One critical process that the cell cycle checkpoint surveillance mechanism monitors is proper DNA replication during the S phase. Even when all cell cycle controls are fully functional, a small percentage of replication errors (mutations) pass on to the daughter cells. If changes to the DNA nucleotide sequence occur within a coding portion of a gene and are not corrected, a gene mutation results. All cancers start when a gene mutation gives rise to a faulty protein that plays a key role in cell reproduction.

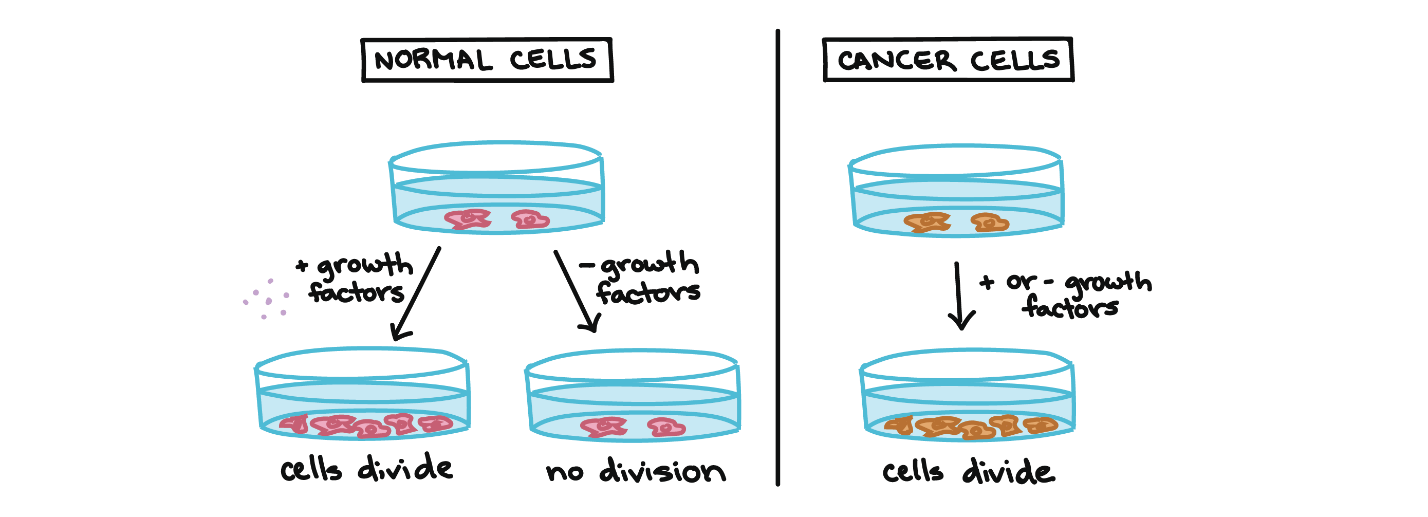

Cancer cells behave differently than normal cells in the body. Many of these differences are related to cell division behaviour. For example, cancer cells can multiply in culture (outside of the body in a dish) without adding any growth factors or growth-stimulating protein signals. This differs from normal cells, which need growth factors to grow in culture (Figure 1). Cancer cells may make their own growth factors, have growth factor pathways stuck in the “on” position, or, in the context of the body, even trick neighbouring cells into producing growth factors to sustain them.1

Cancer cells also ignore signals that should cause them to stop dividing. For instance, when normal cells grown in a dish become crowded by neighbours on all sides, they will no longer divide. Cancer cells, in contrast, keep dividing and pile on top of each other in lumpy layers. The environment in a dish is different from the environment in the human body, but scientists think that the loss of contact inhibition in plate-grown cancer cells reflects the loss of a mechanism that normally maintains tissue balance in the body.1

Another hallmark of cancer cells is their “replicative immortality,” a fancy term for the fact that they can divide many more times than a normal cell of the body. Recall that human cells can generally go through only about 40 to 60 rounds of division before they lose the capacity to divide (see Unit 1, Topic 4), “grow old,” and eventually die.2 Cancer cells can divide many more times than this, largely because they express an enzyme called telomerase, which reverses the wearing down of chromosome ends that normally happens during each cell division1. Most (85 to 90%) cancers express telomerase — at least in the population of cancer stem cells that divide uncontrollably, causing the tumour to grow. Perhaps agents that prevent the expression of the gene for telomerase — or prevent the action of the enzyme — will provide a new class of weapons in the fight against cancer. Treating the cancer this way must be done carefully. If telomerase activity, however brief, is essential for all cells and if lack of telomerase hastens replicative senescence, it may also hasten the aging of the tissues that depend on newly-formed cells for continued health — a trade-off that may not be worth making.

