1.2 Cellular Size

Introduction

The image in Figure 1 shows a bacterial cell (coloured green) attacking human red blood cells (large red cells). The bacterium causes a disease called relapsing fever. The bacterial and human cells look very different in size and shape. Although all living cells have certain things in common (e.g., a plasma membrane and cytoplasm), different types of cells, even within the same organism, may have their own unique structures and functions. Cells with different functions generally have different shapes suitable for their specific job. This returns to the principle of form following function.

Cells vary not only in shape but also in size, as this example shows. In most organisms, however, even the largest cells are no bigger than the period at the end of this sentence. Why are cells so small?

The volume of a typical eukaryotic cell is 10 to 100 times larger than a typical bacterial cell. Eukaryotic life would not be possible without a division of labour of eukaryotic cells among different organelles (membrane-bound structures). Imagine a bacterium as a 100-square-foot room (the size of a small bedroom or a large walk-in closet!) with one door. Now imagine a room 100 times as big. That is, imagine a 10,000 square foot ‘room.’ You would expect many smaller rooms inside such a large space, each with its own door(s). The eukaryotic cell is a lot like that large space, with lots of interior “rooms” (i.e., organelles) with their own entryways and exits. The smaller prokaryotic “room” has a much larger plasma membrane surface area/volume ratio than a typical eukaryotic cell, enabling required environmental chemicals to enter and quickly diffuse throughout the cytoplasm of the bacterial cell. Therefore, chemical communication between parts of a small cell is rapid. In contrast, communication over a larger expanse of cytoplasm inside a eukaryotic cell requires the coordinated activities of subcellular compartments. Such communication might be relatively slow. In fact, eukaryotic cells have lower rates of metabolism, growth, and reproduction than prokaryotic cells. The existence of large cells required the evolution of a division of labour supported by compartmentalization.

Unit 1, Topic 2 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 1, Topic 2, you will be able to:

- Diagram and compare the surface-area-to-volume ratio of a small and large cube.

- Calculate the surface-area-to-volume ratio of various cube sizes.

- Explain three limitations to cell size.

- Explain the strategies used by cells to overcome limitations to cell size.

- Understand the relationship between cell structure and function.

- Discuss why cellular compartments arose during evolution.

| Unit 1, Topic 2—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 1, Topic 2 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Size and Scale of Cells. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Limitations of Diffusion. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Overcoming Limitations of Cell Size. | 5 |

Three Main Factors That Limit Cell Size

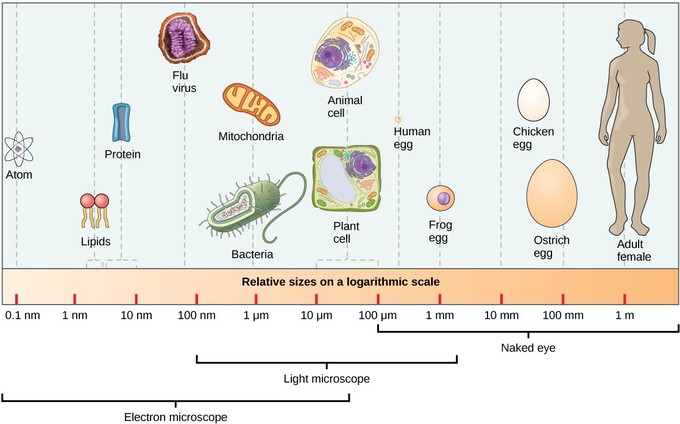

At 0.1 to 5.0 micrometres (μm) in diameter, prokaryotic cells are significantly smaller than eukaryotic cells, having diameters ranging from 10 to 100 μm (Figure 2). An object must measure about 100 µm to be visible without a microscope. The small size of prokaryotes allows ions and organic molecules that enter them to quickly diffuse to other parts of the cell. Similarly, any waste produced within a prokaryotic cell can quickly diffuse out. This is not the case in eukaryotic cells, which have developed different structural adaptations to enhance intracellular transport.

