3.2 The Endomembrane System I — The Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus

Introduction

Imagine you are a pancreatic cell. Your job is to secrete the digestive enzymes that travel into the small intestine and help break down food into nutrients. To carry out this job, you somehow have to get those enzymes shipped from their site of synthesis — inside the cell — to their place of action — outside the cell.

How are you going to make this happen? After a moment of panic in which you consider calling the postal service, you relax, having remembered: I have an endomembrane system!

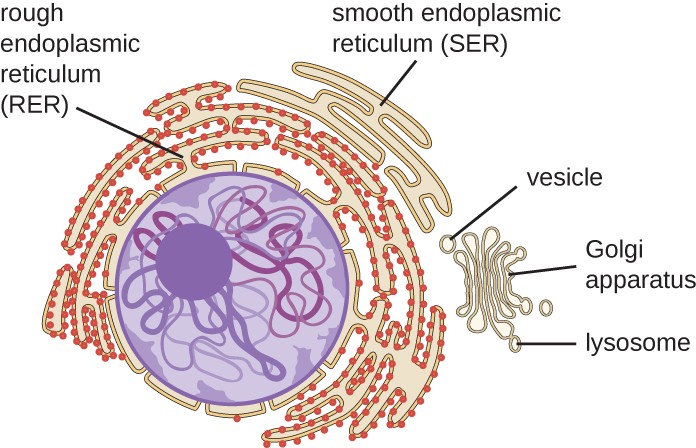

The endomembrane system (endo = within), unique to eukaryotic cells, is a series of membranous tubules, sacs, and flattened disks that synthesize many cell components and move materials around within the cell. Recall from Unit 1 that because of their larger cell size, eukaryotic cells require compartmentalization to transport materials unable to disperse by diffusion alone. The endomembrane system comprises several organelles and connections between them, including the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and vesicles. These cellular components work together to modify, package, and transport lipids and proteins. Although the plasma membrane is not technically within the cell, it is included in the endomembrane system because, as you will see, it interacts with the other endomembranous organelles.

Unit 3, Topic 2 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 3, Topic 2, you will be able to:

- List and identify the components of the endomembrane system.

- Explain how internal membranes and organelles contribute to compartmentalization and maintain proper cellular functions.

- Diagram the mechanism by which proteins are transported between different cellular compartments.

- Describe the synthesis of glycoproteins/glycolipids and the topology of their carbohydrate side chains.

| Unit 3, Topic 2—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 3, Topic 2 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Structures. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Chaperonin-Assisted Protein Folding. | 2 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Chaperones and misfolded proteins. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Vesicular Flow. | 25 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Glycosylation and Glycoproteins. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Glycosylation and ABO Blood Types. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Glycoprotein topology. | 5 |

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an interconnected array of tubules and cisternae (flattened sacs) with a single lipid bilayer that extends throughout the cytoplasm of almost every eukaryotic cell (Figure 1). The spaces inside the cisternae are called the lumen of the ER. There are two types of ER, rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER). These two ER types are sites for synthesizing different types of molecules.

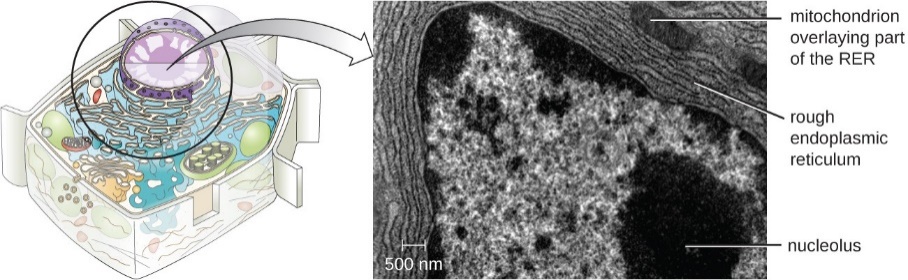

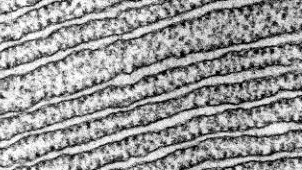

The RER is continuous with the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope. It appears rough under an electron microscope because of the ribosomes bound on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane studding it (Figure 2). As mentioned previously, the protein synthesis on ribosomes attached to the ER (cotranslation) results in transferring their newly synthesized proteins into the lumen or membrane of the RER. In the lumen, such proteins can undergo modifications such as folding or adding sugars (glycosylation). Nearly all RER-synthesized proteins glycosylate with short-branched oligosaccharides. This glycosylation occurs in an N-linked fashion on asparagine residues (discussed further below). The RER also makes phospholipids for cell membranes. Therefore, the RER membrane retains transmembrane proteins or phospholipids destined for the plasma membrane or the membrane of organelles.

Figure 2: (Left) The RER is studded with ribosomes for the synthesis of membrane proteins (resulting in its rough appearance). (Right) A higher magnification electron micrograph (courtesy of Keith Porter) of the RER in a bat pancreas cell. The clearer areas are the lumens. (Parker et al. 2016/Microbiology/OpenStax) CC BY 4.0

The SER does not have ribosomes; therefore, it appears “smooth” by electron microscopy. It is continuous with the RER but differs from the RER by lacking attached ribosomes and usually having a tubular shape rather than disc-like. The SER’s functions include synthesizing carbohydrates, lipids (including phospholipids), and steroid hormones, detoxifying medications and poisons, metabolizing alcohol, and storing calcium ions. The SER is a prominent constituent of some cells, especially the cells in the adrenal cortex (which secrete steroid hormones), the cells of the liver (hepatocytes), where it makes lipids for secretion of lipoproteins, and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of muscle cells.

Learning Activity: Structures

Watch the following videos. Make your own notes.

- “Endoplasmic Reticulum” (2:02 min) by Learnbiologically (2013).

- “Intracellular Organelles- Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum (RER)” (7:30 min) by Medic Tutorials – Medicine and Language (2015).

Protein Folding in the Endoplasmic Reticulum

The ER lumen plays the following four major protein processing roles:

- Polypeptide folding/refolding

- Protein glycosylation

- Multi-subunit protein assembly

- Packaging proteins into vesicles

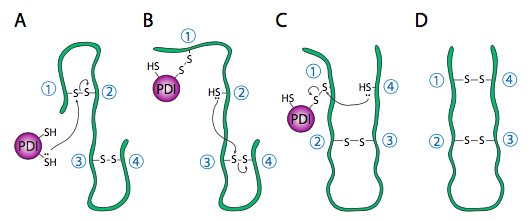

Refolding proteins is an important process because the initial folding patterns, as the polypeptide is still translating and unfinished, may not be optimal once the entire protein is available. Not only is this true for H-bonds, but it is also true for more permanent (i.e., covalent) disulfide bonds. Looking at the hypothetical example polypeptide, the secondary structure of the N-terminal half may form a stable disulfide bond between the first cysteine and the second cysteine; however, in the context of the whole protein, a more stable disulfide bond may form between cysteine 1 and cysteine 4. The protein disulfide isomerase family of enzymes catalyzes the exchange of disulfide bonding targets (Figure 3).

Disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in a polypeptide contribute to the protein’s tertiary structure. Oxidizing environments promote disulfide bond formation, but reducing environments favour dissociating disulfide bonds into free thiol (also called sulfhydryl, -SH) groups. The internal redox environment of the ER is significantly more oxidative than that in the cytoplasm, mainly determined by the ratio of glutathione (GSH) to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). GSH is a reducing agent that oxidizes to GSSG. High GSH concentrations promote reduction. The GSH:GSSG ratio is 30:1 in the cytoplasm and nearly 1:1 in the ER lumen, meaning that the cytoplasm is more reducing than the ER lumen. Conversely, the ER lumen is more oxidative than the cytoplasm. This oxidative environment is also conducive to disulfide remodelling. Note that protein disulfide isomerase does not choose the “correct” bonding partners. It simply moves the existing disulfide bonds to a more energetically stable arrangement. As the rest of the polypeptide continues to refold, break and make disulfide bonds quickly, new potential disulfide bonding partners may move near one another. This movement allows protein disulfide isomerase to attempt to rearrange the disulfide bonding pattern if the resulting pattern is more thermodynamically stable (Figure 4).

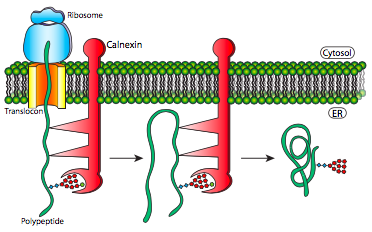

Multi-subunit protein assembly and polypeptide refolding are similar because both use chaperone proteins to help prevent premature folding, sequestering parts of the protein from H-bonding interaction until the completed protein is in the ER lumen (Figure 5).

This mechanism makes finding the thermodynamically optimal conformation easier by preventing some potential suboptimal conformations from forming. These chaperone proteins bind to new proteins as they enter the lumen through the translocon. In addition to simply preventing incorrect bonds that would have to be broken, they also prevent premature interaction of multiple polypeptides with one another. This problem can occur when immature polypeptides have not undergone proper folding that would usually hide their interaction domains within the protein; exposed interaction domains can lead to indiscriminate binding and potentially precipitating insoluble protein aggregates.

Chaperones

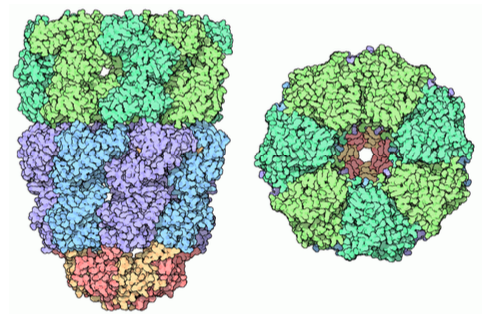

Chaperone proteins can be found in prokaryotes, archaea, and the cytoplasm of eukaryotes. These are somewhat similar and function somewhat differently than the types of folding proteins found in the ER lumen. They are referred to generally as chaperonins; the most well-known is the GroEL/ GroES complex in E. coli. As the structure in Figure 6 indicates, it is similar in shape to the proteasome, although with a completely different function. GroEL consists of two stacked rings, each composed of seven subunits, with a large central cavity and a large area of hydrophobic residues at its opening. GroES is also composed of seven subunits and acts as a cap on one end of the GroEL. However, GroES only caps GroEL in the presence of ATP. Upon hydrolysis of the ATP, the chaperonins undergo signficant concerted conformational changes that impinge on the protein inside, causing refolding, and then the GroES dissociates, and the protein is released back into the cytosol.

Learning Activity: Chaperonin-Assisted Protein Folding

- Watch the video “Active Cage Mechanism of Chaperonin-Assisted Protein Folding Demonstrated at Single-Molecule Level” (1:37 min) by Rachel Davidowitz (2014). Make your own notes.

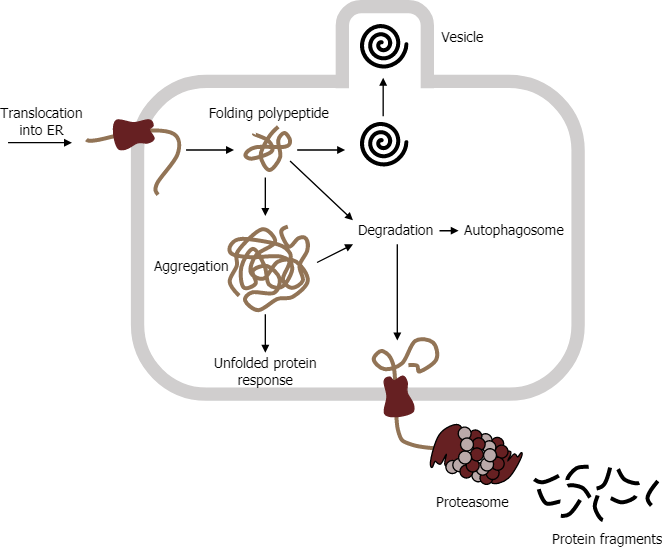

Protein Degradation and Quality Control

Improperly folded proteins can contribute to many disease processes related to misfolding events. Typically, folding is facilitated in the ER using a chaperone called binding immunoglobulin protein; however, an altered protein (due to mutation) can lead to aggregation. Binding immunoglobulin protein requires an HSP70 molecular chaperone in the RER lumen that binds newly synthesized proteins as they are cotranslated and prevents premature folding. Binding immunoglobulin protein accumulation can initiate the unfolded protein response (Figure 7).

E3 ubiquitin ligase is often responsible for tagging aggregates using a small protein called ubiquitin, which targets the protein to the proteasome. The proteasome consists of two subunits (19S and 20S) to make a functional 26S proteasome. Inside the proteasome, the polypeptide chains are cleaved back to their native amino acids for potential reuse in other translational events. However, if the aggregates accumulate, in some instances, they can contribute to any number of neurodegenerative disorders.

Learning Activity: Chaperones and Misfolded Proteins

Watch the following videos and answer the associated questions.

- “Chaperones and Misfolded Proteins” (4:20 min) by Neural Academy (2019).

- What is a molten globule?

- Why do improperly folded proteins aggregate?