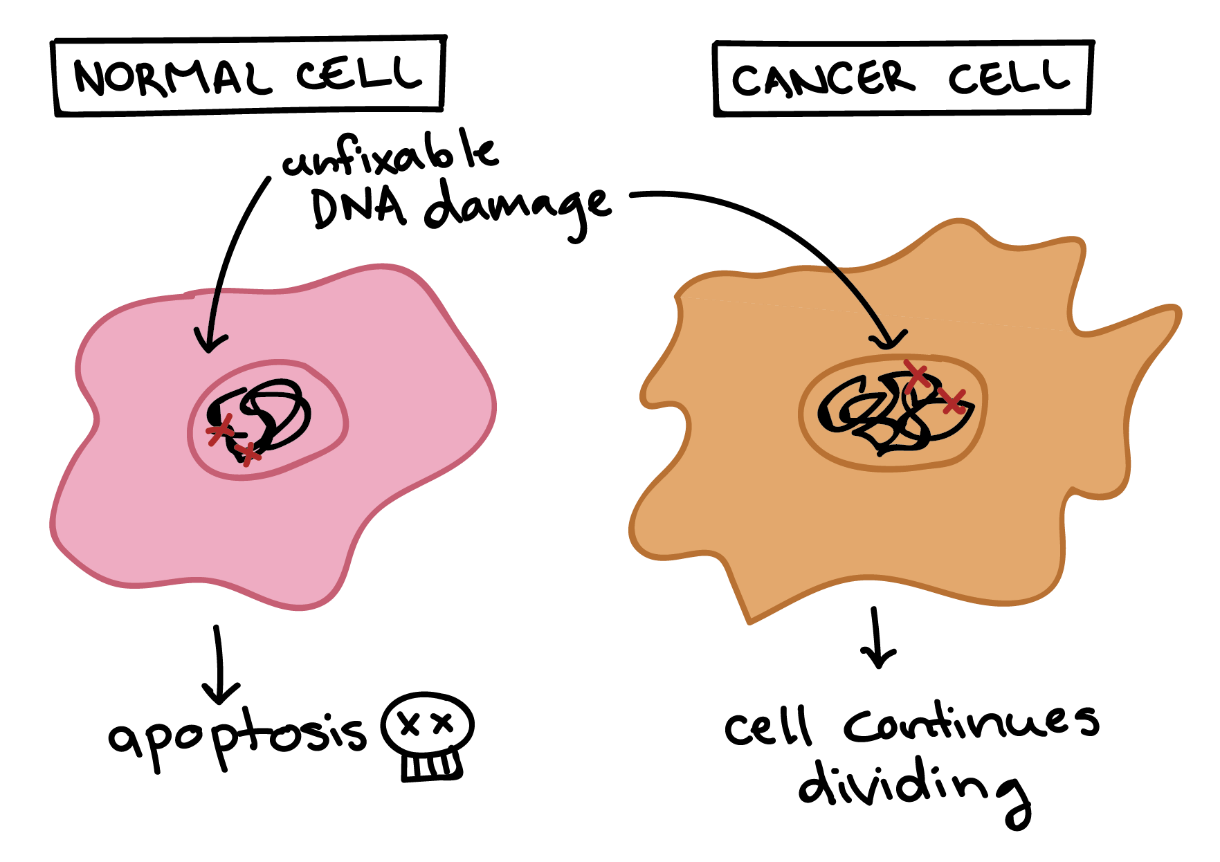

Cancer cells also differ from normal cells in other ways that are not directly related to the cell cycle. These differences help them grow, divide, and form tumours. For instance, cancer cells gain the ability to migrate to other parts of the body, a process called metastasis, and to promote the growth of new blood vessels, a process called angiogenesis (which gives tumour cells a source of oxygen and nutrients). Cancer cells also fail to undergo programmed cell death, or apoptosis, under conditions when normal cells would (e.g., due to DNA damage) (Figure 2). In addition, emerging research shows that cancer cells may undergo metabolic changes that support increased cell growth and division.

Learning Activity: What is Cancer?

- Go to the LabXchange interactive “What is Cancer?” by Lifeology (2020).

- Scroll through all 38 cards by clicking on the arrow at the bottom right of the screen. Make your own notes.

How Cancer Develops

Cells have many different mechanisms to restrict cell division, repair DNA damage, and prevent cancer from developing. Because of this, it is thought that cancer develops in a multi-step process in which multiple mechanisms must fail before reaching a critical mass where cells become cancerous. Specifically, most cancers arise as cells acquire a series of mutations (changes in DNA) that make them divide more quickly, escape internal and external controls on division, and avoid programmed cell death.3 How might this process work? In a hypothetical example, a cell might first lose the activity of a cell cycle inhibitor (see Unit 4, Topic 3), an event that would make the cell’s descendants divide a little more rapidly. These descendants would be unlikely to be cancerous, but they might form a benign tumour, a mass of cells that divides too much but does not have the potential to invade other tissues (metastasize).4

Over time, a mutation might take place in one of the descendant cells, causing increased activity of a positive cell cycle regulator (Figure 3). The mutation might not cause cancer by itself either, but the offspring of this cell would divide even faster, creating a larger pool of cells in which a third mutation could take place. Eventually, one cell might gain enough mutations to take on the characteristics of a cancer cell and give rise to a malignant tumour, a group of cells that divide excessively and can invade other tissues.4

As a tumour progresses, its cells typically acquire more and more mutations. Advanced-stage cancers may have major changes in their genomes, including large-scale mutations such as the loss or duplication of entire chromosomes. How do these changes arise? At least in some cases, they seem to be due to inactivating mutations in the very genes that keep the genome stable — that is, genes that prevent mutations from occurring or being passed on.3

These genes encode proteins that sense and repair DNA damage, intercept DNA-binding chemicals, maintain the telomere caps on the ends of chromosomes, and play other key maintenance roles.1 If one gene mutates and becomes nonfunctional, other mutations can accumulate rapidly. Therefore, if a cell has a nonfunctional genome stability factor, its descendants may reach the critical mass of mutations needed for cancer much faster than normal cells.

DNA Damage and Mutations

- Watch the video “DNA Damage and Mutations | HHMI BioInteractive Video” (1:06 min) by BioInteractive (2018).

- Answer the following questions:

- What are free radicals, and why are they dangerous?

- How does radiation affect DNA?

- How are most of these mutations taken care of?

- What happens if the mutations aren’t corrected?

Learning Activity: Molecular Basis of Cancer — Changes in DNA Underlie Cancer

- Watch the video “3: Molecular basis of cancer part 1: changes in DNA underlie cancer” (7:14 min) by Oncology for Medical Students (2016).

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in Unit 4, Topic 4 and in this video:

- What is the origin of a tumour? How is it propagated from this origin?

- Why is cancer considered to be a genetic disease? Are all cancers passed on to the next generation?

Learning Activity: Hallmarks of Cancer I and II

- Watch the following videos:

- “4. Hallmarks of Cancer (part 1)” by Oncology for Medical Students (9:54 min).

- “5. Hallmarks of cancer (part 2)” (7:19 min) also by Oncology for Medical Students (2016).

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in the video:

- List the six hallmarks of a cancerous cell.

- Do cells require signals to divide? Why do neoplasms result?

- Are there signals that tell a cell not to divide?

- What is metastasis and its relation to the extracellular matrix?

- Why do cancer cells have an unlimited potential to divide?