In general, small size is necessary for all cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Most organisms, even very large ones, have microscopic cells. Why do cells not get bigger instead of remaining tiny and multiplying? What limits cell size? The answers to these questions are clear when considering how a cell functions. A cell must quickly pass substances into and out of the cell to carry out life processes. For example, it must pass nutrients and oxygen into the cell and waste products out of the cell. Anything that enters or leaves a cell must cross its outer surface. This need to pass substances across the surface is one way that limits how large a cell can be.

Self-Check

How does a typical prokaryotic cell compare in size to a eukaryotic cell?

- It is similar in size

- It is larger by a factor of 10

- It is smaller by a factor of 100

- It is smaller by a factor of one million

Show/Hide answer.

c. It is smaller in size by a factor of 100

Learning Activity: Size and Scale of Cells

Try to grasp the sizes and scales of different types of cells using this dynamic web app—compare sizes from coffee beans to carbon atoms.

- Watch the video “Relative Sizes of Bacteria and Viruses | HHMI BioInteractive Video” (1:44 min) by BioInteractive (2018), where Dr. Finlay and Dr. Richard Ganem use physical analogies to compare the size of bacteria and viruses relative to a standard mammalian cell.

- Go to the Learn.Genetics website by GSLC (2020) and complete the activity. Move the toggle to the right to view the relative sizes of various items.

- Answer the following questions:

- Did the relative sizes of any of the objects surprise you?

- Does the similar size and shape of the mitochondrion and the E. coli bacterial cell surprise you?

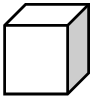

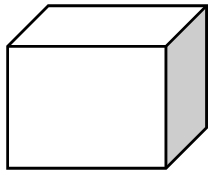

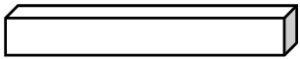

Factor 1: Surface-Area-to-Volume Ratio

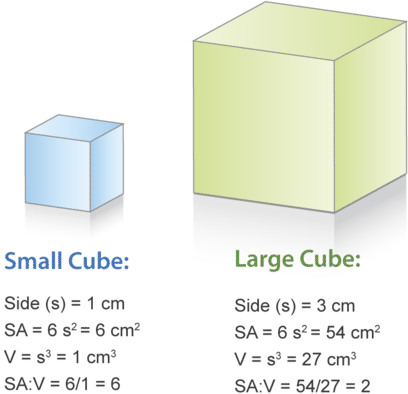

Look at the two cubes in Figure 3. A larger cube has less surface area relative to its volume than a smaller cube. This relationship also applies to cells; a larger cell has less surface area relative to its volume than a smaller cell. A cell with a larger volume also needs more nutrients and oxygen and produces more waste. Because all these substances must pass through the surface of the cell, a cell with a large volume will not have enough surface area to allow it to meet its needs. The larger the cell is, the smaller its ratio of surface-area-to-volume, and the harder it will be for the cell to get rid of its waste and take in necessary substances to maintain homeostasis. A cell with insufficient surface area to support its increasing volume either divides or dies. This is one factor that limits the size of a cell.

There are a few monster bacteria that fall outside the norm in size and still manage to grow and reproduce very quickly. One such example is Thiomargarita namibiensis, which can measure from 100–750 μm in length, compared to the more typical 4 μm length of E. coli. Thiomargarita namibiensis maintains its rapid reproductive rate by producing large vacuoles or bubbles that occupy a large portion of the cell. These vacuoles reduce the volume of the cell, increasing the surface-to-volume ratio. Other large bacteria utilize a ruffled membrane for their outer surface layer. This membrane type increases the surface area and the surface-to-volume ratio, allowing the cell to maintain its rapid reproductive rate.

