3.4 The Cytoskeleton

Introduction

What would happen if someone snuck in during the night and stole your skeleton? Biologically speaking, it is unlikely, but assuming it somehow did happen, losing your skeleton would cause your body to lose much of its structure. Your external shape would change, some of your internal organs might start moving out of place, and you would probably find it very difficult to walk, talk, or move.

The same is true for a cell. People often imagine cells as soft, unstructured blobs, but cells are actually highly structured in much the same way as human bodies. Cells have a network of filaments collectively known as the cytoskeleton (literally, “cell skeleton”). Not only does the cytoskeleton support the plasma membrane and give the cell an overall shape, but it also aids in the correct positioning of organelles, provides tracks for the transport of vesicles, and (in many cell types) allows the cell to move. Unlike a human skeleton, made of bone, the cytoskeleton is highly dynamic and internally motile, shifting and rearranging in response to the needs of the cell. The cytoskeleton also has a variety of purposes beyond simply providing the shape of the cell. Generally, these functions can be categorized as structural and transport.

Unit 3, Topic 4 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 3, Topic 4, you will be able to:

- Describe the major functions of the cytoskeleton and its role in determining cell shape, positioning of organelles, intracellular trafficking, and cell movement.

- Identify, describe, and draw the structure and function of microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules.

- Compare and contrast the three types of cytoskeletal elements (microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules) with respect to monomers, polymerization, and dynamics.

| Unit 3, Topic 4—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 3, Topic 4 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: The cytoskeleton—a preview. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Intermediate filaments I. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Intermediate filaments II. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microfilaments. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Treadmilling in more detail. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell crawling. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microfilaments and lymphocyte motility. | 7 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary of intermediate and microfilaments. | 7 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microtubule (MT) structure and formation. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microtubules, dynamic instability, and the effects of GTP/GDP. | 7 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microtubules—Do I shrink or do I grow? | 20 |

Cytoskeletal Fibres

The cytoskeleton is a network of different protein fibres that provide many functions. It maintains or changes the cell shape, secures some organelles in specific positions, enables the movement of cytoplasm and vesicles within the cell, and enables the cell to move in response to stimuli.

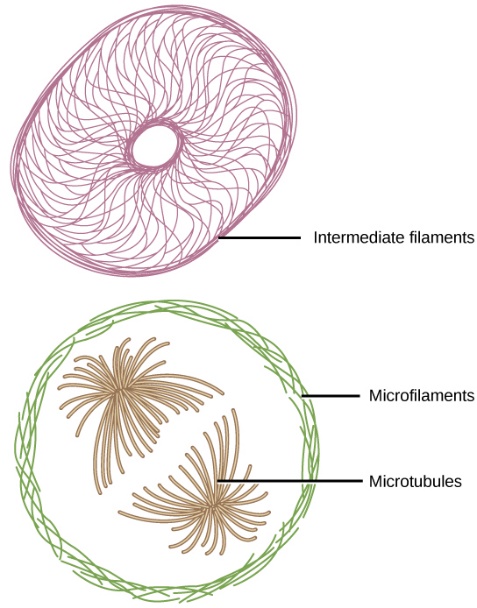

In eukaryotes, there are three types of protein fibres in the cytoskeleton: microfilaments (also called actin filaments), intermediate filaments, and microtubules. Topic 4 will examine each type of filament and some specialized structures related to the cytoskeleton. Some cytoskeletal filaments work in conjunction with molecular motors that move along the filaments within the cell to carry out a diverse set of functions (Figure 1).

From a physical standpoint, the microtubule is strong but not very flexible. A microfilament will flex and bend when a deforming force is applied (imagine the filament anchored at the bottom end standing straight up and something pushing the tip to one side). A microtubule in that same situation will only bend slightly but break apart if the deforming force is sufficient. There is, of course, a limit to the flexibility of the microfilament, and eventually, it will also break. Intermediate filaments are slightly less flexible than microfilaments but can resist far more force than either microfilaments or microtubules.

Learning Activity: The Cytoskeleton — A Preview

- Watch the video “The cytoskeleton” (6:52 min) by Khan Academy (2015) for a preview of the cytoskeleton.

- Make your own notes on the relative sizes of the various cytoskeletal filaments.

- Write down any questions that you may have so that you can clear them up as you progress through the Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the Learning Activities.

Intermediate Filaments

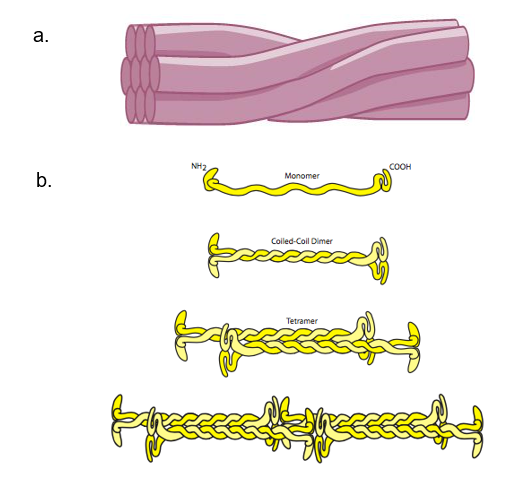

Intermediate filaments consist of several fibrous protein strands wound together. They are the most diverse group of cytoskeletal elements. Intermediate filaments come in many types, with diameters between microtubules and microfilaments. Therefore, they are called “intermediate” filaments. One example of an intermediate filament is keratin, which has a diameter of 8–12 nm (Figure 1c). Keratin is the fibrous protein that strengthens hair, nails, and the epidermis of the skin. Intermediate filaments are rope-like proteins made of filamentous monomers twisting together to provide strength (Figure 2a).

Intermediate filaments have no role in cell movement. Their function is purely structural. They bear tension, providing tensile strength, which is the strength to help a cell withstand mechanical stress. Therefore, they help maintain the cell shape and anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place. The basic unit of intermediate filament structure is a dimer of monomers called a coiled coil. The dimers are staggered together, generating tetramers. Tetramers bind together to form twisted protein strands that provide tensile strength to cells (Figure 2b). The most striking characteristic of intermediate filaments is their relative longevity. Once made, they change and move very slowly. They are very stable and do not break down easily. They are not usually totally inert, but compared to microtubules and microfilaments, they sometimes seem to be.

