1.1 Cell Theory, Basic Properties of Cells & Origin of Eukaryotic Cells

Types of Microorganisms

Life takes many forms, from giant redwood trees towering hundreds of feet in the air to the tiniest known microbes, which measure only a few billionths of a meter. Humans have long pondered life’s origins and debated the defining characteristics of life, but our understanding of these concepts has changed radically since the invention of the microscope. In the 17th century, observations of microscopic life led to the development of the cell theory: the idea that the fundamental unit of life is the cell, that all organisms contain at least one cell, and that cells only come from other cells.

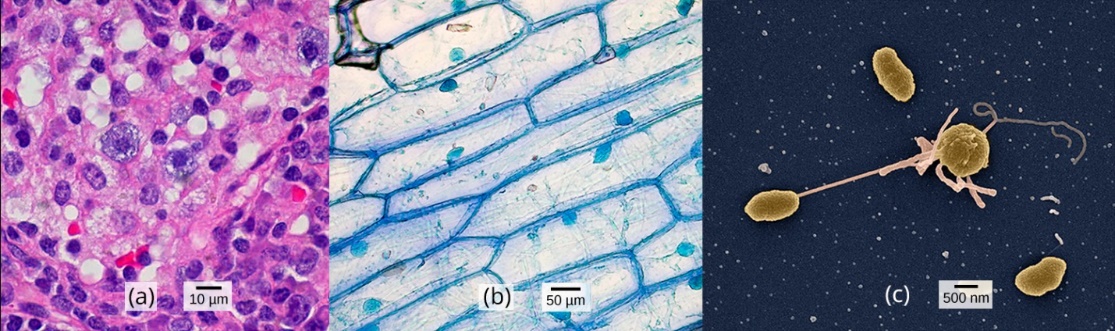

Despite sharing certain characteristics, cells may vary significantly. The two main types of cells are prokaryotic (lacking a nucleus) and eukaryotic (containing a well-organized, membrane-bound nucleus). Each type of cell exhibits remarkable variety in structure, function, and metabolic activity (Figure 1). Unit 1 will focus on the historical discoveries that have shaped our current understanding of cells, including their origins.

| Unit 1, Topic 1—To Do List | Suggested Average Time to Complete (min) |

|---|---|

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Foundations of Modern Cell Theory. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Cell Theory. | 17 |

| Complete Learning Activity: How Science Builds. | 20 |

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Basic Properties of Cells. | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activities: Parts of a Cell; Cell Comparisons; Cell Structure and Function. | 30 |

| Read, make summary notes, and complete the self-check questions for Origin of Eukaryotic Cells. Pay particular attention to the Case Study “What does “slug power” have to do with the origins of Chloroplasts?” | 20 |

| Complete Learning Activity: Endosymbiotic Theory. | 10 |

| ✮ Complete Learning Activity: Endosymbiotic Theory Online Interactive. Note that this activity is included as an option in the Unit 1 Assignment. | 30 |

Foundations of Modern Cell Theory

Section Learning Objectives

By the end of Unit 1, Topic 1, you will be able to:

- Explain what made the discovery of cells possible.

- Explain the key points of cell theory and the individual contributions of Hooke, Schleiden, Schwann, Remak, and Virchow.

- Explain how science builds.

Discovery of Cells

In this section, you will read about experiments that revealed secrets of cell and molecular biology, many of which earned their researchers Nobel and other prizes. But let’s begin here with a Tale of Roberts, two among many giants of science in the Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment, whose seminal studies came too early to win a Nobel Prize.

