3.1 Protein Targeting

Introduction

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION! Different proteins need to be sent to different parts of a eukaryotic cell or, in some cases, exported out of the cell and into the extracellular space. As discussed previously, compartmentalizing cellular functions into separate organelles has many advantages. Each organelle has a unique internal microenvironment that requires a specific set of proteins. However, compartmentalization carries a price. As almost all proteins are coded by nuclear DNA and translated in ribosomes located in the cytosolic space surrounding the nucleus, newly synthesized proteins must be delivered to their respective locations in the cell. After all, what use would a hormone receptor be if it remains localized inside the cell rather than at the surface? The overall question in this Topic is: how do the correct proteins get to the right places?

Nuclear DNA encodes most proteins in the cell, except for just a few mitochondrial or chloroplast proteins coded by mitochondrial or chloroplast DNA, respectively. After transcription and translation, proteins may need to be shipped, or “trafficked,” to specific locations within the cell. When a ribosome begins translating an mRNA, the cell still needs instructions on where to send the new protein so that it may carry out its ultimate function in the correct location. Those instructions are in targeting sequences, also called signal sequences, which consist of specific tags of amino acids appended to the translated protein. Targeting sequences are like subcellular addresses and are specific for the destination, not the protein. For example, all proteins intended for the nucleus carry a homologous Nuclear Localization Sequence. Cellular compartments only accept proteins possessing their respective targeting sequences. Proper recognition by the destination membrane receptors must occur before entry into the organelle. Most targeting or signal sequences are found at the N-terminus of proteins; however, signal sequences can also be found at the C-terminus and in internal locations within the protein. Targeting sequences are present in all precursor proteins except cytosolic proteins. These sequences might later removed from a mature protein or could remain a permanent part of the finished chain.

In this topic, you will learn how targeting/signal sequences determine which of three possible pathways a protein will take within a cell. The importance of this topic to cell and molecular biology is exemplified by the awarding of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Physiology to Günter Blobel for discovering that proteins contain intrinsic signal sequences.

Unit 3, Topic 1 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 3, Topic 1, you will be able to:

- Explain how proteins reach their destinations after transcription and translation.

- Diagram the structure of a nuclear pore and describe its permeability properties.

- Describe the types of signal sequences and their roles in cotranslational and posttranslational protein targeting.

- Compare the mechanisms for importing specific proteins into the nucleus and into mitochondria.

- Relate and draw the topology of transmembrane proteins according to the location and type of signal/transfer sequences.

| Unit 3, Topic 1—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 3, Topic 1 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Protein Review. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: DNA to Protein: Translation. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Protein Translation. | 30 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Posttranslational import. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Translocon. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Protein Translocation. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Topology of transmembrane proteins . | 10 |

No Translocation for Cytosolic Proteins

Every polypeptide begins synthesis the same way: on free cytosolic ribosomes. After mRNA emerges from the nuclear pores with the small ribosomal subunit and initiator complex, the large ribosomal subunit binds to the complex, and translation begins. Codons present in the mRNA select amino acids, resulting in a growing polypeptide chain that exits from a tunnel in the large ribosomal subunit. The exit tunnel physically shelters about 70 amino acids before they are exposed to cytosol when the destination of the protein can be read. The N-terminus of the elongating polypeptide emerges first as the translation continues and immediately folds based on the physical properties of the amino acids. If proteins lack a targeting sequence, the ribosome finishes them, and ribosomal subunits dissociate at the end of translation. Proteins (e.g., glycolytic enzymes, actin, myosin, and tubulin) or intracellular signalling molecules (e.g., protein kinase A) will stay in the cytosol and assume their function. These proteins would immediately fold after production into their final 3D shape and, therefore, their function in the cytosol.

Learning Activity: Protein Review

The following 3D animation reviews how a cell makes proteins from the information in the nuclear DNA code. Before completing this activity, make sure to review the transcription and translation processes before completing this activity.

- Watch the following videos. Make your own notes.

- “From DNA to protein – 3D” (2:41 min) by Yourgenome (2015).

- “DNA and RNA – Transcription” (5:51 min) by Nucleus Biology (2022).

- Answer the following questions:

- What is the purpose of genes?

- Define transcription.

- Which enzyme makes mRNA? What monomers are used to make mRNA?

- What structure reads the mRNA code in the cytoplasm?

- How many amino acids are there? How are they carried to the mRNA strand?

- How does the tRNA ‘know’ which triplet sequence to bind?

- What happens after the tRNA adds the last amino acid?

Learning Activity: DNA to Protein: Translation

- Go to the LabXChange page “DNA to Protein” by The Concord Consortium (2020) and click ‘Start simulation.’

- Click “Transcribe” to zoom into the cell nucleus and see the chromosome unravel to expose the strands of DNA. The DNA separates, and an mRNA strand is created by matching complementary nucleotides. (Press “Transcribe” step-by-step to click through the processes at your own pace.)

- Click “Translate” to watch the mRNA leave the nucleus for the cytoplasm and attach to a ribosome. (Press “Translate” step-by-step to click through the processes at your own pace.) tRNA molecules bring in amino acids, which are added in the correct order by matching complementary nucleotides.

- After translation, inspect the protein to see how the amino acid sequence folded.

Self-Check

Choose which of the following proteins will not have a signal sequence:

- Proteins that remain in the cytosol

- Proteins targeted to the nucleus

- Proteins targeted to the mitochondria

- Proteins targeted to the chloroplast

Show/Hide answer.

a. Proteins that remain in the cytosol

Proteins that do not have a signal peptide stay in the cytosol for the rest of translation. If they lack other “address labels,” they remain in the cytosol permanently. However, if they have the correct labels, they can be sent to the mitochondria, chloroplasts, peroxisomes, or nucleus after translation.

Signal Sequences

Almost all protein synthesis in eukaryotes occurs in the cytoplasm using mRNA generated from genomic DNA found in the nucleus. Exceptions include a few proteins in the chloroplasts and mitochondria that are self-generated using organelle-specific DNA and ribosomes. Proteins found in any other compartment or embedded in any membrane must have been delivered to that location using their signal sequence.

Signal sequences direct the protein from the cytoplasm to a particular organelle. For eukaryotes, specific signal peptides can direct the protein to the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles. Receptors that are soluble or bound to a membrane recognise the signal sequences. For example, receptors are soluble for import into the nucleus; however, receptors are located within the membranes of cellular compartments for delivery to the mitochondria, ER or other organelles. These receptors help guide the insertion of the protein into or through the membrane.