- What are two mechanisms by which a cell deals with improperly folded proteins?

- “What is the Unfolded Protein Response?” (2:47 min) by UC San Francisco (UCSF) (2014).

- Describe the unfolded protein response in your own words.

- How is the unfolded protein response related to cancer, diabetes and Parkinson’s disease?

- Ubiquitin Proteasome System programme: “Technion Nobel discovery Ubiquitin the kiss of death saves your life” (3:22 min) by Technion (2016)

- Describe two ways in which a misregulation of the unfolded protein response can affect human health.

- Describe how a polyubiquitin chain is made. What is its significance?

The Golgi Apparatus

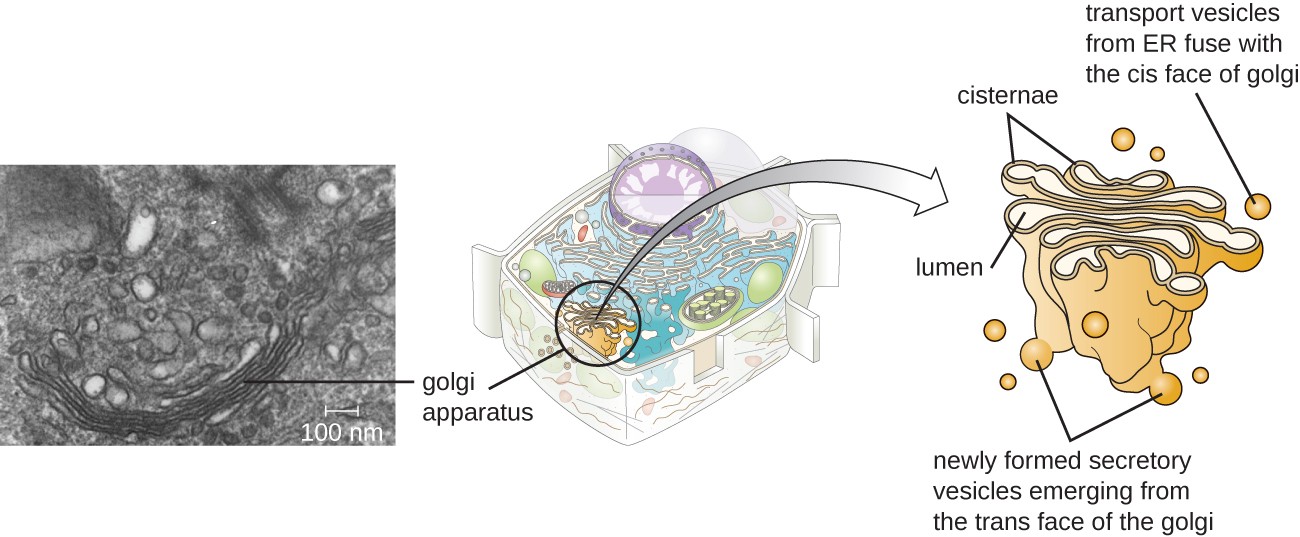

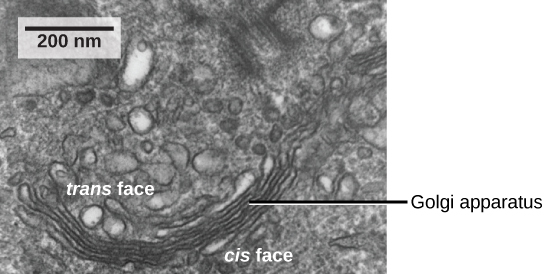

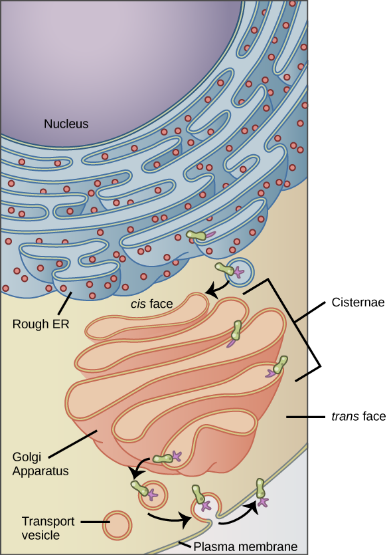

As mentioned previously, vesicles can bud from the ER, but where do the vesicles go? Before reaching their final destinations, the lipids or proteins within the transport vesicles must be sorted, packaged, and tagged so they end up in the right place. Sorting, tagging, packaging, and distributing lipids and proteins occurs in the Golgi apparatus (also called the Golgi body), a series of flattened membranous sacs stacked together. Each membranous sac has a single lipid bilayer and is called a dictyosome (Figure 8). The Golgi apparatus was discovered within the endomembrane system in 1898 by Italian scientist Camillo Golgi (1843–1926), who developed a novel staining technique that showed stacked membrane structures within the cells of Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria.