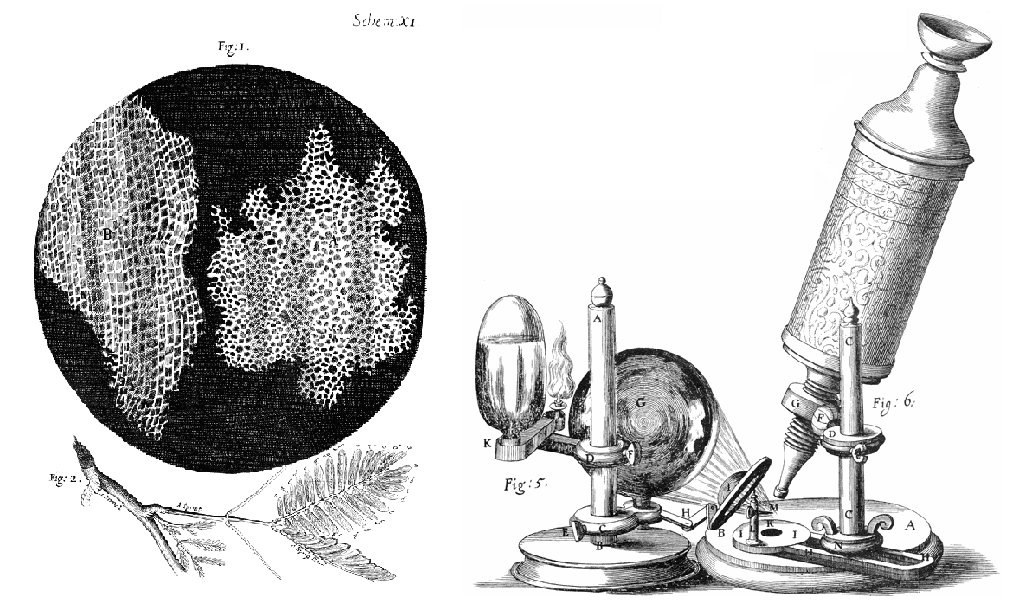

The English scientist Robert Hooke first used the term “cells” in 1665 to describe the small chambers within cork that he observed under a microscope of his own design (Figure 2). Hooke was one of the earliest scientists to study living things under a microscope (investigate Hooke’s drawings and microscope). The microscopes of Hooke’s day were not very strong and magnified images by 30x. However, Hooke was still able to make an important discovery. When he looked at a thin slice of cork under his microscope, he was surprised to see what looked like a honeycomb. To Hooke, thin sections of cork resembled “Honey-comb,” or “small boxes or bladders of air.” He noted that each “Cavern, Bubble, or Cell” was distinct from the others (Figure 2).

Soon after Robert Hooke discovered cells in cork, a Dutch tailor, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), made other important discoveries after improving his own microscope. As a tailor, van Leeuwenhoek used lenses to examine cloth, and it was probably this incentive that led to his interest in lens making. His microscope was more powerful than other microscopes of his day (magnifying images by 270x), and it was almost as strong as modern light microscopes, even though it had a single lens. Using his microscope, Leeuwenhoek discovered tiny living animals, such as rotifers. Leeuwenhoek also discovered human blood cells. He even scraped plaque from his own teeth and observed it under the microscope!

Self-Check

- What type of material is cork? Do you know where cork comes from?

Show/Hide answer.

It’s from tree bark. At the time, Hooke was unaware that the cork cells were long dead and therefore, lacked the internal structures found within living cells.

- What do you think Leeuwenhoek saw in the plaque? He saw tiny living things with a single cell that he named animalcules (“tiny animals”).

Show/Hide answer.

Bacteria. Today, we call Leeuwenhoek’s animalcules bacteria.

Source: 2.2 Foundations of Modern Cell Theory (Bruslind/OpenStax)

Cell Theory

As described above, the discovery of the cell was made possible by the invention of the microscope. The microscopes we use today are far more complex than those used in the 1600s by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Later advances in lenses, microscope construction, and staining techniques enabled other scientists to see some components inside cells. Despite Hooke’s and van Leeuwenhoek’s early description of cells, their significance as the fundamental unit of life was not yet recognised until nearly 200 years later.

At this time, the German botanist Matthias Jakob Schleiden (1804–1881) was the first to recognise that all plants, and all the different parts of plants, are composed of cells. Visualizing plant cells was relatively easy because plant cells are clearly separated by their thick cell walls. Schleiden believed that cells formed through crystallization, rather than cell division. While having dinner with zoologist Theodor Schwann (1810–1882), Schleiden mentioned his idea. Schwann, who came to similar conclusions while studying animal tissues, quickly saw the implications of their work. In 1839, he published “Microscopic Investigations on the Accordance in the Structure and Growth of Plants and Animals,” which included the first and second statements of the cell theory: “All living things are made up of one or more cells,” and “the cell is the structural unit of life.”