- What is angiogenesis?

- How do cancer cells avoid apoptosis?

Learning Activity: How Telomere Length Impacts Cancer Risk

- Watch the following videos:

- “How telomere length impacts cancer risk” (3:23 min) by RepeatDx (2021).

- “Telomere Biology Disorders Explained” (4:27 min) also by RepeatDx (2021).

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in the video:

- Describe the Hayflick limit presented in Unit 1, Topic 4.

- How is telomere length associated with an increased risk of cancer?

- Why is long telomere length dangerous for cells?

- Why do some cancers still develop even when they have short telomeres?

- Why do cancer cells need to increase their production of telomerase?

- What are telomere biology disorders (TBDs)? What cancers are associated with TBDs?

- What cancers are long telomeres associated with?

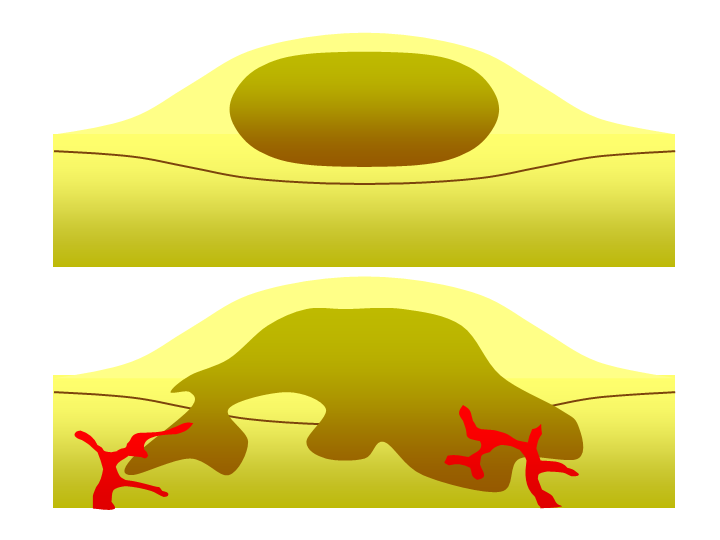

Benign and Malignant Tumours

As previously mentioned, a single mutated cell in a tissue can become the growth point of a tumour, essentially a mass of cells cloned from the original mutated one. Benign tumours or growths are tumours comprised of cells that divide rapidly but are otherwise normal (Figure 4, Top). In some cases, benign tumours stop growing and are not life-threatening. Benign tumours are not considered cancerous; examples of these include breast and uterine fibroids in women or common moles, which can often surgically be removed for the comfort of the patient. In other cases, cells in benign tumours can accrue more mutations and develop into a more dangerous tumour type called a malignant tumour.

Malignant tumours (also called malignant neoplasms) (Figure 4, Bottom) are cancerous and the result of multiple mutations. They can grow beyond the boundaries of the tumour itself. They achieve this by stopping a process called contact inhibition, which refers to contact-dependent signals between adjacent cells within a tissue that prevent cells from growing on top of each other. As tumours grow, they deplete their available nutrients. To continue growing, they release signalling molecules that stimulate the growth and reorganization of nearby blood vessels. The process of blood vessel formation is called angiogenesis (not unique to cancer), which allows the cancer to continue growing by acquiring the necessary nutrients. In addition to providing nutrients, the blood vessels serve as a conduit to travel to a secondary location in the body, the phenomenon called metastasis. Cancer cells that metastasize can become the focal point of new tumour formation in many different tissues. Because cancer cells continue to cycle and replicate their DNA, they can undergo yet more somatic mutations. These further changes can facilitate additional metastasis and cancer cell growth in different locations in the body.

Different cancer cell types have different growth and other behavioural properties. This is what slow-growing and fast-growing cancers refer to. Colon cancers are typically slow-growing, tending to remain in the benign stage longer than other cancers, until an accumulation of mutations results in cancer progression. Periodic colonoscopies that detect and remove colorectal tumours in middle-aged or older people can prevent the disease; however, the patient and doctor must balance the risks of the disease with the procedure. Pancreatic and glial cancers are fast-growing and usually go undetected until they reach an advanced stage. The twin goals of medical research are to detect the different cancers early enough for successful intervention and, of course, to find effective treatments.

Cell Cycle Regulators and Cancer

Cancers accumulate mutations as they mature. Early-stage tumours (benign) can begin with a single mutation, while late-stage tumours (malignant) can have dozens of mutations. Different types of cancer involve different mutations, and each individual tumour has a unique set of genetic alterations. In general, however, mutations of the following two types of cell-cycle regulators may promote the development of cancer:

- Positive regulators may be overactivated (become oncogenic).

- Negative regulators, also called tumour suppressors, may be inactivated.

Learning Activity: The Eukaryotic Cell Cycle and Cancer

- Scroll through the interactive “The Eukaryotic cell cycle and cancer” by BioInteractive (2019).

- Make your own notes including a review of the general cell cycle phases, checkpoints and overview of cell cycle regulators.

