3.5 Transport Using the Cytoskeleton

Introduction

While it can be helpful to think of cytoskeletal structures as analogous to an animal skeleton, perhaps a better way to remember the relative placement of microtubules and microfilaments is by their function in transporting intracellular cargo from one part of the cell to another. By that analogy, microtubules make up a railroad track system, while microfilaments are more like streets. By the same analogy, microtubule and microfilament networks are connected at specific points so that when cargo reaches its general destination by microtubule (rail), it can be taken to its particular address by microfilaments. To extend this analogy further, if there are “railroad tracks,” there must be an engine that can both move on the tracks and pull or push cargo along. In this case, the engines are molecular motors, called motor proteins, that can move along the tracks in a specific direction.

Motor proteins use energy in the form of ATP to “walk” along specific cytoskeletal tracks; therefore, they are classified as proteins that convert chemical energy into mechanical work by ATP hydrolysis. They are essential for moving vesicles and other cargoes within cells, as well as for moving the cytoskeleton, muscle fibres, cilia and flagella. Motor proteins utilizing the cytoskeleton for movement fall into two categories based on their substrate: microfilaments or microtubules. Unit 3, Topic 5 will discuss the following three types of motor proteins and their associations with the cytoskeleton:

- Kinesin and its association with tubulin microtubules

- Dynein and its association with tubulin microtubules

- Myosin and its association with actin filaments

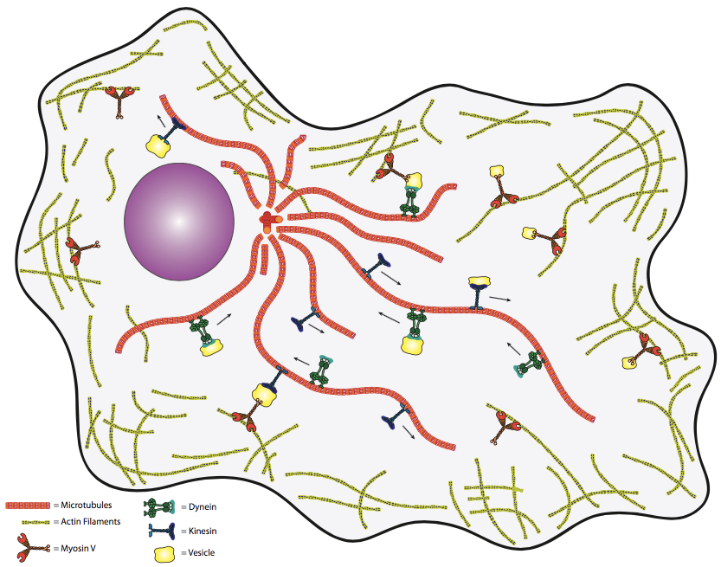

These motor proteins and the cytoskeleton create a comprehensive network within the cell for moving vesicles from one organelle to another or from one organelle to the cell surface and vice versa (Figure 1). One might question the biological need for such a transport system. Again, in the human transport analogy, transport via simple diffusion is akin to people carrying packages randomly about the cell. That is to say, the deliveries will eventually be made, but do not count on this method for time-critical materials. Thus, a directed, high-speed system is needed to keep cells (particularly larger, eukaryotic cells) alive.

Unit 3, Topic 5 Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 3, Topic 5, you will be able to:

- Use proper terminology to describe and draw the structures of kinesin, dynein and myosin.

- Use proper terminology to compare how motor protein structure relates to the functions of directional microfilament and/or microtubule movement and their mechanochemical cycles.

- Compare and contrast the structure of centrioles, cilia, and flagella.

| Unit 3, Topic 5—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min.) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Unit 3, Topic 5 of TRU Cell and Molecular Biology. | 60 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Drew Berry—Animations of unseeable biology. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: What is kinesin? Ron Vale explains. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microtubules—Kinesin structure and function. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Microtubules—Visualizing kinesin activity using fluorescence microscopy. | 4 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Motility in a test tube. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Molecular motor struts like drunken sailor. | 4 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cytoplasmic dynein—structure and function. | 15 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary—Cytoskeletal molecular motor proteins I. | 45 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary—Cytoskeletal molecular motor proteins II. | 50 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Axoneme structure of cilia and flagella. | 4 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Origin of cilia and flagella. | 10 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How do cilia and flagella move? | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cilia—Nature’s exquisite nanomachines. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Myosin structure and function. | 12 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Formation of the actomyosin ring. | 5 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Summary of cytoskeleton structure and function. | 12 |

Learning Activity: Drew Berry — Animations of Unseeable Biology

Complete this activity before reading further.

- Watch the video “Animations of unseeable biology | Drew Berry | TED” (9:08 min) by TED (2012) to get inspired by the amazing molecular structures and by humans’ ability to visualize and recreate their stories within cells. Make your own notes.

Movement Along Microtubules

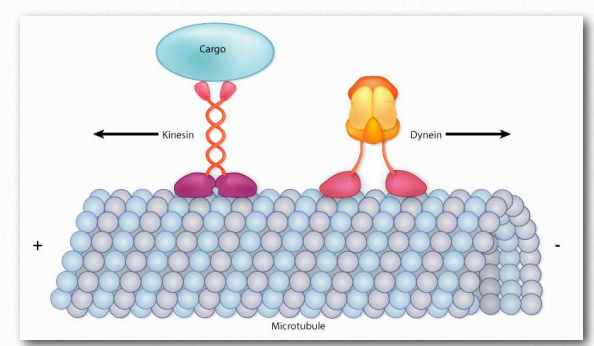

There are two basic types of microtubule motors: plus-end motors and minus-end motors, depending on the direction in which they “walk” along the microtubule cables within the cell. As previously noted, one function of microtubules is to move cellular components from one part of the cell to another (see Unit 3, Topic 4). These cellular components are called “cargo” and are often stored within a vesicle for retrograde or anterograde transport (see Unit 3, Topic 3). To somewhat generalize, kinesins use energy supplied by ATP hydrolysis to drive toward the plus end, the cell periphery, while dyneins go toward the minus end, the MTOC (Figure 2).

The Kinesin Superfamily

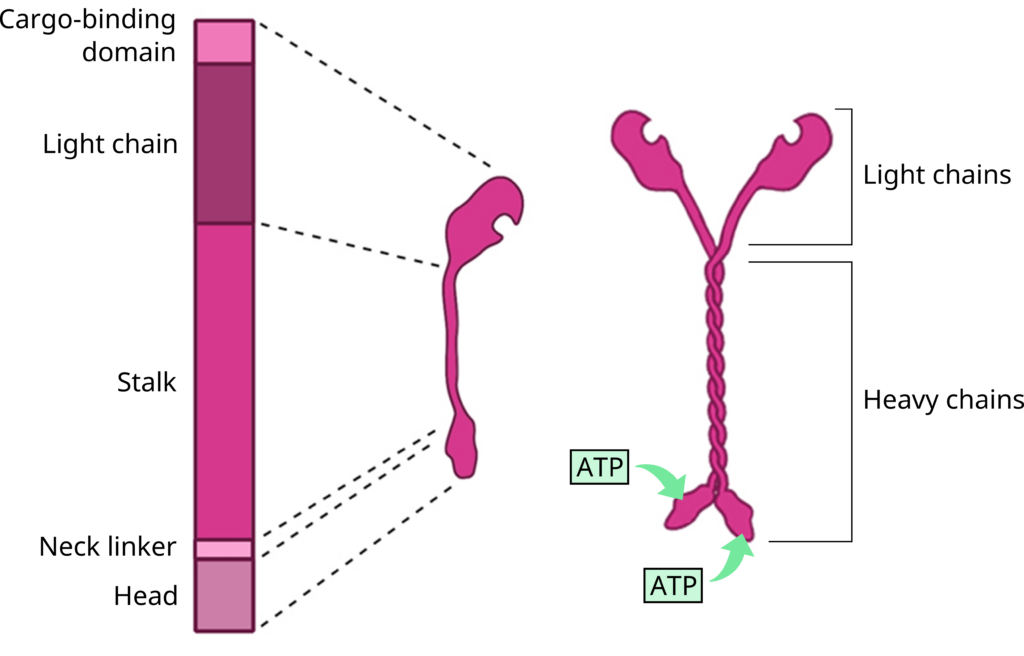

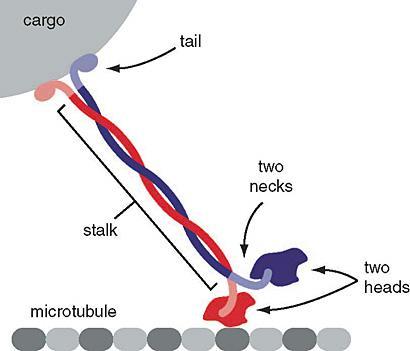

The kinesin superfamily of proteins represents a large class of motor proteins that carry cargo along microtubules. The kinesin family comprises at least 45 isoforms in humans alone. In their inactive state, the kinesins are monomers, each possessing an N-terminal head (motor region), neck linker and globular tail domain (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Between the neck linker and tail domain, a long α-helical coiled-coil region serves as a dimerization site that twists with the corresponding site of another monomer to produce the active kinesin dimer.

The amino-terminal “head” regions are the motor domains in the heavy chains of kinesin. They are the catalytic energy-releasing regions connected to a hinge or neck that bind to microtubules and ATP. They act as a lever, allowing the molecule to flex or “step.” The kinesin head catalyzes ATP hydrolysis, releasing energy to change its conformation relative to the neck and tail of the molecule. This energy allows the kinesin to temporarily release its grip on the microtubule, swivel its “hips” around to plant itself a “step” away and rebind to the microtubule. A cargo-carrying tail in the light chain can also bind to other cellular components likeorganelles or vesicles (Figure 3 and Figure 4).1

Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore

Figure 4: Kinesin. The motor protein kinesin (red and blue) has the head portion of the protein “walking” along the microtubule while the “tails” are bound to vesicles carrying cargo proteins. Left: (Katzman et al. 2020/Fundamentals of Cell Biology) CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Link to: https://giphy.com/gifs/protein-kinesin-Vg711CGH7x55K for an animation.

Learning Activity: What is Kinesin? Ron Vale Explains.