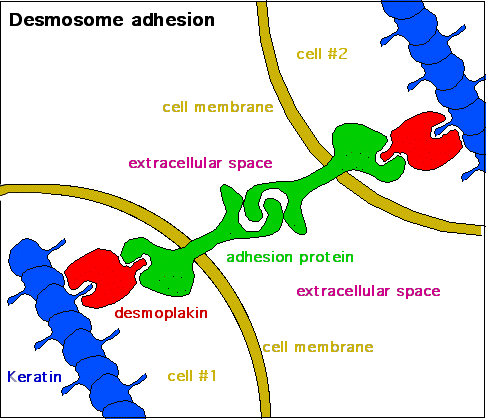

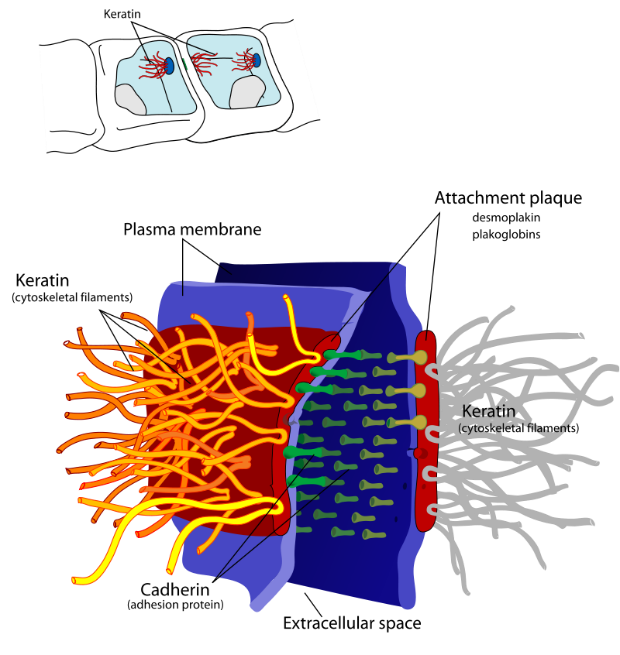

Keratin

Skin cells have a high concentration of the intermediate filament keratin. Keratin forms a mesh-like network throughout cells. Additionally, these keratin networks connect to keratin networks of adjacent cells via keratin fibre bundles in a cellular adhesion structure called a desmosome (Figure 3). Desmosomes are necessary for structural integrity in the epithelial layers and are the most common cell-cell junction in such tissues. Due to desmosomes, pressure that may burst a single cell can be spread over many cells, sharing the burden and thus protecting each member. Therefore, keratin provides tensile strength to skin cells, allowing them to move together as a sheet rather than separating in response to mechanical stressors (like a pinch).

Figure 3: (Left) Desmosomes are cell adhesion structures between two neighbouring cells, which connect keratin from one cell to the keratin of a neighbouring cell using a series of adaptors and adhesion proteins. (Right) A labelled diagram of a desmosome junction between two membranes. It shows the key molecular components that allow desmosomes to tightly link two adjacent cells. Left: (Katzman et al. 2020/Fundamentals of Cell Biology) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Right: (Ruiz 2007/Wikimedia Commons) Public Domain

Loss-of-function mutations in keratins lead to individual cells being unable to maintain structural integrity under pressure. Mutations in keratin genes can lead to conditions collectively termed epidermolysis bullosa, in which the skin is extraordinarily fragile, blistering, and breaking down with only slight contact. This fragility compromises the patients’ first line of defense against infection: the skin (Figure 4).

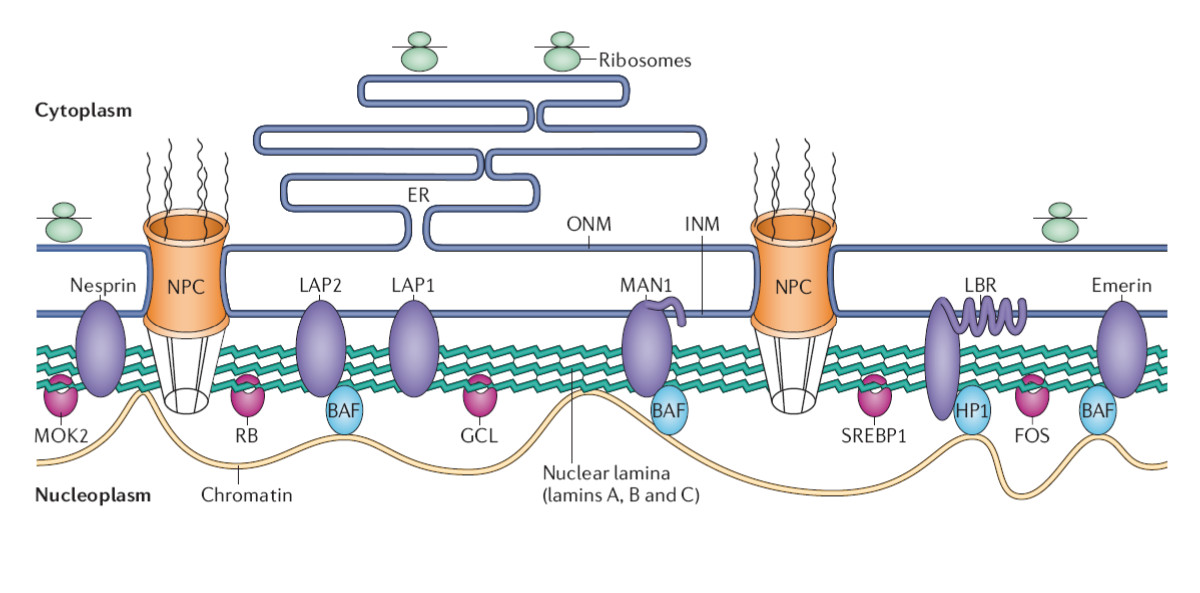

Lamins

Lamins are another type of intermediate filament. They make up structural elements of the nuclear lamina, a kind of nucleoskeleton. The nuclear lamina is located just inside the nuclear envelope and is essential in maintaining its structure (Figure 5).1,2

The nuclear lamina also plays an important role in cellular functions like mitosis, where the nuclear envelope breaks down during prophase and reforms during telophase. Notably, defects in nuclear lamin proteins have been associated with progeria. Figure 6 demonstrates the structure of the nuclear lamin from healthy patients (top right) compared to those isolated from progeria patients (bottom right). As shown, progeria patients have irregularly shaped nuclear envelopes. These irregularities are associated with defects in mitosis, which cause premature aging in patients with these lamin defects (left panel).

Self-Check

Drag the correct term for each cytoskeletal structure shown in the figure.

Learning Activity: Intermediate Filaments I

- Watch the video “Intermediate Filaments (Structure and Function)” (3:37 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What is the primary function of intermediate filaments?

- What are intermediate filaments made of?

- Describe the formation of intermediate filaments. Draw the structure.

- What composes a protofilament? Label your drawing above.

- What composes a protofibril? Is it flexible?

- Where are such protofibrils found? Why?

- How many groups of microfilaments are there? List at least three of their functions and provide an example.

Learning Activity: Intermediate Filaments II

- Watch the video “17 1 Intermediate Filaments” (2:28 min) by Ryan Abbott (2017).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- Draw the structure of a coiled-coil dimer.

- Draw a staggered tetramer.

- Draw two linked tetramers.

- How many tetramers twist into a rope-like intermediate filament?

- Explain what gives intermediate filaments their remarkable mechanical strength.