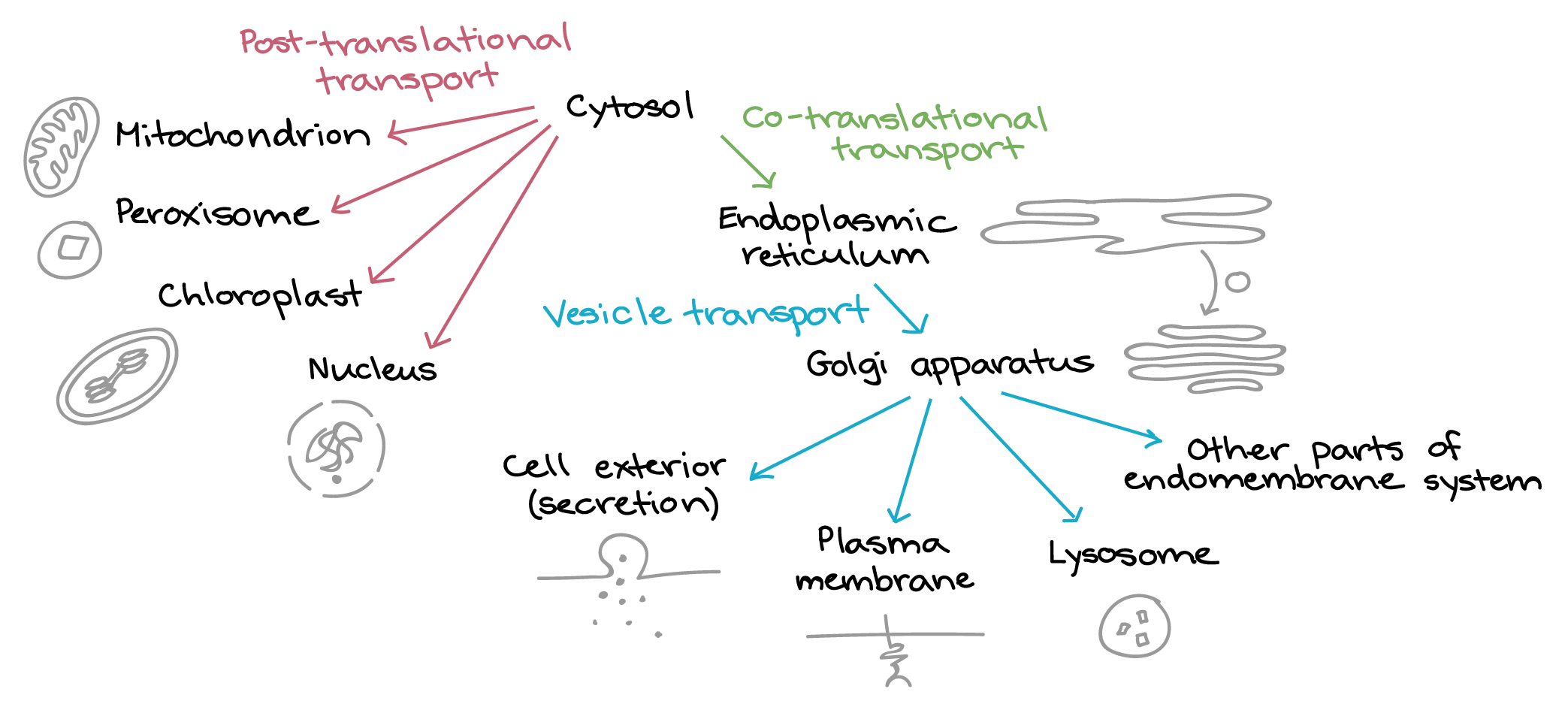

In summary, if the protein has a destination in one of four organelles (nucleus, peroxisome, mitochondrion, or chloroplast), the protein will be finished and released from the ribosome before being trafficked to an address. This process is a type of translocation called posttranslational, as the entire translation precedes the delivery process. In contrast, a protein destined for the ER halts translation on a ribosome until it reaches the ER membrane; the protein then inserts into a pore and translation resumes. This type of translocation is called cotranslational.

Nuclear Localization

Nuclear Import

The nucleus is one organelle that requires protein transportation for proper cell function and growth. For example, the nucleus needs the following proteins: DNA and RNA polymerases, transcription factors, cell cycle regulators, and histones. These and other nuclear proteins have a signal sequence known as the nuclear localization signal (NLS). The NLS is a short stretch of basic amino acids (Pro-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val) exposed on the protein’s surface; it can be located within a protein sequence (monopartite) or split into two separate regions (bipartite). The NLS acts as a signal that helps proteins synthesized in the cytoplasm reach the nucleus to perform their functions; this is a process known as nuclear import. Unlike the signals that target proteins to the RER or mitochondria/chloroplasts, NLSs are not cleaved after import and, thus, remain part of the functional protein.