Surface Area

Small Intestine

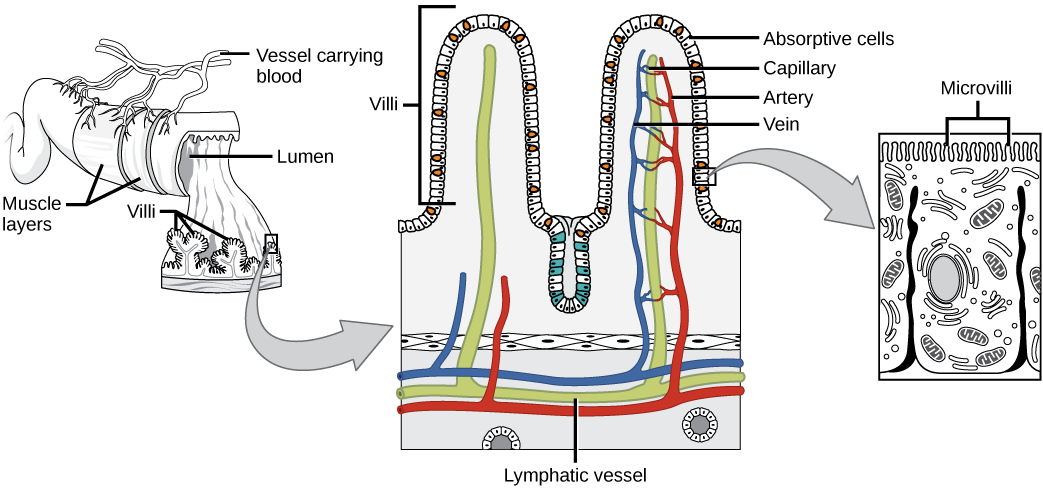

Chyme moves from the stomach to the small intestine. The small intestine is the organ that digests protein, fats, and carbohydrates. The small intestine is a long tube-like organ with a highly folded surface containing finger-like projections called the villi (singular is villus). The apical surface of each villus has many microscopic projections called microvilli. These structures, illustrated in Figure 4, are lined with epithelial cells on the luminal side; they allow the nutrients to be absorbed from the digested food and absorbed into the bloodstream on the other side. The villi and microvilli (with their many folds) increase the intestine’s surface area and the absorption efficiency of the nutrients. Absorbed nutrients in the blood are carried into the hepatic portal vein, which leads to the liver. There, the liver regulates the distribution of nutrients to the rest of the body and removes toxic substances, including drugs, alcohol, and some pathogens.

Mammalian Lungs

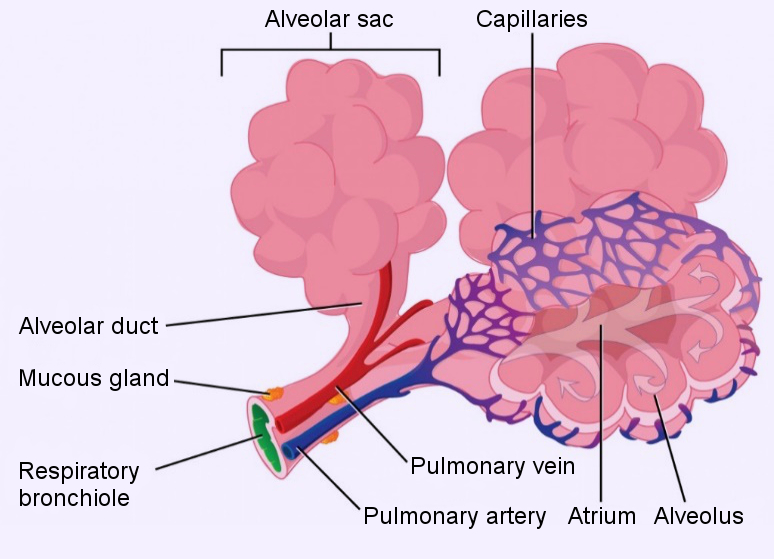

The terminal bronchioles subdivide into microscopic branches called respiratory bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles subdivide into several alveolar ducts. Numerous alveoli and alveolar sacs surround the alveolar ducts. The alveolar sacs resemble bunches of grapes tethered to the end of the bronchioles (Figure 5). The alveolar ducts in the acinar region are attached to the end of each bronchiole. At the end of each duct are approximately 100 alveolar sacs, each containing 20 to 30 alveoli that are 200 to 300 microns in diameter. Gas exchange occurs only in alveoli.