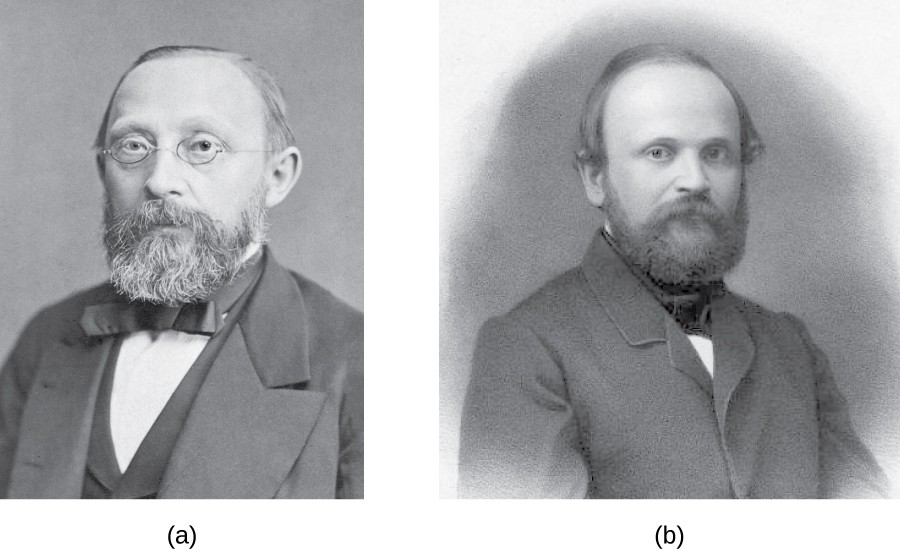

In the 1850s, two Polish scientists living in Germany pushed this idea further, culminating in what we recognise today as the modern cell theory. In 1852, Robert Remak (1815–1865), a prominent neurologist and embryologist, published convincing evidence that cells are derived from other cells as a result of cell division. Based on this realization, Virchow extended the work of Schleiden and Schwann by proposing that living cells arise only from other living cells. However, this idea was questioned by many in the scientific community because most people, scientists included, believed that nonliving matter could spontaneously generate living tissue. Three years later, Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), a well- respected pathologist, published an editorial essay entitled “Cellular Pathology,” which popularized the concept of cell theory using the Latin phrase omnis cellula a cellula (“all cells arise from cells”), which is essentially the third tenet of modern cell theory (3). Given the similarity of Virchow’s work to Remak’s, there is some controversy about which scientist should receive credit for articulating cell theory. See the following Science and Plagiarism feature below for more about this controversy.

The expanded version of the cell theory can also include the following (4):

- Cells carry genetic material passed to daughter cells during cellular division.

- All cells are essentially the same in chemical composition.

- Energy flow (metabolism and biochemistry) occurs within cells.

Eye on Ethics: Science and Plagiarism

Rudolf Virchow, a prominent, Polish-born, German scientist, is often remembered as the “Father of Pathology.” Well known for innovative approaches, he was one of the first to determine the causes of various diseases by examining their effects on tissues and organs. He was also among the first to use animals in his research and, as a result of his work, he was the first to name numerous diseases and created many other medical terms. Over the course of his career, he published more than 2,000 papers and headed various important medical facilities, including the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, a prominent Berlin hospital and medical school. But he is, perhaps, best remembered for his 1855 editorial essay titled “Cellular Pathology,” published in Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie, a journal that Virchow himself cofounded and still exists today. Despite his significant scientific legacy, there is some controversy regarding this essay, in which Virchow proposed the central tenet of modern cell theory—that all cells arise from other cells. Robert Remak, a former colleague who worked in the same laboratory as Virchow at the University of Berlin, had published the same idea three years before. Though it appears Virchow was familiar with Remak’s work, he neglected to credit Remak’s ideas in his essay. When Remak wrote a letter to Virchow pointing out similarities between Virchow’s ideas and his own, Virchow was dismissive. In 1858, in the preface to one of his books, Virchow wrote that his 1855 publication was just an editorial piece, not a scientific paper, and thus there was no need to cite Remak’s work. By today’s standards, Virchow’s editorial piece would certainly be considered an act of plagiarism, since he presented Remak’s ideas as his own. However, in the 19th century, standards for academic integrity were much less clear. Virchow’s strong reputation, coupled with the fact that Remak was a Jew in a somewhat antiSemitic political climate, shielded him from any significant repercussions. Today, the process of peer review and the ease of access to the scientific literature help discourage plagiarism. Although scientists are still motivated to publish original ideas that advance scientific knowledge, those who would consider plagiarizing are well aware of the serious consequences. In academia, plagiarism represents the theft of both individual thought and research—an offense that can destroy reputations and end careers.

Despite that we are told repeatedly in school to conduct ourselves with academic integrity, professional researchers do not always behave this way. Retraction Watch is a blog about scientific publications that had been suspected of a lack of integrity, such as fabricated data, and have been retracted. The lack of integrity not only damages the reputation of the scientists who had their papers retracted but also harms other researchers. It may take years for a retraction to be decided and publicized. By the time a paper is retracted, other researchers may already have spent large amounts of money and time in pursuing a topic that had been falsified. Worse yet are the fraudulent papers that have not yet been identified because people may unknowingly use the false information in subsequent papers and hence propagate information that is actually wrong. Therefore, it is important for everyone to produce work with integrity, to protect oneself and others.

The panels below (Figure 3) show (a) Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902) popularized the cell theory in an 1855 essay entitled “Cellular Pathology.” and (b) Robert Remak (1815–1865) who first published the idea that all cells originate from other cells in 1852 and who was a contemporary and former colleague of Virchow (Kisch 1954; Harris 2000; Webster 1981; Zuchora-Walske 2015).

Learning Activity: Cell Theory

- Visit the following sites to learn more about van Leeuwenhoek’s contributions to the Cell Theory. The videos will provide you with a visualization of van Leeuwenhoek’s important contributions to the Cell Theory. After you view the videos, attempt the following questions to test your ability to recall important contributors and tools in developing the Cell Theory.

- “Lens making in the 1600s” (4:16 min) by Corning Museum of Glass (2016).

- “Leeuwenhoek’s microscope” (5:47 min) by LabXchange (2021).

- Text background by University of California Museum of Paleontology ([date unknown]).

Answer the following questions pertaining to the videos and text reading:

- Which statement(s) is(are) true about van Leeuwenhoek’s lens making activities in the 1600s?

- He melted plastic over a flame and polished it with sandpaper.

- He ground and polished tiny pieces of glass and fine powder that were glued onto a stick.

- He also used a secret method of glass blowing a thin-walled glass tube over a flame.

- His surviving lenses are double convex, ground and polished on both sides.