- Watch the video “What is Kinesin? Ron Vale Explains” (3:39 min) by UC San Francisco (UCSF) (2018). Ron Vale explains the inner workings of the motor protein kinesin (“kin-EE-sin”) that transports vital components within cells and separates chromosomes during cell division. He discovered kinesin at Woods Hole, MA and continued his kinesin research at UCSF. Make your own preliminary notes.

The Mechanochemical Cycle of Kinesin

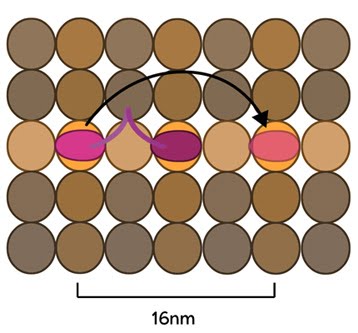

Conventional kinesins move along microtubule filaments in a manner that resembles human walking. This movement has been described as an asymmetric ‘hand-over-hand’ mechanism where one head domain steps forward ~16.2 nm while the other remains stationary on β-tubulin monomers (Figure 5).

Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore

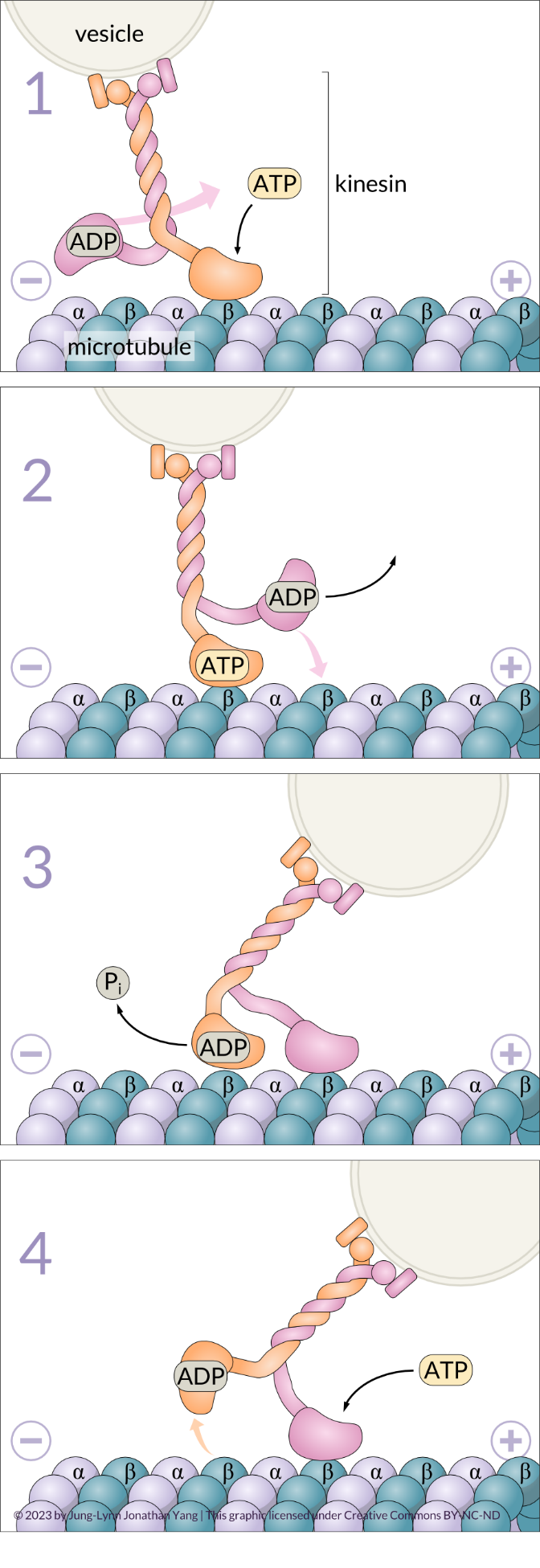

The kinesin-1 molecule exhibits processivity, meaning it can move long distances along a microtubule before detaching from it.2,3 The mechanochemical cycle of kinesin-1 is well understood and involves the cooperation of both motor heads. These motor heads ‘walk head-over-head’ from β-tubulin monomer to β-tubulin monomer; this occurs in an alternating cycle of exchanging ADP for ATP, the hydrolysis of ATP and the release of inorganic phosphate (Pi). At the beginning of the cycle, the leading head (orange strand in Figure 6-1) receives a new ATP molecule, which causes a conformational change that strengthens itsattachment to a β-tubulin monomer. The binding of ATP also causes the neck linker to move and dock into the head, which pulls the lagging ADP-bound head forward to the next available β-tubulin monomer on the plus end (16 nm ahead of its previous site) (pink strand in Figure 6-2). The ADP-bound lagging head now becomes the new leading head. It releases its ADP (pink strand in Figure 6-3) once bound to the β-tubulin monomer and can now accept a new ATP molecule (pink strand in Figure 6-4) to strengthen its attachment to the microtubule. Meanwhile, the new lagging head uses its ATPase activity to hydrolyze its bound ATP (orange strand in Figure 6-3); it releases the resultant inorganic phosphate, and the linker changes conformation to become undocked from the head. The ADP-bound lagging head is now loosely attached to the microtubule and ready to take another ‘step’ or ‘power stroke.’ This way, a mechanical process (physical movement) becomes coupled to chemical processes (ADP/ATP exchange and ATP hydrolysis).

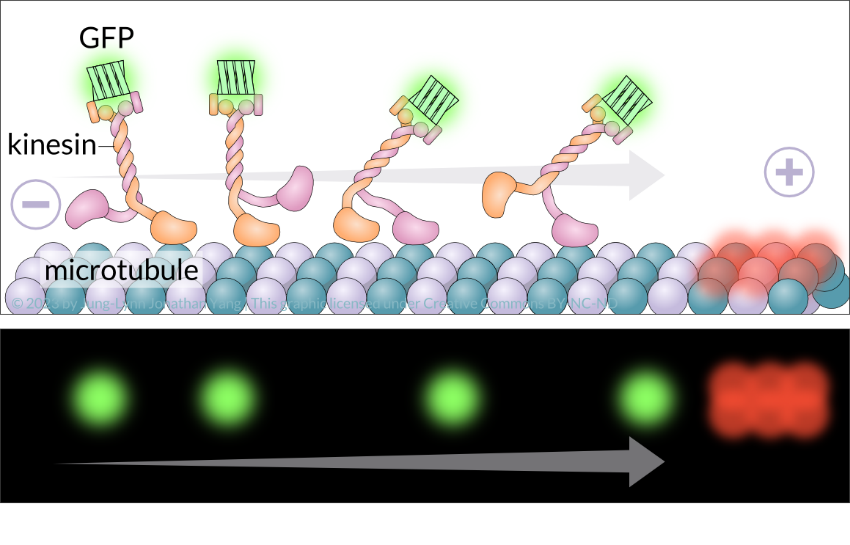

How can motor protein movement be visualized? Researchers can use multiple approaches and fluorescence microscopy to visualize the direction and how fast motor proteins travel on microtubules in real-time. In an in vitro motility assay (Figure 7), kinesin molecules combine with green fluorescent protein and red fluorescent tubulin monomers label microtubules labelled on the plus end. They can also attach a fluorescent bead onto a motor protein of interest and watch it move in cell culture. Alternatively, a fluorescent dye can directly attach to the motor protein. Lastly, the motor protein can be immobilized (stuck) to a fluorescently labelled microtubule and its movements monitored.

Learning Activity: Microtubules — Kinesin Structure and Function

- Watch the following videos:

- “033-Kinesin Structure & Function” (7:06 min) by Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2014).

- “Kinesin Walking Narrated Version for Garland” (2:00 min) by Graham Johnson (2011) to understand the role of ATP in kinesin motor activity. Mike Morales and Peter Walter created a narration for Garland publishers Molecular Biology of the Cell, Alberts et al. (2002).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the videos.

- To which tubulin monomer does the kinesin head bind on the microtubule?

- ATP-bound kinesin binds strongly to the microtubule. What is the consequence?

- What happens to the ATP-bound trailing (or lagging) head now?

- What role does kinesin play in a neuron?

- Draw this whole process and label the parts of the kinesin molecule and the polarity of the microtubule ends.

Learning Activity: Microtubules — Visualizing Kinesin Activity Using Fluorescence Microscopy

- Watch the video “Kinesin walking on Microtubules” (28 s) by Cytopirate Labs (2017).

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in the video and integrate this information with what you have learned in Unit 1, Topic 3:

- What is the name of the assay used in this video?

- What two elements were labelled and how?

Learning Activity: Motility in a Test Tube

- Go to The Explorer’s Guide to Biology and read “Motility in a Test Tube” by Ron Vale (2019) to understand how a motor protein can be isolated and studied in vitro.

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in the video and integrate this information with what you have learned in Unit 1, Topic 3:

- What organism was used to study axonal transport?

- When were these studies initiated?

- Click on “Go to Key Experiment” at the bottom right of the screen in the site above. Read through the primary researcher’s (Ron Vale) recounting of his PhD work using “in vitro reconstitution” in the lab.

- Answer the following questions:

- Watch Video 1 “Transport of Organelles in an Intact Axon” (00:21 min). Attempt the “Explorer’s Question”.

- Watch Video 2 “Using Squid to Study Axonal Transport” (2:00 min). Make your own notes on why squid is a good experimental system for studying this process.

- Watch Video 3 “Organelle Transport Along Filaments in the Dissociated Axoplasm From the Squid Giant Axon” (0:50 min). What type of microscopy did the researchers use to watch the movement of organelles inside squid giant axons? Attempt the “Explorer’s Question”.

- Review cytoskeletal dynamics by watching Video 4 “The Cytoskeleton” (2:00 min). Make your own notes.

- Watch Video 5 “Preparing Samples for the In Vitro Motility Experiment” (9:12 min).

Where did the researchers get the tubulin to reconstitute microtubules? Where did they get the organelles and soluble protein fractions? How did they separate the organelles from the soluble proteins from the axoplasm? Why should a good biochemist keep all of their fractions? - Review Video 6 “Organelles of the Cell” (5:15 min). Make your own notes.

- Watch Video 7 “Reconstituting Motility In Vitro.” (4:38 min). What unexpected results did he encounter in his first experimental attempt?

- What was the result of Ron Vale’s second experimental attempt? What did he do differently?