Microfilaments (Actin Filaments)

Structure and Assembly

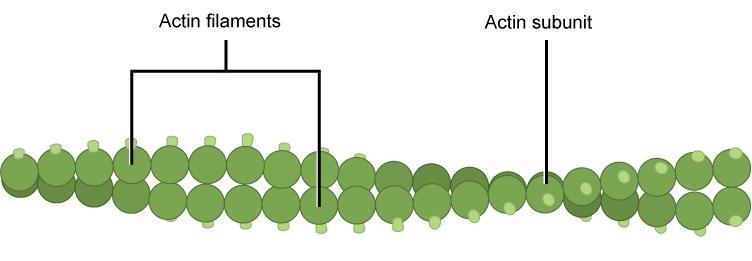

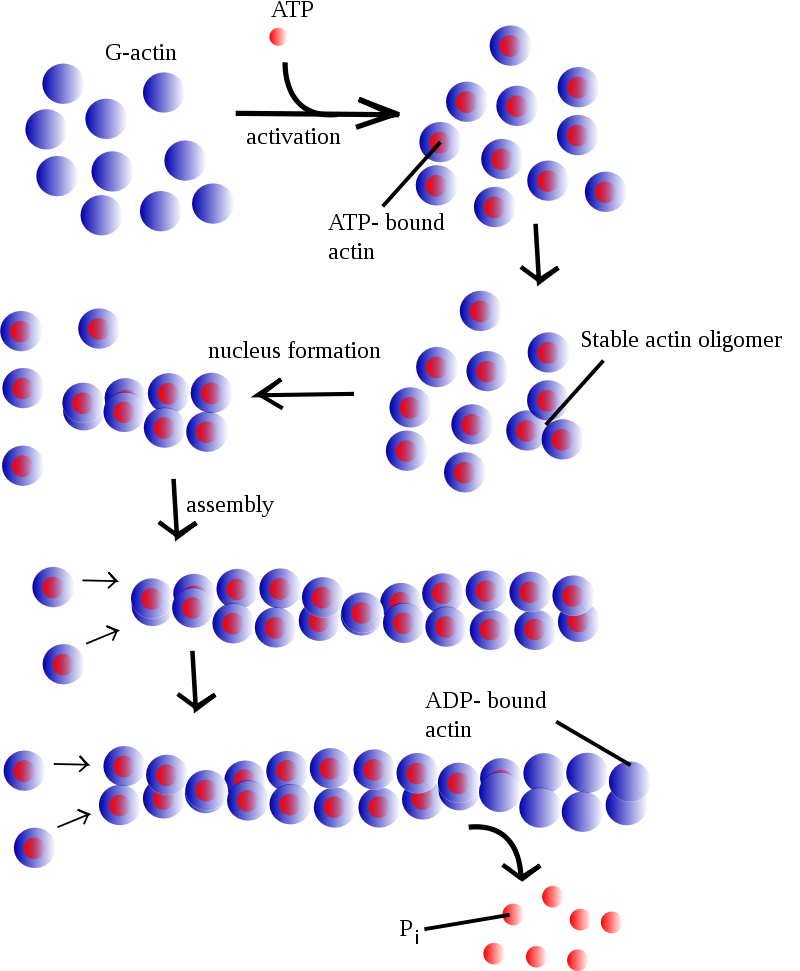

Microfilaments (also called actin filaments) are cytoskeleton fibres composed of actin subunits. Microfilaments are the thinnest type of cytoskeleton, with a diameter of 7 nm (Figure 1b). Actin is one of the most abundant proteins in eukaryotic cells. Actin can be present as either a free monomer that is globular (G-actin) or bound together in a helical polymer (filamentous actin or F-actin) (Figure 7). Individual microfilaments can exist, but most microfilaments in vivo are twisted pairs. Unlike DNA, however, microfilament pairs are not antiparallel, as both strands have the same directionality.

Microfilaments consist of small G-actin subunits stacked on one another with relatively small contact points. They are similar to two tennis balls, one fuzzy and the other covered in Velcro hooks. In both cases, pushing hard on the balls to squish them together will not change the fact that the area of contact between the balls (i.e., the area available for hydrogen bonding between subunits) is relatively small compared to the overall surface area. Furthermore, the balls will hold together but can also fall apart with little force. Contrast this with intermediate filaments that are more like two ribbons of Velcro hooks or loops. Considerably more work is required to take them apart. Because there are fewer hydrogen bonds to break, the microfilaments can deconstruct very quickly, making them suitable for highly dynamic applications.

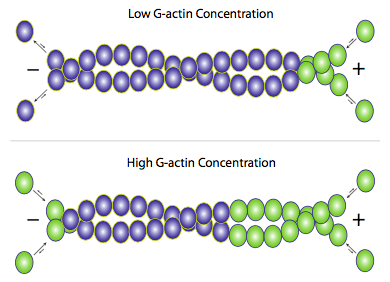

The actin filament itself has structural polarity (Figure 8). This term “polarity” refers to the fact that there are two distinct ends to the filament. These ends are called the minus (−) end and the plus (+) end, but this only applies to directionality and has nothing to do with electrical charge. At the plus end, actin subunits are adding onto the elongating filament, and at the minus end, actin subunits are disassembling or falling off the filament. The ability of the actin filament to assemble and disassemble, thereby changing its length, is termed dynamic instability. This dynamic instability is integral for some cellular functions, including cell crawling, which depends on rapid actin polymerization and depolymerization. Dynamic instability is also a characteristic of microtubules as you’ll see in a later section of Topic 4.

Forming filaments from G-actin is an ATP-dependent process, although not in the conventional sense where it uses the energy released during hydrolysis. Instead, the G-actin subunits only bind with another G-actin subunit if it has first bound an ATP (Figure 9). If the G-actin has bound ADP, then it must first exchange the ADP for ATP before being added to a filament. This process alters the conformation of the subunit to allow for a higher-affinity interaction. A short time later, hydrolysis of the ATP to ADP, with the release of Pi, weakens the affinity but does not directly cause dissolution of the subunit binding. The actin, with intrinsic ATPase activity, brings about the hydrolysis.

Although F-actin primarily exists as a pair of filaments twisted around each other, adding new actin occurs by adding individual G-actin monomers to each filament (Figure 9). Elongating the actin filament occurs when free G-actin bound to ATP associates with the filament. Under physiological conditions, the G-actin associates easier at the plus end of the filament and harder at the minus end.3 However, elongating the filament at either end is possible. Within the cell, the concentrations of G-actin and F-actin continuously fluctuate. When free G-actin levels are high, elongation of actin filaments is favoured, and when the G-actin concentration falls, depolymerization of F-actin predominates. Assembling G-actin into F-actin is regulated by the critical concentration. The critical concentration (CC) is the concentration of either G-actin (actin) or the αβ-tubulin complex (microtubules) at which the end remains in an equilibrium state with no net growth or shrinkage of the fibre.3 Whether the ends grow or shrink entirely depends on the cytosolic concentration of available monomer subunits in the surrounding environment.4 Critical concentration differs from the plus (CC+) and the minus end (CC−); under normal physiological conditions, the critical concentration is lower at the plus end than the minus end.