Proto-Oncogenes

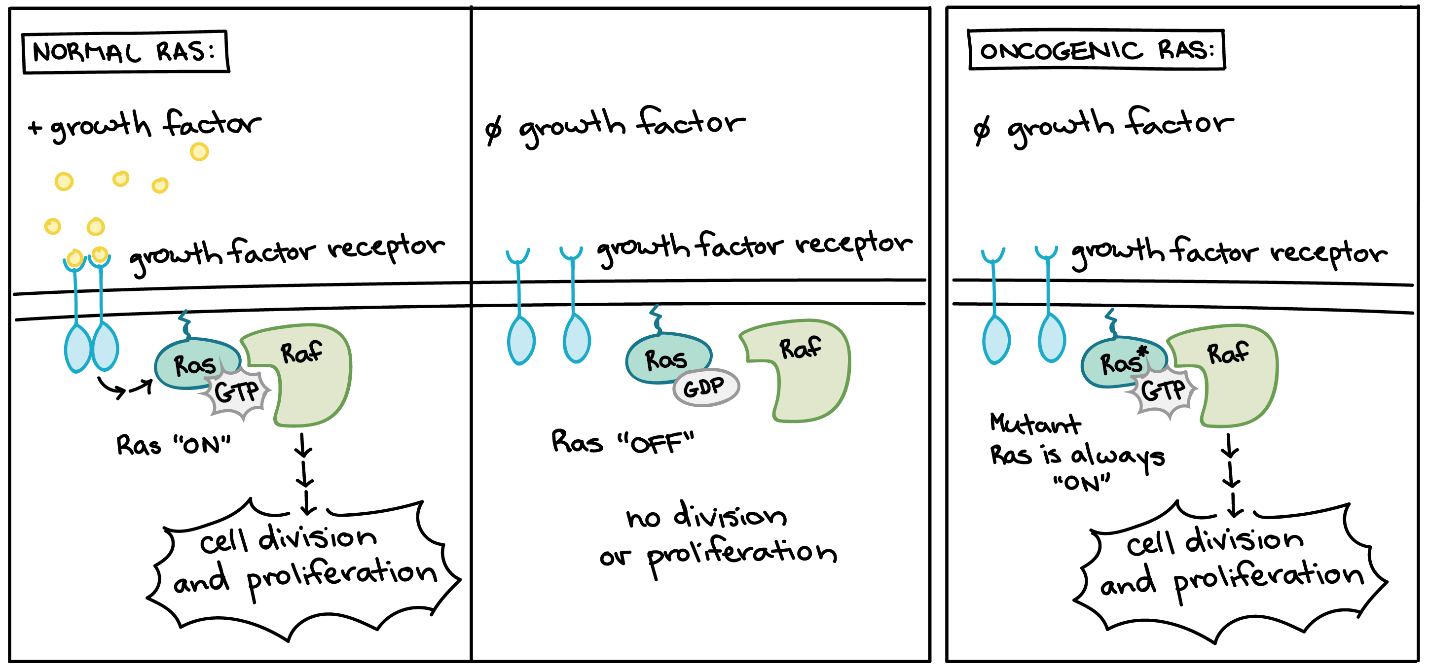

Positive cell-cycle regulators may be overactive in cancer. For instance, a growth factor receptor may send signals without growth factors, or a cyclin may become expressed at abnormally high levels. The overactive (cancer-promoting) forms of these genes are known as oncogenes, while the normal not-yet-mutated forms are called proto-oncogenes. This naming system reflects that a normal proto-oncogene can turn into an oncogene if its mutation increases its activity.

Self-Check

How many gene copies of a proto-oncogene must mutate?

Show/Hide answer.

Humans are diploid, meaning they have two copies (alleles) of most genes in their genome. At the level of the whole organism, mutations that increase a gene’s activity are often dominant, meaning that one mutant allele is enough to produce an effect. That is because one overactive allele and one normal allele still add up to an abnormally high level of activity.

Mutations that convert proto-oncogenes to oncogenes are activating mutations, which increase rather than decrease the activity of a regulator. Thus, these mutations typically have dominant behaviour at the cellular level, producing an effect (in this case, excessive cell division) when just one of a cell’s two gene copies is mutated.

Mutations that turn proto-oncogenes into oncogenes can take different forms. An oncogene is any gene that, when altered, leads to an increase in the rate of cell cycle progression. Some change the protein’s amino acid sequence, altering its shape and trapping it in an “always on” state. Others involve amplification, in which a cell gains extra copies of a gene and thus starts making too much protein. In other cases, an error in DNA repair may attach a proto-oncogene to part of a different gene, producing a “combo” protein with unregulated activity.5

Example 1: Cell Cycle Regulatory Proteins

Consider what might happen to the cell cycle in a cell with a recently acquired oncogene. In some or most instances, altering the DNA sequence results in a less functional (or non-functional) protein. This change is detrimental to the cell and likely prevents it from completing the cell cycle; however, it does not harm the organism because the mutation does not carry forward. If a cell cannot reproduce, the mutation does not propagate, and the damage is minimal. Occasionally, however, a gene mutation causes a change that increases the activity of a positive regulator. For example, a mutation that allows Cdk to activate without being partnered with cyclin (see Unit 4, Topic 3) can push the cell cycle past a checkpoint before meeting all required conditions. If the resulting daughter cells are too damaged to undergo further cell divisions, the mutation does not propagate, and no harm comes to the organism. However, if the atypical daughter cells can undergo further cell divisions, subsequent generations of cells may accumulate even more mutations, some possibly in additional genes that regulate the cell cycle.

Example 2: Growth Factors

In addition to the cell cycle regulatory proteins, any protein that influences the cycle can be altered in such a way as to override cell cycle checkpoints. Unsurprisingly, many genes that help initiate the pro-growth MAPK signalling pathway are proto-oncogenes. Examples include the Ras GTPase, EGFR (epithelial growth factor receptor, a receptor tyrosine kinase), and Her2 (another receptor kinase frequently mutated in breast cancers) (see Unit 4, Topic 2).

Proto-oncogenes encode many proteins that transmit growth factor signals (Figure 5). These proteins usually drive cell cycle progression only when growth factors are available. However, if one of the proteins becomes overactive due to mutation, it may transmit signals even with no growth factor around.6

Mutations in genes that promote apoptosis in Drosophila embryos result in the prolonged survival of cells that would die as a normal process of central nervous system (CNS) development.7 Conversely, overexpression of such genes can induce inappropriate cell death.8 In contrast, increasing and/or prolonging the exposure of CNS cells to EGFR signalling can promote cell survival in the developing CNS of Drosophila embryos.7,9 Overactive forms of these proteins are often found in cancer cells. For instance, oncogenic Ras mutations are found in approximately 90% of pancreatic cancers. Ras is a G protein, meaning that it switches back and forth between an inactive form (bound to GDP) and an active form (bound to GTP) (see Unit 4, Topic 2). Cancer-causing mutations often change Ras’s structure so that it can no longer switch to its inactive form or do so only very slowly, leaving the protein stuck in the “on” state (Figure 5).10

Learning Activity: Janus Kinase

- Read the news article “After more than 20 years, scientists have solved the full-length structure of a Janus kinase” by Jim Keeley (2022) from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, where researchers describe their hunt for the 3D structure of an important cell signalling molecule called Janus kinase.