Show/Hide answer.

b, c and d

- Who proposed that plant embryos arose from a single cell?

- Matthias Schleiden

- Theodor Schwann

- Robert Hooke

- Louis Pasteur

Show/Hide answer.

a. Matthias Schleiden

- Which microscope was used by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek?

- Single-lens

- Confocal microscope

- Double-lens

- Compound microscope

Show/Hide answer.

a. Single-lens

- Which of the following individuals did not contribute to the establishment of cell theory?

- Girolamo Fracastoro

- Matthias Schleiden

- Robert Remak

- Robert Hooke

Show/Hide answer.

a. Girolamo Fracastoro did not contribute to the establishment of cell theory.

Learning Activity: How Science Builds: Scientific Discovery Isn’t as Simple as One Good Experiment

This activity illuminates the twists and turns that came together to build the foundations of Cell Biology.

- Read (or re-read) the ‘Eye on Ethics: Science and Plagiarism’ excerpt.

- Watch the video Cell theory | Structure of a cell | Biology | Khan Academy (8:00 min) by Khan Academy (2015).

- Watch the video “The weird and wonderful history of cell theory” (6:00 min) by Lauren Royal-Woods at TEDEd (2012).

- Answer the following questions:

- Can you describe how science builds using examples provided about the development of specific aspects of the cell theory in these videos?

- Why do you think it was so difficult to develop the cell theory?

Basic Properties of Cells

Section Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the structural and functional aspects that are common to all cells, from organisms as different as bacteria and human beings.

- Describe how cells that are structurally diverse perform the same functions.

- Identify and describe structures and organelles unique to eukaryotic cells.

- Compare and contrast similar structures found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

Introduction

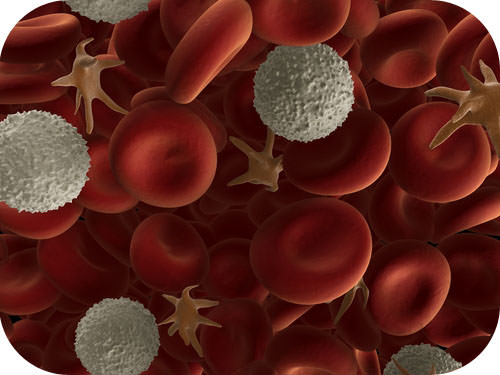

What is the same between a bacterial cell and one of your cells? The cell theory states that the cell is the fundamental unit of life. As the image of human blood in Figure 4 shows, cells come in different shapes and sizes even within one tissue, such as blood. The shapes and sizes directly influence the function of the cell. Yet, all cells—from cells in the smallest bacteria to those in the largest whale—perform some similar functions, so they do have parts in common. How did all known organisms come to have such similar structural parts and functions? The similarities show that all life on Earth has a common evolutionary history as will be discussed soon.

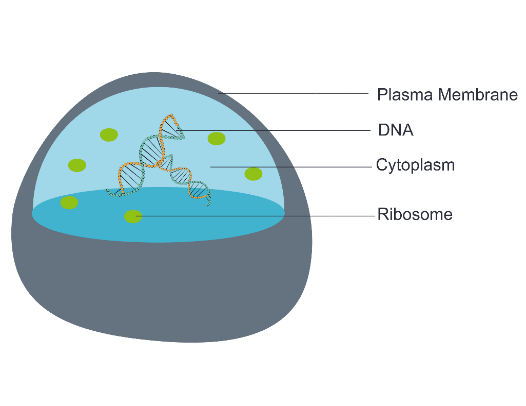

All cells (bacterial, archaeal, eukaryotic) share the following four common structural and functional components (Figure 5):

-

- The plasma membrane (a type of cell membrane) is a thin coat of lipids and proteins that surrounds a cell. It forms the physical boundary between the cell and its environment. You can think of it as the “skin” of the cell.

- Cytoplasm refers to all of the cellular material inside of the plasma membrane. Cytoplasm is made up of a jelly-like substance called cytosol, and it contains other cell structures, such as ribosomes. Cytoskeletal filaments made of proteins, including actin and tubulin, are found in the cytosol of most cells.

- Ribosomes are the structures in the cytoplasm in which proteins are made. Although all ribosomes are composed of both RNA and protein, there are some distinct differences between those found in bacteria/archaea and those found in eukaryotes, particularly in terms of size and location.

- DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) is the genetic material of the cell, the instructions for the cell’s abilities and characteristics. DNA is a nucleic acid found in most cells. It contains the genetic instructions that cells need to make RNA and proteins. A complete set of genes, referred to as a genome, is localized in an irregularly shaped region known as the nucleoid in bacterial and archaeal cells, but it is enclosed in a membrane-bound nucleus in eukaryotic cells. An exception is mature erythrocytes (red blood cells) that do not contain a nucleus to give more room for hemoglobin.

In addition to the common structural components listed above, all living cells have the common characteristics listed below. As you progress through this course, each of these characteristics will be considered at different levels and in different contexts.