Examples of how the cytosolic concentration relates to the critical concentration and polymerization are as follows:

- A cytosolic concentration of subunits above both the CC+ and CC− ends results in subunit addition at both ends.

- A cytosolic concentration of subunits below both the CC+ and CC− ends results in subunit removal at both ends.

The simultaneous assembly and disassembly of F-actin is regularly known as “actin treadmilling”. Note that treadmilling is the cytosolic concentration of the monomer subunit between the CC+ and CC− ends, where growth occurs at the plus end and shrinking at the minus end. The cell attempts to maintain a subunit concentration between the dissociation constants at the plus and minus ends of the polymer. Since actin is mostly added onto one end but removed from the other, the net effect is that any given actin monomer in a filament is effectively moving from the plus end to the minus end, even if the overall length of the filament does not change.

Among other functions, accessory proteins can control polymerization and depolymerization, form bundles, arrange networks, and bridge between the different cytoskeletal networks. For actin, the primary polymerization control proteins are profilin, which induces ATP binding to G-actin so it can incorporate into the plus end of the filament3 and thymosin β4, which sequesters G-actin. The Arp2/3 complex nucleates the assembly of new filaments from the sides of F-actin to promote branching. Minus-end capping proteins prevent filament polymerization, and the plus-end capping proteins CapZ, severin, and gelsolin can stabilize the ends of F-actin. Finally, cofilin binds to ADP-actin on the minus end of the filament, which destabilizes it and induces depolymerization.3

Learning Activity: Microfilaments

- Watch the video “Microfilaments (Structure, Assembly, and Function)” (5:29 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018). This video includes microfilament accessory proteins, including Arp2/3, profilin, CapZ, and tropomodulin.

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What proteins comprise microfilaments?

- What is the diameter of a microfilament? How does this compare to the diameters of microtubules and intermediate filaments?

- Where are microfilaments found within the cell? What is their role?

- What is the rate-limiting step in the nucleation of actin filaments?

- How would you draw the shape of an actin monomer? What is each end called? What happens at each end?

- Actin is an ATPase because it hydrolyzes ATP to ADP. Which type of actin can be added to the plus end? What happens to actin at the minus end?

- Why are microfilaments considered dynamic structures?

- What is treadmilling?

- List four ways a cell controls actin polymer (microfilament) length.

- How does Arp2/3 affect the rate of nucleation?

- How does profilin affect actin polymerization?

- What does CapZ do?

- What does tropomodulin do?

Learning Activity: Treadmilling in More Detail

- Watch the video “Cytoskel Actin Treadmilling” (6:09 min) by Joanne Odden (2018).

- Answer the following question based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- Explain what happens to actin monomers as treadmilling occurs.

Cell Crawling

In the early development of animals, there is a significant amount of cellular rearrangement and migration as the roughly spherical blob of cells called the blastula starts to differentiate and form cells and tissues with specialized functions. These cells need to move from their point of birth to their eventual positions in the fully developed animal. Some cells, like neurons, have an additional type of cell motility; they extend long processes (axons) out from the cell body to their target of innervation. In both neurite extension and whole cell motility, the cell needs to first move its attachment points and then the bulk of the cell from one point to another. The cell does this process gradually and uses the cytoskeleton to make the process more efficient. Cell motility includes the following major elements: changing the point of forward adhesion; clearing of internal space by myosin-powered rearrangement of actin filaments; and the subsequent filling of that space with microtubules.

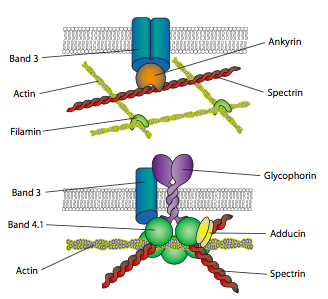

The membrane must be attached to the cytoskeleton for force to be transmitted. In fact, signalling from receptors in the membrane can sometimes directly induce rearrangements or movements of the cytoskeleton via adaptor proteins that connect actin (or other cytoskeletal elements) to transmembrane proteins such as integrin receptors. One of the earliest experimental systems for studies of cytoskeleton-membrane interaction was the erythrocyte (red blood cell) (Figure 10).

The illustrations (Figure 10) show some interactions in an extensive actin filament network with transmembrane proteins. Ankyrin and spectrin are important linkage proteins between the transmembrane proteins and the microfilaments. This idea of building a protein complex around the cytoplasmic side of a transmembrane protein is ubiquitous. Scaffolding (linking) proteins connect the extracellular substrate (via transmembrane protein) to the cytoskeleton and physically connect signalling molecules, thus increasing signal transduction speed and efficiency.

In most cell types, the greatest concentration of actin-based cytoskeletal structures is found in the periphery of the cell rather than towards the centre. This fits well with the tendency for the edges of the cell to be more dynamic, constantly adjusting to sense and reacting to its environment. The polymerization and depolymerization of actin filaments are clearly much faster than intermediate filaments.

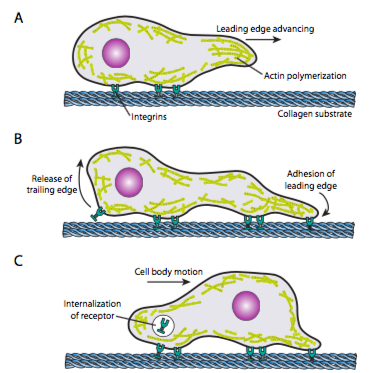

Figure 11 displays the role of actin in cell crawling along a surface. AActin polymerization generates the cell’s leading edge, and the resulting cytoskeletal rearrangements allow the movement of cells along a surface. This can take the form of filopodia or lamellipodia, and often both simultaneously. Filopodia are long and very thin projections with core bundles of parallel microfilaments and high concentrations of cell surface receptors. Their primary purpose is to sense the environment. Lamellipodia often extend between two filopodia and is more of a broad ruffle than a finger. Internally, the actin forms more into meshes than bundles, and the broader edge allows for more adhesions to the substrate. The microfilament network then rearranges again; this time, it opens a space in the cytoplasm that acts as a channel for moving the microtubules toward the front of the cell. This rearrangement puts the transport network in place to help move intracellular bulk material forward. As this occurs, the old adhesions on the tail end of the cell are released. This release can happen through two primary mechanisms: endocytosis of the receptor or deactivation of the receptor by signalling or conformational change. Of course, this oversimplification misrepresents the complexities in coordinating and controlling all these actions to accomplish the directed movement of a cell.

Once a cell receives a signal to move, the initial cytoskeletal response is to polymerize actin, building more microfilaments to incorporate into the leading edge. Depending on the signal (attractive or repulsive), the polymerization may occur on the same or opposite side of the cell from the point of signal-receptor activation. Significantly, the polymerization of new F-actin alone can generate sufficient force to move the membrane forward, even without the involvement of myosin motors (see Unit 3, Topic 5). Force generation models are debated but generally start with incorporating new G-actin into a filament at its tip (the filament-membrane interface). Even if that might technically be enough, in a live cell, myosins help to push and arrange filaments directionally to set up the new leading edge. In addition, some filaments and networks must quickly sever to make new connections, both between filaments and between filaments and other proteins, such as adhesion molecules or microtubules.