- Answer the following questions:

- Draw a diagram illustrating how Garcia describes Janus kinase proteins signal through their receptors in a normal cell. Does this remind you of a similar signalling mechanism discussed in Unit 4?

- Now, draw a new diagram to illustrate what happens to the signalling process when Janus kinase has a gain-of-function, cancer-causing mutation.

- Explain why it was so important to find the 3D structure of the mutant Janus kinases when they already had the 3D structure of the normal proteins.

Tumour Suppressors

Negative regulators of the cell cycle may be less active (or even nonfunctional) in cancer cells. For instance, a protein that halts cell cycle progression in response to DNA damage may no longer sense damage or trigger a response. Genes that usually block cell cycle progression are known as tumour suppressors. Tumour suppressors prevent cancerous tumours from forming when they are working correctly; because of this, tumours may form when they mutate, so they no longer work.

Self-Check

How many gene copies of a tumour suppressor must mutate?

Show/Hide answer.

Humans are diploid, meaning they have two copies (alleles) of most genes in their genome. At the organismal level, mutations that reduce or eliminate a gene’s function are typically recessive, meaning both alleles must have the mutation to see an effect. The reason is that one “good” allele can compensate for a nonfunctional mutant allele.

The mutations that inactivate tumour suppressors are loss-of-function mutations; they decrease or eliminate the activity of a regulator. Thus, inactivating mutations in tumour suppressors typically behave in a recessive manner at the cellular level, producing an effect (in this case, too much cell division) only when both gene copies in a cell have mutations.

How can both copies of a tumour suppressor gene acquire mutations?

Two spontaneous mutations affecting the two different alleles may occur in the same cell over time. A person may inherit one “bad” allele of the tumour suppressor from a parent, then lose activity of the other allele through a spontaneous mutation.

People who inherit one “bad” allele from a parent — and thus are down to just one functional allele in all the cells of the body — are much more prone to cancer than people who inherit two normal alleles.