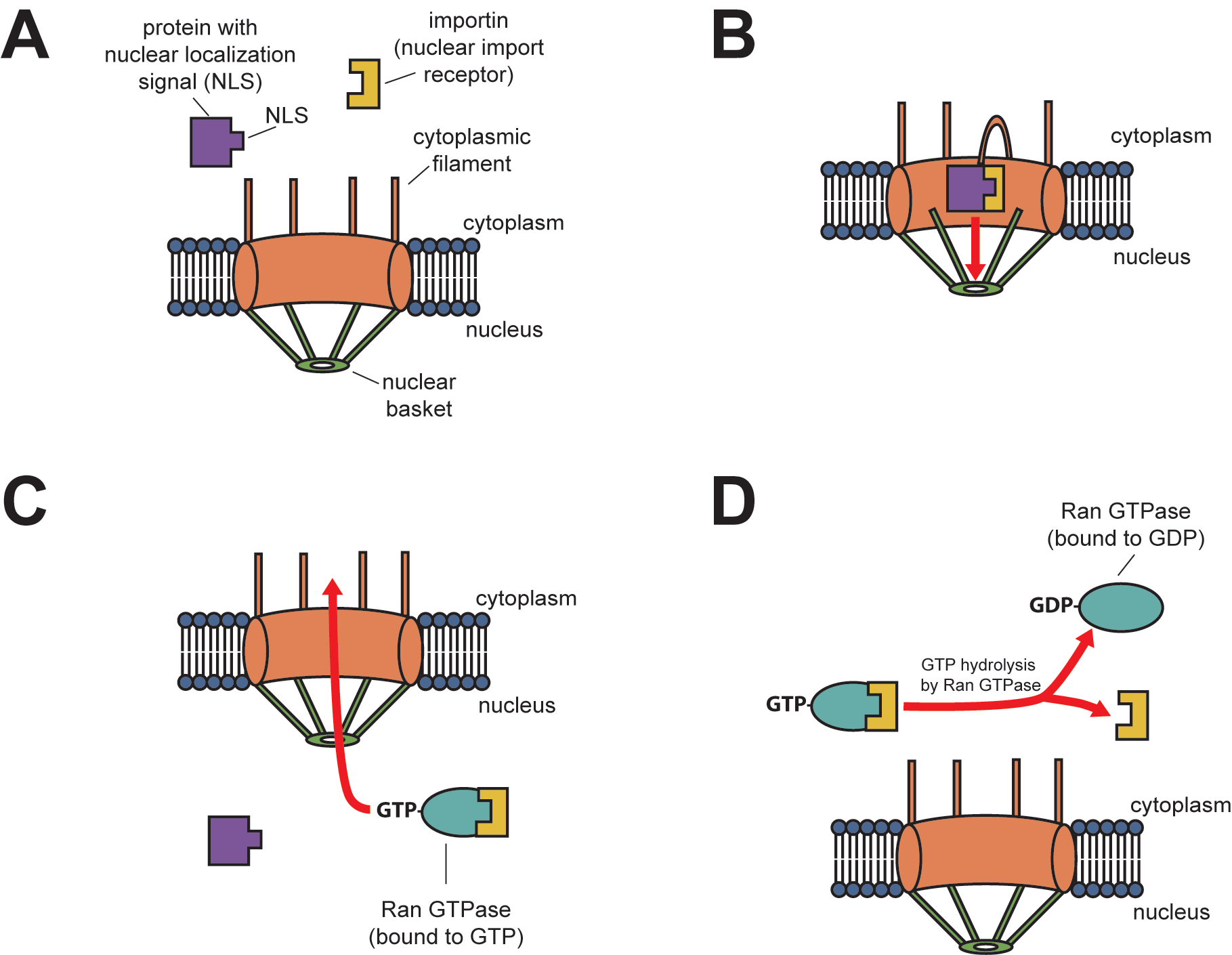

Nuclear localization is a well-studied pathway involving a set of adaptor proteins called importins and the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Figure 1). Transport into the nucleus is particularly challenging because the nuclear envelope is a double membrane contiguous with the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Although there are other mechanisms for making proteins embedded in the nuclear membrane, NPC is the primary mechanism for importing and exporting large molecules in and out of the nucleus. This large complex has over 50 different proteins called nucleoporins (sometimes called “nups”). The nucleoporins assemble into a large open octagonal pore through the nuclear envelope. As Figure 1 indicates, some scaffold nups form antenna-like fibrils on the cytoplasmic face that help guide proteins from their origin in the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Other scaffold nups on the nuclear side form a basket-like structure to help export molecules to the cytoplasm. Yet other nups, called channel nups, form an interior mesh that allows only small molecules to diffuse through.

Translation of a protein containing an NLS completes in the cytoplasm, and the protein folds before nuclear import. For nuclear import to occur, nuclear transport receptors must recognise the NLS. These receptors are members of the importin superfamily, which is important because only they can interact with the nups in the NPC. The importin nuclear transport receptors are soluble, not membrane bound, allowing the cargo protein to bind (the protein gaining entry to the nucleus) and transport the complex through the nuclear pore. While in the cytoplasm, an importin-α protein binds to the NLS of a nuclear protein. Importin-α has an NLS that binds to a protein called importin-β. Thus, importin-α and importin-β together form the complex referred to as the nuclear import receptor (Figure 1A). Importin-β, in particular, is recognised and bound by phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats on the channel nups of the NPC (Figure 1B).

Once the complex of the cargo protein containing the NLS and the importin nuclear transport receptors move into the nucleus, Ran-GTP (a small GTPase) binding causes the protein complex to dissociate (Figure 1C). Both imported cargo protein and importin release into the nucleus; however, Ran-GTP binds to the importin to export it back out through the nuclear pore. Once in the cytosol, Ran hydrolyzes GTP into GDP, providing the energy to dissociate the empty importin from the Ran. Now, the cell can reuse the importin with another cytosolic protein targeted for the nucleus (Figure 1D).

Nuclear Export

Macromolecules can be transported in both directions across nuclear pores. Ran also facilitates nuclear export in a manner that complements nuclear import. Large molecules, such as mRNA, are exported after binding to adaptor proteins tagged with nuclear export signals (NESs). Nuclear transport receptor proteins called exportins recognise such NESs and help them cross the nuclear pore into the cytosol. In nuclear export, Ran-GTP helps exportins bind to the cargo containing NES, which exportins then transport to the cytosol. Once in the cytosol, Ran hydrolyzes GTP into GDP, which causes the cargo to dissociate from the complex.

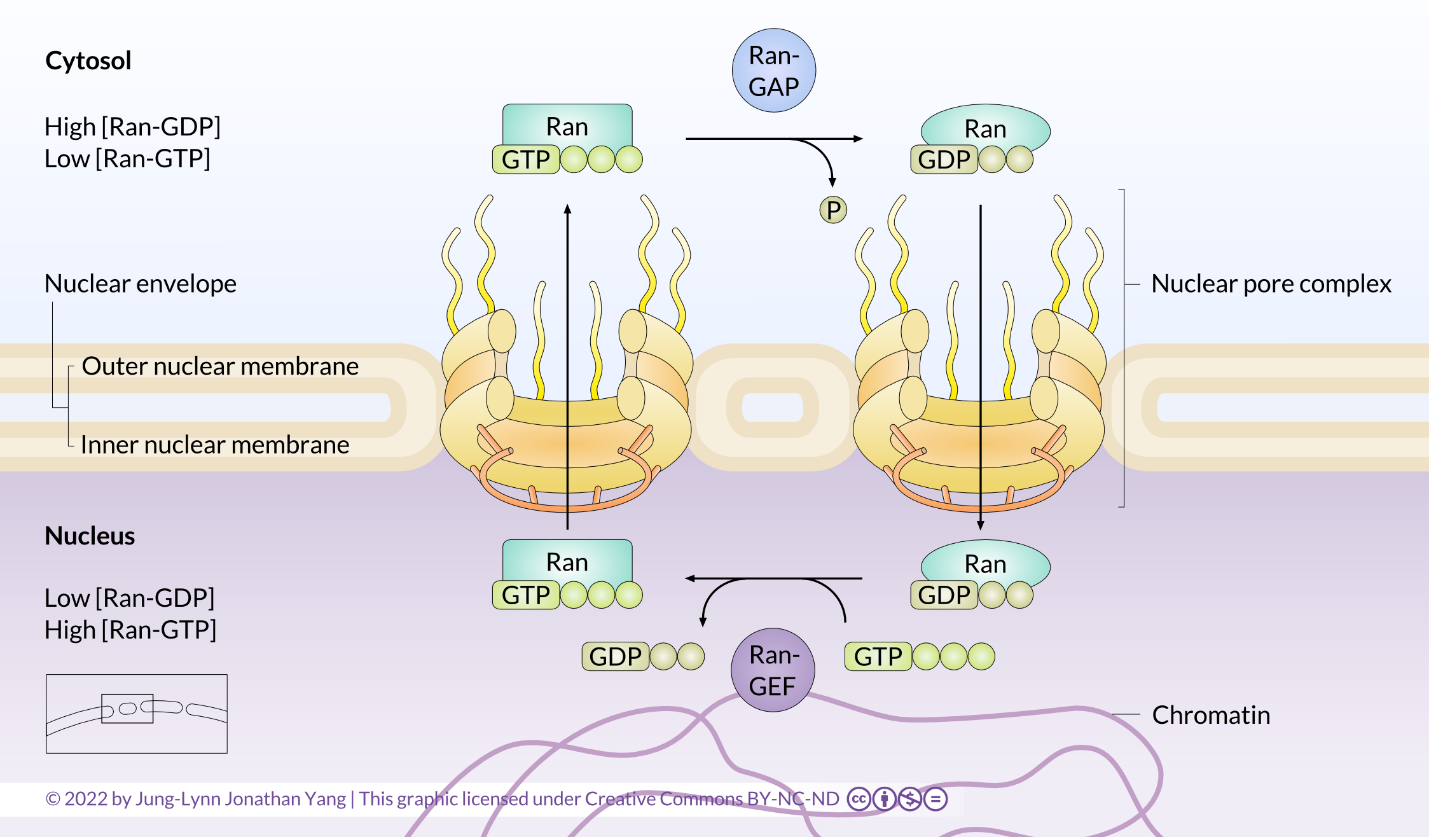

The mechanisms of small GTPase activation in other processes will be discussed again in more detail in later sections on cell signalling. It is important to understand that all small GTPases cycle between GTP- and GDP-bound states, which causes a conformational change in the GTPase. In this way, Ran functions as a molecular switch (Figure 2). The key to understanding this switch mechanism is remembering that the GTPase hydrolyzes GTP to GDP but still holds onto the GDP. Although the GTPase will hydrolyze GTP spontaneously, the GTPase-activating protein, GAP (or Ran-GAP in this case), in the cytosol greatly speeds up the rate of hydrolysis. The GDP is not re-phosphorylated to cycle the system back to GTP; instead, the GDP is exchanged for a new GTP in the nucleus. An accessory protein found only in the nucleus, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) (or Ran-GEF in this case), mainly facilitates this exchange.