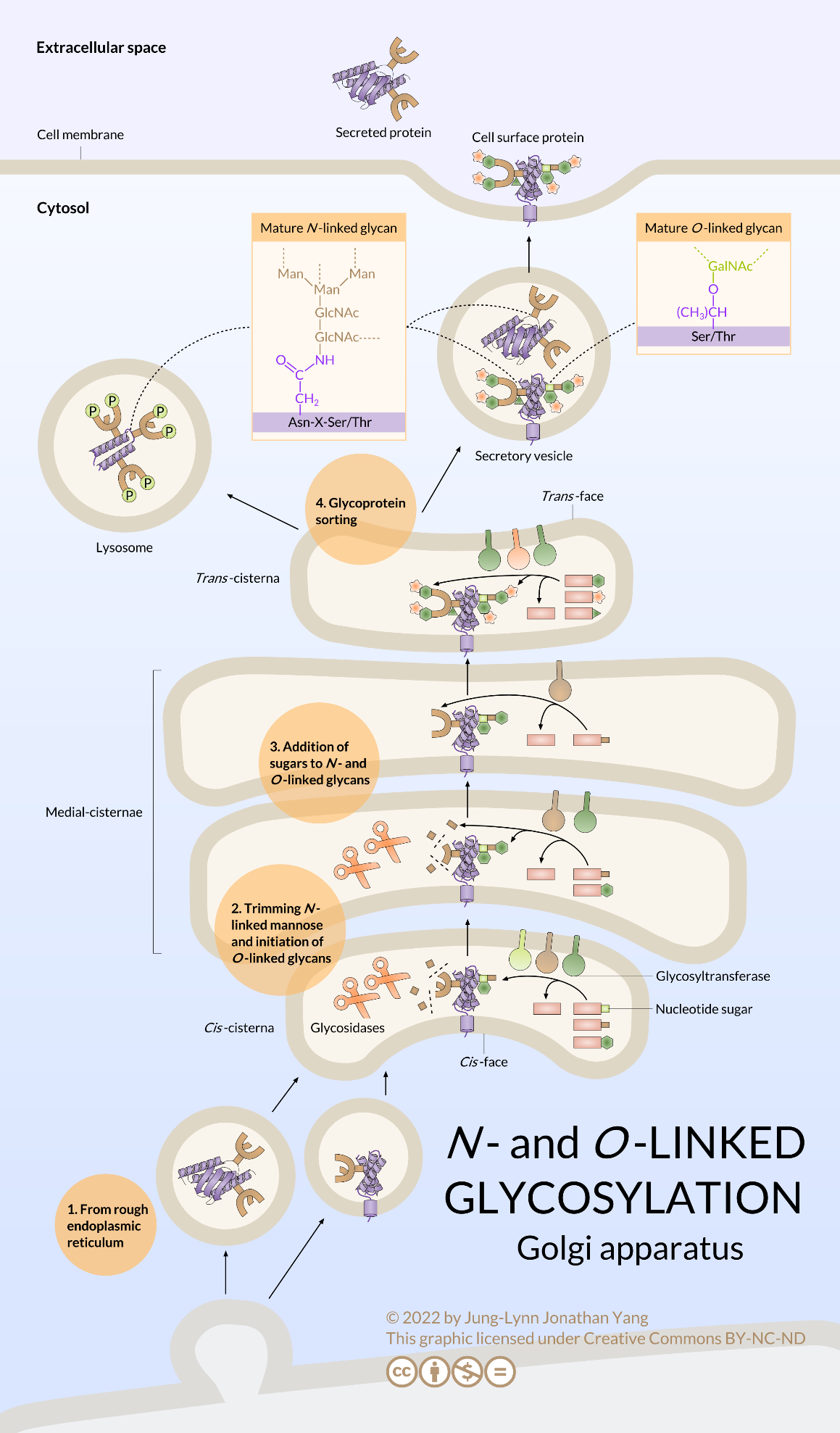

The Golgi apparatus has a receiving face, called the cis-face, near the ER and a releasing face, called the trans face, on the side facing away from the ER, toward the cell membrane (Figure 9). The transport vesicles that form from the ER travel to the receiving face to fuse with it and empty their contents into the lumen of the Golgi apparatus. As the proteins and lipids travel through the Golgi, they undergo further posttranslational modifications. The most frequent modification is adding short sugar molecule chains (glycosylation). Additionally, some proteins require Golgi-associated cleavage to produce a mature protein ready for trafficking. The Golgi packages the modified and tagged proteins into vesicles that bud from the trans face of the Golgi. Some of these vesicles, called transport vesicles, deposit their contents into other parts of the cell for use there. Other vesicles, called secretory vesicles, fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents outside the cell.

Glycosylating enzymes in the Golgi apparatus modify lipids and proteins to produce glycolipids, glycoproteins, or proteoglycans. Glycolipids and glycoproteins are often inserted into the plasma membrane and are crucial for signal recognition by other cells or infectious particles. Distinguishing different types of cells from one another can be done by looking at the structure and arrangement of the glycolipids and glycoproteins in their plasma membranes. These glycolipids and glycoproteins commonly also serve as cell surface receptors.

The amount of Golgi in different cell types again illustrates that form follows function within cells. Cells that engage in a great deal of secretory activity (such as cells of the salivary glands that secrete digestive enzymes or cells of the immune system that secrete antibodies) have relatively more Golgi. In plant cells, the Golgi has an additional role of synthesizing polysaccharides, some of which the cell wall incorporates and some of which other parts of the cell use.

Learning Activity: Vesicular Flow

It is important to become familiar with vesicular flow through the endomembrane system.

- Watch the following videos. Make your own notes.

- Animation that journeys into the human cell revealing the Golgi body “Golgi Body 3-D” (30 s) by National Human Genome Research Institute (2015).

- Overview of the endomembrane system “Endomembrane system | Structure of a cell | Biology | Khan Academy” (6:19 min) by Khan Academy (2015).

- “Endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi bodies | Biology | Khan Academy” (11:39 min) by Khan Academy (2014).

- Watch the video “Protein Trafficking” (3:20 min) by Ndsuvirtualcell (2008) and answer the following questions:

- Describe the cis-maturation model of vesicle movement through the Golgi apparatus.

- What happens to vesicles as they bud from the trans-Golgi cisternae?

- Arrange the following terms in order and draw your own picture: trans-Golgi cisterna, cis-Golgi cisterna, RER, secretory vesicle, plasma membrane, medial-Golgi cisterna.

Self-Check

- Why does the cis-face of the Golgi not face the plasma membrane?

Show/Hide answer.

Transport vesicles leaving the ER fuse with a Golgi apparatus on its receiving, or cis, face. The Golgi apparatus processes the proteins, and then additional transport vesicles containing the modified proteins and lipids pinch off from the Golgi apparatus on its outgoing, or trans, face. These outgoing vesicles move to and fuse with the plasma membrane or the membrane of other organelles.

- Is it correct to say that the nuclear membrane is part of the endomembrane system? Explain.

Show/Hide answer.

Since the external surface of the nuclear membrane is continuous with the rough endoplasmic reticulum, which is part of the endomembrane system, then it is correct to say that it is part of the system.

- Drag and drop labels to the numbers 1-11.

Roles of the ER and Golgi Apparatus in Protein Glycosylation

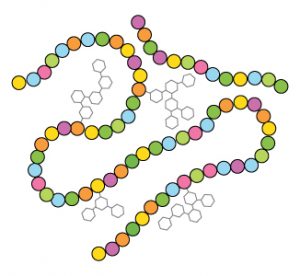

Glycosylation is the reaction in which an oligosaccharide (or glycan) attaches to another molecule’s hydroxyl or other functional group. In biology (but not always in chemistry), glycosylation usually refers to an enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Glycosylation is a form of cotranslational and posttranslational modification. Glycans serve a variety of structural and functional roles in membrane and secreted proteins. Proteins tend to clump or stick together (aggregate), and adding a sugar coating makes the polypeptide puffier or swollen (Figure 10). Aggregation influences folding and fills the spaces between molecules and entire cells, influencing cell-to-cell interactions with particular importance in cell adhesion. Glycosylated proteins are also important and clinically relevant opportunistic receptors for viruses and toxins entering the cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis. They are also common cell surface antigens (of which ABO blood types are probably the most known example). Lastly, added sugar residues often act as molecular flags or recognition signals to other cells that come in contact with them.