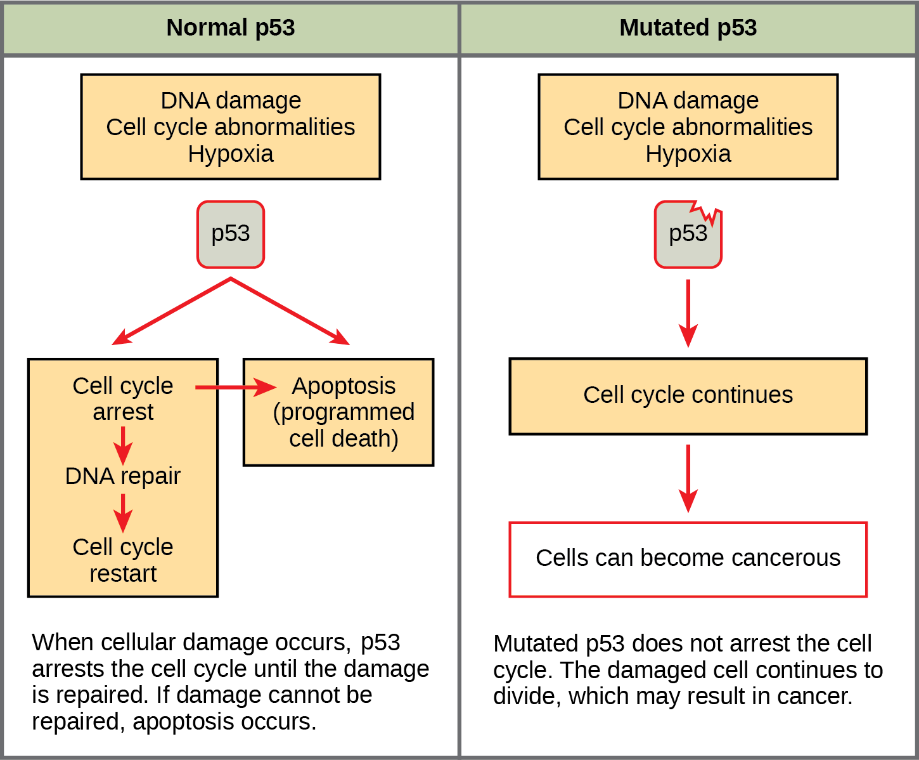

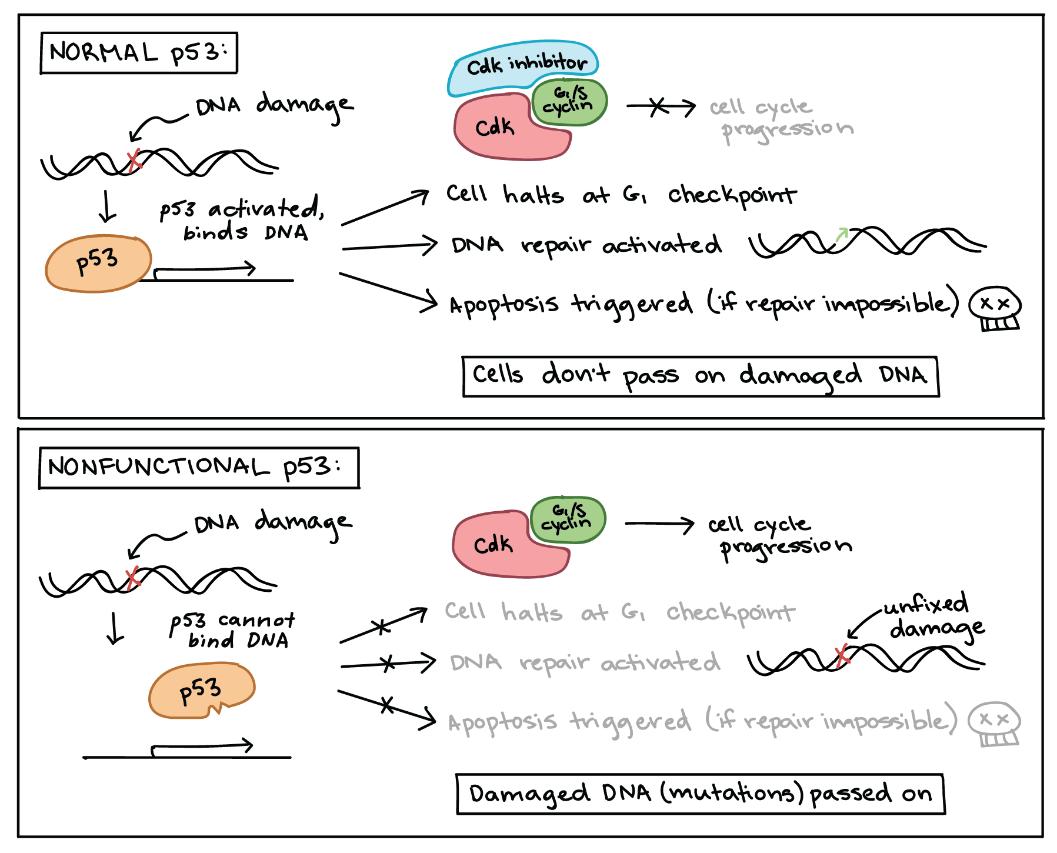

p53 is one of the most important tumour suppressors that plays a key role in the cellular response to DNA damage (Figure 6). p53 acts primarily at the G1 checkpoint (controlling the G1 to S transition), where it blocks cell cycle progression in response to damaged DNA and other unfavourable conditions.11

As discussed in Unit 4, Topic 3, when a cell’s DNA is damaged, a sensor protein activates p53, triggering the production of a cell cycle inhibitor to halt the cell cycle at the G1 checkpoint. This pause provides time for DNA repair, which also depends on p53, whose second job is to activate DNA repair enzymes. If these enzymes fix the damage, p53 releases the cell, allowing it to continue through the cell cycle. If these enzymes cannot fix the damage, p53 plays its third and final role: triggering apoptosis (programmed cell death) so that damaged DNA does not pass on.

In cancer cells, p53 is often missing, nonfunctional, or less active than normal. For example, many cancerous tumours have a mutant form of p53 that can no longer bind DNA. Since p53 acts by binding to target genes and activating their transcription, the non-binding mutant protein is unable to do its job (Figure 7).12

When p53 is defective, a cell with damaged DNA may proceed with cell division. The daughter cells of such a division are likely to inherit mutations due to the unrepaired DNA in the mother cell. Over generations, cells with faulty p53 tend to accumulate mutations, some of which may turn proto-oncogenes to oncogenes or inactivate other tumour suppressors.

Learning Activity: How Does Cancer Grow?

- Scroll through the LabXchange interactive “How Does Cancer Grow?” by Lifeology (2020).

- Make your own notes before proceeding to the next Learning Activities.

Learning Activity: Cell Cycle Regulators & Tumour Suppressor Genes | Proto-Oncogenes & Oncogenes

- Watch the following videos:

- “Cell Cycle Regulators & Tumor Suppressor Genes | Proto-oncogenes & Oncogenes” (9:57 min) by Catalyst University (2021).

- “How a Proto Oncogene Becomes an Oncogene” (0:41 min) by Bioreply (2009).

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in Unit 4, Topic 4 and in these videos:

- Explain the difference between a proto-oncogene and an oncogene. What type of a cell cycle regulator is a proto-oncogene? How does a mutation in a positive cell cycle regulator affect the cell cycle?

- What do tumour suppressors typically do within the cell?

- What are two ways in which a proto-oncogene can become an oncogene?

Learning Activity: Proto-Oncogenes Versus Tumour Suppressor Genes

- Watch the following videos and make your own notes:

- “Role of cancer genes” (2:49 min) by Yourgenome (2014).

- “6. Tumour Suppressor Genes (Retinoblastoma and the two hit hypothesis, p53)” (10:27 min) by Oncology for Medical Students (2016).

- “7. Proto-oncogenes and Oncogenes” (5:22 min) by Oncology for Medical Students (2016).

- Answer the following questions:

- What types of mutations typically occur in tumour suppressor genes to misregulate the cell cycle? How many of the gene copies need to be mutated to affect the cell cycle in diploid organisms? Why?

- What is the normal function of Rb in the cell cycle? Why is it considered a tumour suppressor? Which checkpoint do recessive Rb mutations affect?

- Describe the two-hit hypothesis in reference to Rb.

- What is another tumour suppressor that is important in cancer? What two cell cycle processes does it normally regulate?

- Why are oncogenes like the accelerator pedal of a car?

- What is the most commonly mutated proto-oncogene? What happens to it when mutated?

Learning Activity: The P53 Gene and Cancer

- Scroll through the interactive “The p53 gene and cancer” by BioInteractive (2003). Make your own notes.

- Answer the following questions:

- Does p53 directly or indirectly regulate its target genes? How is p53 able to interact with DNA?

- What is Mdm2, and how does it regulate p53?

- In what processes do p53 target genes function?

Learning Activity: Endocrine Signalling and Breast Cancer

- Scroll through this interactive “Endocrine Signaling and Breast Cancer” by LabXchange (2021).

- Answer the following questions:

- How does estrogen signalling differ from Janus kinase signalling?

- What is the name of the domain used by estrogen to bind its receptor? What happens after estrogen binds to this domain?

- What part of the receptor-estrogen complex actually binds to DNA? What is the name of this DNA sequence?

- What is the name of genes activated by the complex?

- What domains bind the coactivator after the complex has bound to DNA?

- What is the role of the coactivator?

- How does estrogen-mediated gene regulation differ from that of p53?

- What cellular processes are activated by the estrogen-responsive genes?

- What type of cancer results from abnormal estrogen signalling?

- How can a knowledge of estrogen molecules be used to treat breast cancer resulting from too much estrogen signalling?