- Why are control experiments the foundation of experimental cell biology? Why did Ron Vale need one in his reconstitution experiments? List the variables in Ron’s experiments. Attempt the “Explorer’s Question” on positive and negative controls.

- In Ron’s third experimental attempt, how did Ron ensure that the objects moving along microtubules were the membrane organelles?

- Watch Video 8 “Movement of Microtubules Along a Glass Surface” (00:17 min), and read Dig Deeper 3 to understand the results of Ron’s third experimental attempt. What was the clue that the microtubules were being moved?

- Describe how the experiment in Figure 13 tests the hypothesis that stationary motor proteins propel microtubules on a glass slide. What was the negative control? What else did the researchers stick the soluble fraction to?

- Describe the term ‘assay.’

- What did Ron Vale do next with his in vitro reconstitution assays?

- Watch Video 10 “What Happened Next After the In Vitro Motility Assays” (2:43 min). What was special about the in vitro motility assays?

- What does Ron Vale’s story of his in vitro motility experiments suggest about the scientific method?

The Dynein Superfamily

Dyneins are a family of cytoskeletal motor proteins that are the largest and fastest of those known to move along microtubules in cells. Like kinesins, they move processively along microtubules by converting the chemical energy stored in ATP to mechanical work. The dynein family has two major branches. Axonemal dyneins facilitate the beating of cilia and flagella by rapid and efficient sliding movements of microtubules. Another branch is cytoplasmic dyneins, which facilitate the transport of intracellular cargo. All these functions rely on the dynein’s ability to move towards the minus end of the microtubules, known as retrograde transport (see Unit 3, Topic 3); thus, they are called “minus-end directed motors.” Compared to 15 types of axonemal dynein, only two cytoplasmic forms are known.

Many different processes use cytoplasmic dynein proteins. They are involved in organelle movement; for example, they help position organelles in the cell for transporting cargo, such as moving vesicles made by the endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, and lysosomes. They also help position the Golgi apparatus as well as the centrosome and nucleus during cell migration and construct the microtubule spindle during mitosis and meiosis.

Learning Activity: Molecular Motor Struts Like Drunken Sailor

- Watch the animation “Molecular Motor Struts Like Drunken Sailor” (30 s) by Harvard Medical School (2012). Try to catch the various conformational changes happening as dynein “walks” along the microtubule.

- Answer the following questions:

- What conformational changes can you see in each of the two dynein molecules?

- What other motions can you observe in this animation?

Come back and review this animation after you have learned more details from the Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and subsequent videos.

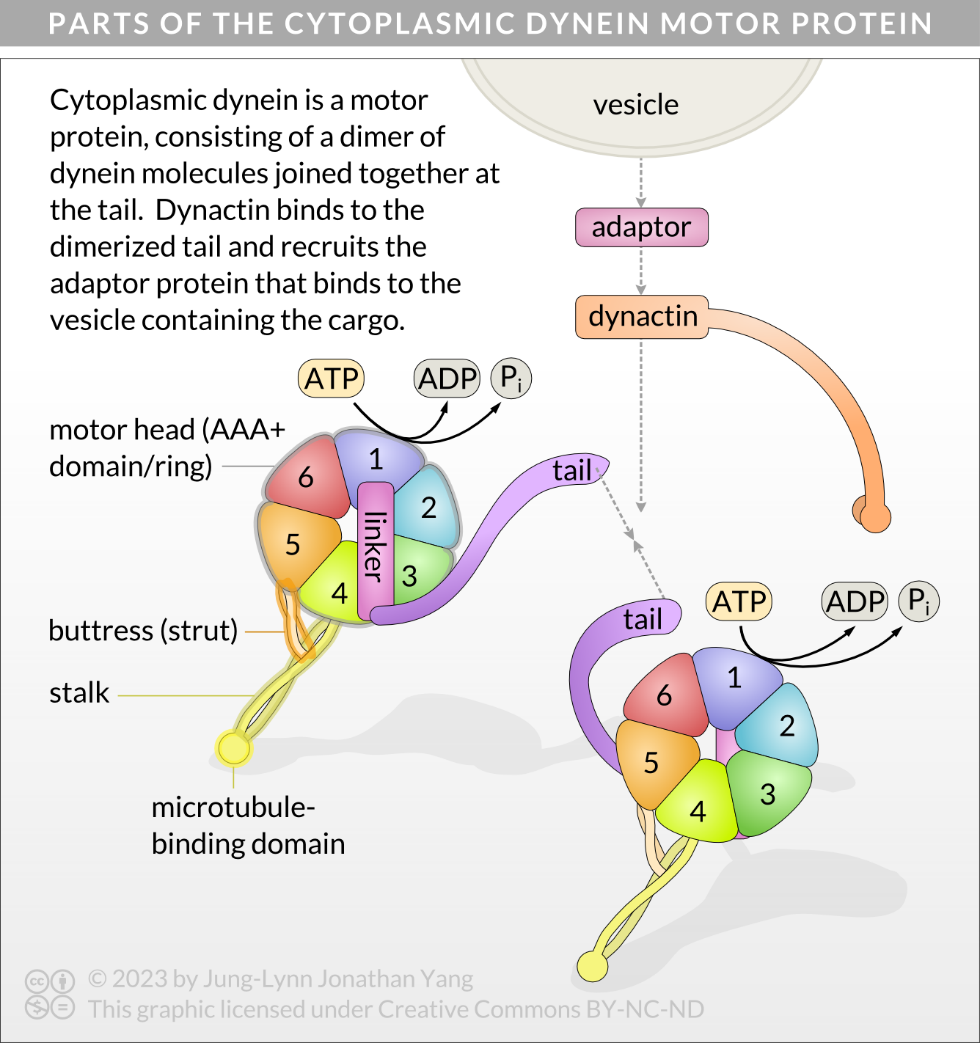

Cytoplasmic dyneins are large proteins with two identical globular force-generating engines (heavy chain or globular heads) and other associated chains and accessory proteins that bind cargo (Figure 8).4 Dyneins consist of two or three heavy chains (each about 500 kDa) complexed with a variable number of light and intermediate polypeptides, ranging from 14 to 120 kDa. The stalk of the heavy chain is a coiled-coil connecting the microtubule-binding domain to the AAA+ (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) ring, and the light chains (tail) at the C-terminus bind to cargo (Figure 9B).5 The buttress is a smaller coiled-coil that interacts with the stalk approximately one-third up the stalk from the ring.6 The AAA+ ring has six domains, numbered as AAA1 to AAA6, arranged like a wheel. Much about the AAA+ domains remains unknown4, but AAA1 has become well established as the primary site of ATP hydrolysis in dynein.7 A linker also connects the dimerization domain of the cargo-binding tail with the AAA+ ring. The linker changes conformation after ATP binds to AAA1.

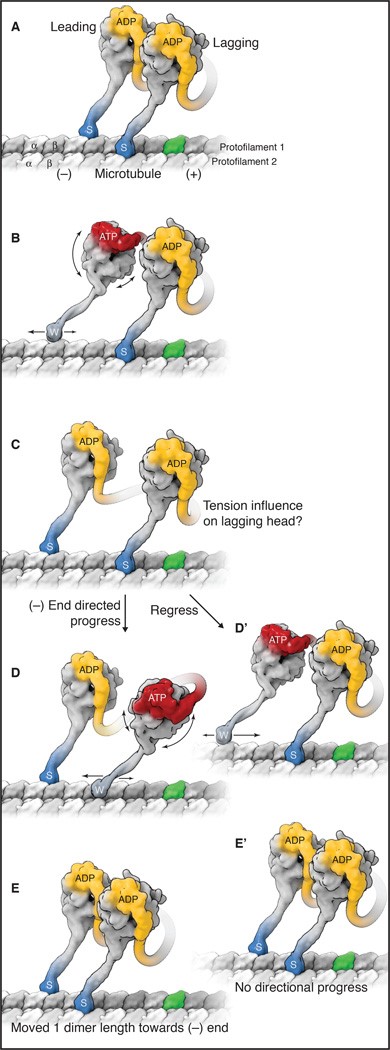

Mechanochemical Cycle of Cytoplasmic Dynein

Like kinesin, cytoplasmic dynein exhibits processive movement and must have one head strongly bound to a microtubule while the other detaches and advances (Figure 9). Much about the AAA+ domains remains unknown,6 but AAA1 is well established as the primary site of ATP hydrolysis in dynein.8 The events in Figure 9 can be summarized as follows:

- Cytoplasmic dynein dimer binds with ADP in both motor domains (yellow). This is the strong microtubule-binding state (indicated by “s” and darker blue colour).

- The wheel changes shape when ADP gets exchanged for ATP in the leading head (red). This exchange causes a conformational change in AAA1, movement of the buttress,9 and changes the angle of the stalk to point it forward on the microtubule track. This is the weak microtubule-binding state (indicated by “w”). The conformational change also causes the linker to bend (red) and the stalk to detach from the microtubule. The leading head moves toward the minus end.

- Following ATP hydrolysis, the stalk rotates, moving dynein further along the microtubule.10 Upon releasing the phosphate, the microtubule-binding domain returns to a high-affinity state and rebinds the microtubule (indicated by “s”), triggering the power stroke.7 The linker returns to a straight conformation and swings back to AAA5 from AAA211,12 and creates a lever-action,13 producing the most significant displacement of dynein achieved by the power stroke.10

- The lagging head detaches after exchanging ADP for ATP and gets pulled forward by the leading head.

- ATP hydrolysis in lagging head solidifies microtubule binding.

Axonal Transport

Although cytoplasmic transport occurs in all eukaryotic cells, a particularly well-studied case is axonal transport (also called axoplasmic transport) in neurons. Here, transporting materials from the cell body (soma) to the tips of the axons can sometimes traverse very long distances (up to several metres in larger animals), and they must do so in a timely manner. Axonal transport is generally either anterograde (from soma to axon terminal) or retrograde (from terminals back). The types of material transported in these two directions are very different: much of the anterograde transport is protein building blocks for extending the axon or synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters; retrograde transport is mostly endocytic vesicles and signalling molecules. Axonal transport can be either fast or slow. Slow transport is primarily the movement of proteins directly bound to the motors and can move 3-100 mm per day. Fast transport, in comparison, generally moves vesicles and can vary from 50 to 400 mm per day. The debate about the mechanism of slow transport happened for over a decade until 2000 when direct visualization of fluorescently labelled neurofilaments in transport showed that the actual movement of the proteins was very similar to the movement in fast axonal transport. However, slow transport involves many pauses, known as a “stop and go” mechanism, rather than continuously moving from source to destination.