Complexity and organization — Each cell type has a consistent structure and composition of macromolecules to maximize its specialized function

- Thermal energy from the environment causes many molecules to exhibit a random motion that is used in subsequent highly organized and directed events.

Metabolism — the web of all enzyme-catalyzed reactions in a cell or organism

- Enzymes increase the rate of chemical reactions that are required for cells to maintain the characteristics of life.

- Metabolism is required to convert food into energy for cellular processes, to convert food/fuel into macromolecules and to eliminate wastes.

Energy — the living cells of every organism constantly acquire and use energy

- Just as living things must continually consume or manufacture food to replenish their energy supplies, cells must continually produce more energy to replenish that used by the many energy-requiring chemical reactions that constantly take place.

- All cells use adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) as their source of intracellular chemical energy.

- All cells carry out glycolysis to convert the energy in organic molecules into ATP.

- All cells use a membrane system to manufacture ATP.

Response to stimuli — living cells can respond to and interact with their environment

- The response of a single-celled organism like an amoeba is obvious as it moves toward nutrients in its immediate vicinity or away from an object in its path.

- In multi-cellular organisms, cells possess membrane receptors that mediate specific responses to soluble substances in their environment or present in the membranes of other cells. The responding cell may change its metabolic activity, move to another location or even commit suicide.

Mechanical activity — cells are involved in numerous mechanical activities

- Cells assemble and disassemble structures.

- Cells transport substances and organelles around, often with the help of motor proteins.

Self regulation — cells carry out a series of ordered reactions that are self-adjusted to maintain a complex, highly ordered state

- Cells use backup mechanisms to monitor and correct processes such as division, growth and differentiation.

Genetic program — cells contain molecules of DNA and a genetic code to use it

- Cells are built from and function based on information supplied in the form of genes, which are made of DNA.

- Genes supply the information to direct the formation of cellular structures, for running cellular activities, for making more of themselves and for facilitating evolution.

Reproduction — living cells give rise to other cells either sexually or asexually

- A mother cell divides into two daughter cells that contain an equal share of genetic information.

- The daughter cells do not always have an equal volume.

Cell evolution — all cells arose from a single, common ancestor present three billion years ago

- Evidence exists from the presence of common structures in all living cells, including a common genetic code, a cytoplasm, a plasma membrane and ribosomes.

- Cells continue to evolve as evidenced by the evolution of bacterial drug resistance.

Two Main Types of Cells

The evolution of life on Earth over the past 4 billion years has resulted in a huge variety of species. For more than 2,000 years, humans have been trying to classify the great diversity of life. The science of classifying organisms is called taxonomy. Classification is an important step in understanding the present diversity and past evolutionary history of life on Earth. All modern classification systems have their roots in the Linnaean classification system. It was developed by Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus in the 1700s. The Linnaean system of classification consists of a hierarchy of groupings, called taxa (singular, taxon). Taxa range from the kingdom to the species. The kingdom is the largest and most inclusive grouping. It consists of organisms that share just a few basic similarities. Examples are the plant and animal kingdoms. The species is the smallest and most exclusive grouping. It consists of organisms that are similar enough to produce fertile offspring together. Closely related species are grouped together in a genus.

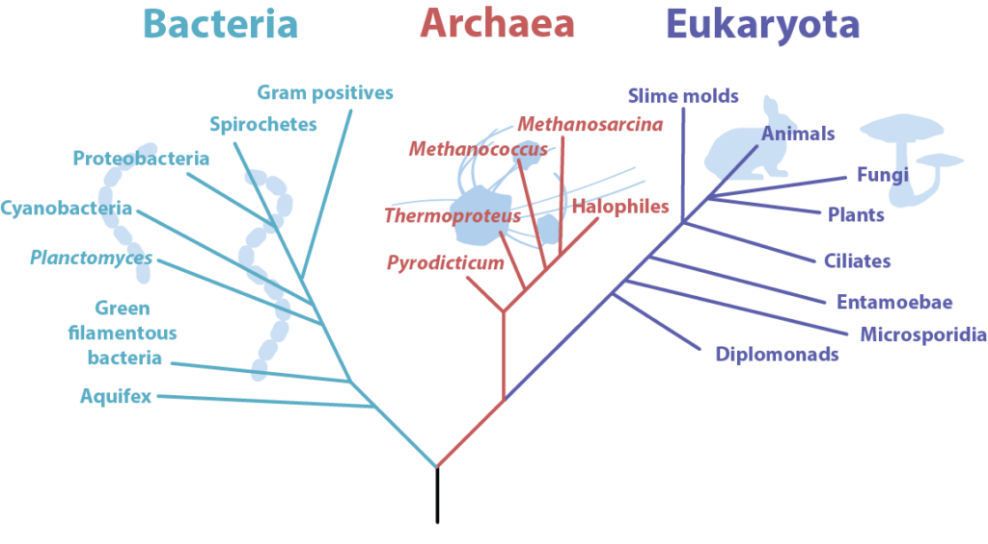

A major change to the Linnaean system was the addition of a new taxon called the domain. A domain is a taxon that is larger and more inclusive than the kingdom. Most biologists agree there are three domains of life on Earth: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota (Figure 6). Both Bacteria and Archaea consist of single-celled prokaryotes. Eukaryota consists of all eukaryotes, from single-celled protists to humans. This domain includes the Animalia (animals), Plantae (plants), Fungi (fungi), and Protista (protists) kingdoms (Figure 6).