The following two general types of glycosylation reactions occur in cells:

- N-linked glycans attach to the nitrogen atom of the side chain amide group in asparagine residues. N-linked glycosylation requires a special lipid called dolichol phosphate to participate.

- O-linked glycans attach to the hydroxyl oxygen of serine, threonine, tyrosine, hydroxylysine or hydroxyproline side chains, or to oxygens on lipids such as ceramide.

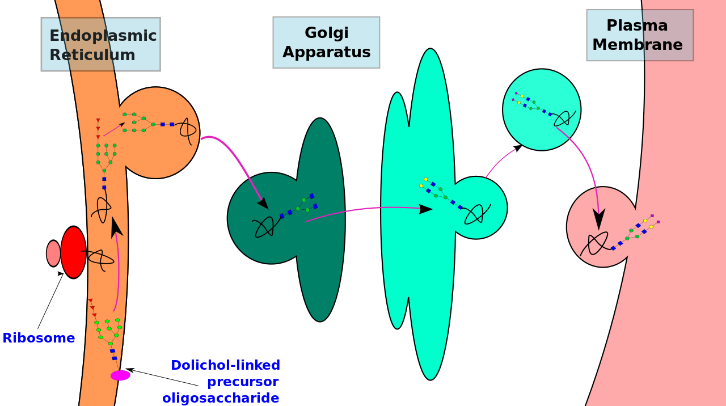

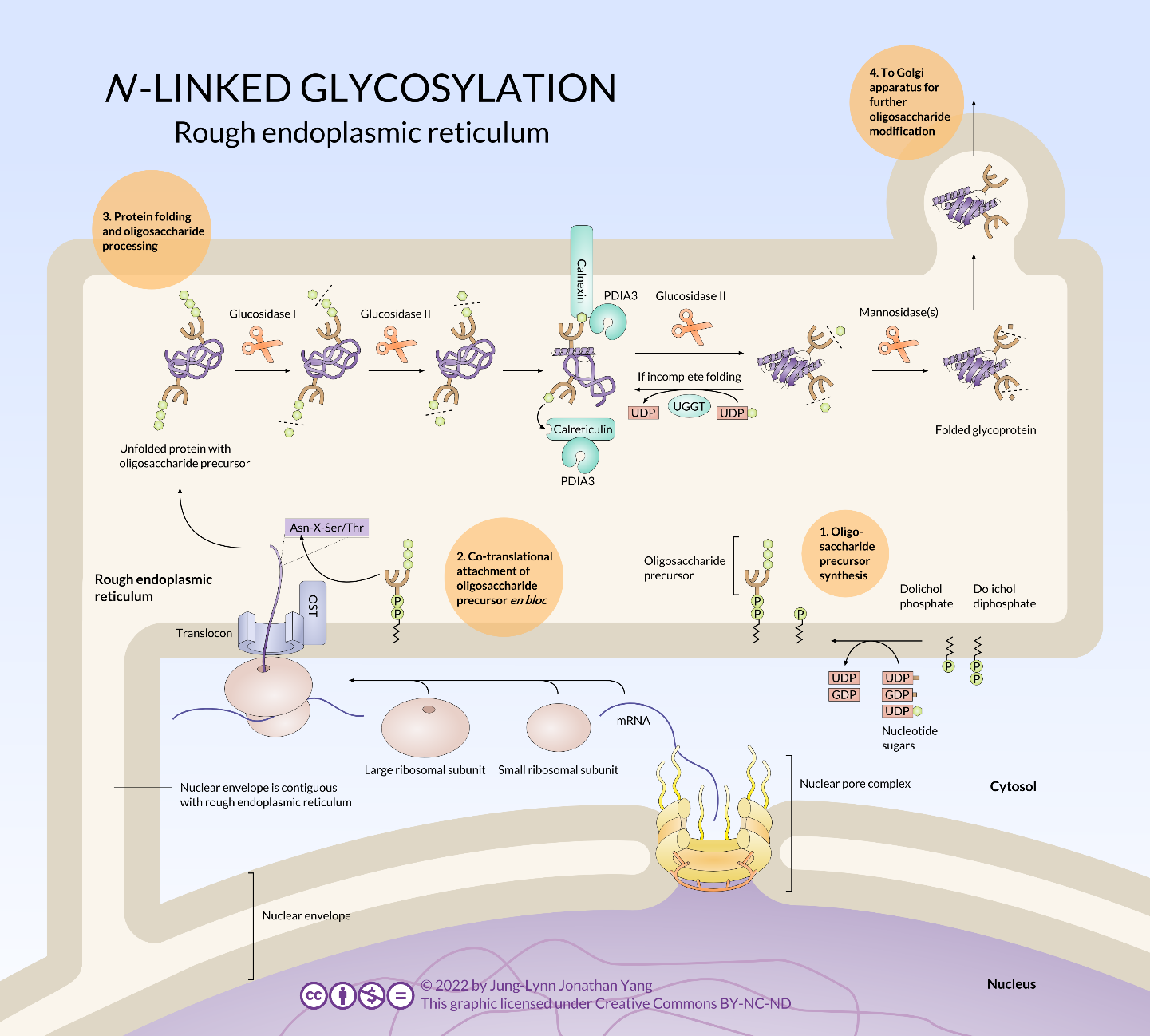

N-Linked Protein Glycosylation Begins in the RER

N-linked glycosylation begins in the RER, but O-linked glycosylation does not occur until the polypeptide moves into the Golgi apparatus (Figure 11). Therefore, it is also the case that N-linked glycosylation usually begins as a cotranslational mechanism, whereas O-linked glycosylation must occur posttranslationally. Other key differences in the two types of glycosylation are as follows:

- N-linked glycosylation occurs on asparagine (Asn) residues within an Asn-X-Ser or Asn-X-Thr sequence (X is any amino acid other than Pro or Asp). O-linked glycosylation occurs on the side chain hydroxyl oxygen of either serine or threonine residues determined not by surrounding sequence but by secondary and tertiary structure.

- N-linked glycosylation begins with a “tree” of 14 specific sugar residues that are then pruned and remodelled but remain fairly large. O-linked glycosylation is a sequential addition of individual sugars that does not usually extend beyond a few residues.

The N-linked glycosylation process occurs in eukaryotes, widely in archaea, and very rarely in bacteria. The protein and the cell in which it is expressed determine the nature of N-linked glycans attached to a glycoprotein. It also varies across species. Different species synthesize different types of N-linked glycan.