Learning Activity: Cytoplasmic Dynein — Structure and Function

- Read the article “First glimpses of motor proteins in action” [14, Imai et al] by Chris Bunting (2015).

- Watch the associated video “Motor proteins caught “swinging on monkey bars” (4:08 min) by the University of Leeds (2015).

- Watch the video “Dynein Motor Protein” (3:00 min) by Molecular Animations of the Cell (2022).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the videos and article:

- How are dynein proteins similar to kinesins in terms of general function?

- List three roles of dynein within the cell.

- What are the names of the engines, how many are there and to what other parts of the dynein molecule do they connect?

- Which engine is the most important? What is it connected to?

- Which domain is continuous with the stalk? What is on the microtubule end of it?

- What protein complex does dynein need to bind before connecting with a microtubule?

- What is the first step in dynein action? What are two consequences?

- What happens after the head binds the microtubule?

- Why do viruses hijack motor proteins?

- How did the University of Leads’ team get a closer look at dynein structure and function? What type of microscopy did they use?

Learning Activity: Summary — Cytoskeletal Molecular Motor Proteins I

- Go to the Cytoskeletal Motor Proteins by Science Communication Lab (2019) from the Cell Biology Flipped Course. Scroll down slightly and click on “Start pathway.”

- Watch video 1 “Molecular Motor Proteins” (35:25 min) (2019) in this three-part series by Dr. Ron Vale, one of the discoverers of kinesin motor proteins. This video touches on kinesin and myosin. A transcript is also available.

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in this video.

- What types of cytoskeletal elements act as tracks for motor proteins?

- Describe microtubule polarity and how it relates to the directional movements of dynein and kinesin.

- Where is actin located within cells?

- How many genes are there for the various kinesin, myosin, and dynein proteins?

- What are the parts of kinesin motor proteins? Which part walks along the microtubule? Which part carries cargo?

- Why do the tails differ so much between different kinesin proteins?

- What parts of the different kinesin proteins are similar, and which are different?

- What do the motor domains do?

- Some organisms have melanocytes with pigment-containing melanosomes. Why do they need kinesin or dynein to move the melanosomes around?

- Which of the three cytoskeletal structures does the myosin motor protein interact with?

- What are three ways to study motor protein function using in vitro motility assays?

- What techniques can you use to visualize motor proteins?

- What are two parts common to motor proteins?

- Describe the movement of muscle myosin in response to its nucleotide state, as explained by Dr. Vale.

- What is the mechanical element of kinesin called?

- Describe the movement of kinesin in response to its nucleotide state as explained by Dr. Vale.

- List and briefly describe two diseases associated with altered dynein and kinesin protein function.

Learning Activity: Summary — Cytoskeletal Molecular Motor Proteins II

- Go to the Cytoskeletal Motor Proteins by Science Communication Lab (2019) from the Cell Biology Flipped Course. Scroll down slightly and click either Video 2 or “Start pathway” then “Next.”

- Watch video 2 “Molecular Motor Proteins: The Mechanism of Dynein Motility” (39:36 min) (2019) in this three-part series by Dr. Ron Vale. This video touches on dynein motor proteins, and a transcript is also available.

- Answer the following questions based on the information provided in this video.

- Why do we not know as much about dynein as we do about kinesin?

- What are axonemal dyneins?

- Draw the structure of an outer microtubule doublet found in the axonemes of cilia.

- To which tubule of the outer microtubule doublet do the inner and outer dynein arms connect? Add these connections to your diagram in c.

- What do cytoplasmic dyneins do?

- In what direction do cytoplasmic dyneins move? What is the name of the dynein responsible for most of the cellular transport of cargo?

- What types of cargo can be carried?

- How are AAA ATPases put together? What do they do?

- How can you use microscopy to view dynein moving processively along microtubule tracks?

- How can you watch the movement made by the dynein heads along a microtubule? Describe how dynein moves along a microtubule in comparison to kinesin.

- Which is the main ATPase subunit of the AAA ring that drives the motility of dynein? What is the second most important ATPase subunit?

- Draw and label the structural components that Dr. Ron Vale describes in colour.

- How does ATP binding affect the conformation of the AAA head of dynein?

- How does ATP binding to the AAA1 of dynein affect its affinity for microtubule binding?

- What happens to the linker when ATP binds?

- Put together all of the information above to describe dynein dimer motility.

- Use the video animations after the 30-minute time stamp and your text to draw and describe each of the events of dynein motility along a microtubule. Include the effects of the exchange of ATP for ADP, loss of Pi, changes in linker conformation, and effects of changes in AAA rotation and stalk movements.

- Describe in your own words how the binding of ATP to AAA1 is analogous to dominos, as explained by Dr. Ron Vale.

Axonemal Dynein Enables the Bending Motion of Flagella and Cilia

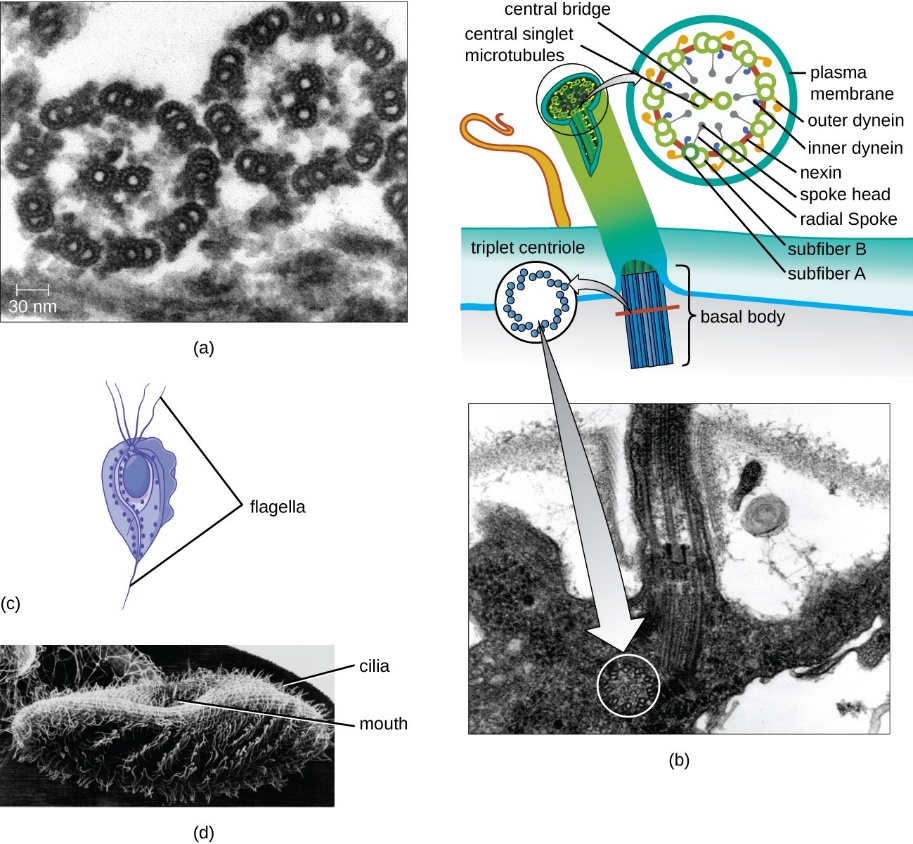

Microtubules are also crucial components of movement in specialized eukaryotic cell structures: flagella (singular flagellum) and cilia (singular cilium). Flagella are long, hair-like structures extending from the cell surface used to move an entire cell, such as a sperm. If a cell has any flagella, it usually has one or just a few. Motile cilia are structurally like flagella, but their shorter length means cilia use a rapid, flexible, waving motion. In addition to motility, cilia may have other functions, such as sweeping particles or pathogens past or into cells. Cilia and flagella, which differ primarily in length rather than construction, are microtubule-based organelles that move with a back-and-forth motion. This motion translates to “rowing” by the relatively short cilia; however, in the longer flagella, the flexibility of the structure causes the back-and-forth motion to propagate as a wave. In other words, the flagellar movement is more undulating or whiplike. Imagine these motions as a garden hose moving quickly from side to side compared to a short piece of the same hose moving in a similar way.

Prokaryotes also have flagella, which they use to move. The eukaryotic flagella have a similar role but a very different structure. While the prokaryotic flagellum is a stiff, rotating structure, the eukaryotic flagellum is more like a flexible whip.