Alveoli consist of thin-walled parenchymal cells, typically one-cell thick, that look like tiny bubbles within the sacs. Alveoli are in direct contact with capillaries (one cell thick) in the circulatory system. Such intimate contact ensures that oxygen diffuses from alveoli into the blood, distributing it to the rest of the body. In addition, the carbon dioxide produced by cells as a waste product diffuses from the blood into the alveoli to be exhaled by the lungs. The anatomical arrangement of capillaries and alveoli emphasizes the structural and functional relationship of the respiratory and circulatory systems. Because each alveolar sac has numerous alveoli (~300 million per lung) and each alveolar duct has numerous sacs at the ends, the lungs have a sponge-like consistency. This organization results in a very large surface area available for gas exchange. The surface area of the alveoli in the lungs is approximately 75 m2. This large surface area, combined with the thin-walled nature of the alveolar parenchymal cells, allows gases to easily diffuse across the cells.

Self-Check

Which of the following statements about the small intestine is false?

- Absorptive cells that line the small intestine have microvilli, small projections that increase surface area and aid in the absorption of food.

- The inside of the small intestine has many folds called villi.

- Microvilli are lined with blood vessels as well as lymphatic vessels.

- The inside of the small intestine is called the lumen.

Show/Hide answer.

c. Microvilli are lined with blood vessels as well as lymphatic vessels.

Factor 2: Rates of Intracellular Diffusion

The second factor limiting cell size is the rate of intracellular diffusion. As discussed above, cells must move substances across membranes to maintain homeostasis, and cells can only increase in size if their membrane surface area is sufficient for this movement. However, cell size is also limited by how quickly the cell can move molecules around within the cytosol to reach the location(s) where their function(s) are required. The internal volume of the cell (excluding the nucleus) is called the cytoplasm, which contains organelles, cytoskeletal fibres, and semifluid cytosol. Many molecules move through the cytosol, which has the consistency of honey, by diffusion.

Diffusion is the unaided movement of molecules from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration. Since molecules are in constant motion, they will bounce off each other and flow toward the area of fewer molecules. The ability of a molecule to move through the cytosol by diffusion is affected by its size. For example, the

Diffusion is the unaided movement of molecules from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration. Since molecules are in constant motion, they will bounce off each other and flow toward the area of fewer molecules. The ability of a molecule to move through the cytosol by diffusion is affected by its size. For example, large molecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, have a limiting diffusion rate. Once again, cells have a backup plan. Many eukaryotic cells move substances around using specialized carrier proteins, while others use cytoplasmic streaming or cyclosis (in plants). Some cells move molecules within vesicles with the aid of motor proteins that are transported along cytoskeletal fibres in the cytoplasm, as shown in Figure 6. This topic will be covered in detail later in this course.

In summary, cells have developed various strategies to avoid limitations imposed by the low diffusion rates of large macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids will be limited. Once again, cells have a backup plan. Many eukaryotic cells move substances around using specialized carrier proteins, while others use cytoplasmic streaming or cyclosis (in plants). Some cells move molecules within vesicles with the aid of motor proteins that are transported along cytoskeletal fibres in the cytoplasm, as shown in Figure 6. This topic will be covered in detail later in this course.

In summary, cells have developed various strategies to avoid limitations imposed by low diffusion rates.