Learning Activity: Cell Crawling

- Watch the video “Cytoskel Actin Cell motility” (7:28 min) by Joanne Odden (2018).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- Describe the difference between a lamellipodium and a filopodium.

- Why would a neuron use lamellipodia?

- What are three terms for the movement of a whole eukaryotic cell?

- In what two cell types mentioned in the video is motility important?

- Where is most of the actin found within a crawling cell?

- What part of the cell undergoes protrusion, and how?

- What happens in step 2 of the cell crawling process?

- What happens in step 3 of the cell crawling process?

Learning Activity: Microfilaments and Lymphocyte Motility

- Watch the video “The Role of Actin in Cell Motility.” (5:36 min) by The Science Tutorials Channel (2021).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- List the three phases of actin polymerization.

- What happens during actin nucleation and elongation?

- What happens during the steady state?

- What processes does actin undergo at the leading edge of a motile cell?

- How does actin polymerization differ in filopodia versus lamellipodia?

- What generates the contractile force necessary to pull the cell forward?

Self-Check

- Which cytoskeletal structure is linked with the movements of a macrophage?

- Microfilaments

- Microtubules

- Glycocalyx

- Cilia and flagella

Show/Hide answer.

a. Microfilaments

- Describe how microfilaments and microtubules are involved in the phagocytosis and destruction of a pathogen by a macrophage.

Show/Hide answer.

A macrophage engulfs a pathogen by rearranging its actin microfilaments to bend the plasma membrane around the pathogen. Once the pathogen becomes sealed in an endosome inside the macrophage, the vesicle is walked along microtubules until it combines with a lysosome to digest the pathogen.

Learning Activity: Summary of Intermediate and Microfilaments

- Watch the video “Microfilaments and intermediate filaments” (3:27 min) by Khan Academy (2015).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What type of proteins are microfilaments composed of?

- Microfilaments mediate gross movement in the cell. What is meant by the statement, “microfilaments are dynamic”? What are the two terms for two forms of actin found within cells (see Unit 3, Topic 4 readings)?

- Describe why microfilaments are polarized.

- Provide an example of how microfilaments help with the gross movement of the cell.

- Intermediate filaments are not dynamic, unlike microfilaments and microtubules. What is the role of intermediate filaments in the cell?

Microtubules

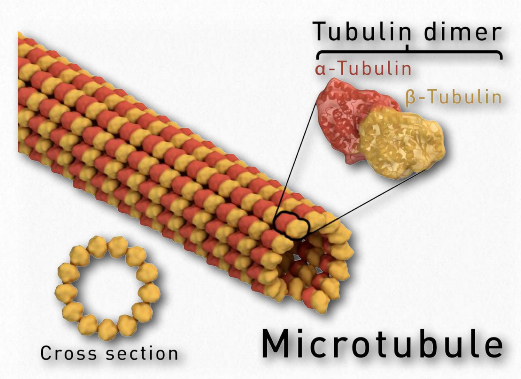

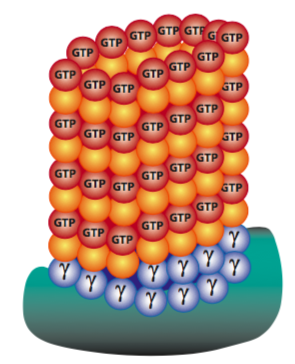

Microtubules are the thickest type of cytoskeletal fibres with a diameter of 25 nm (Figure 1a) and are found throughout the cytoplasm. In a cell, microtubules play an important structural role by helping the cell resist compressive forces. Unlike the twisted-pair microfilaments, the microtubules are usually large 13-stranded (each strand is called a protofilament) hollow tube structures. Globular protein subunits called α-tubulin and β-tubulin form αβ-tubulin dimers that stack to form individual protofilaments (Figure 12).

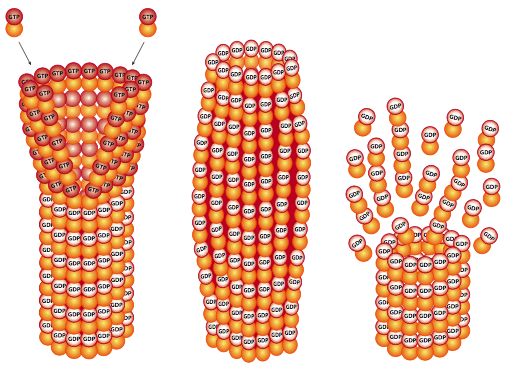

Not only are the α- and β-tubulin used for building the microtubules alternating but they also get added in pairs. Both the α-tubulin and β-tubulin must bind to GTP to associate. GDP-bound αβ-dimers do not get added to a microtubule. Like the situation with ATP and G-actin (see Figure 9), if the tubulin has GDP bound to it, it must first exchange it for a GTP before being polymerized. Although tublin’s affinity for GTP is higher than for GDP, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) usually facilitates this process. As the cell signalling chapter will show in more detail, this type of nucleotide exchange is a common mechanism for activating various biochemical pathways. Microtubule formation can begin, and this is called the nucleation event.

The GTP bound to α-tubulin does not move. On the other hand, GTP bound to β-tubulin may be hydrolyzed to GDP as more GTP-bound tubulin dimers assemble into the protofilament. This changes the attachment between the β-tubulin of one dimer and the α-tubulin of the adjacent dimer it is stacked on because the shape of the subunit changes. Even though it isn’t directly loosening its hold on the neighbouring tubulin, the shape change causes increased stress as that part of the microtubule tries to push outward. If there is nothing to stabilize the microtubule, large portions of it will fall apart. However, as long as new GTP-bound tubulin is being added at a high enough rate to keep a section of low-stress, “stable” conformation microtubule called the GTP cap on top of the older GDP-containing part then it stabilizes the overall microtubule (Figure 13).

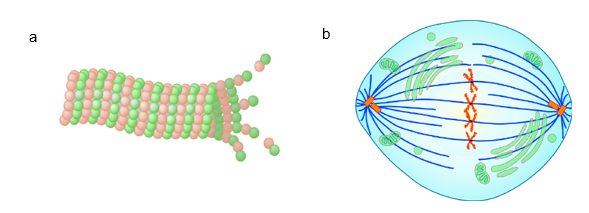

When new tubulin addition slows down, and there is only a very small or nonexistent cap, the microtubule undergoes a catastrophe in which large portions rapidly break apart. Note that this is a very different process than breakdown by depolymerization, which is the gradual loss of only a few subunits at a time from an end of the microtubule. Depolymerization also occurs and, like with actin, is determined partially by the relative concentrations of free tubulin and microtubules. Figure 14a demonstrates the microtubule disassembly, or shortening, as the protofilaments that make up the hollow microtubule “peel” back.