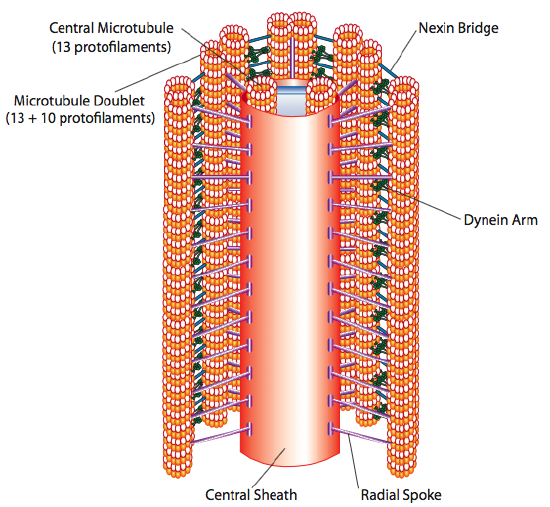

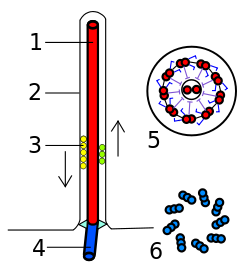

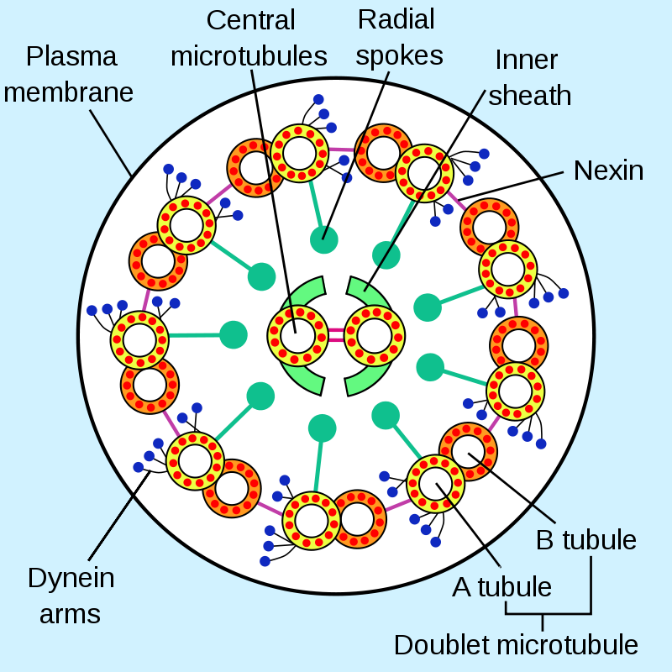

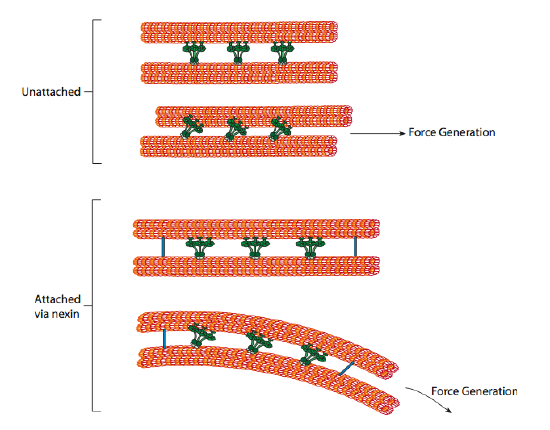

The core of both flagella and cilia is called the axoneme, which is composed of nine microtubule doublets connected by ciliary dynein motor proteins surrounding a central core of two separate microtubules (Figure 10, Figure 11, and Figure 12). This composition is known as the “9+2” array, although the nine doublets differ from the two central microtubules. The A tubule is a full 13 protofilaments, but the B tubule fused to it contains only 10 protofilaments. Each central microtubule is a full 13 protofilaments. The 9+2 axoneme extends the length of the cilium or flagellum from the tip until it reaches the base. It connects to the cell body through a basal body, which is composed of nine microtubule triplets arranged in a short barrel, much like the centrioles they derive from. Parallel microtubules use dynein motor proteins to slide relative to each other, causing the flagellum or cilium to bend or undulate in a wave-like motion.

Each cilium and flagellum has a basal body at its base (Figure 11b). The basal body, which attaches the cilium or flagellum to the cell, consists of an array of triplet microtubules, like a centriole, embedded in the plasma membrane. The basal body plays a crucial role in assembling the cilium or flagellum. Once the structure assembles, it alsoregulates which proteins can enter or exit.

Figure 12: (Left) Eukaryotic flagellum. 1-axoneme, 2-cell membrane, 3-IFT (intraflagellar transport), 4-basal body, 5-cross section of flagellum, 6-triplets of microtubules of basal body. (Right) A cross-section of an axoneme in a flagellum. Left: (Franciscosp2 2008/Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 3.0; Right: (Smartse 2009/Wikimedia Commons) CC BY-SA 3.0

Self-Check

- What are the similarities and differences between the structures of centrioles and flagella?

Show/Hide answer.

Centrioles and flagella are alike in that they consist of microtubules. In centrioles, two rings of nine microtubule “triplets” are arranged at right angles to one another. This arrangement does not occur in flagella, which has a 9+2 doublet arrangement of microtubules.

- How do cilia and flagella differ?

Show/Hide answer.

Cilia and flagella are alike in that they consist of microtubules. Cilia are short, hair-like structures that exist in large numbers and usually cover the entire plasma membrane surface. Flagella, in contrast, are long, hair-like structures; when flagella are present, a cell has just one or two.

In flagella and motile cilia, motor proteins called dyneins move along the microtubules, generating a force that causes the flagella or cilia to beat. The structural connections between the microtubule pairs and the coordination of dynein movement allow the motors to produce a pattern of regular beating, as shown in Figure 13.

The ciliary dyneins provide motor capability, but the axoneme has two additional linkage proteins: nexins and radial spokes. Nexins join the A tubule of one doublet to the B tubule of its adjacent doublet, thus connecting the outer ring. Meanwhile, radial spokes extend from the A tubule of each doublet to the central pair of microtubules at the core of the axoneme. Neither has any motor activity; however, they are crucial to the movement of cilia and flagella because they help transform a sliding motion into a bending motion. When ciliary dynein (very similar to cytoplasmic dynein but with three heads instead of two) engages, it binds an A microtubule on one side at the same time as a B microtubule from the adjacent doublet, and it moves one relative to the other. A line of these dyneins moving in concert would thus slide one doublet relative to the other if (and it is a big “if”) the two doublets had complete freedom of movement. However, since nexin proteins interconnect the doublets, one doublet attempting to slide bends the connected structure instead (Figure 13). This bend accounts for the rowing motion of the relatively short cilia and the whipping motion of the long flagella, which propagates the bending motion down the axoneme.

Lastly, viruses can exploit dynein and kinesin to mediate viral replication. Many viruses use the microtubule transport system to transport nucleic acid/protein cores to intracellular replication sites after invasion from the host cell membrane. Although there is little information about virus motor-specific binding sites, some viruses contain proline-rich sequences (that diverge between viruses) which, when removed, reduce dynactin binding, axon transport (in culture), and neuroinvasion in vivo. This characteristic suggests that proline-rich sequences may be a crucial binding site that co-opts dynein.

Learning Activity: Axoneme Structure of Cilia and Flagella

- Watch the video “Axoneme of Cilia and Flagella” (52 s) by Walter Jahn (2016).

- Answer the following question based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What are the names of all the components that make up an axoneme?

- How many of each component are there?

- Match the letters in the TEM of an axoneme to the structures listed.

Learning Activity: Origin of Cilia and Flagella

- Watch the video “Cytoskeleton Microtubules | Cell Biology” (4:49 min) by Greatpacificmedia (2009).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the video:

- Where do cilia and flagella come from originally in animal cells?

- How does the 9+2 arrangement form in cilia and flagella?

- How are cilia different from flagella?

Learning Activity: How do Cilia and Flagella Move?

- Watch the video “How do Cilia and Flagella Move?” (2:36 min) by XVIVO Scientific Animation (2020).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What technique was used to visualize the insides of sperm flagella?

- What happens to dynein movement for a flagellum to beat back and forth?

- Why does the flagellum bend in one direction?

Ciliary Dyskinesia

Although people think of ciliary and flagellar only as movement methods for the propulsion of a cell (e.g., the flagellar swimming of sperm towards an egg), cilia also get used in several important places where the cell is stationary to move fluid past the cell. In fact, most major organs of the body have cells with cilia. Several ciliary dyskinesias are known. The most prominent, primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), which includes Kartagener Syndrome (KS), is due to a mutation in the DNAI1 gene that encodes a subunit (intermediate chain 1) of axonemal ciliary dynein. The main characteristic of PCD is respiratory distress due to recurrent infection. A person gets diagnosed with KS if there is also situs inversus, a condition that reverses the normal left-right asymmetry of the body (e.g., stomach on the left, liver on the right). The first symptom is due to the inactivity of the numerous cilia of epithelial cells in the lungs. Their normal function is to keep mucus in the respiratory tract constantly in motion. The mucus usually helps keep the lungs moist to facilitate function; however, if it becomes stationary, it becomes a breeding ground for bacteria and an irritant and obstacle to proper gas exchange.

Situs inversus is an interesting malformation because it arises in embryonic development. It affects only 50% of PCD patients because the impaired ciliary function causes randomization of left-right asymmetry, not reversal. In simple terms, during early embryonic development, left-right asymmetry partly occurs due to molecular signals moving in a leftward flow through a structure called the embryonic node. The coordinated beating of cilia causes this flow, so when cilia do not work, the flow gets disrupted and causes randomization.

Other symptoms of PCD also relate to the work of cilia and flagella in the body. Male infertility is commonly due to immotile sperm. Female infertility, though less common, can also occur due to cilia dysfunction of the oviduct and fallopian tube that usually moves the egg along from the ovary to the uterus. Interestingly, PCD also has a low association with hydrocephalus internus (which is overfilling the ventricles in the brain with cerebrospinal fluid that causes them to enlarge and compress the brain tissue around them). This association is likely due to cilia dysfunction in the ependymal cells lining the ventricles, which help circulate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); however, these cilia may not be completely necessary. Since CSF bulk flow is thought to be driven primarily by the systole/diastole change in blood pressure in the brain, some hypothesize that the cilia may be mainly involved in flow through some tighter channels in the brain.

Learning Activity: Cilia — Nature’s Exquisite Nanomachines

- Watch the video “Scene 3: Cilia-Nature’s Exquisite Nanomachines” (4:53 min) by TheCISMM (2010).

- Answer the following questions based on your Unit 3, Topic 5 readings and the information provided in the video:

- What is the purpose of cilia in your respiratory system?

- How do cilia bend?