General Comparison of Cell Structures — Prokaryotes

Although all cells share the four common structural and functional components as described above, prokaryotes differ from eukaryotic cells in several ways. The crux of their key difference can be deduced from their names: “karyose” is a Greek word meaning “nut” or “centre,” a reference to the nucleus of a cell. “Pro” means “before,” while “eu” means “true,” indicating that prokaryotes lack a nucleus (“before a nucleus”) while eukaryotes have a true nucleus.

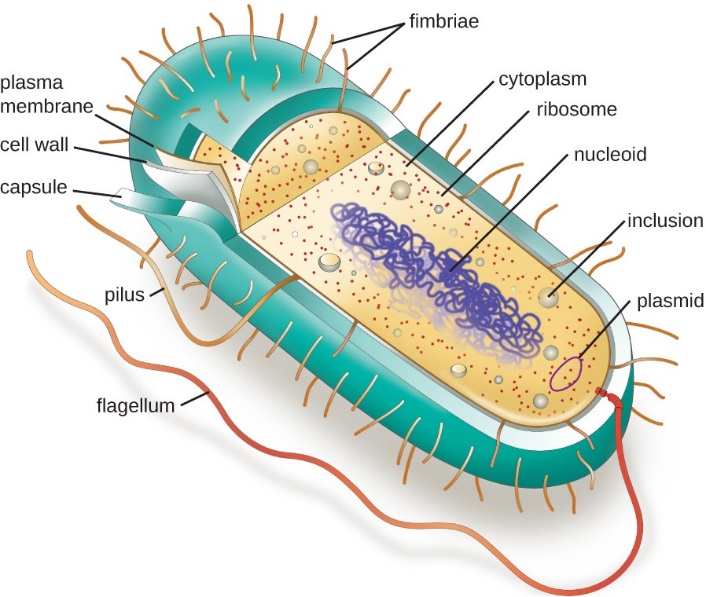

The structures inside a cell are analogous to the organs inside a human body, with unique structures suited to specific functions. Some of the structures found in prokaryotic cells are similar to those found in some eukaryotic cells; others are unique to prokaryotes. Although there are some exceptions, eukaryotic cells tend to be larger than prokaryotic cells. The larger size of eukaryotic cells dictates the need to compartmentalize various chemical processes within different areas of the cell, using complex membrane-bound organelles. In contrast, prokaryotic cells generally lack membrane-bound organelles; however, they often contain inclusions and microcompartments that compartmentalize their cytoplasm. The structures typically associated with prokaryotic cells are illustrated in Figure 7 and summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1: Prokaryotic Cell Structures. (Wakim and Grewal/Human Biology/LibreTexts) CK-12 License |

|

| Cell Structure | Description |

| Pili | Small projections outside of the cell; aid in attachment and reproduction |

| Flagellum | Long projection(s) outside of the cell in some bacteria; aids in the motility |

| Capsule | A thick protective layer outside the cell wall of some bacteria |

| Cell wall | Outer layer of bacterial cells; more chemically complex than eukaryotic cell walls |

| Plasma membrane | Phospholipid bilayer marking the outside of the cytoplasm |

| Cytoplasm | The fluid portion of the cell |

| Ribosome | Involved in protein synthesis |

| Nucleoid | Circular DNA found in the cytoplasm |

| Plasmid | Small loops of DNA found in some bacteria |

More recently, microbiologists are resisting the term prokaryote because it lumps both bacteria and the subsequently discovered archaea in the same category. Both cells are prokaryotic because they lack a nucleus and other organelles (such as mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, etc.), but they aren’t closely related genetically. Therefore, to honour these differences we will refer to the groups as the archaea, the bacteria, and the eukaryotes.

Self-Check

True or False: All prokaryotes possess flagella, pili, fimbriae, and capsules.