Microtubules have a distinct polarity that is critical for their biological function. Tubulin polymerizes end to end, with the β-subunit of one tubulin dimer contacting the α-subunit of the next dimer. This organization leads to different subunits becoming exposed on the two ends of the filament. The ends are designated the minus (−) and plus (+) ends. Microtubules can elongate at both the plus and minus ends, but elongation is significantly more rapid at the plus end. The ability of the microtubule to assemble and disassemble, thereby changing its length, is termed dynamic instability. Note that dynamic instability is a feature specific to microtubules and actin filaments (as described Figure 13) and is integral to some cellular functions. One example of this is chromosomes moving to opposite poles of a dividing cell during mitosis, which depends on polymerization and depolymerization of microtubules, called spindle fibres, that originate from the microtubule organizing centre (MTOC) (Figure 14b).

Microtubule Organizing Centres — Centrosomes

Microtubules, like microfilaments, are dynamic structures, changing in length and interactions to react to intra- and extracellular changes. However, the general placement of microtubules within the cell significantly differs from microfilaments, although they have some overlap and interaction. Microfilaments do not have any global organization with respect to their polarity. They start and end in many areas of the cell. On the other hand, almost all microtubules have their minus end at the MTOC in the perinuclear region and radiate outward from that centre. Since the microtubules radiate outward from the MTOC, it is not surprising that they are concentrated more centrally in the cell than the microfilaments, which, as mentioned above, are more abundant around the cell’s periphery.

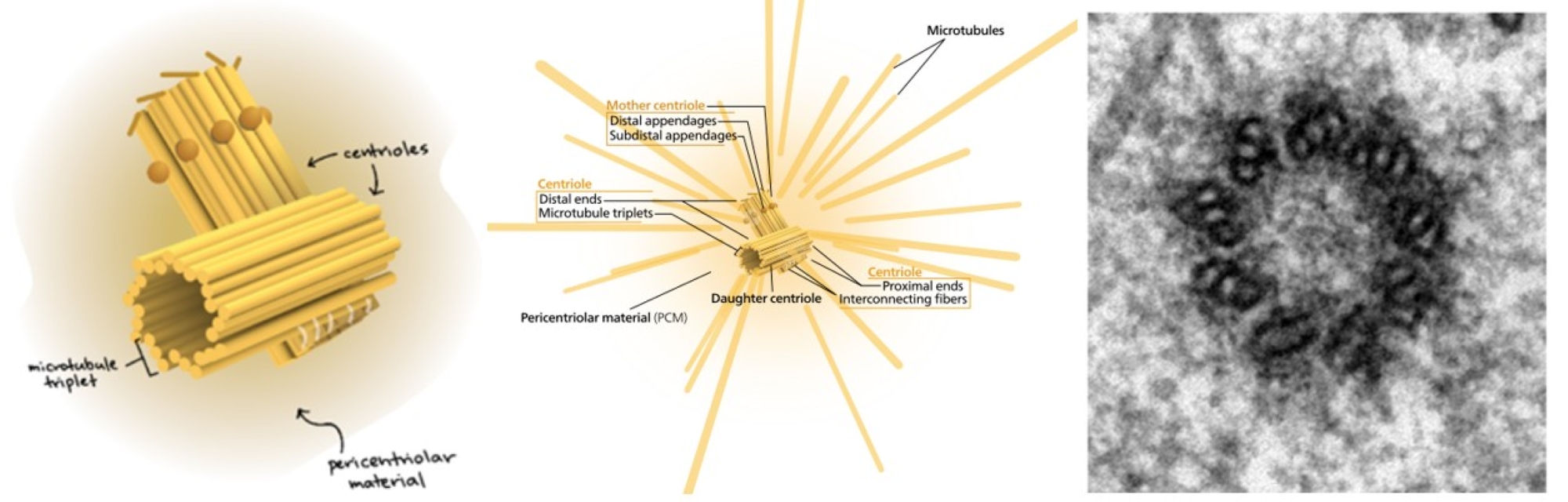

In some cell types (primarily animal), the MTOC contains a structure known as the centrosome (Figure 15, Left). The centrosome consists of a centriole, two short barrel-shaped microtubule-based structures positioned perpendicular to each other, and a poorly defined concentration of pericentriolar material (PCM, sometimes also called pericentriolar matrix). The PCM is a highly structured5, dense mass of protein which makes up the part of the animal centrosome that surrounds the two centrioles. The PCM contains proteins responsible for microtubule nucleation and anchoring,5,6 including γ-tubulin, pericentrin, and ninein. A centriole is a cylinder of nine triplets of microtubules held together by supporting proteins that all connect to form a cylinder, and each also connects by radial spokes to a central axis. The electron micrograph in Figure 15, Right shows a cross-section of a centriole in which each fibril is a fused triplet of microtubules.

In each triplet, only one is a complete microtubule (designated the A tubule), while the B and C tubules do not form complete tubes, as they share a wall with the A and B tubules, respectively. Interestingly, the centrioles do not appear connected to the cellular microtubule network. However, whether there is a defined centrosome or not, the MTOC region is the point of origin for all microtubule arrays because the MTOC contains a high γ-tubulin concentration. Why is this important? With all cytoskeletal elements, though most pronounced with microtubules, the nucleation rate (starting a microtubule) is significantly slower than the rate of elongating an existing structure. Since it is the same biochemical interaction, the assumption is that the difficulty lies in getting the initial ring of dimers into position. The γ-tubulin facilitates this process by forming a γ-tubulin ring complex that serves as a template for the nucleation of microtubules (Figure 16). This is true in animal and fungal cells, which have a single defined MTOC; meanwhile, plants have multiple dispersed sites of microtubule nucleation.

Learning Activity: Microtubule (MT) Structure and Formation

- Watch the video “Microtubules (Structure and Function)” (7:27 min) by Cell Bio Clips (2018).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- List three functions of microtubules.

- What type of protein monomers make up microtubules?

- What is a dimer? What dimers comprise microtubules? What shape do they make? What is the diameter of a microtubule?

- What dictates microtubule polarity, such as the plus and minus ends?

- What is a microtubule seed? How does it relate to nucleation?

- How do microtubules grow in length?

- How many protofilaments surround the hollow core?

- What is the rate-limiting step of microtubule formation? How does the cell accelerate this step?

- What is a microtubule organizing centre (MTOC)?

- Provide two examples of MTOCs in cells. Describe the general arrangement of microtubules in each.

- What is the 9+2 arrangement of cilia and flagella?

- Which end of microtubules grows fastest out of MTOCs? Why?

- What is one reason that microtubule assembly must be a dynamic process during cell division?

- How is GTP involved in microtubule stability?

Learning Activity: Microtubules, Dynamic Instability, and the Effects of GTP/GDP

- Watch the video “Microtubules” (3:24 min) by VideosMolecular (2013).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What is dynamic instability?

- What is catastrophe?

- Describe what happens to tubulin when GDP is exchanged for GTP.

Learning Activity: Microtubules — Do I Shrink or Do I Grow?

- Watch the video “Cytoskel MTs GTP cap” (8:02 min) by Joanne Odden (2018).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 4 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What is a GTP cap? Where is it found?