N-linked glycan biosynthesis occurs via the following three main steps:

- Synthesizing a dolichol-linked precursor oligosaccharide

- En bloc transfer of the precursor oligosaccharide to a protein

- Processing the oligosaccharide

Precursor oligosaccharides undergo synthesis, en bloc transfer and initial trimming in the RER. The Golgi apparatus carries out the subsequent processing and modification of the oligosaccharide chain. Thus, glycoprotein synthesis is spatially separated in different cellular compartments. Furthermore, the type of N-glycan added to a protein depends on the different enzymes present in these cellular compartments. This is yet another example of cellular compartmentalization.

However, despite the diversity, all N-glycans are synthesized through a common pathway with a common core glycan structure. The core glycan structure consists of two N-acetylglucosamine and three mannose residues. Further elaboration and modification of this core glycan results in a diverse range of N-glycan structures.

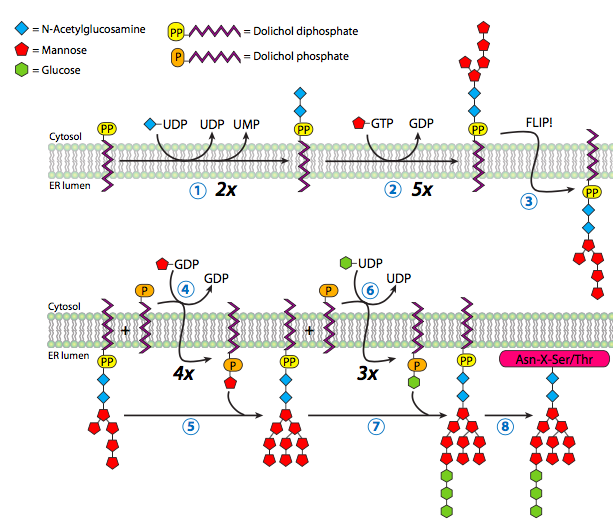

Technically, N-glycosylation begins before any protein translation occurs, as the dolichol pyrophosphate oligosaccharide (i.e., the sugar “tree” – not an official term, by the way) is synthesized in the RER (Figure 12) without being triggered by translation or protein entry.

Dolichol is a long-chain hydrocarbon (14 to 24 isoprene units of 4+1 carbons) found primarily in the RER membrane. It serves as a temporary anchor for the N-glycosylation oligosaccharide during synthesis or while waiting for an appropriate protein to glycosylate. The oligosaccharide synthesis begins with adding two N-acetylglucosamine residues to the pyrophosphate linker, followed by a mannose. From this mannose, the oligosaccharide branches, with one branch receiving three more mannose residues and the other receiving one. So far, these additions to the oligosaccharide have been taking place in the cytoplasm. Now, the glycolipid is flipped inwards to the ER lumen. Once in the lumen, it obtains four more mannoses, and three glucose residues top off the structure.

The enzymes completing glycosylation are glycosyltransferases specific to both the added sugar residue and the target oligosaccharide. The sugars used by the enzymes are not simply the sugar but nucleotide sugars — usually a sugar linked to a nucleoside diphosphate(e.g., uracil diphosphate glucose (UDP-glucose) or GDP-mannose).

Nucleotide Sugars

This process does not use all nucleotides; sugars have only been found linked to UDP, GDP, and CMP. UDP is the most versatile, binding N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), N-acetylmuramic acid, galactose, glucose, glucuronic acid, and xylose. GDP is used for mannose and fucose, while CMP is for N-acetylneuraminic and sialic acid.

Download a fun infographic that shows the chemical structures of the nucleotide sugars. This infographic is a parody of a candy guide. The snacks shown are for decorative purposes and are not necessarily related to the molecules.

The N-linked oligosaccharide has two physiological roles:

- Acting as the base for further glycosylation

- Being used as a marker for error-checking of protein folding by the calnexin-calreticulin system (Figure 13)

Once the oligosaccharide attaches to the new polypeptide, further glycosylation begins when glucosidase I and glucosidase II remove two of the glucose. The last glucose is necessary to help the glycoprotein dock with either calnexin or calreticulin (Figure 13, Step 3). The chaperones calnexin and calreticulin have similar functions that help proteins fold and are associated with protein disulfide isomerase A3. Both chaperones temporarily hold onto the glycoprotein to give it time to (re)fold and possibly rearrange disulfide bonds. While calnexin is an integral protein embedded in the RER membrane, calreticulin is soluble in the RER lumen. Glucosidase II removes the glucose from the glycoprotein to dissociate the glycoprotein from calnexin/calreticulin. If the glycoprotein has not fully folded, the enzyme UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase recognises it, adding back the glucose residue and forcing the gycoprotein to go through the calnexin/calreticulin cycle again in hopes of folding correctly. If it has folded correctly, a mannosidase can recognise it, which removes a mannose, completing the glycosylation modifications in the RER.

Most glycoproteins continue oligosaccharide remodelling once they have been moved from the RER to the Golgi apparatus by vesicular transport (Figure 14). There, various glycosidases and glycosyltransferases prune and add to the oligosaccharide. Although the glycosylation is consistent and stereotyped for a given protein, it is still unclear exactly how the glycosylation patterns are determined. In summary, N-glycan processing happens in RER and the Golgi body. Precursor molecules undergo initial trimming in the RER and subsequent processing in the Golgi. N-linked glycoproteins in the Golgi may take on additional sugar residues in the form of O-linked glycans.

Exploiting Biological Processes to Aid in Human Health

Two common antibiotics, tunicamycin and bacitracin, can target N-linked glycosylation, although their antibiotic properties come from disrupting the formation of bacterial cell walls.

Tunicamycin is an analogue of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. It can disrupt the initial oligosaccharide formation inside eukaryotic cells by blocking the initial N-acetylglucosamine addition to the dolichol-phosphate. Since it can be transported into eukaryotic cells, tunicamycin is not clinically useful due to its toxicity.

On the other hand, bacitracin is a small cyclic polypeptide that binds to dolichol-PP to prevent its dephosphorylation to dolichol-P, which is needed to build the oligosaccharide. Bacitracin is not cell-permeable, so even though it and tunicamycin affect bacteria similarly by disrupting extracellular glycolipid synthesis required for cell wall formation, it is harmless to eukaryotes and thus applicable as a therapeutic antibiotic.