Show/Hide answer

False

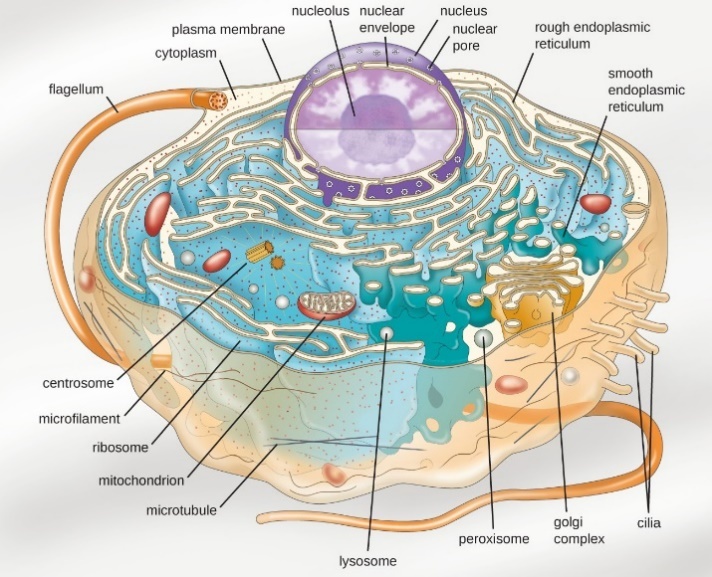

Eukaryotes

Eukaryotic organisms include protozoans, algae, fungi, plants, and animals. Some eukaryotic cells are independent, single-celled microorganisms, whereas others are part of multicellular organisms. The cells of eukaryotic organisms have several distinguishing characteristics. Above all, eukaryotic cells are defined by the presence of a nucleus surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane. Also, eukaryotic cells are characterized by the presence of membrane-bound organelles in the cytoplasm. The word “organelle” means “little organ,” each of which has specialized cellular functions, just as your body’s organs have specialized functions.

Organelles such as mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes are held in place by the cytoskeleton, an internal network that supports transport of intracellular components and helps maintain cell shape (Figure 8). The genome of eukaryotic cells is packaged in multiple, rod-shaped chromosomes as opposed to the single, circular-shaped chromosome that characterizes most prokaryotic cells.

Have you ever heard the phrase “form follows function?” It’s a philosophy that many industries follow. In architecture, this means buildings should be constructed to support the activities that will be carried out inside them. For example, a skyscraper should include several elevator banks, and a hospital should have its emergency room easily accessible.

Our natural world also uses the principle of form follows function, especially in cell biology, and this will become clear as we explore the structure and function of eukaryotic cells. Table 2 compares the characteristics of eukaryotic cell structures with those of bacteria and archaea.

| Table 2: Comparing Cell Structures in Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryotes. (Adapted from Parker et al. 2016/ Microbiology/ OpenStax) CC BY 4.0 |

|||

| Cell Structure | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes | |

| Bacteria | Archaea | ||

| Size | ~0.5–1 μm | ~0.5–1 μm | ~5–20 μm |

| Surface area-to-volume ratio | High | High | Low |

| Nucleus | No | No | Yes |

| Genome characteristics | · Single chromosome · Circular · Haploid · Lacks histones |

· Single chromosome · Circular · Haploid · Contains histones |

· Multiple chromosomes · Linear · Haploid or diploid · Contains histones |

| Cell division | Binary fission | Binary fission | · Mitosis · Meiosis |

| Membrane lipid composition | · Ester-linked straight-chain fatty acids · Bilayer |

· Ether-linked branched isoprenoids · Monolayer or bilayer |

· Ester-linked straight-chain fatty acids · Cholesterol, sterols · Bilayer |

| Cell wall composition | · Peptidoglycan · None |

· Pseudopeptidoglycan · Glycopeptide · Polysaccharide · Protein (S-layer) · None |

· Cellulose (plants, some algae) · Chitin (molluscs, insects, crustaceans, fungi) · Silica (some algae) · Most others lack cell walls |

| Motility structures | Rigid spiral flagella composed of flagellin | Rigid spiral flagella composed of archaeal flagellins | Flexible flagella and cilia composed of microtubules |

| Membrane-bound organelles | No | No | Yes |

| Endomembrane system | No | No | Yes (ER, Golgi, lysosomes) |

| Ribosomes | 70S | 70S | · 80S (cytoplasm, rough ER) · 70S (mitochondria, chloroplasts) |

Cell Morphology

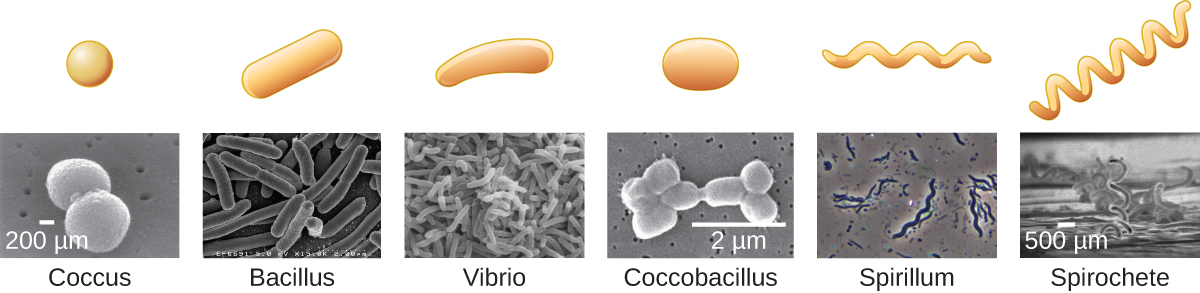

Individual cells of a particular prokaryotic organism are typically similar in shape, or cell morphology. The shape dictates how that cell will grow, reproduce, obtain nutrients, move, and it’s important to the cell to maintain that shape to function properly. Cell morphology can be used as a characteristic to assist in identifying particular microbes, but it’s important to note that cells with the same morphology are not necessarily related. Although thousands of prokaryotic organisms have been identified, only a handful of cell morphologies are commonly seen microscopically. Figure 9 names and illustrates cell morphologies commonly found in prokaryotic cells.