- Researchers have been using tamoxifen to treat breast cancer. What happens when tamoxifen binds the estrogen receptor instead of estrogen?

- How does tamoxifen inhibit cancer?

Key Concepts and Summary

Cancer is the result of unchecked cell division caused by a breakdown of the mechanisms that regulate the cell cycle. The loss of control begins with a change in the DNA sequence of a gene that codes for one of the regulatory molecules. Faulty instructions lead to a protein that does not function as it should. Any disruption of the monitoring system can allow other mistakes to pass on to the daughter cells. Each successive cell division will give rise to daughter cells with even more accumulated damage. Eventually, all checkpoints become nonfunctional, and rapidly reproducing cells crowd out normal cells, resulting in a tumour or leukemia (blood cancer).

Proto-oncogenes:

- Proto-oncogenes positively regulate the cell cycle.

- Mutations may cause proto-oncogenes to become oncogenes, disrupting normal cell division and causing cancers to form.

- Some mutations prevent the cell from reproducing, which keeps the mutations from being passed on.

- If a mutated cell is able to reproduce because the cell division regulators are damaged, then the mutation will be passed on, possibly accumulating more mutations with successive divisions.

Tumour suppressor genes:

- Tumor suppressor genes are segments of DNA that code for negative regulator proteins, which keep the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division.

- Mutated p53 genes are believed to be responsible for causing tumour growth because they turn off the regulatory mechanisms that keep cells from dividing out of control.

- Sometimes cells with negative regulators can halt their transmission by inducing pre-programmed cell death called apoptosis.

- Without a fully functional p53, the G1 checkpoint of interphase is severely compromised, and the cell proceeds directly from G1 to S; this creates two daughter cells that have inherited the mutated p53 gene.

Quiz

Complete the Unit 4 Quiz found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Assignment

Complete the Unit 4 Assignment found in the Assessments Overview section in Moodle.

Key Terms

acute lymphocytic leukemia

a type of leukemia (blood cancer) that comes on quickly and is fast growing. In acute lymphocytic leukemia, there are too many lymphoblasts (immature white blood cells) in the blood and bone marrow. Also called acute lymphoblastic leukemia and ALL

benign

not cancer. Benign tumours may grow larger but do not spread to other parts of the body; also called nonmalignant

cancer

a population of cells that grows uncontrollably and can invade neighbouring tissues

chronic myelogenous leukemia

an indolent (slow-growing) cancer in which too many myeloblasts are found in the blood and bone marrow. Myeloblasts are a type of immature blood cell that makes white blood cells called myeloid cells. Chronic myelogenous leukemia may get worse over time as the number of myeloblasts increases in the blood and bone marrow. This may cause fever, fatigue, easy bleeding, anemia, infection, a swollen spleen, bone pain, or other signs and symptoms. Chronic myelogenous leukemia is usually marked by a chromosome change called the Philadelphia chromosome, in which a piece of chromosome 9 and a piece of chromosome 22 break off and trade places with each other. It usually occurs in older adults and rarely occurs in children. Also called chronic granulocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, and CML

coactivator

proteins that connect activators with the gene targets they regulate

DNA-binding domain

a protein sequence in a transcription factor that binds to a target DNA sequence

epidermal growth factor receptor

a tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptor that stimulates growth and division of cells once bound by the epidermal growth factor

gatekeeper gene

tumour suppressor gene that halts cell proliferation; loss-of-function mutations are associated with excessive cell proliferation and tumour formation

genetic instability

the accumulation of multiple mutations in cancer cells caused by defects in DNA repair genes or chromosome sorting processes

Janus kinase

a cytoplasmic protein kinase that is activated by receptor binding and catalyzes the phosphorylation of STAT transcription factors

leukemia

cancer that starts in blood-forming tissue, such as the bone marrow, and causes large numbers of abnormal blood cells to be produced and enter the bloodstream

metastasis

the spread of cancer cells through the blood or lymph system from their origin to a secondary site in an organism

mutation

any heritable change of the base-pair sequence of genetic material

oncogene

a mutated version of a proto-oncogene, which allows for uncontrolled progression of the cell cycle, or uncontrolled cell reproduction

proto-oncogene

a normal gene that controls cell division by regulating the cell cycle that becomes an oncogene if it is mutated

tumour suppressor gene

a gene that codes for regulator proteins that prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division

Long Descriptions

Figure 3 Image Description: The initial cell mutation inactivates a negative cell cycle regulator. The next mutation overactivates a positive cell cycle regulator. The third mutation inactivates a genome stability factor. Additional mutations accumulate rapidly, leading to a cancer cell. [Return to Figure 3]

Figure 7 Image Description: In normal p53, DNA damage activates p53 that binds to the DNA. This binding halts the cell cycle at the G1 checkpoint, activates DNA repair, and activates apoptosis if repair is impossible. Normal p53 ensures cells do not pass on damaged DNA. In nonfunctional p53, p53 cannot bind to damaged DNA. This means that p53 cannot repair the DNA damage, and this damaged DNA (mutations) passes on. [Return to Figure 7]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: What’s wrong with cancer cells? [Image 1] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: What’s wrong with cancer cells? [Image 2] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: How cancer develops by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 15-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Oncogenes by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 10.14 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Tumor suppressors by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

2 Bartlett Z. 2014. The Hayflick Limit. Tempe (AZ): Arizona State University; [updated 2023 Sep 11; accessed 2024 Jan 23]. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/hayflick-limit.

BioInteractive. 2003. The p53 gene and cancer [interactive simulation]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [updated 2020 Apr 30; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.biointeractive.org/classroom-resources/p53-gene-and-cancer.

BioInteractive. DNA damage and mutations | HHMI BioInteractive video [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Nov 29, 1:06 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfPeSnJhVsw.

BioInteractive. 2019. The eukaryotic cell cycle and cancer [interactive simulation]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [updated 2019 Mar 27; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://media.hhmi.org/biointeractive/click/cellcycle/.

Bioreply. How a proto oncogene becomes an oncogene [Video]. YouTube. 2009 Feb 9, 0:41 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2wIVwZksIt4.