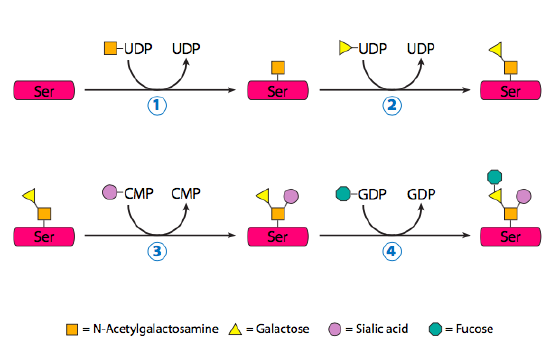

O-Linked Protein Glycosylation Takes Place Entirely in the Golgi

O-linked glycoproteins begin their glycosylation when the Golgi-specific enzyme, N-acetylgalactosamine transferase, attaches an N-acetylgalactosamine to the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine (Figure 15). Determining which residue to glycosylate appears to be directed by secondary and tertiary structures, and the process often occurs in dense clusters of glycosylation. Despite being relatively small additions (usually less than five residues), the combined oligosaccharide chains attached to an O-linked glycoprotein can contribute over 50% of the glycoprotein’s mass. Two well-known O-linked glycoproteins are mucin, a component of saliva, and ZP3, a component of the zona pellucida (which protects egg cells). These two examples also illustrate a crucial property of glycoproteins and glycolipids in general: sugars are highly hydrophilic and hold water molecules to them, greatly expanding the volume of the protein.

Learning Activity: Glycosylation and Glycoproteins

- Watch the video “Glycosylation and Glycoproteins” (12:39 min) by Andrey K (2015).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the name of the short sugar molecules covalently attached to amino acids?

- To which amino acids can these sugar molecules be attached?

- What are the names of the two types of bonds that can form between the amino acid and sugar molecules? Which amino acids and atoms are involved in each type of bond?

- There may be many asparagine amino acid residues in a polypeptide. How does the cell ‘know’ which asparagine to glycosylate? Which figure in this text shows the answer to this question?

- In which organelle(s) do the two types of glycosylation events begin and end?

Glycosyltransferases and ABO blood groups

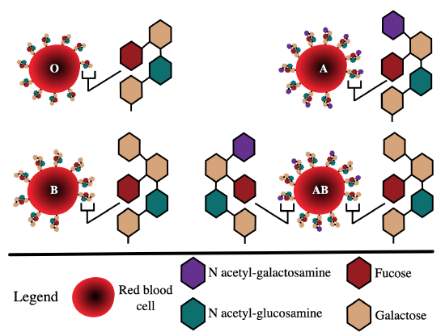

As mentioned above, glycosylated proteins and lipids are common cell surface antigens; these contribute to human ABO blood types (Figure 16).

Learning Activity: Glycosylation and ABO Blood Types

Glycosylation plays a crucial role in determining human ABO blood types. Knowing what ABO blood type a person has is necessary for blood donation and transfusion medicine.

- Watch the following videos:

- “Glycosyltransferases and ABO Blood Groups” (8:56 min) by Andrey K (2015).

- “Oligosaccharides and Human Blood Groups” (2:30 min) by Walter Jahn (2014).

- “Biochemistry of ABO Antigens” (4:30 min) by Hussain Biology (2018).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the difference between the A and B blood group antigens?

- Why does an individual have a particular blood type?

Learning Activity: Glycoprotein Topology

Consult Figure 17 below and answer the following question:

- If a glycan is added to peripheral membrane protein in the lumen (inside) of the RER and in the Golgi cisternae, would it end up on the inside or outside of the plasma membrane? Draw this on your picture from the Learning Activity: Vesicular Flow.

Key Concepts and Summary

As discussed in Unit 3, Topic 1, newly synthesized proteins enter the biosynthetic-secretory pathway in the ER by crossing the ER membrane from the cytosol. During their subsequent transport — from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and from the Golgi apparatus to the cell surface and elsewhere — these proteins pass through a series of compartments, where they are successively modified. Transfer from one compartment to the next involves a delicate balance between forward and backward (retrieval) transport pathways. The pathway from the ER to the cell surface involves many sorting steps, which continually select membrane and soluble luminal proteins for packaging and transport — in vesicles or organelle fragments that bud from the ER and Golgi apparatus.

The endomembrane system includes the nuclear envelope, lysosomes, vesicles, the ER, the Golgi apparatus, and the plasma membrane. These cellular components work together to modify, package, tag, and transport proteins and lipids that form the membranes.

The RER modifies proteins and synthesizes phospholipids in cell membranes. The SER synthesizes carbohydrates, lipids, and steroid hormones, detoxifies medications and poisons, and stores calcium ions. Sorting, tagging, packaging, and distributing lipids and proteins take place in the Golgi apparatus. Budding RER and Golgi membranes create lysosomes. Lysosomes digest macromolecules, recycle worn-out organelles, and destroy pathogens.

Glycosylation is the process by which a carbohydrate covalently attaches to a target molecule, typically a protein and lipid. A glycosylated protein is called a glycoprotein, and a glycosylated lipid is called a glycolipid. This modification serves various functions. For instance, some proteins do not correctly fold unless they are glycosylated. In other cases, proteins are unstable unless they contain oligosaccharides linked at the amide nitrogen of specific asparagine residues.

N-linked glycosylation is a prevalent form of glycosylation important for folding many eukaryotic glycoproteins along with cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix attachment. It begins in the RER. O-linked glycosylation is a form of glycosylation that occurs in eukaryotes in the Golgi apparatus but also in archaea and rarely in bacteria.1

Key Terms

endomembrane system

group of organelles and membranes in eukaryotic cells that work together modifying, packaging, and transporting lipids and proteins

endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

series of interconnected membranous structures within eukaryotic cells that collectively modify proteins and synthesize lipids

Golgi apparatus

eukaryotic organelle comprised of a series of stacked membranes that sorts, tags, and packages lipids and proteins for distribution

lysosome

organelle in an animal cell that functions as the cell’s digestive component; it breaks down proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles

nuclear envelope

double-membrane structure that constitutes the nucleus’ outermost portion

rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER)

region of the endoplasmic reticulum that is studded with ribosomes and engages in protein modification and phospholipid synthesis

smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER)

region of the endoplasmic reticulum that has few or no ribosomes on its cytoplasmic surface and synthesizes carbohydrates, lipids, and steroid hormones; detoxifies certain chemicals (like pesticides, preservatives, medications, and environmental pollutants), and stores calcium ions

vesicle

small, membrane-bound sac that functions in cellular storage and transport; its membrane is capable of fusing with the plasma membrane and the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus

Long Descriptions

Figure 16 Image Description: Type O has one fucose, two galactose, and one N acetyl-glucosamine. Type A has one fucose, two galactose, one N acetyl-glucosamine, and one N acetyl-galactosamine. Type B has one fucose, three galactose, and one N acetyl-glucosamine. Type AB has two different antigen compositions. The first is one fucose, two galactose, one N acetyl-glucosamine, and one N acetyl-galactosamine. The second is one fucose, three galactose, and one N acetyl-glucosamine. [Return to Figure 16]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 3.43 from OpenStax Microbiology (Parker et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 3.44 [left side] from OpenStax Microbiology (Parker et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI)… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 11.3.9 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 11.3.10 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 11.3.11 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 17.3 from Cell Biology, Genetics, and Biochemistry for Pre-Clinical Students (LeClair 2021) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 3.45 from OpenStax Microbiology (Parker et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 5.10.1 [modification of work by Louisa Howard; scale-bar data from Matt Russell] from LibreTexts BIOLOGY 211: Cell Biology (BIOLOGY 211 … 2021) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 10:https://uta.pressbooks.pub/cellphysiology/chapter/posttranslational-modifications-of-proteins/

- Figure 11: Biosynthesis of N-glycan by Dna 62 (2014), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 11.4.12 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 13: N-glycosylation is… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 14: N-linked glycosylation… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: Figure 11.4.14 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 16: ABO blood group diagram by InvictaHOG (2006), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17: Figure 4.4.1 from OpenStax General Biology 1e (OpenStax 2022) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

Andrey K. Glycosylation and glycoproteins [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Apr 22, 12:39 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHpQuV80xhs.

Andrey K. Glycosyltransferases and ABO blood groups [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Apr 23, 8:56 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSVbO2sHlBE.

BIOLOGY 211: cell biology. 2021. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Principles_of_Biology/01%3A_Chapter_1.

BIOLOGY 211: cell biology. 2021. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. Chapter 5.10: the Golgi apparatus. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Principles_of_Biology/01%3A_Chapter_1/05%3A_Cell_Structure_and_Function/5.10%3A_The_Golgi_Apparatus.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Chapter 4.4: the endomembrane system and proteins. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/4-4-the-endomembrane-system-and-proteins.

Dna 621. 2014. Biosynthesis of n-glycan [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2014 Mar 27; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Biosynthesis_of_N-glycan.svg.

Hussain Biology. Biochemistry of ABO antigens [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Jan 27, 4:30 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kf4eb-CBF-s.

InvictaHOG. 2006. ABO blood group diagram [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2023 Feb 15; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ABO_blood_group_diagram.svg.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. The endomembrane system. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jul 23]. AP®︎/college biology, Lesson 8: cell compartmentalization and its origins. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/cell-structure-and-function/cell-compartmentalization-and-its-origins/a/the-endomembrane-system.

Khan Academy. Endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi bodies | biology | Khan Academy [Video] . YouTube. 2014 Jan 7, 11:39 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6UqtgH_Zy1Y.

Khan Academy. Endomembrane system | structure of a cell | biology | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Jul 23, 6:19 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vC-cEWJxDRY.

Learnbiologically. Endoplasmic reticulum [Video]. YouTube. 2013 Jan 3, 2:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eH5k8XYKycs.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students.

LeClair RJ. 2021. Cell biology, genetics, and biochemistry for pre-clinical students. Roanoke (VA): Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 17.1: cellular organelles and the endomembrane system. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Basic_Science/Cell_Biology_Genetics_and_Biochemistry_for_Pre-Clinical_Students/17%3A_Cytoplasmic_Membranes/17.01%3A_Cellular_organelles_and_the_endomembrane_system.

Medic Tutorials – Medicine and Language. Intracellular organelles- rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Feb 18, 7:30 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJyFqNtnaEE.

National Human Genome Research Institute. Golgi body 3-D [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Mar 19, 0:30 minutes. [accessed 2025 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ady9okEbweg.

Ndsuvirtualcell. Protein trafficking [Video]. YouTube. 2008 Mar 3, 3:27 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rvfvRgk0MfA.

Neural Academy. Cahperones and misfolded proteins [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Aug 11, 4:10 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ESC3CSApNnk.

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax).

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. Chapter 4.4: the endomembrane system and proteins, Figure 4.4.1. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax)/2%3A_The_Cell/04%3A_Cell_Structure/4.4%3A_The_Endomembrane_System_and_Proteins#:~:text=1%3A%20If%20a%20peripheral%20membrane,outside%20of%20the%20plasma%20membrane%3F&text=It%20would%20end%20up%20on,membrane%2C%20it%20turns%20inside%20out.

Parker N. Schneegurt M, Thi Tu A-H, Lister P, Foster BM. 2016. Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction.

Parker N. Schneegurt M, Thi Tu A-H, Lister P, Foster BM. 2016. Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 3.4: unique characteristics of eukaryotic cells. Figures 3.43 to 3.45. https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/3-4-unique-characteristics-of-eukaryotic-cells.

Rachel Davidowitz. Active cage mechanisms of chaperonin-assisted protein folding demonstrated at single-molecule level [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Oct 6, 1:37 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–NcNeLc1mo.

Technion. Technion Nobel discovery Ubiquitin the kiss of death saves your life [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Aug 30, 3:22 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9EGAAys7ZU.

UC San Francisco (UCSF). What is the unfolded protein response? [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Sep 11, 2:47 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vy4m-fUOn9o.

Walter Jahn. Oligosaccharies and human blood groups [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Sep 14, 2:30 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtGFp7gK9no.

1 Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Glycosylation. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Aug 27; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Glycosylation&oldid=1172448520.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. N-linked glycosylation. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Sep 27; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=N-linked_glycosylation&oldid=1177362927.

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 11.3: protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum, Chapter 11.4: n-linked protein glycosylation begins in the ER. Figures 11.3.9 to 11.3. 11, 11.4.12, 11.4.14. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong)/11%3A_Protein_Modification_and_Trafficking/11.04%3A_N-linked_Protein_Glycosylation_Begins_in_the_ER.

Yang J-L J. 2022. Figure 3, 13, 14 created for this course

https://uta.pressbooks.pub/cellphysiology/chapter/posttranslational-modifications-of-proteins/

group of organelles and membranes in eukaryotic cells that work together modifying, packaging, and transporting lipids and proteins

double-membrane structure that constitutes the nucleus’ outermost portion

series of interconnected membranous structures within eukaryotic cells that collectively modify proteins and synthesize lipids

eukaryotic organelle comprised of a series of stacked membranes that sorts, tags, and packages lipids and proteins for distribution

organelle in an animal cell that functions as the cell’s digestive component; it breaks down proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles

small, membrane-bound sac that functions in cellular storage and transport; its membrane is capable of fusing with the plasma membrane and the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus

region of the endoplasmic reticulum that is studded with ribosomes and engages in protein modification and phospholipid synthesis

region of the endoplasmic reticulum that has few or no ribosomes on its cytoplasmic surface and synthesizes carbohydrates, lipids, and steroid hormones; detoxifies certain chemicals (like pesticides, preservatives, medications, and environmental pollutants), and stores calcium ions