Learning Activity: Protein Translation

Animations are helpful in understanding how proteins translated in the cytosol enter and exit the nucleus.

- Watch the following videos. Make your own notes.

- “Basic Structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex” (2:58 min) by Life Science Help (2017).

- “Nuclear Protein Transport” (5:39 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018).

- “Nuclear Import and Export” (4:18 min) by Kasa 0161 (2018).

- “The Nuclear Pore Complex: Nuclear Import, Export, & RAN” (8 min) by Catalyst University (2019).

- “GTPase Function” (5:25 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018).

Self-Check

- Nuclear transport is a passive process that allows large macromolecules like RNA to pass through the nuclear envelope. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. The nuclear pore complex provides two types of nucleocytoplasmic transport: passive diffusion of small molecules and active soluble receptor-mediated translocation of large molecules.

- The nuclear envelope is made of two lipid bilayers separated by the perinuclear space that fuse together to make pores. Scaffold nucleoproteins (nups) allow cargo complexes to bind on both the cytoplasmic and nuclear sides of every nuclear pore. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

True. Some scaffold nups form antenna-like fibrils on the cytoplasmic face that help guide proteins from their origin in the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Other scaffold nups on the nuclear side form a basket-like structure to help export molecules to the cytoplasm.

- Importins are insoluble nuclear transport receptors. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. These receptors must be soluble in the cytosol. The cytosol consists mainly of water, dissolved ions, small molecules, and large water-soluble molecules (such as proteins).

- The importin-RanGTP complex exits the nucleus, and Ran-GAP in the cytosol stimulates RanGTP to hydrolyze its GTP to GDP. This hydrolyzation causes the Ran to undergo a conformational change and, consequently, release the importin. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

True.

- Ran-GAP is restricted to the nucleus, where it can stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. Ran-GAP is restricted to the cytosol, where it maintains a gradient of GTP/GDP-bound Ran. It activates the GTPase function of Ran. This activation allows for the hydrolysis of the third phosphate of GTP-bound Ran. RanGDP is then unable to bind and disrupt the cargo-importin complex.

- Nuclear localization signal sequences are rich in the amino acid leucine. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. NLS are rich in basic amino acids lysine and arginine.

- GTPases, like Ran, can quickly hydrolyze GTP by removing the gamma phosphate group. This hydrolyzation causes a conformational change that deactivates the GTPase, releasing any bound molecules. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. This intrinsic hydrolytic activity occurs very slowly. The presence of a GTPase-activating protein called GAP is required to speed up the reaction.

- What experiment could you do to determine whether the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ran is important in nuclear transport? You could substitute GTP for a nonhydrolyzable analog called GTP-Ɣ-S. This would prevent GEF from helping to hydrolyze Ran’s bound GTP. This would prevent the release of nuclear-bound cargo. True or false?

Show/Hide answer.

False. This would prevent Ran-GAP from helping to hydrolyze Ran’s bound GTP. Cytosolic hydrolysis of RanGTP with the help of Ran-GAP is required for releasing cargo from the importin receptor in the cytosol. There would not be enough free importin receptors for nuclear localization to occur.

Translocation of Peroxisomal Proteins

Consider how proteins are delivered to the peroxisome, an organelle involved in detoxification. The mechanisms guiding peroxisomal protein translocation are very similar to those directing nuclear trafficking. Peroxisomal proteins, such as peroxidase and catalase, are translated and processed in the cytosol. Proteins will fully assume their 3D shape, implying complete functional capacity, before crossing peroxisomal membranes in a process known as posttranslational import.

Peroxisomal targeting sequences (PTS) are on the protein’s N- or C-terminus because they are not needed until a complete protein is available. The classic signal consists of just three amino acids (serine-lysine-leucine) on the protein’s C-terminus of a protein. A helper protein in the cytosol recognises this amino acid pattern and brings the protein to the peroxisome. Peroxisomal transport uses several molecules called peroxins that interact to form functional receptors. Peroxin 5 (Pex5) is a small cytosolic molecule that binds the PTS sequence and delivers the protein to a specific receptor (Pex14) on the peroxisome surface. This receptor opens a translocation channel (made from transmembrane peroxins) and allows the protein to cross into the peroxisome lumen. Pex5 is released on the cytosolic side, ready to bring another molecule. Peroxisomal protein transport differs from transport into the nucleus because the peroxins do not cross the peroxisome membrane.

Mitochondrial Localization

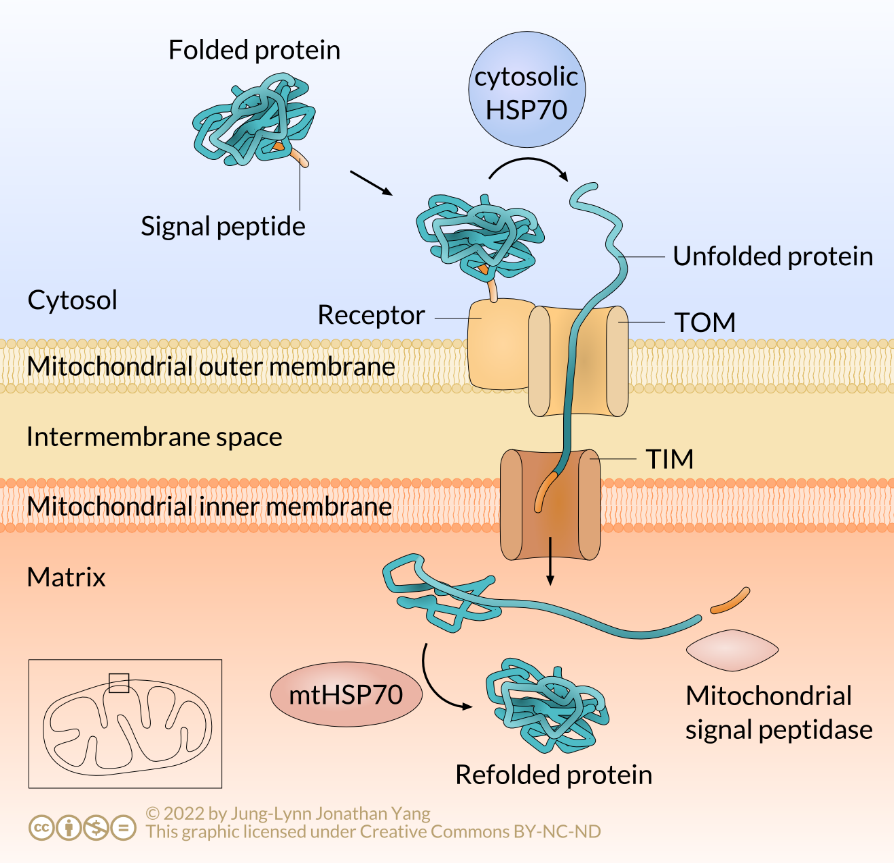

Recall that mitochondria contain their own genome and translational machinery. Thus, they transcribe RNAs and translate their own proteins. However, genes in the nucleus encode many proteins found in mitochondria. Mitochondrial protein transfer is similar to transporting proteins into the nucleus and peroxisomes in that they are both posttranslational. This characteristic means that mitochondrial proteins formed in the cytoplasm have already folded and assumed a tertiary structure. The folded protein exposes an N-terminal signal sequence on its surface that is recognised and bound to a receptor protein embedded in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OM). The receptor protein spans both the OM and membrane of the cristae (CM) (recall mitochondrial cristae as extensive foldings of the inner membrane) (Figure 3).