- Where is GDP-bound tubulin found in a microtubule?

- How does a microtubule get a GTP cap?

- Why is the plus end more stable than the minus end of a microtubule?

- What happens when the GTP cap is lost?

- What is rescue?

- Watch the video “Microtubule Dynamics in vivo” (1:19 min) by Ryan Abbott (2017).

Explain the difference in visualizing microtubules with a fluorescent protein found only in the Cap (EB1) and another where tubulin is fluorescently labelled along the length of each microtubule. - Watch the animation “MicrotubuleDynamicInstability” by Nogales and University of California, Berkeley (2014). Tubulin dimers bound to GTP (red) bind to the growing end of a microtubule and subsequently hydrolyze GTP into GDP (blue).

Describe how this animation depicts microtubule catastrophe.

Key Concepts and Summary

If you removed all organelles from a cell, would the plasma membrane and the cytoplasm be the only components left? No. Within the cytoplasm, there would still be ions and organic molecules, plus a network of protein fibres that help maintain the shape of the cell, secure some organelles in specific positions, allow cytoplasm and vesicles to move within the cell, and enable cells within multicellular organisms to move. Collectively, this network of protein fibres is known as the cytoskeleton.

The cytoskeleton includes three types of fibres: microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules (Figure 17). The cytoskeletal elements, from narrowest to widest, are the microfilaments (actin filaments), intermediate filaments, and microtubules with the following characteristics:

- Intermediate filaments are structural components that bear tension and anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place.

- Biologists often associate microfilaments with myosin. They provide rigidity and shape to the cell and facilitate cellular movements (such as cell crawling) within the cell.

- Microtubules help the cell resist compression, serve as tracks for motor proteins that move vesicles through the cell, and pull replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell. They are also the structural elements of centrioles, flagella, and cilia.

Intermediate filament structure and function

This cytoskeletal component consists of a diverse group of fibrous proteins that form coiled-coil dimers. Dimers join to make tetramers, which are staggered in an antiparallel fashion and wrapped together to form larger bundles (protofibrils) of eight tetramers with 8–12 nm diameters. Intermediate filaments are not dynamic like microtubules and microfilaments and do not break down easily. Intermediate filament functions include the following:

- Tension bearing to provide tensile strength

- Supporting cell-cell junctions through keratin in desmosomes of epithelial cells

- Anchoring cells to extracellular structures

- Maintaining the shape of the nuclear envelope through lamins

Microfilament structure and function

Microfilaments are composed of two strands of F-actin twisted around each other, reaching a diameter of 7 nm. These filaments are polarized like microtubules and result from the polymerization of ATP-bound G-actin monomers at the plus end. Actin-binding proteins regulate microfilament growth and branching. Microfilament functions include the following:

- Resisting tension to maintain cell shape

- Mediating changes in cell shape

- Cell motility/crawling by lamellipodia/filopodia

- Cell division by actomyosin cleavage furrow formation (Unit 3, Topic 5)

- Myosin-mediated muscle contraction (Unit 3, Topic 5)

Microtubule structure and function

Microtubules grow out of microtubule organizing centres that act as nucleation sites containing γ-tubulin, which acts as a seed for polymerization. Microtubules are hollow structures with a 25-nm diameter composed of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that polymerize into 13 linear protofilaments with plus and minus ends. Microtubule growth occurs more readily at the plus end, which has a lower critical concentration for heterodimer addition than the minus end. Dynamic instability refers to the ability of microtubules to assemble and disassemble. Catastrophe occurs when β-tubulin hydrolyzes GTP at the plus end, resulting in a loss of the cap and replenishing the GTP cap in recovery. Microtubule functions include the following:

- Resisting compression to maintain cell shape

- Cell motility

- Chromosome separation during cell division

- Tracks for vesicle and organelle movements

Key Terms

actin

a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils

actin-binding proteins

proteins that bind to filamentous actin to regulate its polymerization or branching

alpha (α)-tubulin

a tubulin monomer that binds to β-tubulin to form a heterodimer that polymerizes to form the protofilaments of microtubules

anterograde transport

movement of vesicles toward the plasma membrane

Arp2/3 complex

actin-binding proteins that aid in branching from the sides of filamentous actin by providing a nucleation point

beta (β)-tubulin

a tubulin monomer that binds to α-tubulin to form a heterodimer that polymerizes to form the protofilaments of microtubules

capping protein

blocks the addition or loss of subunits by binding to the plus ends of F-actin filaments

centriole

a structure consisting of nine sets of triplet microtubules embedded in the centrosome of animal cells

centrosome

a complex that serves as the primary microtubule organizing centre of animal cells; composed of two centrioles arranged at right angles to each other

cytoskeleton

protein fibre network that collectively maintains the cell’s shape, secures some organelles in specific positions, allows cytoplasm and vesicles to move within the cell, and enables unicellular organisms to move independently

F-actin

filamentous actin is part of a linear polymer microfilament

filopodium (plural filopodia)

slender cytoplasmic projections that extend beyond the leading edge of lamellipodia in migrating cells

G-actin

globular actin is a free monomer form of actin that can polymerize into filamentous actin

integrin

transmembrane receptors that connect cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion

intermediate filament

cytoskeletal component, comprised of several fibrous protein intertwined strands, that bears tension, supports cell-cell junctions, and anchors cells to extracellular structures

lamellipodium (plural lamellipodia)

a thin sheet containing cytoskeletal protein actin projections on the leading edge of the cell

microfilament

the cytoskeleton system’s narrowest element; it provides rigidity and shape to the cell and enables cellular movements

microtubule

the cytoskeleton system’s widest element; it helps the cell resist compression, provides a track along which vesicles move through the cell, pulls replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell, and is the structural element of centrioles, flagella, and cilia

myosin

a superfamily of ATP-dependent motor proteins responsible for actin-based motility in the cytoplasm and in muscle contraction

nucleation

the event that initiates de novo formation of microtubules often referred to as the seed of γ-tubulin that forms a scaffold for the addition of α/β-tubulin dimers

pericentriolar material

a region surrounding centrioles containing proteins responsible for microtubule nucleation and anchoring such as γ-tubulin

treadmilling

occurs when one end of a filament/microtubule grows in length while the other end shrinks, resulting in a section of filament/microtubule seemingly “moving” across a stratum or the cytosol

tubulin

a member of a superfamily of globular proteins that polymerize into microtubules

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 1-1 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 1-2 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: (Left) Figure 1-3 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. (Right) Desmosome cell junction en by Mariana Ruiz [LadyofHats] (2007), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 4: Figure 1-4 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Structure and function of the nuclear lamina by Coutinho et al. (2009), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

- Figure 6: Figure 1-5 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Figure 1-10 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Figure 12.3.3 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 9: Thin filament formation by Mikael Häggström (2008), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 10: Figure 12.8.15 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 11: Figure 1-11 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: Figure 1-6 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 12.4.4 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 14: Figure 1-7 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 15: (Left) Centriole-en by Kelvinsong (2013), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 3.0 license. (Middle) Figure 1 Diagram of a centrosome. “Centrosome”, by Kelvinsong (Kelvinsong 2013/Wikimedia Commons) CC BY 3.0. (Right) Figure 12.5.5 by L. Howard and M. Marin-Padilla 1985, from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022), is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 16: Figure 12.5.6 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 17: Figure 4.5.1 from OpenStax General Biology 1e (OpenStax 2022) is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

6 Andersen JS, Wilkinson CJ, Mayor T, Mortensen P, Nigg EA, Mann M. 2003. Proteomic characterization of the human centrosome by protein correlation profiling. Nature. 426:570-574. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature02166. doi:10.1038/nature02166.