Factor 3: Maintaining Adequate Local Concentrations of Substances

If the size of a cell increases, it would need to increase the concentration of reactants and enzymes that participate in the chemical reactions required to sustain cellular function. To maintain the appropriate level of reactants and enzymes, the number of all such molecules must increase eightfold every time the three dimensions of the cell double. For example, a chemical reaction can only occur if the substrates collide with and bind to a particular enzyme. The chances of random collisions can be increased by localizing the reactants and enzymes to a specific region rather than spreading them throughout the cytosol. This solution is known as compartmentalization; eukaryotic cells facilitate this using organelles and intracellular systems. For example, a plant leaf has the molecules necessary for photosynthesis concentrated in membrane-bound organelles called chloroplasts. Activities within a cell can be ‘stuck’ in one spot this way. Anchor them in the plasma membrane or cage them within an organelle or within organelle membranes. A second advantage of compartmentalization is to separate incompatible chemical reactions. For example, it prevents lysosomal degradation enzymes from interacting with molecules required for cellular respiration.

Learning Activity: Limitations of Diffusion

This activity will help you understand how the limitations of diffusion apply to cells of different sizes and shapes. The diffusion rate across the plasma membrane of the cell is proportional to the surface area of the plasma membrane; meanwhile, the rate of using substances is proportional to cell volume. Therefore, diffusion can only supply adequate amounts of O2, nutrients, and other substances if the surface-area-to-volume ratio is large enough.

- Complete the following table. You may download the template for the table to fill in by hand or electronically.

Hypothetical cells Surface area Volume Surface-area-to-volume ratio Distance from centre of cell to nearest cell surface

Each side 10 µm

Each side 100 µm

10 µm × 10,000 µm × 10 µm - Answer the following questions. These questions will test your ability to relate the calculations you did above to important aspects of cell size in the human body.

- What are the disadvantages of the larger cube-shaped cell compared to the smaller cell?

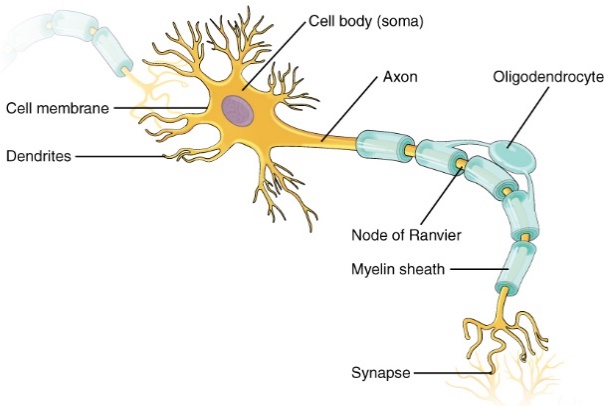

- Some cells have very long, slender extensions. For example, your body has nerve cells extending from the bottom of your spine all the way down your leg to your foot. Based on your calculations, explain how diffusion can supply enough O2 to this very long, slender extension of the nerve cell (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Parts of a neuron. (Barker 2017/Human Anatomy and Physiology II, 1st ed./Douglas College/BCcampus) CC BY 4.0 [Long Description] - Explain how the small intestine is designed to maximize the surface-area-to-volume ratio to aid in absorption.

- Explain how human lungs are designed to maximize the surface-area-to-volume ratio to aid in gas exchange.

Learning Activity: Overcoming Limitations of Cell Size

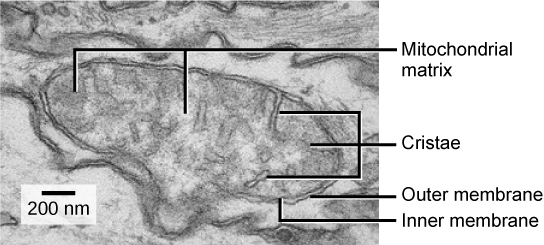

Figure 8 shows an electron micrograph of a mitochondrion produced using an electron microscope. This organelle has an outer membrane and an inner membrane. The inner membrane contains folds called cristae. The cristae membrane is where the electron transport chain and enzymes of oxidative phosphorylation, such as ATP synthase and succinate dehydrogenase, are located. ATP synthesis takes place on the inner membrane. The space between the two membranes is called the intermembrane space, and the space inside the inner membrane is the mitochondrial matrix.