The Myosin Superfamily

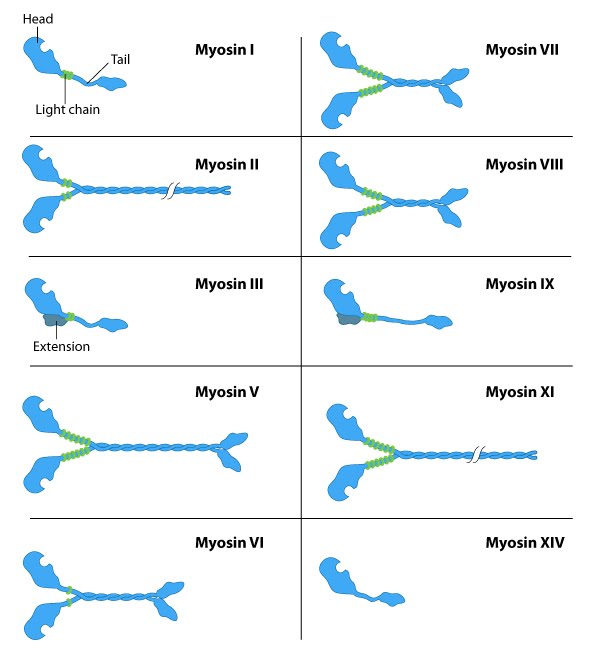

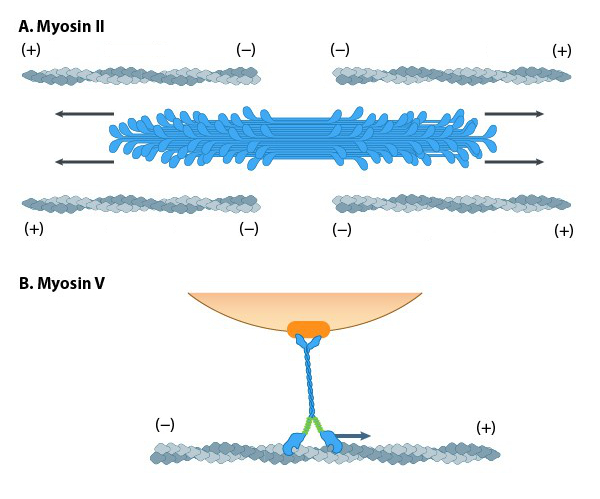

Actin filaments have several important roles in the cell. For one, they serve as tracks for the movement of the most commonly described motor proteins, the myosin superfamily. Some species of myosin live and function only in the nucleus; however, most myosins function as cytoplasmic motor proteins in many cellular events requiring motion.14,15 Actin and myosin are plentiful in muscle cells, where they form organized structures of overlapping myofilaments called sarcomeres. When sarcomere actin and myosin filaments slide past each other in concert, muscles in the body contract. Actin filaments may also serve as highways inside the cell for transporting cargo, including protein-containing vesicles and organelles. Individual myosin motors carry this cargo by “walking” along actin filament bundles.16 In animal cell division, a ring made of actin and myosin pinches the cell apart to generate two new daughter cells during cytokinesis.

Myosin Motor Protein Structure

Eukaryotes have several myosin isoforms, sorted into distinct classes numbered in Roman numerals. All myosins consist of a diverse ‘tail’ domain at their carboxy terminus and an evolutionarily conserved globular ‘head’ domain at the amino terminus of their heavy chains. Each myosin class differs by the heavy and light chains they are composed of (Figure 14).

The diverse ‘tails’ of different myosin isoforms bind specific substrates or cargo, and their conserved ‘heads’ contain sites for ATP binding17, F-actin binding and force generation (i.e., motor domains)reviewed in 14,18. All myosins bind to actin filaments via a globular ‘head’ domain at the end of the heavy chains. Actin binding to this region increases the ATPase activity of myosinsreviewed in 19. Some myosins have a single heavy chain and contact actin filaments at only one site, while other myosin isoforms have two heavy chains and contact actin filaments at two sites.

The number of light chains influences the length of the “lever arm” or “neck region” and, therefore, the “step size” of different myosin types.15 Myosin V contains more light chains and a longer ‘lever arm’ relative to myosin II and so myosin V moves in larger steps along actin filaments after an equivalent round of ATP hydrolysisreviewed in 20,21.

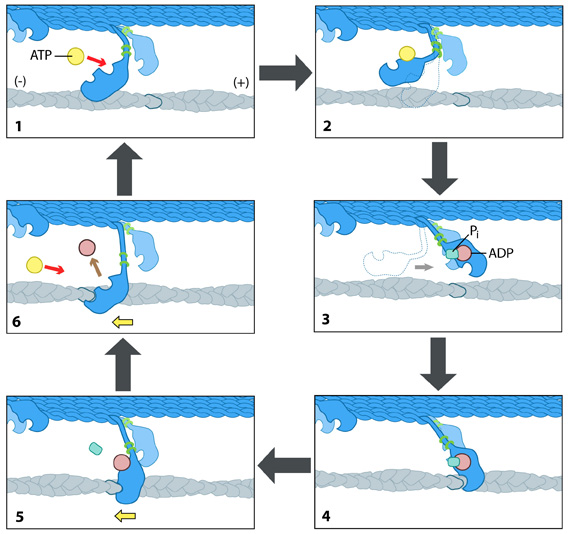

Mechanochemical Cycle of Myosin II

Each myosin motor protein possesses ATPase activity and functions cyclically by coupling ATP binding and hydrolysis to cause a conformational change in the protein. This process is known as the ‘power stroke cycle’ and is outlined in Figure 15 using myosin II as an example.

Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore

The structural orientation of myosin in relation to the filament dictates the direction in which the actin filament moves. A complete round of ATP hydrolysis produces a single ‘step’ or movement of myosin along the actin filament. The changes in the concentration of intracellular free calcium regulate this process. The steps involved are detailed below:

- Step 1 — At the end of the previous round of movement and the start of the next cycle, the myosin head lacks a bound ATP. It attaches to the actin filament in a very short-lived conformation known as the ‘rigour conformation.’

- Step 2 — ATP binding to the myosin head domain induces a small conformational shift in the actin-binding site, reducing its affinity for actin and causing the myosin head to release the actin filament.

- Step 3 — ATP binding also causes a large conformational shift in the ‘lever arm’ of the myosin light chain that bends the myosin head into a position further along the filament. ATP undergoes hydrolysis, leaving the inorganic phosphate and ADP bound to myosin.

- Step 4 — The myosin head makes weak contact with the actin filament, and a slight conformational change occurs on myosin that promotes the release of the inorganic phosphate.

- Step 5 — Releasing inorganic phosphate reinforces the binding interaction between myosin and actin, subsequently triggering the ‘power stroke.’ The power stroke is the crucial force-generating step used by myosin motor proteins. Forces are generated on the actin filament as the myosin protein reverts back to its original conformation.

- Step 6 — As myosin regains its original conformation, it releases the ADP; however, the head remains tightly bound to the filament at a new position from where it started, bringing the cycle back to the beginning.

Myosin Motors for Muscle Contraction and Intracellular Transport

A variety of class II myosins are best known for their roles in muscle contraction but also function in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. Myosin II is the only class of myosins that can form higher-order assemblies via the extended coiled-coil domains in the heavy chains. The long coiled-coil domains of myosin II interact with the coiled-coiled domains of adjacent myosin II molecules, followed by additional tail-tail interactions with other myosin II assemblies. The resulting myosin II bundle (“thick filament”)14 has several hundred myosin heads oriented in opposite directions at the two ends of the filament. Concerted ATP hydrolysis and movement of the myosin heads along adjacent actin filaments generate a sliding motion that results in the shortening or contraction of the interlinked actin filaments and skeletal muscles (Figure 16A). The action of the actin-myosin system generates forces against the interlinked cytoskeleton network to influence processes such as cell signalling, adhesion, movement, polarity, and cell fate (see “contractile bundle” in Key Terms)reviewed in 19; 22,23,24. Myosin II is also a critical component of stress fibres and the contractile ring that separates two cells during cell division. Myosin II is also associated with retraction fibres and retrograde actin flow at the pointed (−) end of actin filaments. All non-muscle cells use contractile bundles containing myosin II to generate forces that promote the assembly of actin filaments.

In non-muscle cells, actin filaments form an internal track system for cargo transport powered by motor proteins such as myosin V (Figure 16B) and myosin VI; these myosin proteins use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to transport cargo (such as attached RNA, vesicles and organelles) at rates much faster than diffusion. Myosin motors are functionally similar to kinesin motors for intracellular transport. The difference is that myosins walk on actin filaments, and kinesins use microtubules. Therefore, myosins tend to transport over shorter distances than kinesins because actin filaments are generally shorter than microtubules. With the exception of myosin VI, which moves towards the pointed end, all myosins move towards the barbed (+) end of actin filaments. Most actin filaments have the barbed end directed towards the plasma membrane and the pointed end towards the interior. This arrangement allows specific myosins (e.g., myosin V) to function primarily for cargo export. Myosin VI acts as the principal motor protein for import. Myosin V, VII, and X also regulate filopodial assembly and extension.

Mechanobiology Institute, National University of Singapore.

Learning Activity: Myosin Structure and Function

- Watch the video “032-Myosin Structure & Function” (8:21 min) by Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2014).

- Answer the following questions:

- Describe and draw the overall general structure of myosin using terminology from the video.

- Label this space-filling model of myosin using information from the video and the Unit 3, Topic 5 text. Include the following parts: head, neck, lever arm, light chain, the amino terminus of the heavy chain, ATP-binding pocket, and actin-binding site.

- What part of the myosin protein structure contacts the actin filaments?

- What part of the myosin protein structure interacts to form bundles of the thick filaments?

- Describe how the myosin head region is bound to actin before and after it binds to ATP.

- What is the result of myosin’s ATPase activity after binding ATP? What is the power stroke?

Actomyosin Ring Separates Daughter Cells During Cytokinesis

Toward the end of telophase, sister chromatids migrate to opposite poles of the cell and enter the next phase of cell division called cytokinesis. In order to divide the cytoplasm into two daughter cells, bundles of actin filaments and myosin II form a contractile ring called the actomyosin ring. The actomyosin ring is located just inside the plasma membrane, at the former metaphase plate, and oriented perpendicularly to the axis of the spindle apparatus (Figure 17).25,26 The myosin motor protein pulls on actin filaments such that the ring constricts the equator of the cell, forming the cleavage furrow. The furrow deepens as the ring contracts, and eventually, the membrane and cell are cleaved in two. The action of the actomyosin ring follows an orderly sequence of events: identification of the active division site, formation of the ring, constriction of the ring, and disassembly of the ring.25 Watch the actomyosin ring in motion in the following Learning Activity.

Learning Activity: Formation of the Actomyosin Ring

- Watch the video “Cytokinesis in vertebrate cells initiates by contraction of an equatorial actomyosin network” (52 s) by ScienceVio (2017) (Spira et al., 2017).

- Answer the following questions:

- What type of microscopy was used by the researchers to visualize the actomyosin ring during cytokinesis in human cells? Go to the cited primary research article, “Cytokinesis in vertebrate cells initiates by contraction of an equatorial actomyosin network composed of randomly oriented filaments” by Spira et al. (2017), associated with this video to answer this question.

- What is Lifeact? How is it used to visualize actin filaments within cells? Scroll down to Video 1 in the above primary research article. Under the video, it states that the cells were expressing Lifeact-mCherry. Go to the article “Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin” by Riedl et al. (2008) to answer this question.

- What is mCherry?