There are additional shapes seen for bacteria, and an even wider array for the archaea, which have even been found as star or square shapes. Eukaryotic microbes also tend to exhibit a wide array of shapes, particularly the ones that lack a cell wall such as the protozoa.

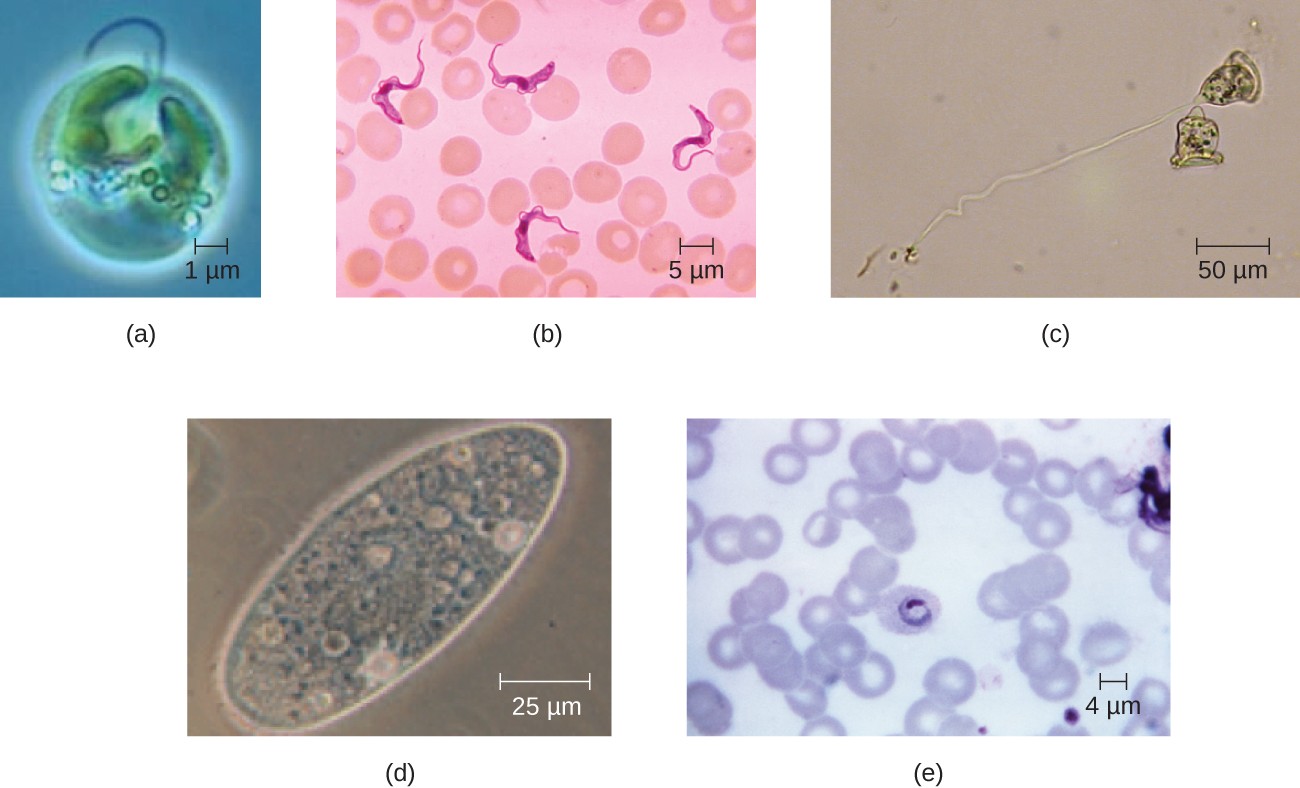

Eukaryotic cells also display a wide variety of different cell morphologies. Possible shapes include spheroid, ovoid, cuboidal, cylindrical, flat, lenticular, fusiform, discoidal, crescent, ring stellate, and polygonal (Figure 10). Some eukaryotic cells are irregular in shape, and some are capable of changing shape. The shape of a particular type of eukaryotic cell may be influenced by factors such as its primary function, the organization of its cytoskeleton, the viscosity of its cytoplasm, the rigidity of its cell membrane or cell wall (if it has one), and the physical pressure exerted on it by the surrounding environment and/or adjoining cells.

Ribosomes

All cellular life synthesizes proteins, and organisms in all three domains of life possess ribosomes, structures responsible for protein synthesis. However, ribosomes in each of the three domains are structurally different. Ribosomes are evolutionarily conserved protein synthesizing machines found in all cells (see Table 2). Because protein synthesis is essential for all cells, ribosomes are found in practically every cell, although they are smaller in prokaryotic cells. Ribosomes are particularly abundant in immature red blood cells for the synthesis of hemoglobin, which functions in the transport of oxygen throughout the body.

Ribosomes consist of a large and a small subunit, each made up of multiple proteins and one or more molecules of ribos