The cargo protein binding to the receptor protein delivers the protein to membrane contact proteins, which also span both mitochondrial membranes. The membrane contact proteins act as a channel, or pore, through which the mitochondrial protein crosses into the mitochondrial matrix; this is why they are called translocation channels. Mitochondria have two such translocation channels: the translocation channel of the outer membrane (TOM) and the translocation channel of the inner membrane (TIM) (Figure 3). Mitochondrial proteins destined for the intermembrane space pass through TOM, while mitochondrial matrix proteins pass through both TOM and TIM.

For a protein to cross through this translocation channel, it must be unfolded, or linearized, during import and then refolded upon entry into the mitochondrion. However, a problem occurs in that the folded protein cannot cross the membrane by itself. Because of this, a fully translated mitochondrial protein from the cytoplasm requires a so-called chaperone protein to enter the membrane, in this case, the 70 kDa heat-shock protein (HSP70). HSP70 directs the mitochondrial protein to unfold as it passes into the mitochondrial matrix. When a mitochondrial signal peptidase removes the signal peptide, another HSP70 molecule residing in the mitochondrion facilitates the protein to refold into a biologically active shape (Figure 3).

Learning Activity: Posttranslational Import

Posttranslational import across two membranes allows some polypeptides to enter mitochondria and chloroplasts.

- Watch the following videos and make your own notes:

- “Signal Peptide | Cell Signalling” (50 s) by Biotech Review (2014).

- “Cell Bio Mitochondrial Protein Import” (1:32 min) by Grace Cummings (2016).

- “Protein transport into chloroplast” (12:17 min) by Shomu’s Biology (2017).

Self-Check

Do mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own ribosomes?

Hint: how is this related to the endosymbiotic theory?

Show/Hide answer.

Yes, they do. However, these organelles use their internal ribosomes only for some of their proteins. The nucleus hijacks most essential components of the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes. Therefore, most proteins (encoded by the nucleus) are made on ribosomes in the cytosol and imported by mitochondria or chloroplasts after translation.

Go to the resource “Mitochondria and chloroplasts” by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) to review the topic of mitochondria and chloroplasts.

Transport to the ER

The cell targets functional proteins destined for the ER (smooth and rough), the Golgi apparatus, the lysosome, the cell membrane, or secretion from the cell differently than those previously discussed. The following two groups of proteins are targeted to the ER:

- Proteins completely translocated into the ER are soluble (not membrane proteins) and destined for secretion or the lumen of the ER or another organelle.

- Proteins inserted into membranes (only partially translocated into the ER) may be destined for the ER membrane, another organelle’s membrane, or the plasma membrane. In all these cases, the proteins stay embedded in the membrane.

These proteins are targeted to the rough ER early in translation, so they complete translation in the rough ER. Then, they are packaged into vesicles for transport through the Golgi and, finally, sent to their final location. In addition to an ER N-terminal signal sequence directing the ribosome to the rough ER, the position of secondary internal signal sequences (sometimes called signal patches or stop sequences) helps determine the disposition of the protein as it enters the ER.

Cotranslational Import of Soluble Proteins

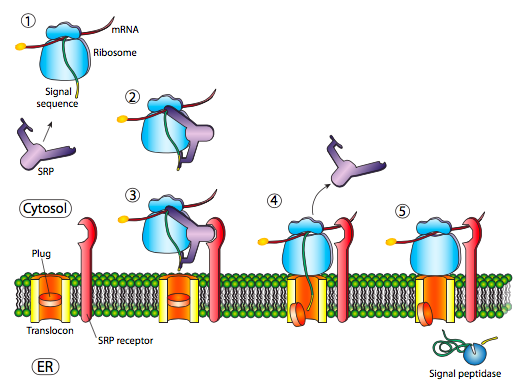

The ER signal sequence is a series of hydrophobic amino acids located at the N-terminal end of the protein. It becomes lodged in the hydrophobic portion of the ER membrane once delivered (Figure 4). ER signal sequences vary from eight to 30 amino acids and typically have a positively charged N-terminal region, a central hydrophobic region that can span the membrane, and a polar region near where the cleavage from the mature protein will take place (+H3N-Met-Met-Ser-Phe-Val-Ser-Leu-Leu-Leu-Val-Gly-Ile-Leu-Phe-Trp-Ala-Thr-Glu-Ala-Glu-Gln-Leu-Thr-Lys-Cys-Glu-Val-Phe-Gln-).

The initial insertion requires the signal recognition particle (SRP) to recognise the ER signal sequence. The SRP is a GTPase that exchanges its bound GDP for a GTP upon binding to a protein’s ER signal sequence. It binds both the ER signal sequence and the ribosome during protein translation. This mechanism differs from the posttranslational one used for nuclear and mitochondrial import. The SRP usually binds as soon as the signal sequence is available, and when it does so, it halts translation until it docks to the ER membrane. The SRP, with its attached protein and ribosome, then docks to a receptor (called the SRP receptor) embedded in the ER membrane and extends into the cytoplasm. Incidentally, this is the origin of the “rough” endoplasmic reticulum: the ribosomes studding the ER attach to the ER cytoplasmic surface during translation by the nascent polypeptide they produce and an SRP.

The SRP receptor can exist alone or in association with a translocon, which contains a translocation channel in the ER membrane. The core of the translocon consists of a Sec61 complex kept closed by a short α helix (called a plug) that prevents Ca2+ from leaking out of the ER. The Sec61 translocon only opens after being bound by the signal sequence; therefore, it acts like a gate. The SRP receptor (SR) is also a GTPase that usually carries a GDP molecule when unassociated. However, upon association with the translocon, it exchanges its GDP for a GTP. These GTPs are essential because both GTPase activities activate when the SRP binds to the SRP receptor, and the resulting energy release dissociates them from the translocon and the nascent polypeptide. This dissociation relieves the block on translation imposed by the SRP, which restarts translation and pushes the new protein through the translocation channel in a linearized or unfolded state during synthesis. This process ensures that translation occurs during translocation and explains why it is called cotranslational translocation.

Once the N-terminal signal sequence fully enters the ER lumen, it reveals a recognition site for signal peptidase. A signal peptidase is a hydrolytic enzyme residing in the ER lumen whose purpose is to snip off the signal peptide. Then, other proteases in the ER membrane and cytosol degrade the signal peptide into amino acids. Note that the N-terminus of the ER-targeted protein is delivered through the translocation channel first, thereby allowing the hydrophobic N-terminal signal sequence to be properly removed prior to protein folding. If the only signal sequence present is the N-terminal signal sequence, the remainder of the protein is synthesized and pushed through the translocation channel. After that, a soluble protein is deposited in the ER lumen (Figure 4).

Learning Activity: Translocon

The following animation provides a visualization of a translocon.

- Watch the animation “Ribosome (ER, mRNA Translation and Translocation)” (50s) by TheDeepSci (2009). Make your own notes.

- Answer the following questions:

- How does the translocator line up with the ribosome?

- Why is this important?