Catalyst University. Cell cycle regulators & tumor suppressor genes | proto-oncogenes & oncogenes [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Apr 16, 9:57 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckxDMDU9Jxg.

1 Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 144(5):646-674. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867411001279?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Figure 15-8. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/db353ee7-8050-4d91-b3e7-2ed8ce59e5e7.

Keeley J. 2022. After more than 20 years, scientists have solved the full-length structure of a Janus kinase [news article]. Chevy Chase (MD): Howard Hughes Medical Institute; [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.hhmi.org/news/after-more-20-years-scientists-have-solved-full-length-structure-janus-kinase.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. Cancer and the cell cycle. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures what’s wrong with cancer cells? [Image 1, 2], how cancer develops, oncogenes, tumor suppressors. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-communication-and-cell-cycle/regulation-of-cell-cycle/a/cancer.

LabXchange. 2021. Endocrine signaling and breast cancer [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 May 30; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:a1520d4f:lx_simulation:1.

Lifeology. 2020. How does cancer grow? [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 Jun 29; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:cb6185cf:lx_simulation:1.

Lifeology. 2020. What is cancer? [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [updated 2023 Jun 29; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:f33d813e:lx_simulation:1.

5 Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J. 2000. Molecular cell biology. 4th ed. New York (NY): W. H. Freeman. Section 24.2: proto-oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes.

Molnar C, Gair J. 2019. Concepts of biology – H5P. Victoria (BC): BCcampus. [accessed 2024 Jan 23]. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/biologyh5p/.

Molnar C, Gair J. 2019. Concepts of biology – H5P. Victoria (BC): BCcampus. [accessed 2024 Jan 23]. Chapter 6.3: cancer and the cell cycle. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/biologyh5p/chapter/6-3-cancer-and-the-cell-cycle/.

Oncology for Medical Students. 3. molecular basis of cancer part 1: changes in DNA underlie cancer [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Mar 10, 7:14 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KsMTDr9rG8o.

Oncology for Medical Students. 4. hallmarks of cancer (part 1) [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Apr 16, 9:54 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ea-CALtn7hA.

Oncology for Medical Students. 5. hallmarks of cancer (part 2) [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Apr 17, 7:19 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSD0ZwfZ2BU.

Oncology for Medical Students. 6. tumour suppressor genes (retinoblastoma and the two hit hypothesis, p53) [Video]. YouTube. 2016 May 2, 10:27 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-Njz_iSvLI.

Oncology for Medical Students. 7. Proto-oncogenes and oncogenes [Video]. YouTube. 2016 May 8, 5:22 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9J8cMW94VUs.

11 Raven PH, Johnson GB, Mason KA, Losos JB, Singer SR. 2013. Biology. 10th ed., AP ed. New York (NY): McGraw Hill. Cancer is a failure of cell cycle control; p. 202-204.

4 Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB. 2019. Campbell biology. 10th ed. London (England): Pearson. The cell cycle; p. 247.

RepeatDx. How telomere length impacts cancer risk [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Nov 24, 3:23 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aM5Pl53zMg.

RepeatDx. Telomere biology disorders explained [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Nov 24, 4:27 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVTd0ZkTH3k.

6 Roberts PJ, Der CJ. 2007. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 26:3291-3310. https://www.nature.com/articles/1210422. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210422.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 10.4: cancer and the cell cycle. Figure 10.14. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/10-4-cancer-and-the-cell-cycle.

10 Santarpia L, Lippman SM, El-Naggar AK. 2012. Targeting the MAPK–RAS–RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 16(1):103-119. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1517/14728222.2011.645805. doi:10.1517/14728222.2011.645805.

9 Sonnenfeld MJ, Barazesh N, Sedaghat Y, Fan C. 2004. The jing and ras1 pathways are functionally related during CNS midline and tracheal development. Mech Dev. 121(12):1531-1547. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925477304001923?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2004.07.006.

7 Sonnenfeld MJ, Jacobs JR. 1995. Apoptosis of the midline glia during Drosophila embryogenesis: a correlation with axon contact. Development. 121(2):569-578. https://journals.biologists.com/dev/article/121/2/569/38762/Apoptosis-of-the-midline-glia-during-Drosophila. doi:10.1242/dev.121.2.569.

3 Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. 2004. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 10:789-799. https://www.nature.com/articles/nm1087. doi:10.1038/nm1087.

13 Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. 2000. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 408:307-310. https://www.nature.com/articles/35042675. doi:10.1038/35042675.

12 Vogelstein B, Sur S, Prives C. 2010. p53: the most frequently altered gene in human cancers. Nat Educ. [accessed 2024 Jan 23];3(9):6. https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/p53-the-most-frequently-altered-gene-in-14192717/.

8 White K, Tahaoglu E, Steller H. 1996. Cell killing by the Drosophila gene reaper. Science. 271(5250):805-807. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.271.5250.805. doi:10.1126/science.271.5250.805.

Yourgenome. Role of cancer genes [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Dec 19, 2:49 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4Ul9LaYg_w.

a population of cells that grows uncontrollably and can invade neighbouring tissues

any heritable change of the base-pair sequence of genetic material

the spread of cancer cells through the blood or lymph system from their origin to a secondary site in an organism

not cancer. Benign tumours may grow larger but do not spread to other parts of the body; also called nonmalignant

a mutated version of a proto-oncogene, which allows for uncontrolled progression of the cell cycle, or uncontrolled cell reproduction

a normal gene that controls cell division by regulating the cell cycle that becomes an oncogene if it is mutated

a tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptor that stimulates growth and division of cells once bound by the epidermal growth factor

a cytoplasmic protein kinase that is activated by receptor binding and catalyzes the phosphorylation of STAT transcription factors

a gene that codes for regulator proteins that prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division

a protein sequence in a transcription factor that binds to a target DNA sequence

proteins that connect activators with the gene targets they regulate

cancer that starts in blood-forming tissue, such as the bone marrow, and causes large numbers of abnormal blood cells to be produced and enter the bloodstream