- Write a few sentences commenting on why this organelle (as highlighted in the image below) has cristae. This activity should help you to integrate the strategies used by cells to overcome limitations to cell size.

Key Concepts and Summary

- A cell must quickly pass substances into and out of the cell to carry out life processes.

- For example, it must be able to pass nutrients and oxygen into the cell and waste products out of the cell.

- Anything that enters or leaves a cell must cross its outer surface. This need to pass substances across the surface is one way that limits how large a cell can be.

- As a cell grows, its volume increases much more rapidly than its surface area. Since the cell’s surface allows oxygen to enter, large cells cannot obtain enough oxygen to support themselves.

- As animals increase in size, they require specialized organs that effectively increase the surface area available for exchange processes.

Long Descriptions

| Object | Relative Size on Logarithmic Scale |

|---|---|

| Atom | 0.1 nm |

| Lipids | 1.2 nm to 1.4 nm |

| Protein | 1.5 nm to 10 nm |

| Flu Virus | 90 nm |

| Mitochondria | 1 µm |

| Bacteria | 1 µm |

| Animal Cell | 10 µm to 100 µm |

| Plant Cell | 10 µm to 100 µm |

| Human Egg | 400 µm |

| Frog Egg | 1 mm |

| Chicken Egg | 55 mm |

| Ostrich Egg | 90 mm |

| Adult Female Human | 1 m |

Electron microscopes can see between 0.1 nm and 55 µm. Light microscopes can see between 100 nm and 3 mm. The naked eye can see over 100 µm. [Return to Figure 2]

Small Cube measurements:

- Side(s) = 1 cm

- SA = 6 s2 = 6 cm2

- V = s3 = 1 cm3

- SA:V = 6/1 = 6

Large cube measurements:

- Side(s) = 3 cm

- SA = 6 s2 = 54 cm2

- V = s3 = 27 cm3

- SA:V = 54/27 = 2 [Return to Figure 3]

Figure 4 Image Description: The first diagram shows the general parts of the small intestine, including the muscle layers, vessels carrying blood, lumen, and villi. The next diagram zooms in on the villi and shows the different parts, including absorptive cells, capillaries, arteries, veins, and lymphatic vessels. The last diagram zooms in on the absorptive cells to show the microvilli lining it. [Return to Figure 4]

Figure 5 Image Description: Parts of terminal bronchioles include the alveolar sac, alveolar duct, mucous gland, respiratory bronchiole, pulmonary artery, pulmonary vein, capillaries, atrium, and alveolus. [Return to Figure 5]

Figure 7 Image Description: Parts of a neuron include cell membrane, dendrites, cell body (soma), axon, node of ranvier, oligodendrocyte, myelin sheath, and synapse. [Return to Figure 7]

Figure 8 Image Description: Parts of a mitochondrion include the mitochondrial matrix, cristae, outer membrane, and inner membrane. [Return to Figure 8]

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Borrelia hermsii Bacteria (13758011613) by NIAID (2014), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 2: Figure 4.4.1 from LibreTexts General Biology (Boundless) (LumenLearning [was Boundless] 2023) is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Figure 2: Surface Area to Volume Comparison by Hana Zavadska, via CK-12 Foundation, is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 34.12 from OpenStax Biology (Rye et al. 2016) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 2.11 [modification of Alveolus diagram by Mariana Ruiz Villareal in the public domain] from Introductory Animal Physiology (Hinic-Frlog 2019) used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Artistic rendering of motor protein transport of intracellular vesicles. Image credit: Jzp706, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 7: Figure 1 from BCCampus Douglas College Human Anatomy and Physiology II (1st ed.) (Barker 2017) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license. [Original image from OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology (Betts et al. 2013)]

- Figure 8: Figure 4.14 [modification of work by Matthew Britton; scale-bar data from Matt Russell] from OpenStax Biology 2e (Clark et al. 2018) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

Barker JM, editors. 2017. Douglas College human anatomy and physiology II. 1st ed. New Westminster (BC): Douglas College; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/dcbiol12031209/. [Adapted from Human Anatomy and Physiology II by Rice University and OpenStax College].