Cotranslational Import of Transmembrane ER Proteins

What about proteins embedded in a membrane? As discussed in Unit 2, transmembrane proteins have one or more α-helical transmembrane segments consisting of 20-30 hydrophobic amino acids. Therefore, one region may be in the cytosol, another embedded within the membrane, and the last may be in the ER lumen. Nevertheless, the same factors that translocate soluble proteins into the ER (e.g., SRP, SRP receptor, and Sec61 translocator) also integrate transmembrane proteins into the ER membrane. This occurs because hydrophobic transmembrane regions are similar to the N-terminal ER signal sequences used for soluble protein translocation.

Single-pass transmembrane segments insert into the ER membrane through one of two general mechanisms discussed below.

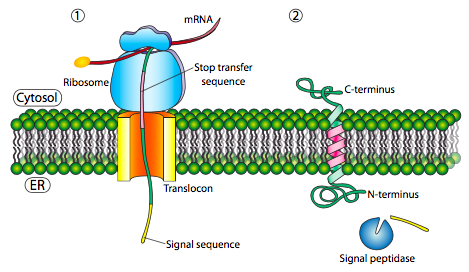

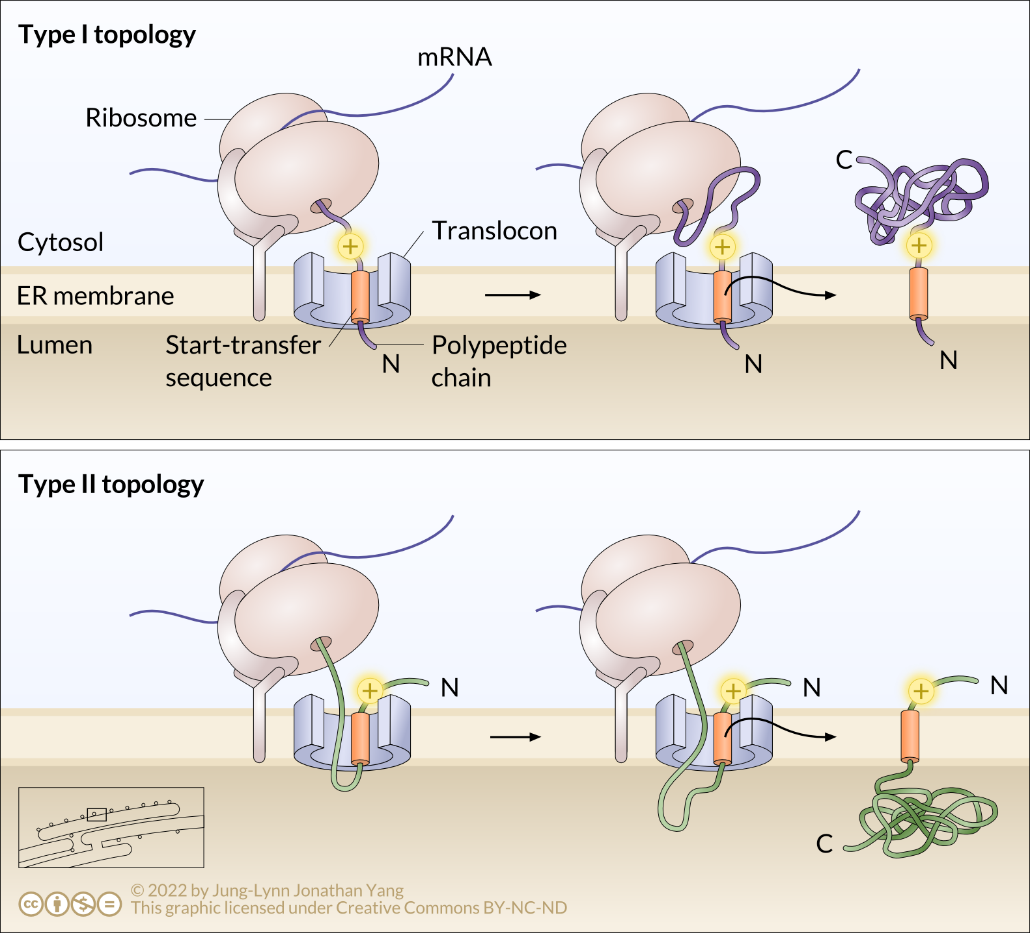

Single-Pass Type I Transmembrane Proteins

The topology of a transmembrane protein refers to where N- and C-termini are on the membrane-spanning polypeptide chain with respect to the inner or outer sides of the biological membrane occupied by the protein (Figure 5). The topology of transmembrane proteins depends on the relative locations of various hydrophobic amino acid regions.

Some polypeptides contain N-terminal signal sequences similar to those of soluble proteins used to initiate translocation, as discussed above. This sequence targets the N-terminus to the ER lumen (Figure 5). A significant stretch of mostly uninterrupted hydrophobic residues after the signal sequence is known as a stop-transfer signal because that part of the protein can get stuck in the translocation channel (and subsequently the ER membrane), which forces the remainder of the protein to remain outside the ER. This signal generates a single-pass Type I transmembrane protein that inserts into the membrane once. The topology of this protein consists of the N-terminus in the ER lumen and the C-terminus in the cytoplasm.

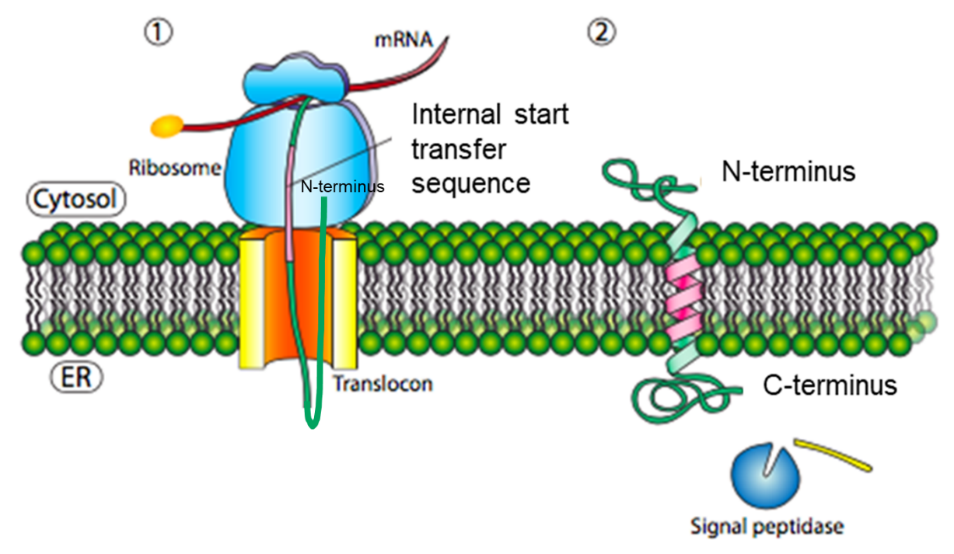

Single-Pass Type II Transmembrane Proteins

In other cases, a protein can synthesize without a typical ER signal sequence at the N-terminus. Such a polypeptide begins synthesis, and then SRP recognises an internal hydrophobic start-transfer sequence once it emerges from the ribosome during translation. SRP recognises this as a signal sequence and targets it to the Sec61 translocator in the ER membrane. This hydrophobic start-transfer sequence effectively acts as an anchor to form the transmembrane domain that moves out laterally from the translocon side opening. The resulting protein is a Type II transmembrane protein (Figure 6). Therefore, the topology of a Type II protein consists of a cytosolic N-terminus and a luminal C-terminus.