Learning Activity: Summary of Cytoskeleton Structure and Function

- Watch the video “Cytoskeleton Structure and Function” (9:16 min) by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

- Complete the following tasks:

- Write down all aspects of the cytoskeleton that you feel comfortable explaining.

- Describe your favourite aspect of the cytoskeleton.

Self-Check

- Aneuploidogens are chemicals that may disrupt gamete formation by interfering with spindle formation and the last phase of cell division. As a result, the embryo may have abnormal ploidy. Based on this information, which cytoskeletal structures and cell division process are affected by aneuploidogens?

- Microtubules and cytokinesis, respectively

- Intermediate filaments and mitosis, respectively

- Microfilaments and telophase, respectively

- Microfilaments and spermatogenesis, respectively

Show/Hide answer.

a. Microtubules and cytokinesis, respectively

- Drag the best term for each box in the figure:

- Match each of the following functions to each cytoskeletal structure:

Key Concepts and Summary

Motor proteins couple the mechanical process of movement with chemical processes of ADP/ATP exchange and hydrolysis. These movements can be visualized by in vitro motility assays using fluorescence microscopy of GFP-coupled motors and fluorescently labelled microtubules. Controlled hydrolysis of nucleotides and inorganic phosphate release by motor proteins can generate mechanical forces used for:

- Translocating the motor proteins themselves along the filaments

- Stabilizing and/or moving the filaments (i.e., contractile stress fibres) and escorting cargo that is attached to the motor protein (e.g., vesicles, organelles, other proteins) to specific regions in the cell

- Transporting substances in a particular direction, or polarity, along the filaments

- This directionality occurs due to specific conformational changes that allow movement in only one direction.

Motor proteins propel themselves along the cytoskeleton using a mechanochemical cycle of filament binding, conformational change, filament release, conformational reversal, and filament rebinding. In most cases, the conformational change(s) on the motor protein prevents subsequent nucleotide binding and/or hydrolysis until the prior round of hydrolysis and release is complete.

Microtubule Motor Proteins — Kinesin and Dynein

The motor proteins kinesin and dynein couple ATP binding and hydrolysis to cause conformational changes that allow them to move along microtubules. Both kinesins and dyneins bind cargo (vesicles or organelles) through their light chains. A variety of kinesins move toward the plus ends of microtubules (anterograde), while dyneins are less diverse and move in the opposite direction (retrograde). Many kinesin families show great processivity because they travel long distances on microtubules before falling off.

Cytoplasmic and axonemal dynein proteins move along microtubules by combining changes in the orientation of their ring-shaped AAA+ domain with ATP binding and hydrolysis. Cytoplasmic ATP-bound dynein attaches loosely to microtubules, while ADP-bound dynein is strongly bound. Dynein uses ATP binding to release from the microtubule and swing its stalk forward toward the minus end. ATP hydrolysis and inorganic phosphate release return dynein to its high-affinity binding state on the microtubule.

Axonemal dynein powers the movement of cilia and flagella, which have a 9+2 arrangement of microtubules. Outer and inner dynein arms contact the A tubule of the adjacent doublet and move it relative to the B tubule to which it is attached. A bending instead of sliding motion occurs due to the linkage protein nexin.

Microfilament-Based Motility — Myosin

Myosin motor proteins also use the power of ATP hydrolysis to make conformational changes required for movement through their head regions. There are a variety of myosin proteins. Myosin II is involved in muscle contraction. Non-muscle myosin (myosin I) contacts actin through its head region and binds vesicles through its tail to move cargo toward the plus ends of microfilaments. Myosin functions include:

- Vesicular transport

- Cytoplasmic streaming

- Endocytosis

- Skeletal and cardiac muscle contraction

- Cytokinesis by actomyosin contraction

- Cell crawling by the myosin-mediated, leading-edge formation and trailing-edge contraction

Key Terms

axoneme

the microtubule-based cytoskeletal structure that forms the core of a cilium or flagellum arranged as nine outer microtubule doublets and one inner doublet

basal body

a structure containing microtubules that develops from centrioles from which axonemes of cilia and flagella develop

B tubule

an incomplete microtubule that is connected to the A tubule in an axoneme of a eukaryotic flagellum or cilium

centriole

a structure consisting of nine sets of triplet microtubules embedded in the centrosome of animal cells

centrosome

a complex that serves as the primary microtubule organizing centre of animal cells; composed of two centrioles arranged at right angles to each other

cilium (plural cilia)

short, hair-like structure that extends from the plasma membrane in large numbers and functions to move an entire cell or move substances along the cell’s outer surface

contractile bundle

the contractile bundles in nonmuscle cells are similar to skeletal muscle fibres, but they are smaller (~0.4 µm in fibroblasts), less organized, and they contain different accessory proteins

contractile ring

an actomyosin contractile ring that is a prominent structure during cytokinesis; forms perpendicular to the axis of the spindle apparatus towards the end of telophase

dynein

a motor protein ATPase that carries out retrograde minus-end movement along microtubules in the cytoplasm; responsible for movement as axonemal dynein in cilia and flagella

dynactin

a complex of proteins that connects cytoplasmic dynein to its cargo

flagellum (plural flagella)

long, hair-like structure that extends from the plasma membrane and moves the cell

kinesin

a superfamily of ATP-dependent motor proteins that move toward the plus end of microtubules using intrinsic ATPase activity

nexin

a protein that connects adjacent outer double microtubules in the axonemes of eukaryotic cilia and flagella

outer doublet

a pair of fused microtubules (one complete/one incomplete) in the axonemes of eukaryotic cilia and flagella

radial spoke

a multi-unit protein structure known to play a role in the mechanical movement of the eukaryotic flagellum/cilium

retrograde transport

movement of vesicles away from the plasma membrane

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: Figure 12.6.7 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 2: Figure 1-9 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 3: Kinesin transports cargo along microtubules by Mechanobiology Institute (2023)

- Figure 4: (Left) Figure 1-8 from Fundamentals of Cell Biology (Katzman et al. 2020) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: The Kinesin Powerstroke by Mechanobiology Institute (2023)

- Figure 6: Mechanochemical cycle of kinesin… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2023) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 7: Fluorescent visualization of kinesin… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2023) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 8: Domains of cytoplasmic dynein… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2023) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

- Figure 9: Figure 2 by Bhabha et al. (2016) is used with permission from the author.

- Figure 10: Figure 12.9.16 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 11: OSC Microbio 03 04 Flagellum by CNX OpenStax (2016), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 12: (Left) Eukarya Flagella by Franciscosp2 (2008), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license. (Right) Eukaryotic flagellum by Smartse (2009), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 13: Figure 12.9.17 from Cells – Molecules and Mechanisms (Wong) (Wong 2022) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 14: Myosin motor protein structure by Mechanobiology Institute (2023) used with permission.

- Figure 15: The “power stroke” mechanism… by Mechanobiology Institute (2023) used with permission.

- Figure 16: Different motor protein functions… by Mechanobiology Institute (2023) used with permission.

- Figure 17: The actomyosin ring… by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang (2023) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

References

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. 2002. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th ed. New York (NY): Garland Science; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21054/.

1 Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. 2002. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th ed. New York (NY): Garland Science; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Molecular motors. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26888/.

7 Bhabha G, Johnson GT, Schroeder CM, Vale RD. 2016. How dynein moves along microtubules. Trends Biochem Sci. 41(1):94-105. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968000415002121?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.004.

Bunting C. 2015. First glimpses of motor proteins in action [article]. Leeds (England): University of Leeds; [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.leeds.ac.uk/news/article/3754/.

12 Burgess SA, Knight PJ. 2004. Is the dynein motor a winch? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 14(2):138-146. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X04000478?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.013.

19 Cai Y, Sheetz MP. 2009. Force propagation across cells: mechanical coherence of dynamic cytoskeletons. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 21(1):47-50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955067409000325?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.020.

4 Canty JT, Tan R, Kusakci E, Fernandes J, Yildiz A. 2021. Structure and mechanics of dynein motors. Annu Rev Biophys. 50:549-574. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-biophys-111020-101511. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-111020-101511.

5 Carter AP, Vale RD. 2010. Communication between the AAA+ ring and microtubule-binding domain of dynein. Biochem Cell Biol. 88(1):15-21. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/O09-127. doi:10.1139/O09-1127.

25 Cheffings TH. Burroughs NJ, Balasubramanian MK. 2016. Actomyosin ring formation and tension generation in eukaryotic cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 26(15):R719-R737. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096098221630745X?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.071.

14 Cheney RE, Riley MA, Mooseker MS. 1993. Phylogenetic analysis of the myosin superfamily. Cytoskeleton. 24(4):215-223. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cm.970240402. doi:10.1002/cm.970240402.

CNX OpenStax. 2016. OSC microbio 03 04 flagellum [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated2016 Dec 2; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OSC_Microbio_03_04_Flagellum.jpg.

Cooper GM. 2000. The cell: a molecular approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9839/.

16 Cooper GM. 2000. The cell: a molecular approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Microtubule motors and movements. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9833/.

Cytopirate Labs. Kinesin walking on microtubules [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Jun 9, 0:29 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6g5icw1Zos.

24 Even-Ram S, Doyle AD, Conti MA, Matsumoto K, Adelstein RS, Yamada KM. 2007. Myosin IIA regulates cell motility and actomyosin–microtubule crosstalk. Nat Cell Biol. 9:299-309. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncb1540. doi:10.1038/ncb1540.

Franciscosp2. 2008. Eukarya flagella [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2008 Jul 21; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eukarya_Flagella.svg.

Fundamentals of Biochemistry. 032-myosin structure & function [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Jun 10, 8:21 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9SVGQTkDSxU.

Fundamentals of Biochemistry. 033-kinesin structure & function [Video]. YouTube. 2014 Jun 10, 7:06 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FwNVHiTOANM.

11 Gennerich A, Carter AP, Reck-Peterson SL, Vale RD. 2007. Force-induced bidirectional stepping of cytoplasmic dynein. Cell. 131(5):952-965. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867407012871?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.016.

Graham Johnson. Kinesin walking narrated version for Garland [Video]. 2011 Apr 7, 2:08 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAva4g3Pk6k.

Greatpacificmedia. Cytoskeleton microtubules | cell biology [Video]. YouTube. 2009 Oct 21, 4:49 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rqbmLiSkpk.