Barker JM, editors. 2017. Douglas College human anatomy and physiology II. 1st ed. New Westminster (BC): Douglas College; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 12.2: nervous tissue, Figure 1. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/dcbiol12031209/chapter/12-2-nervous-tissue/.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2013. Anatomy and physiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/preface.

Betts JG, Young KA, Wise JA, Johnson E, Poe B, Kruse DH, Korol O, Johnson JE, Womble M, DeSaix P. 2013. Anatomy and physiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 12.8. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/12-2-nervous-tissue.

BioInteractive. Relative sizes of bacteria and viruses | HHMI BioInteractive video [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Nov 9, 1:44 minutes. [accessed 2023 Nov 24]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qGB3cbCBeMg.

Bruslind L. 2019. General microbiology. OR: Oregon State University Ecampus; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://open.oregonstate.education/generalmicrobiology/.

Bruslind L. 2019. General microbiology. OR: Oregon State University Ecampus; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Chapter 3: cell structure. https://open.oregonstate.education/generalmicrobiology/chapter/cell-structure/.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

Clark MA, Choi J, Douglas M. 2018. Biology 2e. 2nd ed. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2023 Sep 28]. Figure 4.14. https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/4-3-eukaryotic-cells.

[GSLC] Genetic Science Learning Center. 2020. Cell size and scale. Salt Lake City (UT): University of Utah; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/cells/scale/.

Hinic-Frlog S, Hanley J, Laughton S. 2019. Introductory animal physiology. Mississauga (ON): University of Toronto; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. http://utmadapt.openetext.utoronto.ca/.

Hinic-Frlog S, Hanley J, Laughton S. 2019. Introductory animal physiology. Mississauga (ON): University of Toronto; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 2.11. http://utmadapt.openetext.utoronto.ca/chapter/2-2/.

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless).

LumenLearning [was Boundless]. 2023. General biology (Boundless). CA: LibreTexts Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 4.4.1. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless)/04%3A_Cell_Structure/4.04%3A_Studying_Cells_-_Cell_Size.

NIAID. 2014. Borrelia hermsii bacteria (13758011613) [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2023 Dec 10; accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Borrelia_hermsii_Bacteria_(13758011613).jpg.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/preface.

Rye C, Wise R, Jurukovski V, DeSaix J, Choi J, Avissar Y. 2016. Biology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 34.12. https://openstax.org/books/biology/pages/34-1-digestive-systems.

Wakim S, Grewal M. 2022. Human biology (Wakim & Grewal). Oroville (CA): Butte College; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Biology/Human_Biology_(Wakim_and_Grewal).

Wakim S, Grewal M. 2022. Human biology (Wakim & Grewal). Oroville (CA): Butte College; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. Figure 5.3.1. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Human_Biology/Human_Biology_(Wakim_and_Grewal)/05%3A_Cells/5.03%3A_Variation_in_Cells.

Waldron I. 2017. Diffusion and cell size and shape [Attached file]. Serendip Studio. [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://serendipstudio.org/exchange/bioactivities/celldiffusion.

Zavadska H. 2017. Figure 2: Surface Area to Volume Comparison [Image]. Palo Alto (CA): CK-12 Foundation; [accessed 2024 Jan 17]. https://www.ck12.org/user:ynv0dgviaw9sb2d5zmfjdwx0eubnbwfpbc5jb20./book/human-biology-butte-17-18/section/5.3/.