In addition, positively charged amino acids related to the start-transfer sequence can influence the topology of Type II transmembrane proteins (Figure 7).

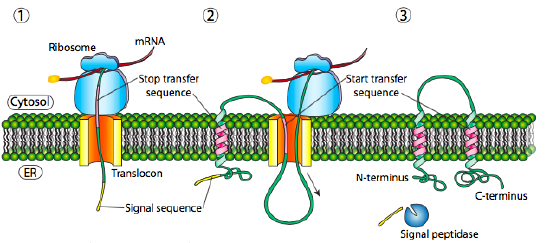

Multipass Transmembrane Proteins

A multipass transmembrane protein can have a signal peptide and several start- and stop-transfer hydrophobic signal patches. Building on the single-pass Type I example, the presence of a hydrophobic signal patch (a stop-transfer sequence) after the initial signal sequence would attach to the Sec61 channel and move laterally into the lipid bilayer. As translation proceeds, the presence of another hydrophobic signal patch (a start-transfer sequence) would get stuck in the Sec61 channel again while the remainder of the protein would move into the ER lumen. The topology of this protein would be described with both N- and C-termini in the ER lumen, passing through the ER membrane twice with a cytoplasmic loop sticking out into the cytosol (Figure 8).

It is important to note that other configurations for single-pass and multiple-pass membrane proteins are possible. The examples shown here do not indicate all the potential membrane protein configurations.

Learning Activity: Protein Translocation

The endoplasmic reticulum play an important role in protein synthesis. The order of events that occur during cotranslational translocation is important.

- Watch the following animations showing how signal peptides direct proteins to the ER membrane. Make your own notes.

- “Protein Translocation” (4:31 min) by Richard Posner (2015).

- “Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein Transport” (7:14 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018).

- Complete the following exercise:

Three steps of cotranslational translocation are listed below (1, 3, 5). List or briefly describe two events (2 and 4) that occur between steps 1, 3 and 5 listed below.

1. The N-terminal ER signal sequence is synthesized on a ribosome.

2. ✐▒

3. The ribosome, polypeptide and SRP complex bind to the SRP receptor in the ER membrane near the translocon. GDP is exchanged for GTP to unblock translation.

4. ✐▒

5. Cleavage of the protein by signal peptidase occurs. The soluble protein is deposited in the ER lumen.

Self-Check

Consider an mRNA that encodes a protein with an N-terminal ER signal sequence. What would happen to cotranslational translocation if SRP was missing? (Assume all other relevant components are present.)

- Protein translation would be completed, and the protein would be found in the cytosol (protein product is longer than usual).

- Protein translation would be completed, and the protein would be in the lumen (protein product is its usual length).

- Protein translation would not begin.

- Protein translation would be completed, and the protein would be found in the cytosol (protein product is its usual length).

- Protein translation would begin but be paused indefinitely (protein product is shorter than usual).

Show/Hide answer.

a. Protein translation would be completed, and the protein would be found in the cytosol (protein product is longer than normal).

The SRP usually binds as soon as the signal sequence is available, and when it does so, it also binds the ribosome, halting any further translation until it docks to the ER membrane. Therefore, translation would proceed in the absence of SRP using resources present in the cytosol. The protein is longer than usual because the signal peptide is not cleaved.

Learning Activity: Topology of Transmembrane Proteins

In this activity, you will practice identifying the topology associated with various signal and transfer sequences.

- Watch this animation about transmembrane topology I from Cell Physiology by Malgosia Wilk-Blaszczak (2019) and answer the following questions.

- What is the topology and type of transmembrane protein depicted in this animation?

- What signal and/or transfer sequences does it have?

- Watch this animation about transmembrane topology II from Cell Physiology by Malgosia Wilk-Blaszczak (2019) and answer the following questions.

- What is the topology and type of transmembrane protein depicted in this animation?

- What signal and/or transfer sequences does it have?

Key Concepts and Summary

Translation of all proteins in a eukaryotic cell begins on free ribosomes in the cytosol (except for a few proteins made in mitochondria and chloroplasts). Making a protein involves passing it step-by-step through a shipping “decision tree.” The protein is checked at each stage for molecular tags to see if it needs to be re-routed to a different pathway or destination. The first key branch point comes soon after the translation starts. At this point, the protein either remains in the cytosol for the rest of the translation (if it lacks a targeting signal) or takes the following routes will be taken (Figure 9):

- A protein may contain information in amino acid sequences that serve as an address or targeting signal. All proteins targeted to the same destination (e.g., nucleus) carry the same address signal encoded in their protein sequence.

- Some proteins are directed to various organelles. This process involves posttranslational import after the complete translation of the protein.

- Other proteins are directed to the ER/Golgi system, where vesicles transport them for secretion from the cell or to the plasma membrane, lysosomes or other parts of the endomembrane system. This process involves cotranslational import before the complete translation of the protein.

- A specific protein receptor corresponds to each type of targeting signal. It binds only to the correct targeting signal sequence. This second part of the system corresponds to the street addresses on buildings in a city. Such buildings include cellular organelles, such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, chloroplasts, endoplasmic reticulum, and the nucleus.

Cotranslational ER targeting

Proteins are fed into the ER during translation if they have an amino sequence called an N-terminal signal peptide and/or internal start-transfer sequence. This process is called cotranslational import. In general, proteins bound for organelles in the endomembrane system (such as the ER, Golgi apparatus, and lysosome) or for the exterior of the cell must enter the ER at this stage. There are three types of hydrophobic signals used to insert ER membrane proteins. These include the following membrane-spanning domains:

- Signal peptide sequence — A cluster of about 8–10 hydrophobic amino acids at the N-terminal end of a protein. This sequence is cleaved off the protein after transfer through the membrane into the ER lumen.

- Start-transfer sequence — This is like a signal sequence, but it is located internally (not at the N-terminal end of the protein). It also binds to the signal recognition particle (SRP) and initiates transfer. Unlike the N-terminal signal sequence, it is not cleaved after transferring the protein.

- Stop-transfer signal sequence — This is also a sequence of about eight hydrophobic amino acid residues. It follows either an N-terminal signal sequence or a start-transfer sequence.

- The stop-transfer signal is also a membrane-spanning domain. Therefore, it remains in the membrane.

- The translocation channel opens when it encounters the stop-transfer signal.

- The peptide is not cleaved.

- Translation continues in the cytoplasm.

- If it encounters a subsequent start-transfer sequence in the protein, a second SRP binds to the start-transfer sequence, and a new translocation channel opens in the membrane.

Posttranslational targeting

Proteins that do not have a signal peptide stay in the cytosol for the rest of translation. If they lack other “address labels,” they remain in the cytosol permanently. However, if they have the correct labels, they can be sent to the mitochondria, chloroplasts, peroxisomes, or nucleus after translation. Therefore, import into the mitochondrion, peroxisome, chloroplast, and nucleus after protein translation is called posttranslational transport.

Nuclear targeting

The nuclear envelope contains many nuclear pores that regulate the two-way transport of macromolecules between the nucleoplasm and cytosol. Soluble receptors, called importins and exportins, and a concentration gradient of Ran-GTP regulate the transport direction.

The following points summarize the nuclear import process:

- The nuclear localization signal (NLS) is a short sequence of basic amino acids that can be located in one region within a protein sequence (monopartite) or split into two separate regions (bipartite) that bind to the importin-α nuclear transport receptor.