2 Hardin J, Bertoni G. 2016. Becker’s world of the cell. 9th ed. London (England): Pearson.

Harvard Medical School. Molecular motor struts like drunken sailor [Video]. YouTube. 2012 Jan 6, 0:30 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7AQVbrmzFw.

18 Hwang W, Lang MJ. 2009. Mechanical design of translocating motor proteins. Cell. Biochem Biophys. 54:11-22. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12013-009-9049-4. doi:10.1007/s12013-009-9049-4.

Imai H, Shima T, Sutoh K, Walker ML, Knight PJ, Kon T, Burgess SA. 2015. Direct observation shows superposition and large scale flexibility within cytoplasmic dynein motors moving along microtubules. Nat Commun. 6(8179). https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms9179. doi:10.1038/ncomms9179.

6 Kardon JR, Vale RD. 2009. Regulators of the cytoplasmic dynein motor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10:854-865. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm2804. doi:10.1038/nrm2804.

Kerr S, Weigel E, Spencer C, Garton D. 2023. Organismal biology. Atlanta (GA): Georgia Tech School of Biological Sciences; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu/.

Kerr S, Weigel E, Spencer C, Garton D. 2023. Organismal biology. Atlanta (GA): Georgia Tech School of Biological Sciences; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Motor proteins and muscles. https://organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu/chemical-and-electrical-signals/effectors-and-movement/.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/projects/fundamentals-of-cell-biology.

Katzman SD, Barrera AL, Higgins R, Talley J. Hurst-Kennedy J. 2020. Fundamentals of cell biology. Athens (GA): University System of Georgia; [accessed 2024 Jan 18]. Chapter 1: cytoskeleton. Figures 1-8, 1-9. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/fundamentals-of-cell-biology/section/301523e1-6d5d-488f-8dce-e73b46200340.

Khan Academy. [date unknown]. The cytoskeleton. Mountain View (CA): Khan Academy; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Biology library, Lesson 3: tour of a eukaryotic cell. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/structure-of-a-cell/tour-of-organelles/a/the-cytoskeleton.

3 Lodish H, Berk A, Kaiser CA, Krieger M, Bretscher A. 2016. Molecular cell biology. 8th ed. New York (NY): W H Freeman & Co.

26 Mana-Capelli S, McCollum D. 2013. Actomyosin ring. Encycl Syst Biol. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-9863-7_779. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9863-7_799.

Management. 2023. What is myosin? Queenstown (Singapore): Mechanobiology Institute; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://www.mbi.nus.edu.sg/mbinfo/what-is-myosin/.

8 Mocz G, Gibbons IR. 2001. Model for the motor component of dynein heavy chain based on homology to the AAA family of oligomeric ATPases. Structure. 9(2):93-103. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0969212600005578?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00557-8.

Molecular Animations of the Cell. Dynein motor protein [Video]. YouTube. 2022 Jan 7, 3:00 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGc6pkpU8qM.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science. Cytoskeleton structure and function [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Aug 3, 9:16 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTv9ItGd050.

13 Reck-Peterson SL, Yildiz A, Carter AP, Gennerich A, Zhang N, Vale RD. 2006. Single-molecule analysis of dynein processivity and stepping behavior. Cell. 126(2):335-348. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867406008622?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.046.

Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb A, et al. 2008. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat Methods. 5:605-607. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1220. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1220.

10 Roberts AJ, Numata N, Walker ML, Kato, YS, Malkova B, Kon T, Ohkura R, Arisaka F, Knight PJ, Sutoh K, et al. 2009. AAA+ ring and linker swing mechanism in the dynein motor. Cell. 136(3):485-495. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867408016000?via%3Dihub. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.049.

21 Ruppel KM, Spudich JA. 1996. Structure-function analysis of the motor domain of myosin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 12:543-573. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.543. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.543.

9 Schmidt H, Zalyte R, Urnavicius L, Carter AP. 2015. Structure of human cytoplasmic dynein-2 primed for its power stroke. Nature. 518:435-438. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14023. doi:10.1038/nature14023.

Science Communication Lab. 2019. Cytoskeletal motor proteins [Video]. Cambridge (MA): LabXchange; [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/pathway/lx-pathway:d330a34b-5999-4053-a02b-442089f72166.

Science Communication Lab. 1. molecular motor proteins [Video]. LabXchange. 2019 Aug 14, 35:25 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/pathway/lx-pathway:d330a34b-5999-4053-a02b-442089f72166/items/lb:LabXchange:0d2fe278:video:1/57100.

Science Communication Lab. 2. molecular motor proteins: the mechanism of dynein motility [Video]. LabXchange. 2019 Aug 15, 39:36 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.labxchange.org/library/pathway/lx-pathway:d330a34b-5999-4053-a02b-442089f72166/items/lb:LabXchange:5cd0f221:video:1/57101.

ScienceVio. Cytokinesis in vertebrate cells initiates by contraction of an equatorial actomyosin network [Video]. YouTube. 2017 Nov 6, 0:52 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8t4FEBYLSuE.

22 Shelden E, Knecht DA. 1995. Mutants lacking myosin II cannot resist forces generated during multicellular morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 108(3):1105-1115. https://journals.biologists.com/jcs/article/108/3/1105/24457/Mutants-lacking-myosin-II-cannot-resist-forces. doi:10.1242/jcs.108.3.1105.

Smartse. 2009. Eukaryotic flagellum [Image]. Wikimedia Commons; [updated 2009 Jul 14; accessed 2024 Jan 24]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9423365.

Spira F, Cuylen-Haering S, Mehta S, Samwer M, Reversat A, Verma A, Oldenbourg R, Sixt M, Gerlich DW. 2017. Cytokinesis in vertebrate cells initiates by contraction of an equatorial actomyosin network composed of randomly oriented filaments. eLife. 6(e30867). https://elifesciences.org/articles/30867. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30867.

TED. Animations of unseeable biology | Drew Berry | TED [Video]. YouTube. 2012 Jan 12, 9:08 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WFCvkkDSfIU.

TheCISMM. Scene 3: cilia-nature’s exquisite nanomachines [Video]. YouTube. 2010 Sep 22, 4:53 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQ3CdSiVzUk.

20 Trybus KM. 2008. Myosin V from head to tail. Cell Mol Life Sci. 65:1378-1389. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00018-008-7507-6. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7507-6.

UC San Francisco (UCSF). What is kinesin? Ron Vale explains. YouTube. 2018 Apr 2, 3:39 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBo_o0iO68U.

University of Leeds. Motor proteins caught “swinging on monkey bars” [Video]. YouTube. 2015 Sep 11, 4:08 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpjcW-ltOFo.

15 Uyeda TQ, Abamson PD, Spudich JA. 1996. The neck region of the myosin motor domain acts as a lever arm to generate movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 93(9):4459-4464. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.93.9.4459. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.9.4459.

Vale R. 2019. Motility in a test tube. San Francisco (CA): The Explorer’s Guide to Biology; [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://explorebiology.org/learn-overview/cell-biology/motility-in-a-test-tube.

23 Vicente-Manzanares M, Zareno J, Whitmore L, Choi CK, Horwitz AF. 2007. Regulation of protrusion, adhesion dynamics, and polarity by myosins IIA and IIB in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 176(5):573-580. https://rupress.org/jcb/article/176/5/573/34522/Regulation-of-protrusion-adhesion-dynamics-and. doi:10.1083/jcb.200612043.

17 Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha‐ and beta‐subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP‐requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1(8):945-951. https://www.embopress.org/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x.

Walter Jahn. Axoneme of cilia & flagella [Video]. YouTube. 2016 Aug 18, 0:52 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TnjCPg4kbEE.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Actin. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Dec 11; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Actin&oldid=1189363625.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Axoneme. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Sep 19; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Axoneme&oldid=1176089650.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Filopodia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Dec 3; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Filopodia&oldid=1188121816.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Integrin. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Nov 13; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Integrin&oldid=1184850634.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Intraflagellar transport. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Dec 3; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Intraflagellar_transport&oldid=1188137398.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2023. Radial spoke. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; [updated 2023 Nov 5; accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Radial_spoke&oldid=1183580008.

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

Wong EV. 2022. Cells – molecules and mechanisms (Wong). Louisville (KY): Axolotl Academic Publishing; [accessed 2024 Jan 22]. Chapter 12.6: transport on the cytoskeleton. Figures 12.6.7, 12.9.16, 12.9.17. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Cell_and_Molecular_Biology/Book%3A_Cells_-_Molecules_and_Mechanisms_(Wong).

XVIVO Scientific Animation. How do cilia and flagella move? [Video]. YouTube. 2020 Mar 10, 2:36 minutes. [accessed 2024 Jan 29]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nZYlyFGm50.

Yang J-L J. 2022. Figures 6, 7, 8, 17 created for this course.

short, hair-like structure that extends from the plasma membrane in large numbers and functions to move an entire cell or move substances along the cell’s outer surface

long, hair-like structure that extends from the plasma membrane and moves the cell

a superfamily of ATP-dependent motor proteins that move toward the plus end of microtubules using intrinsic ATPase activity

a motor protein ATPase that carries out retrograde minus-end movement along microtubules in the cytoplasm; responsible for movement as axonemal dynein in cilia and flagella

movement of vesicles away from the plasma membrane

a complex that serves as the primary microtubule organizing centre of animal cells; composed of two centrioles arranged at right angles to each other

the microtubule-based cytoskeletal structure that forms the core of a cilium or flagellum arranged as nine outer microtubule doublets and one inner doublet

a pair of fused microtubules (one complete/one incomplete) in the axonemes of eukaryotic cilia and flagella

an incomplete microtubule that is connected to the A tubule in an axoneme of a eukaryotic flagellum or cilium

a structure containing microtubules that develops from centrioles from which axonemes of cilia and flagella develop

a structure consisting of nine sets of triplet microtubules embedded in the centrosome of animal cells

a protein that connects adjacent outer double microtubules in the axonemes of eukaryotic cilia and flagella

a multi-unit protein structure known to play a role in the mechanical movement of the eukaryotic flagellum/cilium

a complex of proteins that connects cytoplasmic dynein to its cargo

the contractile bundles in nonmuscle cells are similar to skeletal muscle fibres, but they are smaller (~0.4 µm in fibroblasts), less organized, and they contain different accessory proteins

an actomyosin contractile ring that is a prominent structure during cytokinesis; forms perpendicular to the axis of the spindle apparatus towards the end of telophase