1 Capell BC, Collins FS. 2006. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet. 7:940-952. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg1906. doi:10.1038/nrg1906.

Cell Bio Clips. Microfilaments (structure, assembly, and function) [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Sep 21, 5:29 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qm5TCc897FM.

Cell Bio Clips. Intermediate filaments (structure and function) [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Oct 3, 3:37 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m308ZcpDbpE.

Cell Bio Clips. Microtubules (structure and function) [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Oct 18, 7:27 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpEKOH4LBAc.

Coutinho, HDM, Falcão-Silva VS, Gonçalves, GF, Batista da Nóbrega R. 2009. Molecular ageing in progeroid syndromes: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome as a model. Immun Ageing. 6(4). https://immunityageing.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1742-4933-6-4#citeas. doi:10.1186/1742-4933-6-4.

2 Coutinho, HDM, Falcão-Silva VS, Gonçalves, GF, Batista da Nóbrega R. 2009. Structure and function of the nuclear lamina [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2010 Jan 3; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8896772.

Häggström M. 2008. Thin filament formation [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2008 Jan 21; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thin_filament_formation.svg.

Joanne Odden. Cytoskel actin treadmilling [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Mar 21, 6:09 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5q0-jnKHqM.

Joanne Odden. Cytoskel actin cell motility [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Mar 22, 7:28 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEltmbL-eKE.

Joanne Odden. Cytoskel MTs GTP cap [Video]. YouTube. 2018 Mar 29, 8:02 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oc39Y__bLyY.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 10: vesicles in the endomembrane system. Figures 1-1 to 1-7, 1-10, 1-11. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/301523e1-6d5d-488f-8dce-e73b46200340.

Kelvinsong. 2013. Centriole-en [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2013 Aug 14; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Centriole-en.svg.

Khan Academy. Microfilaments and intermediate filaments [Video]. Khan Academy. 2015 Jan 28, 3.26 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.khanacademy.org/test-prep/mcat/cells/cytoskeleton/v/microfilaments-and-intermediate-filaments-2.

Khan Academy. The cytoskeleton. Khan Academy. 2015 Jul 27, 6:52 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 2]. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/structure-of-a-cell/tour-of-organelles/v/cytoskeletons.

5 Lawo S, Hasegan M, Gupta GD, Pelletier L. 2012. Subdiffraction imaging of centrosomes reveals higher-order organizational features of pericentriolar material. Nat Cell Biol. 14:1148-1158. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncb2591. doi:10.1038/ncb2591.

Nogales E, University of California, Berkeley. 2014. MicrotubuleDynamicInstability [animation]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2014 Dec 8; accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MicrotubuleDynamicInstability.ogv.

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax).

OpenStax. 2022. General biology 1e (OpenStax). Microbiology. Houston (TX): OpenStax; [accessed 2024 Jan 24]. Figure 4.5.1. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_1e_(OpenStax)/2%3A_The_Cell/04%3A_Cell_Structure/4.5%3A_The_Cytoskeleton.

3 Remedios CGD. Chhabra D, Kekic M. Dedova IV, Tsubakihara M, Berry DA, Nosworthy NJ. 2003. Actin binding proteins: regulation of cytoskeletal microfilaments. Physiol Rev. 83(2):433-473. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.00026.2002. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2002.

Ruiz M [LadyofHats]. 2007. Desmosome cell junction en [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2009 Mar 10; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Desmosome_cell_junction_en.svg.

Ryan Abbott. 17 1 intermediate filaments [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Apr 26, 2:28 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Zx33K-8Yes.

Ryan Abbott. Microtubule dynamics in vivo [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Apr 26, 1:19 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHUXRyCY7LM.

4 Schaus TE, Taylor EW, Borisy GG. 2007. Self-organization of actin filament orientation in the dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling model. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 104(17):7086-7901. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0701943104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701943104.

The Science Tutorials Channel. The role of actin in cell motility [Video]. YouTube. 2021 Feb 23, 5:13 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n9q7I-mlnm8.

VideosMolecular. Microtubules [Video]. 2013 Jun 19, 3:24 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 25]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGmz4xVP50M.

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Figures 12.3.3, 12.4.4, 12.5.5, 12.5.6, 12.8.15. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

protein fibre network that collectively maintains the cell’s shape, secures some organelles in specific positions, allows cytoplasm and vesicles to move within the cell, and enables unicellular organisms to move independently

the cytoskeleton system’s narrowest element; it provides rigidity and shape to the cell and enables cellular movements

a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils

cytoskeletal component, comprised of several fibrous protein intertwined strands, that bears tension, supports cell-cell junctions, and anchors cells to extracellular structures

the cytoskeleton system’s widest element; it helps the cell resist compression, provides a track along which vesicles move through the cell, pulls replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell, and is the structural element of centrioles, flagella, and cilia

globular actin is a free monomer form of actin that can polymerize into filamentous actin

filamentous actin is part of a linear polymer microfilament

a member of a superfamily of globular proteins that polymerize into microtubules

occurs when one end of a filament/microtubule grows in length while the other end shrinks, resulting in a section of filament/microtubule seemingly “moving” across a stratum or the cytosol

actin-binding proteins that aid in branching from the sides of filamentous actin by providing a nucleation point

blocks the addition or loss of subunits by binding to the plus ends of F-actin filaments

a superfamily of ATP-dependent motor proteins responsible for actin-based motility in the cytoplasm and in muscle contraction

transmembrane receptors that connect cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion

slender cytoplasmic projections that extend beyond the leading edge of lamellipodia in migrating cells

a thin sheet containing cytoskeletal protein actin projections on the leading edge of the cell

a tubulin monomer that binds to β-tubulin to form a heterodimer that polymerizes to form the protofilaments of microtubules

a tubulin monomer that binds to α-tubulin to form a heterodimer that polymerizes to form the protofilaments of microtubules

the event that initiates de novo formation of microtubules often referred to as the seed of γ-tubulin that forms a scaffold for the addition of α/β-tubulin dimers

a complex that serves as the primary microtubule organizing centre of animal cells; composed of two centrioles arranged at right angles to each other

a structure consisting of nine sets of triplet microtubules embedded in the centrosome of animal cells

a region surrounding centrioles containing proteins responsible for microtubule nucleation and anchoring such as γ-tubulin

proteins that bind to filamentous actin to regulate its polymerization or branching