- The cargo–importin-α complex binds to importin-β, the latter of which binds to the FG repeats of the fibrils that extend on the cytosolic side of the nuclear pore complex. This interaction is specific and depends on the nuclear import receptor binding to the NLS protein.

- The nuclear pore apparatus transfers the nuclear import receptor-NLS protein complex into the nucleus.

- Once in the nucleus, Ran-GTP binds to the nuclear import receptor and causes it to detach from the NLS protein. The empty nuclear import receptor and Ran-GTP return to the cytosol.

- Once back in the cytosol, Ran-GAP triggers Ran-GTP to hydrolyze its bound GTP. Ran-GDP can no longer bind the importin receptor, freeing it to bind more NLS-containing cargo and another cycle of nuclear import.

- Ran functions as a molecular switch and undergoes a conformational change between the GDP- and GTP-bound states, with the aid of a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (Ran-GEF) in the nucleus and a GTPase-activating protein (Ran-GAP) in the cytosol.

Nuclear export differs from import in the following ways:

- Nuclear export involves similar mechanisms as nuclear import but primarily involves RNA molecules as the cargo.

- RNA binds to adaptor proteins, whose nuclear export sequences (NESs) are recognised by the nuclear transport receptor proteins called exportins with the help of Ran-GTP.

The restriction of Ran-GEF in the nucleus and Ran-GAP in the cytosol provides directionality to nuclear import and export. The high nuclear concentration of Ran-GTP ensures the following two events:

- Nuclear Ran-GTP dissociates the imported NLS-containing protein from importins.

- Nuclear Ran-GTP helps the binding of NES-containing cargo to exportins.

Targeting of proteins to mitochondria, chloroplasts or peroxisomes

- The protein containing the signal sequence synthesizes in the cytoplasm.

- The signal sequence binds to a receptor in the organelle membrane.

- The receptor-protein complex diffuses within the membrane to a contact site.

- The protein is unfolded, moves across the membrane, and refolds. These events are carried out by the protein transporter complex and associated chaperone proteins, including HSP70. The signal sequence is the first part of the protein to enter the organelle.

- Once inside, the signal sequence is cleaved off by a specific peptidase.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 9-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: The Ran-GTP/Ran-GDP cycle by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Posttranslational import of proteins into the mitochondrion by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: Figure 9-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Figure 9-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 9-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is modified and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Integration of a Type II single-pass transmembrane protein… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 9-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is modified and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Overview of cellular shipping routes [based on similar diagram in Alberts et al.] by Khan Academy ([date unknown]) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Alberts B, Heald R, Johnson A, Morgan D, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P, Wilson J, Hunt T. 2022. Molecular biology of the cell. 7th ed. New York (NY): W. W. Norton & Company.

Biotech Review. Signal peptide | cell signalling [Video]. 2014 Mar 14, 0:49 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=epywovT_S9I.

Catalyst University. The nuclear pore complex: nuclear import, export, & RAN [Video]. YouTube. 2019 Apr 14, 8:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYMoP_dAXsI.

Cell Bio Clips. GTPase function (regulatory proteins) [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Oct 18, 5:25 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eohda8jt7KM.

Cell Bio Clips. Endoplasmic reticulum protein transport (cytoplasm to ER and ER to cytoplasm) [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Oct 23, 7:14 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TmQKHHB51P8.

Cell Bio Clips. Nuclear import and signal hypothesis [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Nov 27, 5:39 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RDUUngYhRiU.

Farcciotti M. 2019. Introductory biology. Davis (CA): University of California, Davis; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/LibreTexts/University_of_California_Davis/BIS_2A%3A_Introductory_Biology_(Facciotti).

Farcciotti M. 2019. Introductory biology. Davis (CA): University of California, Davis; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. W2017_lecture_21_reading, Protein synthesis. https://bio.libretexts.org/LibreTexts/University_of_California_Davis/BIS_2A%3A_Introductory_Biology_(Facciotti)/Readings/W2017_Readings/W2017_Lecture_21_reading.

Grace Cummings. Cell bio mitochondrial protein import [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Nov 21, 1:32 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J9EWTI5m2mM.

Hardin J, Bertoni G. 2016. Becker’s world of the cell. 9th ed. London (England): Pearson.

Kasa 0161. Nuclear import and export [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Apr 17, 4:21 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGPpKk-6-K0.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 9: protein trafficking. Figures 9-1 to 9-5. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/92527ecb-306c-4002-a411-e3c5d5da5e6a.

Khan Academy [date unknown]. Mitochondria and chloroplasts. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jul 23]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/structure-of-a-cell/tour-of-organelles/a/chloroplasts-and-mitochondria.

Khan Academy [date unknown]. Protein targeting. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2022 Jul 23]. Figure overview of cellular shipping routes. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/gene-expression-central-dogma/translation-polypeptides/a/protein-targeting-and-traffic.

1 LeBrasseur N. 2003. Ran sticks a GEF chromatin. J Cell Biol. 160(5):625. https://rupress.org/jcb/article/160/5/625/33211/Ran-sticks-a-GEF-to-chromatin. doi:10.1083/jcb1605iti5.

Life Science Help. Basic structure of the nuclear pore complex [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Mar 21, 2:58 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gor7LyF65oo.

Nucleus Biology. DNA and RNA – transcription [Video]. YouTube. 2022 Mar 21, 5:51 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlOqI3PQwjo.

Richard Posner. 12 5 protein translocation [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Jul 6, 4:31 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUY3dSSthfE.

Shomu’s Biology. Protein transport into chloroplast [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Mar 29, 12:17 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tltnKdNt0Y.

The Concord Consortium. 2020. DNA to protein [interactive simulation]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [acccessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/pathway/lx-pathway:ad7fbf7e-9fee-4989-b8c6-e5737d21cc91/items/lx-pb:ad7fbf7e-9fee-4989-b8c6-e5737d21cc91:lx_simulation:8ee49d63.

TheDeepSci. Ribosome (ER, mRNA translation and translocation) [Video]. YouTube. 2009 May 27, 0:50 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eYuypGVAU_Y.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Membrane topology. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Oct 25; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Membrane_topology&oldid=1181800714.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Protein targeting. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Dec 25; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Protein_targeting&oldid=1191809893.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. TIM/TOM complex. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Jan 13; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=TIM/TOM_complex&oldid=1133339799.

Wik-Blaszczak M. 2019. Cell physiology. Arlington (TX): University of Texas Arlington; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. Distribution of proteins to sub-cellular components. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/cellphysiology/chapter/distribution-of-proteins-to-sub-cellular-compartments/.

Wik-Blaszczak M. 2019. C-terminal outside protein translocation [animation]. Arlington (TX): University of Texas Arlington; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/52/2019/02/1.3-C-terminal-outside-protein-translocation.mp4?_=4.

Wik-Blaszczak M. 2019. N-terminal outside protein translocation [animation]. Arlington (TX): University of Texas Arlington; [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/52/2019/02/1.3-N-terminal-outside-protein-translocation.mp4?_=5.

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 11.2: protein trafficking. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong)/11%3A_Protein_Modification_and_Trafficking/11.02%3A_Protein_Trafficking.

Yang J-L J. 2022. Figure 2, 3, 7 created for this course.

Yourgenome. From DNA to protein – 3D [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Jan 7, 2:41 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG7uCskUOrA.